Frisian languages

| Frisian | |

|---|---|

| Frysk | |

| |

| Native to | Netherlands, Denmark and Germany |

| Region | Friesland, Groningen, Lower Saxony, Schleswig-Holstein |

| Ethnicity | Frisians |

Native speakers | 480,000 (ca. 2001 census)[1] |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

| Latin | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Netherlands Germany |

| Regulated by | NL: Fryske Akademy D: no official regulation unofficial: the Seelter Buund (for Sater Frisian), the Nordfriisk Instituut (for North Frisian) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:fry – West Frisianfrr – North Frisianstq – Saterland Frisian |

| Glottolog | fris1239 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ACA |

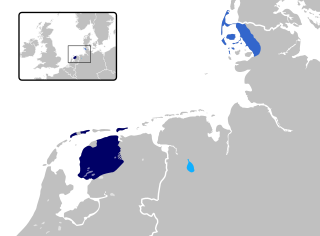

Present-day distribution of the Frisian languages in Europe:

| |

The Frisian /ˈfriːʒən/[2] languages are a closely related group of Germanic languages, spoken by about 500,000 Frisian people, who live on the southern fringes of the North Sea in the Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark. The Frisian languages are the closest living language group to English languages, and are together grouped into the Anglo-Frisian languages. However, modern English and Frisian are mutually unintelligible. Rather, the three Frisian languages have been heavily influenced by and bear similarities to Dutch, Danish, and/or Low German, depending upon their respective locations. Additional shared linguistic characteristics between the Great Yarmouth area, Friesland, and Denmark are likely to have resulted from the close trading relationship these areas maintained during the centuries-long Hanseatic League of the Late Middle Ages.[3]

Division

There are three varieties of Frisian: West Frisian, Saterland Frisian, and North Frisian. Some linguists consider these three varieties, despite their mutual unintelligibility, to be dialects of one single Frisian language, whereas others consider them to be three separate languages, as do their speakers. West Frisian is strongly influenced by Dutch, and, similar to Dutch, is described as being "between" English and German. The other Frisian varieties, meanwhile, have been influenced by German, Low German, and Danish. The North Frisian language especially is further segmented into several strongly diverse dialects. Stadsfries is not Frisian, but a Dutch dialect influenced by Frisian. Frisian is called Frysk in West Frisian, Fräisk in Saterland Frisian, and Frasch, Fresk, Freesk, and Friisk in the dialects of North Frisian.

The situation in the Dutch province of Groningen and the German region of East Frisia is more complex: The local Low Saxon dialects of Gronings and East Frisian Low Saxon are a mixture of Frisian and Low Saxon dialects; it is believed that Frisian was spoken there at one time, only to have been gradually replaced by the language of the city of Groningen. This local language is now, in turn, being replaced by standard Dutch.

Speakers

Most Frisian speakers live in the Netherlands, primarily in the province of Friesland, since 1997 officially using its West Frisian name of Fryslân, where the number of native speakers is about 400,000,[4] which is about 75% of the inhabitants of Friesland.[5] An increasing number of native Dutch speakers in the province are learning Frisian as a second language.

In Germany, there are about 2,000[6] speakers of Saterland Frisian in the Saterland region of Lower Saxony; the Saterland's marshy fringe areas have long protected Frisian speech there from pressure by the surrounding Low German and standard German,[citation needed] but Saterland Frisian still remains seriously endangered because of its exclusion to agrarian community and its lack of a sizable and educated community to help preserve and spread the language.[5]

In the North Frisia (Nordfriesland) region of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein, there were 10,000 North Frisian speakers in the 1970s.[1] Although many of these live on the mainland, most are found on the islands, notably Sylt, Föhr, Amrum, and Heligoland. The local corresponding North Frisian dialects are still in use.

As a regional language in the Netherlands, Frisian is only spoken by a certain demographic, specifically rural, lower-class people[7] in contrast with the Dutch speaking upper-class.

Frisian-Dutch bilinguals are split into two categories: Speakers who had Dutch as their first language tended to maintain the Dutch system of homophony between plural and linking suffixes when speaking Frisian, by using the Frisian plural as a linking morpheme. Speakers who had Frisian as their first language often maintained the Frisian system of no homophony when speaking Frisian.

Speakers of the many dialects of Frisian may also be found in the United States.

Status

Saterland and North Frisian[8] are officially recognised and protected as minority languages in Germany, and West Frisian is one of the two official languages in the Netherlands, the other being Dutch.

