Flint water crisis

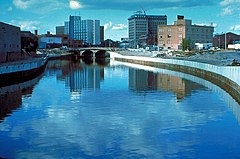

Flint River in Downtown Flint ca. 1979 | |

| Time | April 2014 – present |

|---|---|

| Duration | Ongoing |

| Location | Flint, Michigan, United States |

| Coordinates | 43°0′36″N 83°41′24″W / 43.01000°N 83.69000°W |

| Type | Lead contamination crisis Possible Legionnaires' disease outbreak |

| Outcome | Public health state of emergency Five lawsuits Several investigations Resignation of four government officials |

| Non-fatal injuries | Between 6,000–12,000 [1] |

The Flint water crisis is an ongoing drinking water contamination crisis in Flint, Michigan, in the United States.

After the change in water source from Detroit to the Flint River, the city's drinking water had a series of issues that culminated with lead contamination, creating a serious public health danger. The corrosive Flint River water caused lead from aging pipes to leach into the water supply, causing extremely elevated levels of lead. As a result, between 6,000 and 12,000 residents had severely high levels of lead in the blood and experienced a range of serious health problems.[1] The water change is also a possible cause of an outbreak of Legionnaires' disease in the county that has killed 10 people and affected another 77.[2]

On November 13, 2015, four families filed a federal class action lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan in Detroit against Governor Rick Snyder and thirteen other city and state officials, and three separate people filed a similar suit in state court two months later, and three more lawsuits were filed after that. Separately, the United States Attorney's Office for the Eastern District of Michigan and the Michigan Attorney General's office opened investigations. On January 5, 2016, the city was declared to be in a state of emergency by the Governor of Michigan, before President Obama declared the crisis as a federal state of emergency,[3] authorizing additional help from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Department of Homeland Security less than two weeks later.

Four government officials—one from the City of Flint, two from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, and one from the Environmental Protection Agency—resigned over the mishandling of the crisis, and Snyder issued an apology to citizens, while promising money to Flint for medical care and infrastructure upgrades.

History of Flint water supply

Before 2014

Flint built its first water treatment plant (now defunct) in 1917. The city built a second plant in 1952.

In 1962, Flint had plans to build a pipeline from Lake Huron to Flint, but a real estate profiteering scandal caused the city commission to abandon the pipeline project in 1964 and instead buy water from the city of Detroit.[4]

In 1967, the city stopped treating its own water when the pipeline from Detroit was completed.[5][6]

At the time of Flint's population peak and economic height (when the city was the center of the automobile industry), Flint's plants pumped 100 million gallons (380,000 m3) of water per day. With the decline of the city's industry and a significant drop in the city's population (from almost 200,000 in 1960 to about 99,000 today), Flint pumped less water. By October 2014, when the Flint plant ended operations, it pumped just 16 million gallons (61,000 m3) daily.[5]

In March 2013, the Flint city council voted to switch their water supply from the Detroit Water and Sewer Department (DWSD) to the new $233 million Lake Huron-sourced Karegnondi Water Authority (KWA).[7] The switch was also approved by the Flint emergency manager.[8] DWSD strongly opposed Flint being allowed to join KWA and released a document accusing Flint of starting a 'water war' and asked the state to block Flint's participation in KWA.[9] State Treasurer, Andy Dillon, approved Flint joining KWA but gave DWSD the opportunity to make a final offer to convince Flint to stay on Detroit water.[10] Flint declined the final DWSD offer. Immediately after Flint declined the offer, DWSD gave Flint notice that their long-standing water agreement would terminate in twelve months.[11] This meant that Flint's water agreement with Detroit would end in April 2014 but construction of KWA was not expected to be completed until the end of 2016. Therefore, in April 2014 (when the water agreement terminated), Flint switched their water supply from DWSD to Flint's backup supply, the Flint River. The Flint river was expected to supply potable water until KWA construction was completed in 2016. Given that DWSD strongly opposed Flint joining KWA and that Flint provided 6% ($22 million) of DWSD revenue, it is not clear why DWSD terminated the agreement in 2013 as they could have received revenue for at least two additional years and they did not have a buyer waiting to take over the Flint water.[12]

Switch in source in 2014

Starting in 2010, Genesee County had spearheaded the development of the Karegnondi Water Authority (KWA) to supply it and Lapeer and Sanilac counties—plus the cities of Lapeer and Flint—with water.[13] On March 25, 2013, Flint City Council approved 7-1 to purchase 16 million gallons per day from the KWA rather than go with Flint River water as a permanent supply.[14] Flint emergency manager (EM) Ed Kurtz and Mayor Dayne Walling approved the action on March 29 and forward the action for the State Treasurer to approve.[15]

The Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD), on April 1, sent out a press release demanding the state should block Flint's request as it would hurt Detroit Water and start a water war and said that "any claim that it would save the cash-strapped city money is specious".[12] The release also put out several options for Flint, including sale of raw untreated water. Genesee County Drain commissioner Wright, after accusing the DWSD of negotiating through the media, replied, "It would be unprecedented for the state to force one community to enter into an agreement with another, simply to artificially help one community at the other's expense. This is exactly what the (Detroit Water and Sewerage Department) is arguing should be done."[16]

Still, on April 15, State Treasurer Andy Dillon gave approval to Kurtz to enter into a water purchase contracts with the KWA.[17] EM Kurtz signed the KWA water purchase agreement on April 16.[18] On April 17, the Detroit Water and Sewer Department gave its one-year termination notice to the city just days after the County and City rejected the DWSD' last offer. The DWSD also expected that Flint pay them for past investments in the water system that benefited regional customers; Flint and Genesee County rejected such responsibility, although they indicated willingness to purchase some pipeline. Governor Rick Snyder called a meeting of the three parties for April 19 to discuss those and other issue related to the KWA project.[17]

In late April 2014, in an effort to save about $5 million over less than two years,[18][19][20] the city switched from purchasing treated Lake Huron water from Detroit, as it had done for 50 years, to treating water from the Flint River. The plan was to attach to the Karegnondi system, which was under construction, and would be completed almost three years later. The Flint River had been the designated backup water source for years.[21][22] By December 2014, the city had invested $4 million into its water plant.[23]

Return to Detroit water

In October 2015, the water supply was switched back to Detroit.[24][25] Flint started adding additional orthophosphate, a corrosion inhibitor, to the Detroit water in December 2015 to counteract the corrosion in the pipes caused by the Flint River water.[26]

On October 8, Snyder asked the Michigan Legislature to contribute $6 million of the $12 million in costs for Flint to return to Lake Huron water (from the newly created Great Lakes Water Authority), with the City of Flint paying $2 million and the Flint-based Charles Stewart Mott Foundation paying $4 million.[27][28] State Senator Jim Ananich, who represents Flint, called for the state to refund the $2 million to the city; Ananich also requested further emergency funding from the state and a commitment to long-term funding to address the effects of the lead contamination.[29]

Future

Flint still has plans to join the Karegnondi Water Authority after a pipeline from Lake Huron to Flint is completed in June 2016.[30]

Studies

Lead exposure

In January 2015, a public meeting was held, where citizens complained about the "bad water."[31] Residents complained about the taste, smell and appearance of the water for 18 months before a Flint physician found highly elevated blood lead levels in the children of Flint while the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality insisted the water was safe to drink.[32] It was determined that the river water, which is more corrosive than the lake water, was leaching lead from aging pipes.[33]

While the local outcry about Flint water quality was growing in early 2015, Flint water officials filed papers with state regulators purporting to show that "tests at Flint's water treatment plant had detected no lead and testing in homes had registered lead at acceptable levels."[34] The documents falsely claim that the city had tested tap water from homes with lead service lines, and therefore the highest lead-poisoning risks; in reality; the city does not know the locations of lead service lines, which city officials acknowledged in November 2015 after the Flint Journal/MLive published an article revealing the practice after obtaining documents through the Michigan Freedom of Information Act.[35] The Journal/MLive reported that the city had "disregarded federal rules requiring it to seek out homes with lead plumbing for testing, potentially leading the city and state to underestimate for months the extent of toxic lead leaching into Flint's tap water."[35] Only after independent research was conducted by Marc Edwards and a local physician, Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, was a public-health emergency declared.[34][35]

In August 2015, three organizations, citing lead levels and other problems, "delivered more than 26,000 online petition signatures to Mayor Dayne Walling, demanding the city end its use of the Flint River and reconnect the city to the Detroit water system."[33]

In September 2015, a team working under Edwards, an engineering professor at Virginia Tech and an expert on municipal water quality who had been sent to study the water supply under a National Science Foundation grant, published a report finding that Flint water was "very corrosive" and "causing lead contamination in homes" and concluding that "Flint River water leaches more lead from plumbing than does Detroit water. This is creating a public health threat in some Flint homes that have lead pipe or lead solder."[33][36][37] Edwards was shocked by the extent of the contamination and by authorities' inaction in the face of their knowledge of the contamination.[37] Volunteer teams led by Edwards found that at least a quarter of Flint households have levels of lead above the federal level of 15 parts per billion (ppb) and that in some homes, lead levels were at 13,200 ppb.[37] Edwards said: "It was the injustice of it all and that the very agencies that are paid to protect these residents from lead in water, knew or should've known after June at the very very latest of this year, that federal law was not being followed in Flint, and that these children and residents were not being protected. And the extent to which they went to cover this up exposes a new level of arrogance and uncaring that I have never encountered."[37]

Research done after the switch to the Flint River source found that the proportion of children with elevated blood-lead levels (above five micrograms per deciliter, or 5 × 10–6 grams per 100 milliliters of blood) rose from 2.1% to 4%, and in some areas to as much as 6.3%.[38]

On September 24, 2015, Hurley Medical Center in Flint released a study, led by Hanna-Attisha, the MPH program director for pediatric residency at the Hurley Children's Hospital, confirming that proportion of infants and children with elevated levels of lead in their blood had nearly doubled since the city switched from the Detroit water system to using the Flint River as its water source.[34][39] Using hospital records, Hanna-Attisha found that a steep rise in blood-lead levels correlated to the city's switch in water sources.[34] The study was initially dismissed by Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) spokesman Wurfel, who "repeated a familiar refrain: Repeated testing indicated the water tested within acceptable levels."[34] Later, Wurfel apologized to Hanna-Attisha.[34]

On January 11, 2016, the Virginia Tech research team led by Edwards announced that it had completed its work.[40] Edwards said "We now feel that Flint's kids are finally on their way to being protected and decisive actions are under way to ameliorate the harm that was done."[41] Edwards credited the Michigan ACLU and the group Water You Fighting For with doing the "critical work of collecting and coordinating" many water samples analyzed by the Virginia Tech team.[41] Although the labor of the team (composed of scientists, investigators, graduate students, and undergraduates) was free, the investigation still spent more than $180,000 for such expenses as water testing and payment of Michigan Freedom of Information Act costs. A GoFundMe campaign has raised almost $3,010 of the $150,000 needed for the team to recover its costs.[40][41]

Possible link to Legionnaires' disease spike

On January 13, 2016, Snyder said 87 cases of Legionnaires' disease, a waterborne disease, were reported in Genesee County from June 2014 – November 2015, resulting in 10 deaths. Although the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) said that there is no evidence of a clear link between the spike in cases and the water system change,[2] Edwards stated the contaminated Flint water could be linked to the spike, telling reporters, "It's very possible that, the conditions in the Flint River water contributed. We've actually predicted earlier this year, that the conditions present in Flint would increase the likelihood of Legionnaires' disease. We wrote a proposal on that to the National Science Foundation that was funded and we visited Flint and did two sampling events. The first one, which was focused on single family homes or smaller businesses. We did not find detectable levels of Legionella bacteria that causes disease, in those buildings. But, during our second trip, we looked at large buildings and we found very high levels of Legionella that tends to cause the disease."[42] In a second report released January 21, state researchers had still not pin-pointed the source of the outbreak. [43]

The Flint Journal obtained documents via the Michigan Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) on the Legionnaires' outbreak and published an article on them on January 16, 2016. The documents indicated that on October 17, 2014, employees of the Genesee County Health Department and the Flint water treatment plant met to discuss the county's "concerns regarding the increase in Legionella cases and possible association with the municipal water system."[44] By early October 2014, the Michigan DEQ were aware of a possible link between the water in Flint and the Legionnaires' outbreak, but the public was never informed, and the agency gave assurances about water safety in public statements and at public forums.[44] An internal January 27, 2015 email from a supervisor at the health department said that the Flint water treatment plant had not responded in months to "multiple written and verbal requests" for information.[44] In January 2015, following the complete breakdown in communication between the city and the county on the Legionnaires' investigation, the county filed a FOIA request with the city, seeking "specific water testing locations and laboratory results ... for coliform, E-coli, Heterotropic Bacteria and trihalomethanes" and other information.[44] In April 2015, the county health department contacted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and in April 2015 a CDC employee wrote in an email that the Legionnaire's outbreak was "very large, one of the largest we know of in the past decade and community-wide, and in our opinion and experience it needs a comprehensive investigation."[44] However, MDHHS told the county health department at the time that federal assistance was not necessary.[44]