ISO 639-1 code fy and ISO 639-2 code fry were assigned to "Frisian", but that was changed in November 2005 to "Western Frisian". According to the ISO 639 Registration Authority the "previous usage of [this] code has been for Western Frisian, although [the] language name was "Frisian".[9]

The new ISO 639 code stq is used for the Saterland Frisian language, a variety of Eastern Frisian (not to be confused with East Frisian Low Saxon, a West Low German dialect). The new ISO 639 code frr is used for the North Frisian language variants spoken in parts of Schleswig-Holstein.

The Ried fan de Fryske Beweging is an organization which works for the preservation of the Frisian language and culture in the Dutch province of Friesland. The Fryske Academy also plays a large role, since its foundation in 1938, to conduct research on Frisian language, history, and society, including attempts at forming a larger dictionary.[4] Recent attempts have allowed Frisian be used somewhat more in some of the domains of education, media and public administration.[10] Nevertheless, Saterland Frisian and most dialects of North Frisian are seriously endangered[11] and West Frisian is considered as vulnerable to being endangered.[12] Moreover, for all advances in integrating Frisian in daily life, there is still a lack of education and media awareness of the Frisian language, perhaps reflecting its rural origins and its lack of prestige[13] Therefore, in a sociological sense it is considered more a dialect than a standard language, even though linguistically it is a separate language.[13]

For L2 speakers, both the quality and amount of time Frisian is taught in the classroom is low, concluding that Frisian lessons do not contribute meaningfully to the linguistic and cultural development of the students.[4] Moreover, Frisian runs the risk of dissolving into Dutch, especially in Friesland, where both languages are used.[10]

History

Old Frisian

In the early Middle Ages the Frisian lands stretched from the area around Bruges, in what is now Belgium, to the river Weser, in northern Germany. At that time, the Frisian language was spoken along the entire southern North Sea coast. Today this region is sometimes referred to as Great Frisia or Frisia Magna, and many of the areas within it still treasure their Frisian heritage, even though in most places the Frisian languages have been lost.

Frisian is the language most closely related to English and Scots, but after at least five hundred years of being subject to the influence of Dutch, modern Frisian in some aspects bears a greater similarity to Dutch than to English; one must also take into account the centuries-long drift of English away from Frisian. Thus the two languages have become less mutually intelligible over time, partly due to the marks which Dutch and Low German have left on Frisian, and partly due to the vast influence some languages (in particular Norman French) have had on English throughout the centuries.

Old Frisian,[5] however, was very similar to Old English. Historically, both English and Frisian are marked by the loss of the Germanic nasal in words like us (ús; uns in German), soft (sêft; sanft) or goose (goes; Gans): see Anglo-Frisian nasal spirant law. Also, when followed by some vowels, the Germanic k softened to a ch sound; for example, the Frisian for cheese and church is tsiis and tsjerke, whereas in Dutch it is kaas and kerk, and in High German the respective words are Käse and Kirche. Contrarily, this did not happen for chin and choose, which are kin and kieze.[14][15]

One rhyme demonstrates the palpable similarity between Frisian and English: "Butter, bread and green cheese is good English and good Frise," which is pronounced more or less the same in both languages (Frisian: "Bûter, brea en griene tsiis is goed Ingelsk en goed Frysk.") [16]

One major difference between Old Frisian and modern Frisian is that in the Old Frisian period (c.1150-c.1550) grammatical cases still existed. Some of the texts that are preserved from this period are from the 12th or 13th, but most are from the 14th and 15th centuries. Generally, all these texts are restricted to legalistic writings. Although the earliest definite written examples of Frisian are from approximately the 9th century, there are a few examples of runic inscriptions from the region which are probably older and possibly in the Frisian language. These runic writings however usually do not amount to more than single- or few-word inscriptions, and cannot be said to constitute literature as such. The transition from the Old Frisian to the Middle Frisian period (c.1550-c.1820) in the 16th century is based on the fairly abrupt halt in the use of Frisian as a written language.

Middle Frisian

Up until the 15th century Frisian was a language widely spoken and written, but from 1500 onwards it became an almost exclusively oral language, mainly used in rural areas. This was in part due to the occupation of its stronghold, the Dutch province of Friesland (Fryslân), in 1498, by Duke Albert of Saxony, who replaced Frisian as the language of government with Dutch.

Afterwards this practice was continued under the Habsburg rulers of the Netherlands (the German Emperor Charles V and his son, the Spanish King Philip II), and even when the Netherlands became independent, in 1585, Frisian did not regain its former status. The reason for this was the rise of Holland as the dominant part of the Netherlands, and its language, Dutch, as the dominant language in judicial, administrative and religious affairs.

In this period the great Frisian poet Gysbert Japiks (1603–66), a schoolteacher and cantor from the city of Bolsward, who largely fathered modern Frisian literature and orthography, was really an exception to the rule.