Inquiries, investigations, and resignations

One focus of inquiry is when Snyder became aware of the issue, and how much he knew about it.[45] In a July 2015 email, Dennis Muchmore (then Snyder's chief of staff) wrote to a Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) official: "I'm frustrated by the water issue in Flint. I really don't think people are getting the benefit of the doubt. These folks are scared and worried about the health impacts and they are basically getting blown off by us (as a state we're just not sympathizing with their plight)."[45][46] In a separate email sent on July 22, 2015, MDHHS local health services director Mark Miller wrote to colleagues that it "Sounds like the issue is old lead service lines."[46] These emails were obtained under the Michigan Freedom of Information Act by Virginia Tech researchers studying the crisis, and were released to the public in the first week of January 2016.[46]

In October 2015, it was reported that the city government's data on lead water lines in the city was stored on 45,000 index cards (some dating back a century) located in filing cabinets in Flint’s public utility building.[47][48] The Department of Public Works said that it was trying to transition the data into an electronic spreadsheet program, but as of October 1, 2015, only about 25% of the index card information had been digitized.[47]

On October 21, 2015, Snyder announced the creation of a five-member Flint Water Advisory Task Force, consisting of Ken Sikkema of Public Sector Consultants and Chris Kolb of the Michigan Environmental Council (co-chairs) and Dr. Matthew Davis of the University of Michigan Health System, Eric Rothstein of the Galardi Rothstein Group and Dr. Lawrence Reynolds of Mott Children's Health Center in Flint.[49] In December 29, 2015, the Task Force released its preliminary report, saying that the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) bore ultimate blame for the Flint water crisis.[50][51] The task force wrote that the DEQ's Office of Drinking Water and Municipal Assistance (ODWMA) adopted a "minimalist technical compliance approach" to water safety, which was "unacceptable and simply insufficient to the task of public protection."[50] The task force also found that "Throughout 2015, as the public raised concerns and as independent studies and testing were conducted and brought to the attention of MDEQ, the agency's response was often one of aggressive dismissal, belittlement, and attempts to discredit these efforts and the individuals involved. We find both the tone and substance of many MDEQ public statements to be completely unacceptable."[50] The task force also found that the Michigan DEQ has failed to follow the federal Lead and Copper Rule (LCR).[50] That rule requires "optimized corrosion control treatment," but DEQ staff instructed City of Flint water treatment staff that corrosion control treatment (CCT) would not be necessary for a year.[50] The task force found that "the decision not to require CCT, made at the direction of the MDEQ, led directly to the contamination of the Flint water system."[50]

The task force's findings prompted the resignation of DEQ director Dan Wyant and communications director Brad Wurfel.[52][53] Flint Department of Public Works director Howard Croft also resigned.[54]

On January 8, 2016, the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Eastern District of Michigan said that it was investigating.[20]

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) "battled Michigan's Department of Environmental Quality behind the scenes for at least six months over whether Flint needed to use chemical treatments to keep lead lines and plumbing connections from leaching into drinking water" and "did not publicize its concern that Flint residents' health was jeopardized by the state's insistence that such controls were not required by law.[55] In 2015, EPA water expert Miguel Del Toral "identified potential problems with Flint's drinking water in February, confirmed the suspicions in April and summarized the looming problem" in an internal memo[56] circulated on June 24, 2015.[55] The Del Toral memo was not publicly released until November 2015, after a revision and vetting process.[55] In the interim, the EPA and the Michigan DEQ engaged in a dispute on how to interpret the Lead and Copper Rule. According to EPA Region 5 Administrator Susan Hedman, the EPA pushed to immediately implement corrosion controls in the interests of public health, while the Michigan DEQ sought to delay a decision on corrosion control until two six-month periods of sampling had been completed.[55] In an interview with the Detroit News published on January 12, Hedman said: "Let's be clear, the recommendation to DEQ (regarding the need for corrosion controls) occurred at higher and higher levels during this time period. And the answer kept coming back from DEQ that 'no, we are not going to make a decision until after we see more testing results.'"[55] Hedman said the EPA did not go public with its concerns earlier because (1) state and local governments have primary responsibility for drinking water quality and safety; (2) there was insufficient evidence at that point of the extent of the danger; and (3) the EPA's legal authority to compel the state to take action was unclear, and the EPA discussed the issue with its legal counsel, who only rendered an opinion in November.[55] Hedman said the EPA discussed the issue with its legal counsel and urged the state to have MDHHS warn residents about the danger.[55] Hedman resigned from her position on January 21.[57]

Assessments of the EPA's action varied. Marc Edwards, who investigated the lead contamination, said that the assessment in Del Toral's original June memo was "100 percent accurate" and criticized the EPA for failing to take more immediate action.[55] State Senate Minority Leader Jim Ananich, Democrat of Flint, said, "There's been a failure at all levels to accurately assess the scale of the public health crisis in Flint, and that problem is ongoing. However, the EPA's Miguel Del Toral did excellent work in trying to expose this disaster. Anyone who read his memo and failed to act should be held accountable to the fullest extent of the law."[55]

On January 15, Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette announced that his office would open an investigation into the crisis, saying the situation in Flint "is a human tragedy in which families are struggling with even the most basic parts of daily life."[58][59]

Snyder announced he will release all of his emails from 2014 and 2015 regarding the crisis during his annual State of the State Address on January 19.[60]

State of emergency and emergency responses

On December 15, 2015, Mayor Weaver declared the water issue as a citywide public health state of emergency to prompt help from state and federal officials.[39] Weaver's declaration said that additional funding will be needed for special education, mental health, juvenile justice, and social services because of the behavioral and cognitive impacts of high blood lead levels.[20]

It was subsequently declared a countywide emergency by the Genesee County Board of Commissioners, and accepted as both by Governor Rick Snyder on January 5, 2016.[61] Snyder also apologized for the incident.[62]

On January 6, Snyder ordered the Michigan Emergency Operations Center, operated by the Michigan State Police Emergency Management and Homeland Security Division, to open a Joint Information Center to coordinate public outreach and field questions from the residents about the problems caused by the crisis.[63] The State Emergency Operations Center recommended that all Flint children under six years old get tested for lead levels as soon as possible, either by a primary care physician or the Genesee County Health Department.[64] The state has set up water resource sites at several public buildings around Flint where residents can pick up bottled water, water filters, replacement cartridges, and home water testing kits. They also advised residents to call the United Way to receive additional help if needed.[65] Weaver stressed to residents that it was important to also pick up the testing kits, as the city would like to receive at least 500 water test samples per week.[66]

Starting on January 7, Genesee County Sheriff Robert Pickell had work crews of offenders sentenced to community service begin delivering bottled water, water filters and replacement cartridges, primarily to residents living in homes built between 1901 and 1920, whose plumbing systems are most likely leaching lead into the water. The next week, he ordered his department to begin using reverse 911 to advise homebound residents on how to get help.[67]

On January 9, the United Auto Workers union also donated drinking water to Flint via a caravan of trucks to local food banks, and an AmeriCorps team announced that it would deploy to Flint to assist in response efforts.[68]

Also on January 9, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) sent two liaison officers to the Michigan Emergency Operations Center to work with the state to monitor the situation.[69][70]

On January 11, Snyder signed an executive order creating a new committee to "work on long-term solutions to the Flint water situation and ongoing public health concerns affecting residents."[71] The next day, officers from the Michigan State Police and Genesee County Sheriff's Department started delivering cases of water, water filters, lead testing kits and replacement cartridges to residents who needed them.[72] The American Red Cross has also been deployed to Flint to deliver bottled water and filters to residents.[73] Snyder activated the Michigan Army National Guard to assist the Red Cross, starting January 13,[74] with thirty soldiers planned to be in Flint by January 15.[75] The National Guard doubled their number of soldiers deployed to Flint by January 18, and began checking identification to assure the recipients were Flint residents, after it was discovered some people from as far away as Detroit were accepting free supplies over the weekend.[76] On January 19, Snyder ordered more soldiers to Flint by the next day, for a total of 200.[60]

On January 14, it was announced Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha will lead a Flint Pediatric Public Health Initiative that includes experts from the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, Hurley Children's Hospital, the Genesee County Health Department, and the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services to help Flint children diagnosed with lead poisoning.[77]

On January 15, Snyder asked President Obama to grant a federal emergency/major disaster designation for Genesee County, seeking federal financial aid for emergency assistance and infrastructure repair in order to "protect the health, safety and welfare of Flint residents."[75][78][79] The following day, Obama signed an emergency declaration giving Flint up to $5 million in federal aid to handle the crisis.[80] FEMA released a statement that said, "The President's action authorizes the Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), to coordinate all disaster relief efforts which have the purpose of alleviating the hardship and suffering caused by the emergency on the local population, and to provide appropriate assistance for required emergency measures, authorized under Title V of the Stafford Act, to save lives and to protect property and public health and safety, and to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe in Genesee County. FEMA is authorized to provide equipment and resources to alleviate the impacts of the emergency. Emergency protective measures, limited to direct federal assistance, will be provided at 75 percent federal funding. This emergency assistance is to provide water, water filters, water filter cartridges, water test kits, and other necessary related items for a period of no more than 90 days."[81] After Snyder's request for a "Major Disaster Declaration" status was turned down, FEMA Administrator W. Craig Fugate wrote a letter to Snyder saying that the water contamination "does not meet the legal definition of a 'major disaster'" under federal law because "[t]he incident was not the result of a natural catastrophe, nor was it created by a fire, flood or explosion."[82]

The federal response will be lead by the Department of Health and Human Services, with assistance from FEMA, the Small Business Administration, the EPA, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Department of Agriculture, the Office of Preparedness and Response, and the Public Health Service Commissioned Corps.[83]

On January 16, the Legacy Group Water Project coordinated with the Red Cross and the City of Flint as well as Bottles for the Babies to initiate the largest volunteer action to distribute water and filters into the city in a single day since a citywide emergency was declared on December 15, 2015.[84]

Lawsuits

On November 13, 2015, four families filed a federal class-action lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan in Detroit against Governor Rick Snyder and thirteen other city and state officials, including former Flint Mayor Dayne Walling and ex-emergency financial manager Darnell Earley, who was in charge of the city when the switch to the Flint River was made. The complaint alleges that the officials acted recklessly and negligently, leading to serious injuries from lead poisoning, including autoimmune disorders, skin lesions, and "brain fog."[85][86][87] The complaint says that the officials' conduct was "reckless and outrageous" and "shocks the conscience and was deliberately indifferent to ... constitutional rights."[87]

On January 14, 2016, a separate class-action lawsuit against Snyder, the State of Michigan, the City of Flint, Earley, Walling, and Croft was filed by three Flint residents in Michigan Circuit Court in Genesee County.[88][89]

Three additional class action lawsuits at county, state and federal levels were announced on January 19.[90]

Costs of infrastructure repairs and medical treatment

On January 7, 2016, Flint Mayor Karen Weaver said that estimates of the cost of fixing water infrastructure in Flint, such as aging pipes, range from millions up to $1.5 billion. These figures encompass infrastructure alone, excluding any public health costs of the disaster. DEQ interim director Keith Creagh said that estimation of total costs would be premature.[91][92] However, in a September 2015 email released by Snyder in January 2016, the state estimated the replacement cost to be $60 million, and said it could take up to 15 years to do so.[93]

On January 18, the United Way of Genesee County estimated 6,000–12,000 children have been exposed to lead poisoning and kicked off a fundraising campaign to raise $100 million over a 10–15 year span for their medical treatment.[1]

At his annual State of the State address on January 19, Snyder apologized again, and asked the Michigan Legislature to give Flint an additional $28 million in funding for filters, replacement cartridges, bottled water, more school nurses and additional intervention specialists. It also will fund lab testing, corrosion control procedures, a study of water-system infrastructure, potentially help Flint deal with unpaid water bills, case management of people with elevated lead-blood levels, assessment of potential linkages to other diseases, crisis counseling and mental health services, and the replacement of plumbing fixtures in schools, child care centers, nursing homes and medical facilities.[60] The Legislature is expected to enact the proposal.[94]

Political responses

White House

President Barack Obama said of the crisis, "What is inexplicable and inexcusable is once people figured out that there was a problem there, and that there was lead in the water, the notion that immediately families weren't notified, things weren't shut down. That shouldn't happen anywhere."[95]

Michigan congressional delegation

On January 20, Senator Debbie Stabenow, a Democrat, faulted the state for having "no sense of urgency whatsoever" despite warnings from the EPA about the contaminated water.[96] Senator Gary Peters, also a Democrat, said that: "The water crisis in Flint is an immense failure on the part of the State of Michigan to protect the health and safety of the City's residents, and the State must accept full responsibility for its actions that led to this catastrophe." Peters, along with Stabenow and Representative Dan Kildee, called upon the state to make a "sustained financial commitment" to assist Flint "by establishing a 'Future Fund' to meet the cognitive, behavioral and health challenges" of children affected by lead poisoning. Peters also called upon the state to reimburse Flint residents for the money that was paid for contaminated water, to pay the city's legal fees in connection with the water crisis, and to pay for the costs of reconnecting to the Detroit water system.[97]