His example was not followed until the 19th century, when entire generations of Frisian authors and poets appeared. This coincided with the introduction of the so-called newer breaking system, a prominent grammatical feature in almost all West Frisian dialects, with the notable exception of Southwest Frisian. Therefore, the Modern Frisian period is considered to have begun at this point in time, around 1820.

Modern Frisian

The revival of the Frisian Language comes from the poet Gysbert Japiks, who had begun to write in the language as a way to show that it was possible, and created a collective Frisian identity and Frisian standard of writing through his poetry.[17] Later on, Johannes Hilarides would build off Gysbert Japik's work by building on Frisian orthography, particularly on its pronunciation; he also, unlike Japiks, set a standard of the Frisian language that focused more heavily on how the common people used it as an everyday language.[17]

Perhaps the most important figure in the spreading of the Frisian language was J. H. Halbertsma (1789–1869), who translated many works into the Frisian language, such as the New Testament [17] He had however, like Hilarides, focused mostly on the vernacular of the Frisian language, where he focused on translating texts, plays and songs for the lower and middle classes in order to teach and expand the Frisian language.[17] This had begun the effort to continuously preserve the Frisian language, which continues unto this day. It was however not until the first half of the 20th century that the Frisian revival movement began to gain strength, not only through its language, but also through its culture and history, supporting singing and acting in Frisian in order to facilitate Frisian speaking.[13]

It was not until 1960 that Dutch began to dominate Frisian in Friesland; with many non-Frisian immigrants into Friesland, the language gradually began to diminish, and only survives now due to the constant effort of scholars and organisations.[17] The province of Friesland rather than the language itself has become in recent years a more important part of Frisian identity, so the language has become less important for cultural preservation purposes.[18] It is especially written Frisian that seems to have trouble surviving, with only 30% of the Frisian population competent in it;[19] it had disappeared in the 16th century and continues to be barely taught today.[20]

Family tree

Each of the Frisian languages has several dialects. Between some, the differences are such that they rarely hamper understanding; only the number of speakers justifies the denominator of "dialect". In other cases, even neighbouring dialects may hardly be mutually intelligible.

The Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages has a large number of speakers, approximately 450 million native speakers, partly due to the colonisation of many parts of the world. However, the number of different languages within the Germanic group is rather limited. Depending on the definition of what counts as a language there are about 12 different languages. Traditionally, they are divided into three subgroups: East Germanic (Gothic, which is no longer a living language), North Germanic (Icelandic, Faeroese, Norwegian, Danish, and Swedish), and West Germanic (English, German, Dutch, Afrikaans, Yiddish and Frisian). Some of these languages are so similar that they are only considered independent languages because of their position as standardised languages spoken within the limits of a state. This goes for the languages of the Scandinavian countries, Swedish, Danish and Norwegian, which are mutually intelligible. Other languages consist of dialects which are in fact so different that they are no longer mutually intelligible but are still considered one language because of standardisation. Northern and southern German dialects are an example of this situation.[14]

- West Frisian language, spoken in the Netherlands.

- Clay Frisian (Klaaifrysk)

- Wood Frisian (Wâldfrysk)

- South Frisian (Súdhoeks)

- Southwest Frisian (Súdwesthoeksk)

- Schiermonnikoogs

- Hindeloopen Frisian

- Aasters

- Westers

- East Frisian language, spoken in Lower Saxony, Germany.

- Saterland Frisian language

- Several extinct dialects

- North Frisian language, spoken in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.

- Mainland dialects

- Mooring

- Goesharde Frisian (Hoorning)

- Wiedingharde Frisian

- Halligen Frisian

- Karrharde Frisian

This is a small portion of the Frisian Family Tree.

- Island dialects

- Söl'ring

- Fering

- Öömrang

- Heligolandic (Halunder)

- Extinct dialects

- Mainland dialects

Text samples

The Lord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer in Standard Western Frisian (Frysk):

- Us Heit, dy't yn de himelen is

- jins namme wurde hillige.

- Jins keninkryk komme.

- Jins wollen barre,

- allyk yn 'e himel

- sa ek op ierde.

- Jou ús hjoed ús deistich brea.

- En ferjou ús ús skulden,

- allyk ek wy ferjouwe ús skuldners.

- En lied ús net yn fersiking,

- mar ferlos ús fan 'e kweade.

- [Want Jowes is it keninkryk en de krêft

- en de hearlikheid oant yn ivichheid.] "Amen"

The English translation in the 1662 Anglican Book of Common Prayer:

- Our Father, which art in Heaven

- Hallowed be thy Name.

- Thy Kingdom come.

- Thy will be done,

- in earth as it is in Heaven.

- Give us this day our daily bread.

- And forgive us our trespasses,

- As we forgive them that trespass against us.

- And lead us not into temptation;

- But deliver us from evil.