On January 12, Kildee, Democrat of Flint, said of Snyder: "It's beyond my comprehension that he continues to treat this as a public relations problem rather than as a public health emergency. Meanwhile, kids in Flint are still being exposed to high levels of lead in the water." Kildee called upon Snyder to request federal assistance (which Snyder subsequently did).[98]

On January 14, Representative Brenda Lawrence, Democrat of Southfield formally requested congressional hearings on the crisis, saying: "We trust our government to protect the health and safety of our communities, and this includes the promise of clean water to drink..."[99]

Among the Michigan congressional delegation, only Representative Justin Amash, Republican of Cascade Township, opposed federal aid for Flint. Amash opined that "the U.S. Constitution does not authorize the federal government to intervene in an intrastate matter like this one."[100]

State legislature

On January 4, 2016, citing the Flint water crisis, Michigan Representative Phil Phelps, Democrat of Flushing, announced plans to introduce a bill to the Michigan House of Representatives that would make it a felony for state officials to intentionally manipulate or falsify information in official reports, punishable by up to five years' imprisonment and a $5,000 fine.[101]

Presidential candidates

Among the candidates for the Democratic nomination for president, Secretary of State and U.S. Senator Hillary Clinton said of the crisis: "The people of Flint deserve to know the truth about how this happened and what Governor Snyder and other leaders knew about it. And they deserve a solution, fast. Thousands of children may have been exposed to lead, which could irreversibly harm their health and brain functioning. Plus, this catastrophe—which was caused by a zeal to save money at all costs—could actually cost $1.5 billion in infrastructure repairs."[102] In a subsequent interview, Clinton referred to her work on lead abatement in housing in upstate New York and called for further funding for healthcare and education for children who will suffer the negative effects of lead exposure on behavior and educational attainment.[103] Independent U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, another candidate for the Democratic nomination for president, called for Snyder to resign from office, stating he has "no excuses" for the disaster.[104] He noted the event was "one of the worst public health crises in the modern history of this country."[105] Both Clinton and Sanders referenced the issue and condemned Snyder in a televised primary debate on January 17. Clinton stated that if the water crisis had occurred in a wealthier Detroit suburb rather than poor, majority African American Flint, "there would have been action," while Sanders reiterated his call for Snyder's resignation.[106][107][108]

Among Republican candidates, Senator Marco Rubio of Florida, declined to comment, saying that he had not been briefed and his campaign had not focused on the issue.[109][110] Donald Trump also said little about the crisis, simply stating "It’s a shame what's happening in Flint, Michigan. A thing like that shouldn’t happen."[111] Senator Ted Cruz of Texas said of the crisis that government is to blame and should be held accountable for exposing residents to "poisoned water." He also said the situation was a travesty and a failure of government at every level.[111] Governor John Kasich of Ohio said that a solution needed to be found and that "I think the governor has moved the National Guard in and, you know, I'm sure he will manage this appropriately."[111] Dr. Ben Carson, a Detroit native, said of the crisis, "Unfortunately, the leaders of Flint have failed to place the well-being of their residents as a top priority. The people deserve better from their local elected officials, but the federal bureaucracy is not innocent in this as well. Reports show that the Environmental Protection Agency knew well-beforehand about the lack of corrosion controls in the city’s water supply, but was either unwilling or unable to address the issue."[112]

Media and other responses

On October 8, 2015, the editorial board of the Detroit Free Press wrote that the crisis was "an obscene failure of government" and criticized Snyder.[113]

On December 31, 2015, the editorial board of the MLive group of Michigan newspapers (including The Flint Journal) called upon Snyder to "drop executive privilege and release all of his communications on Flint water," establish a procedure for compensating families with children suffering from elevated lead blood levels, and return Flint to local control.[114]

In January 2016, the watchdog group Common Cause also called upon Snyder to release all documents related to the Flint water crisis. (The governor's office is not subject to the Michigan Freedom of Information Act).[115]

MSNBC host Rachel Maddow has extensively reported on the water crisis on her show since December 2015, keeping it in the national spotlight.[116][117] She has condemned Snyder's use of emergency managers (which she termed a "very, very radical" change "to the way we govern ourselves as Americans, something that nobody else has done") and stated that "The kids of Flint, Michigan have been poisoned by a policy decision."[117]

The documentary filmmaker Michael Moore, a native of nearby Davison, called for Snyder's arrest for mishandling the water crisis in an open letter to the governor, writing: "The facts are all there, Mr. Snyder. Every agency involved in this scheme reported directly to you. The children of Flint didn't have a choice as to whether or not they were going to get to drink clean water." A spokesman for the governor called Moore's call "inflammatory."[118][119] Later, after hearing of the Legionnaires' outbreak, Moore termed the state's actions "murder."[120] Speaking to reporters in Flint, he emphasized that "this was not a mistake . . . Ten people have been killed here because of a political decision. They did this. They knew."[121]

In a post on her Facebook page, environmental activist Erin Brockovich called the water crisis a "growing national concern" and said that the crisis was "likely" connected to the Legionnaires' disease outbreak. Brockovich called for the U.S. Environment Protection Agency to become involved in the investigation, saying that the EPA's "continued silence has proven deadly."[120]

On January 16, the Reverend Jesse Jackson met with Mayor Weaver in Flint and said of the crisis, "The issue of water and air and housing and education and violence are all combined. The problem here obviously is more than just lack of drinkable water. We know the problems here and they will be addressed."[122] Jackson called Flint "a disaster zone" and a "crime scene" during a rally at a Flint church the next day.[123]

Also on January 16, singer Cher donated 181,000 bottles of water to Flint.[124] On January 18, rapper Meek Mill donated $50,000 to Flint to aid in the crisis.[125] The Little River Band of Ottawa Indians also donated $10,000 to Flint.[126] Rappers Big Sean and Sean Combs have also commented on the crisis, echoing the thoughts of other celebrities.[127] The next day, Terrance Knighton and his Washington Redskins teammates donated 3,600 bottles of water to Flint.[128] Ontario Hockey League teams the Windsor Spitfires and the Sarnia Sting (both rivals of the Flint Firebirds) have donated 15,000 bottles of water to Flint.[129]

Also on January 18, Nontombi Naomi Tutu (daughter of Desmond Tutu) said in a speech at the University of Michigan–Flint, "We actually needed the people of Flint to remind the people of this country what happens when political expediency, when financial concerns, overshadow justice and humanity."[130]

The water disaster also called attention to the problem of aging and seriously neglected water infrastructure nationwide.[131]

A number of commentators framed the crisis in terms of human rights, writing that authorities' handling of the issue denied residents their right to clean water.[45][132] Others framed it as the end result of austerity measures given priority over human life.[133][134] Others, such as columnist Shaun King, characterized the crisis as a result of environmental racism and "a horrific clash of race, class, politics and public health."[135]

On January 21, Reason Magazine's Robby Soave zeroed in on administrative bloat in the public service unions: "Let’s not forget the reason why local authorities felt the need to find a cheaper water source: Flint is broke and its desperately poor citizens can’t afford higher taxes to pay the pensions of city government retirees. As recently as 2011, it would have cost every person in Flint $10,000 each to cover the unfunded legacy costs of the city’s public employees."[136]

During its winter 2016 semester, the University of Michigan–Flint is offering a 1-credit, 8-session series of public forums dedicated to educating Flint residents and students on the crisis. [137]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b c United Way estimates cost of helping children $100M WNEM-TV, January 18, 2016

- ^ a b Khalil AlHajal, 87 cases, 10 fatal, of Legionella bacteria found in Flint area; connection to water crisis unclear, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 13, 2016).

- ^ President Obama Signs Michigan Emergency Declaration Official White House press release, January 16, 2016

- ^ 50 years later: Ghosts of corruption still linger along old path of failed Flint water pipeline The Flint Journal via MLive, November 12, 2012

- ^ a b Sam Gringlas, In Flint, lead contamination spurs fight for clean water, Michigan Daily (December 3, 2016).

- ^ Appendix B: Water System Roster, Detroit Water and Sewerage Department: The First 300 Years (ed. Michael Daisy), Detroit Water and Sewerage Department.

- ^ "Flint council supports buying water from Lake Huron through KWA". MLive.com. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "Flint emergency manager endorses water pipeline, final decision rests with state of Michigan". MLive.com. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "Detroit to state: Stop Flint's participation in new water pipeline". MLive.com. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "State gives Flint OK to join Karegnondi Water Authority project, but Detroit gets to make final offer". MLive.com. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "Detroit gives notice: It's terminating water contract covering Flint, Genesee County in one year". MLive.com. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ a b Water War Undermines Flint-DWSD Relations Official City of Detroit press release, April 1, 2013

- ^ Fonger, Ron (May 10, 2011). "DTE Energy tells new regional authority it may want 3 million gallons of Lake Huron water daily". Flint Journal. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ^ Adams, Dominic (March 25, 2013). "Flint council supports buying water from Lake Huron through KWA". Flint Journal. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Fonger, Ron (March 29, 2013). "Flint emergency manager endorses water pipeline, final decision rests with state of Michigan". Flint Journal. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Fonger, Ron (April 2, 2013). "Detroit 'water war' claims 'wholly without merit,' Genesee County drain commissioner says". Flint Journal. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ a b Fonger, Ron (April 19, 2013). "Detroit gives notice: It's terminating water contract covering Flint, Genesee County in one year". Flint Journal. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ a b Winston, Samuel (October 7, 2015). "How the Flint water crisis emerged". Flint Journal. p. 2. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "City switch to Flint River water slated to happen Friday". The Flint Journal. April 24, 2014 – via MLive.

- ^ a b c Greg Botelho, Sarah Jorgensen & Joseph Netto, Water crisis in Flint, Michigan, draws federal investigation, CNN (January 9, 2016).

- ^ Fonger, Ron (February 25, 2015). "Detroit offers Flint alternative to using river for long-term water backup". Flint Journal. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Schuch, Sarah (October 7, 2015). "How the Flint water crisis emerged". Flint Journal. p. 4. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Winston, Samuel (October 7, 2015). "How the Flint water crisis emerged". Flint Journal. p. 3. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "Flint returning to Detroit water amid lead concerns". CNN. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "Contaminants Found in Flint, Michigan, Drinking Water; City to Reconnect to Detroit Water Supply". The Weather Channel. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "Flint will pay for independent water tests, added phosphate treatment". MLive. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Mark Brush, Gov. Snyder moves to come up with $12 million to switch Flint's water back to Detroit's supply, Michigan Radio (October 8, 2015).

- ^ John Wisely, Snyder announces $12-million plan to fix Flint water, Detroit Free Press (October 8, 2015).

- ^ Stephanie Parkinson, Sen. Ananich calls for emergency funding from the state to address Flint water crisis, WEYI-TV (January 13, 2016).

- ^ Ron Fonger, With just 17 miles to go, KWA pipeline work might not stop for mild winter, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 5, 2016).

- ^ "Flint city councilman: 'We got bad water'". Detroit Free Press. Associated Press. January 14, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "A timeline of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan". Washington Post. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c Ron Fonger, Lead leaches into 'very corrosive' Flint drinking water, researchers say, MLive (September 2, 2015, updated September 3, 2015).

- ^ a b c d e f Robin Erb, Flint doctor makes state see light about lead in water, Detroit Free Press (October 12, 2015).

- ^ a b c Ron Fonger, Documents show Flint filed false reports about testing for lead in water, MLive (November 12, 2015, updated November 19, 2015).

- ^ "Engineering's Marc Edwards heads to Flint as part of study into unprecedented corrosion problem". Virginia Tech. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Oliver Lazarus, In Flint, Michigan, a crisis over lead levels in tap water, Public Radio International (January 7, 2016).

- ^ Ryan Felton, Governor Rick Snyder 'very sorry' about Flint water lead levels debacle, The Guardian (December 30, 2015).

- ^ a b Wang, Yanan (December 15, 2015). "In Flint, Mich., there's so much lead in children's blood that a state of emergency is declared". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ^ a b Steve Carmody, Virginia Tech ending Flint water investigation, Michigan Radio (January 11, 2016).

- ^ a b c Paul Egan, Virginia Tech wrapping up its work on Flint water, Detroit Free Press (January 12, 2016).

- ^ VA Tech Professor says Flint River water and Legionnaires Disease could be linked, WJRT-TV (January 13, 2016).

- ^ Source of deadly Flint Legionnaires' outbreak still unknown, new report says The Flint Journal via MLive, January 21, 2016

- ^ a b c d e f Ron Fonger, Public never told, but investigators suspected Flint River tie to Legionnaires' in 2014, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 16, 2016).

- ^ a b c David A. Graham, What Did the Governor Know About Flint's Water, and When Did He Know It?, The Atlantic (January 9, 2016).