- [For thine is the kingdom, the power, and the glory,

- For ever and ever.] Amen.

(NB: Which was changed to "who", in earth to "on earth," and them that to "those who" in the 1928 version of the Church of England prayer book and used in other later Anglican prayer books too. However, the words given here are those of the original 1662 book as stated)

The Standard Dutch translation from the Dutch Bible Society

- Onze Vader die in de hemelen zijt,

- Uw naam worde geheiligd;

- Uw Koninkrijk kome;

- Uw wil geschiede,

- gelijk in de hemel alzo ook op de aarde.

- Geef ons heden ons dagelijks brood;

- en vergeef ons onze schulden,

- gelijk ook wij vergeven onze schuldenaren;

- en leid ons niet in verzoeking,

- maar verlos ons van de boze.

- [Want van U is het Koninkrijk

- "en de kracht en de heerlijkheid

- in der eeuwigheid.] Amen.

Comparative sentence

- Saterland Frisian: Die Wänt strookede dät Wucht uum ju Keeuwe un oapede hier ap do Sooken.

- North Frisian (Mooring dialect): Di dreng aide dåt foomen am dåt kan än mäket har aw da siike.

- West Frisian: De jonge streake it famke om it kin en tute har op 'e wangen.

- Gronings: t Jong fleerde t wicht om kinne tou en smokte heur op wange.

- East Frisian Low Saxon: De Fent/Jung straktde dat Wicht um't Kinn to un tuutjede hör up de Wangen.

- Template:Lang-nl

- Template:Lang-de

- Template:Lang-en

- Template:Lang-sv

- Template:Lang-da

- Template:Lang-no

See also

References

Notes

- ^ a b West Frisian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

North Frisian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

Saterland Frisian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required) - ^ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

- ^ Gooskens, Charlotte (2004). "The Position of Frisian in the Germanic Language Area". On the Boundaries of Phonology and Phonetics.

- ^ a b c Extra, Guus; Gorter, Durk (2001-01-01). The Other Languages of Europe: Demographic, Sociolinguistic, and Educational Perspectives. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 9781853595097.

- ^ a b c Bremmer, Rolf Hendrik (2009-01-01). An Introduction to Old Frisian: History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 9027232555.

- ^ "Gegenwärtige Schätzungen schwanken zwischen 1.500 und 2.500." Marron C. Fort: Das Saterfriesische. In: Horst Haider Munske, Nils Århammar: Handbuch des Friesischen – Handbook of Frisian Studies. Niemayer (Tübingen 2001).

- ^ "Frisian language use and ethnic identity: International Journal of the Sociology of Language". www.degruyter.com. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ^ Gesetz zur Förderung des Friesischen im öffentlichen Raum - Wikisource Template:De icon

- ^ Christian Galinski; Rebecca Guenther; Håvard Hjulstad. "Registration Authority Report 2004-2005" (PDF). p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-20. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ a b Fishman, Joshua A. (2001-01-01). Can Threatened Languages be Saved?: Reversing Language Shift, Revisited : a 21st Century Perspective. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 9781853594922.

- ^ Matthias Brenzinger, Language Diversity Endangered, Mouton de Gruter, The Hague: 222

- ^ "Atlas of languages in danger | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ^ a b c Deumert, Ana; Vandenbussche, Wim (2003-10-27). Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 9789027296306.

- ^ a b http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Charlotte_Gooskens/publication/237534065_The_Position_of_Frisian_in_the_Germanic_Language_Area/links/00463528e89b97127d000000.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "English to Frisian dictionary".

- ^ The History of English: A Linguistic Introduction. Scott Shay, Wardja Press, 2008, ISBN 0-615-16817-5, ISBN 978-0-615-16817-3

- ^ a b c d e Linn, Andrew R.; McLelland, Nicola (2002-12-31). Standardization: Studies from the Germanic languages. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 9789027283672.

- ^ Yngve, Victor; Wasik, Zdzislaw (2006-11-25). Hard-Science Linguistics. A&C Black. ISBN 9780826492395.

- ^ Yngve, Victor; Wasik, Zdzislaw (2006-11-25). Hard-Science Linguistics. A&C Black. ISBN 9780826492395.

- ^ Linn, Andrew Robert; McLelland, Nicola (2002-01-01). Standardization: Studies from the Germanic Languages. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 9027247471.

General references

External links

- The Frisian foundation

- Frisian-English dictionary

- [PDF]Hewett, Waterman Thomas, The Frisian language and literature

- 'Hover & Hear' Frisian pronunciations, and compare with equivalents in English and other Germanic languages.

- "Frisian: Standardisation in Progress of a Language in Decay" (PDF). (231 KiB)

- Description of language including audio files

- Frisian radio

- Radio news in North Frisian