- ^ a b c John Wisely, Were Flint water fears 'blown off' by state?, Detroit Free Press (January 7, 2016).

- ^ a b Ron Fonger, Flint data on lead water lines stored on 45,000 index cards, MLive (October 1, 2015).

- ^ Lindsey Smith, After ignoring and trying to discredit people in Flint, the state was forced to face the problem, Michigan Radio (December 16, 2015).

- ^ Gov. Rick Snyder announces Flint Water Task Force to review state, federal and municipal actions, offer recommendations, Office of the Governor (press release) (October 21, 2015).

- ^ a b c d e f Jiquanda Johnson, Four takeaways from the Flint Water Advisory Task Force preliminary report, MLive (December 30, 2015).

- ^ Vincent Duffy, Task force lays most blame for Flint water crisis on MDEQ, Michigan Radio (December 29, 2015).

- ^ Emily Lawler, Director Dan Wyant resigns after task force blasts MDEQ over Flint water crisis, The Flint Journal via MLive (December 29, 2015).

- ^ Emily Lawler, DEQ spokesman also resigns over Flint water crisis, says city 'didn't feel like we cared', MLive (December 30, 2015).

- ^ Ron Fonger, Howard Croft, Flint official responsible for water oversight, resigns, The Flint Journal via MLive (November 16, 2015).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jim Lynch, EPA stayed silent on Flint's tainted water, The Detroit News (January 12, 2016).

- ^ Del Toral, Miguel (June 24, 2015). "Memorandum: High Levels of Lead in Flint, Michigan – Interim Report (Original)" (PDF). US EPA and ACLU Michigan. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ Top EPA official in Midwest resigning amid Flint crisis The Detroit News, January 21, 2016

- ^ Associated Press, Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette plans to open investigation on Flint water crisis (January 15, 2016).

- ^ Scott Atkinson, Amy Haimerl & Richard Pérez-Peña, Anger and Scrutiny Grow Over Poisoned Water in Flint, Michigan, The New York Times (January 15, 2016).

- ^ a b c What Gov. Snyder plans to do about Flint water crisis WJRT-TV, January 19, 2016

- ^ Governor declares state of emergency over lead in Flint water, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 5, 2016).

- ^ Felton, Ryan. "Governor Rick Snyder 'very sorry' about Flint water lead levels debacle". The Guardian. London. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ Amanda Emery, State launches information center for Flint following emergency declaration, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 6, 2016).

- ^ Emily Lawler, 43 Flint residents identified with elevated lead levels so far, urged to take precautions, MLive (January 7, 2016).

- ^ New water resource sites now open in Flint, WJRT-TV (January 10, 2016).

- ^ Roberto Acosta, Flint water resource teams to cover city, mayor stresses test kit importance, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 10, 2016).

- ^ Molly Young, Sheriff uses reverse 911 for Flint residents who need water help, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 11, 2016).

- ^ Associated Press, UAW members donate drinking water to Flint residents; Americorps to begin effort (January 9, 2016).

- ^ Amanda Emery, Federal Emergency Management Agency to monitor Flint's water crisis, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 9, 2016).

- ^ Paul Egan, Federal disaster agency monitoring Flint water crisis, Detroit Free Press (January 9, 2016).

- ^ Ron Fonger, Gov. Snyder signs executive order to create new Flint water committee, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 11, 2016).

- ^ Roberto Acosta, Crisis teams hit Flint streets with filters and water for frustrated residents, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 12, 2016).

- ^ Natalie Zarowny, Red Cross volunteers come to help Flint from across the state, country, WJRT-TV (January 12, 2016).

- ^ Ron Fonger, Governor activates National Guard to deal with Flint water crisis, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 12, 2016).

- ^ a b Matthew Dolan, Snyder seeks federal emergency status over Flint water, Detroit Free Press (January 15, 2016).

- ^ National Guard doubles troops handing out water in Flint WJRT-TV, January 18, 2016

- ^ Flint organizations announce Pediatric Public Health Initiative, WJRT-TV (January 14, 2016).

- ^ Gary Ridley, Snyder asks Obama to declare federal emergency for Flint water, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 14, 2016).

- ^ Chad Livengood, Jonathan Oosting & Melissa Nann Burke, White House to decide soon on Flint emergency request, Detroit News (January 15, 2016).

- ^ Ashley Southall, [State of Emergency Declared Over Man-Made Water Disaster in Michigan City], New York Times (January 17, 2016).

- ^ Roberto Acosta, President Obama signs emergency declaration over Flint's water crisis The Flint Journal via MLive (January 16, 2016)

- ^ Chad Livengood & Jonathan Oosting, Snyder to appeal Obama's denial of Flint disaster zone, Detroit News (January 18, 2016).

- ^ U.S. Health and Human Services to lead federal response of Flint water crisis, WEYI-TV (January 19, 2016).

- ^ Truckloads of water to be delivered to Flint senior centers, WJRT-TV (January 15, 2016).

- ^ Pitt, Michael L.; McGehee, Cary S.; Rivers, Beth M. (November 13, 2015). "Melisa Mays, et. al. vs. Governor Rick Snyder, et. al" (PDF). Pitt Law PC. 2:15-cv-14002-JCO-MKM. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

Defendants' conduct in exposing Flint residents to toxic water was so egregious and so outrageous that it shocks the conscience.

- ^ "4 families sue over lead in Flint water". The Detroit News. November 15, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ a b Daniel Bethencourt, After Flint water crisis, families file lawsuit, Detroit Free Press (November 13, 2015).

- ^ 3 people file class action lawsuit against Gov. Snyder, Flint, WJRT-TV (January 14, 2016).

- ^ State of Michigan, Gov. Snyder sued in class action lawsuit over Flint water crisis, WDIV-TV (January 14, 2016).

- ^ Three water-related class action lawsuits filed by Flint residents Three water-related class action lawsuits filed by Flint residents WJRT-TV, January 19, 2016

- ^ Emily Lawler, Flint infrastructure fix could cost up to $1.5B, mayor Karen Weaver says, MLive (January 7, 2016, updated January 8, 2016).

- ^ Cost to fix Flint water infrastructure could reach $1.5 billion: reports, Reuters (January 7, 2016).

- ^ 15 years and $60M needed to replace Flint's lead water lines, emails show The Flint Journal via MLive, January 20, 2016

- ^ Emily Lawler, Key Michigan lawmakers say $28M Flint aid request will move swiftly, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 19, 2016).

- ^ Obama Calls Flint Water Crisis 'Inexplicable And Inexcusable', The Huffington Post (January 20, 2016).

- ^ Stabenow tells CNN 'no sense of urgency' by state in Flint water crisis, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 20, 2016).

- ^ Wil Hunter, U.S. Senator Gary Peters' statement on Governor Snyder's State of the State (Jabnuary 20, 2016).

- ^ Congressman Kildee on Amir Hekmati, Snyder's response to Flint water crisis, Michigan Radio (January 11, 2016).

- ^ Ron Fonger, Congresswoman makes formal request for federal Flint water hearings, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 14, 2016).

- ^ Nate Reens, Justin Amash stood alone opposing Flint water federal aid bid, MLive (January 19, 2016).

- ^ Emily Lawler, Bill inspired by Flint water crisis would make data manipulation by Michigan officials a felony, MLive (January 4, 2016).

- ^ Hillary Clinton speaks out on Flint's water emergency, WJRT-TV (January 11, 2016).

- ^ Amanda Emery, Hillary Clinton infuriated by Flint water crisis, outraged by Gov. Snyder The Flint Journal via MLive (January 14, 2016).

- ^ Martin Pengelly, Obama declares Flint water emergency as Sanders blames Michigan governor, The Guardian (January 16, 2016).

- ^ Chad Livengood, Sanders: Snyder should resign over Flint water crisis, The Detroit News (January 16, 2016).

- ^ Roberto Acosta, Hillary Clinton addresses Flint water crisis during presidential debate, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 17, 2016).

- ^ Jason Linkins, Flint's Water Problem Finally Gets Attention During A Debate, Huffington Post (January 17, 2015).

- ^ Daniel White, Michigan Governor Upset About Democratic Debate Mention, Time (January 18, 2016).

- ^ Eric Bradner, Rubio says he hasn't been briefed on Flint water crisis, CNN (January 19, 2015).

- ^ Tony Paul, Rubio declines detailed comment on Flint water crisis, Detroit News (January 18, 2016).

- ^ a b c Donald Trump, Rubio Try to Stay Clear of Flint Water Crisis The Wall Street Journal, January 19, 2016

- ^ Ben Carson Becomes First GOP Candidate To Weigh In On Flint Water Crisis The Huffington Post (January 19, 2016).

- ^ Flint water crisis: An obscene failure of government, Detroit Free Press (October 8, 2015).

- ^ Gov. Rick Snyder needs to do more than just apologize for Flint water crisis, MLive (December 31, 2015).

- ^ Steve Carmody, Watchdog group asks Gov. Snyder to release all Flint water crisis documents, Michigan Radio (January 6, 2016).

- ^ Ron Fonger, MSNBC's Rachel Maddow keeps national spotlight on water crisis in Michigan, MLive (December 23, 2015).

- ^ a b Rachel Maddow Slams Rick Snyder For 'Poisoning Flint's Children' With Water Crisis, CBS Detroit (December 19, 2015).

- ^ Michael Moore calls for arrest of Gov. Snyder, Detroit News (January 7, 2016).

- ^ Chris Fleszar, Michael Moore calls for Snyder's arrest for Flint water, WZZM 13 (republished by the Detroit Free Press) (January 7, 2016).

- ^ a b Erin Brockovich, Michael Moore join outcry about Flint area Legionnaires' spike The Flint Journal via MLive (January 14, 2016).

- ^ Daniel Bethencourt, Michael Moore, in Flint, says crisis 'not a mistake', Detroit Free Press (January 16, 2016).

- ^ Mayor Weaver and Rev. Jesse Jackson discuss emergency declaration and water emergency, WJRT-TV (January 16, 2016).

- ^ Roberto Acosta, Rev. Jesse Jackson calls Flint a "disaster zone," asks for federal help The Flint Journal via MLive (January 17, 2016).

- ^ Cher to donate 181,000 bottles of water to help out Flint water crisis The Flint Journal via MLive (January 16, 2016).

- ^ Meek Mill Promises to Donate Money to Flint Water Crisis, Asks 50 Cent to Help, XXL Magazine (January 18, 2016).

- ^ Little River Band tribe offers $10,000 donation to help Flint water crisis The Flint Journal via MLive, January 19, 2016

- ^ Rappers Big Sean, Meek Mill pledge aid to Flint water crisis The Flint Journal via MLive (January 19, 2016).

- ^ Washington Redskins players jump in for help with Flint water crisis The Flint Journal via MLive (January 20, 2016).

- ^ Support for Flint goes International as Ontario Hockey League teams pitch in WEYI-TV, January 21, 2016

- ^ Daughter of Desmond Tutu speaks on Flint water crisis at MLK Day event, The Flint Journal via MLive (January 18, 2016).

- ^ Lead Poisoning In Michigan Highlights Aging Water Systems Nationwide, NPR Weekend Edition Saturday (January 2, 2016) (interview with Robert Puentes, director of the Metropolitan Infrastructure Initiative at the Brookings Institution).

- ^ Benjamin Spoer, Flint's water crisis is a human rights violation, Al Jazeera (January 9, 2016).

- ^ When money matters more than lives: The poisonous cost of austerity in Flint, Michigan. Salon. January 9, 2016.

- ^ John Nichols. Outcry Over the Austerity Crisis in Flint Grows. The Nation. January 17, 2015.

- ^ Shaun King, King: Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder did nothing as Flint’s water crisis became one of the worst cases of environmental racism in modern American history, Daily News (New York) (January 11, 2016).

- ^ The Government Poisoned Flint’s Water—So Stop Blaming Everyone Else Reason Magazine, January 21, 2016

- ^ UM-Flint kicks off first of 8 forums dedicated to the Flint Water Crisis WJRT-TV, January 22, 2016

External links

| External videos | |

|---|---|

- Taking Action on Flint Water – official Michigan Department of Environmental Quality website on the crisis

- EPA documents related to Flint drinking water – from the official EPA website

- Flintwaterstudy.org – official website of Dr. Marc Edwards' Virginia Tech Research Team, which investigated the lead contamination

- Articles on the Flint water crisis from MLive

- 2014 disasters in the United States

- 2014 health disasters

- 2014 in Michigan

- 2014 in the environment

- 2015 disasters in the United States

- 2015 health disasters

- 2015 in Michigan

- 2015 in the environment

- 2016 disasters in the United States

- 2016 health disasters

- 2016 in Michigan

- 2016 in the environment

- Cover-ups

- Economy of Flint, Michigan

- Environment of Michigan

- Flint, Michigan

- Health disasters in the United States

- Health in Michigan

- Lead poisoning incidents

- Ongoing events

- Water supply and sanitation in the United States