Microlith

A microlith is a small stone tool usually made of flint or chert and typically a centimetre or so in length and half a centimetre wide. They were made by humans from around 35,000 years ago, across Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia. The microliths were used in spear points and arrowheads.

Microliths are produced from either a small blade (microblade) or a larger blade-like piece of flint by abrupt or truncated retouching, which leaves a very typical piece of waste, called a microburin. The microliths themselves are sufficiently worked so as to be distinguishable from workshop waste or accidents.

Two families of microliths are usually defined: laminar and geometric. An assemblage of microliths can be used to date an archeological site. Laminar microliths are slightly larger, and are associated with the end of the Upper Paleolithic and the beginning of the Epipaleolithic era; geometric microliths are characteristic of the Mesolithic and the Neolithic. Geometric microliths may be triangular, trapezoid or lunate. Microlith production generally declined following the introduction of agriculture (8000 BCE) but continued later in cultures with a deeply rooted hunting tradition.

Regardless of type, microliths were used to form the points of hunting weapons, such as spears and (in later periods) arrows, and other artifacts and are found throughout Africa, Asia and Europe. They were utilised with wood, bone, resin and fiber to form a composite tool or weapon, and traces of wood to which microliths were attached have been found in Sweden, Denmark and England. An average of between six and eighteen microliths may often have been used in one spear or harpoon, but only one or two in an arrow. The shift from earlier larger tools had an advantage. Often the haft of a tool was harder to produce than the point or edge: replacing dull or broken microliths with new easily portable ones was easier than making new hafts or handles.[1]

Types

[edit]

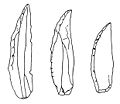

Laminar and non-geometric microliths

[edit]Laminar microliths date from at least the Gravettian culture or possibly the start of the Upper Paleolithic era, and they are found all through the Mesolithic and Neolithic eras. "Noailles" burins and micro-gravettes () indicate that the production of microliths had already started in the Gravettian culture.[2] This style of flint working flourished during the Magdalenian period and persisted in numerous Epipaleolithic traditions all around the Mediterranean basin. These microliths are slightly larger than the geometric microliths that followed and were made from the flakes of flint obtained ad hoc from a small nucleus or from a depleted nucleus of flint. They were produced either by percussion or by the application of a variable pressure (although pressure is the best option, this method of producing microliths is complicated and was not the most commonly used technique).[3]

Truncated blade

[edit]There are three basic types of laminar microlith. The truncated blade type can be divided into a number of sub-types depending on the position of the truncation (for example, oblique, square or double) and according to its form, for example, concave or convex. "Raclette scrapers" are notable for their particular form, being blades or flakes whose edges have been sharply retouched until they are semicircular or even shapeless. Raclettes are indefinite cultural indicators, as they appear from the Upper Paleolithic through to the Neolithic.

-

Flint blade

-

Truncated bladelet

-

Backed edge bladelet

-

Dufour bladelet

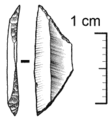

Backed edge blades

[edit]Backed edge blades have one of the edges, generally a side one, rounded or chamfered by abrupt retouching. There are fewer types of these blades, and may be divided into those where the entire edge is rounded and those where only a part is rounded, or even straight. They are fundamental in the blade-forming processes, and from them, innumerable other types were developed.[4] Dufour bladelets are up to three centimeters in length, finely shaped with a curved profile whose retouches are semi-abrupt and which characterize a particular phase of the Aurignacian period. Solutrean backed edge blades display pronounced and abrupt retouching, so that they are long and narrow and, although rare, characterize certain phases of the Solutrean period. Ouchtata bladelets are similar to the others, except that the retouched back is not uniform but irregular; this type of microlith characterizes certain periods of the Epipaleolithic Saharans. The Ibero-Maurusian and the Montbani bladelet, with a partial and irregular lateral retouching, is characteristic of the Italian Tardenoisian.[5]

Micro points

[edit]These are very sharp bladelets formed by abrupt retouching. There are a huge number of regional varieties of these microliths, nearly all of which are very hard to distinguish (especially those from the western area) without knowing the archaeological context in which they appear. The following is a small selection. Omitted are the foliaceous tips (also called leafed tips), which are characterized by a covering retouch and which constitute a group apart.[6]

- The Châtelperrón point is not a true microlith, although it is close to the required dimensions. Its antiquity and its short, curved blade edge make it the antecedent of many laminar microliths.

- The Micro-gravette or Gravette micro point is a microlith version of the Gravette point and is a narrow bladelet with an abrupt retouch, which gives it a characteristically sharp edge when compared to other types.

- The Azilian point links the Magdalenian microlith points with those from the western Epipaleolithic. They can be identified by a rough and invasive retouching.

- The Ahrensburgian point is also a peripheral paleolithic or western Epipaleolithic piece, but with a more specific morphology, as it is formed on a blade (not on a bladelet), is obliquely truncated and has a small tongue that possibly served as a haft on a spear point.

The next group contains a number of points from the Middle East characterized as cultural markers.

- The Emireh point from the Upper Paleolithic is almost the same as one found in Châtelperrón, which is likely to be contemporary, although they are slightly shorter and also appear to be fashioned from a blade and not a bladelet.

- The El-Wad point is from the end of the Upper Paleolithic from the same area, made from a very long, thin bladelet.

- The El-Khiam point has been identified by the Spanish archeologist González Echegaray in Protoneolithic sites in Jordan. They are little known but easy to identify by two basal notches, doubtless used as a haft.[7]

-

Châtelperrón points

-

Micro-gravette

-

Azilian point

-

Ahrensburguien point

-

El-Wad point

-

El-Khiam point

-

Adelaide point

-

Helwan points (Abu Salem points sub-type)

The Adelaide point is found in Australia. Its construction, based on truncations on a blade, has a nearly trapezoidal form. The Adelaide point emphasizes the range of variation in both time and culture of the laminar microliths; it also shows their technological differences, but sometimes morphological similarities, with geometric microliths. Laminar microliths can also sometimes be described as trapezoidal, triangular or lunate.[8] However, they are distinct from the geometric microliths because of the strokes used in the manufacture of geometric microliths, which mainly involved the microburin technique.

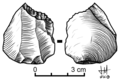

Geometric microliths

[edit]Geometric microliths are a clearly defined type of stone tool, at least in their basic forms. They can be divided into trapezoid, triangular and lunate (half-moon) forms, although there are many subdivisions of each of these types. A microburin is included among the illustrations below because, although it is not a geometrical microlith (or even a tool),[9] it is now seen as a characteristic waste product from the manufacture of these geometric microliths:

-

Microburin

-

Trapeze

-

Triangle

-

Lunate

Geometric microliths, though rare, are present as trapezoids in Northwest Africa in the Iberomaurusian. They later appear in Europe in the Magdalenian[10] initially as elongated triangles and later as trapezoids (although the microburin technique is seen from the Perigordian), they are mostly seen during the Epipaleolithic and the Neolithic. They remained in existence even into the Copper Age and Bronze Age, competing with "leafed" and then metallic arrowheads.

Microburin technique

[edit]All the currently known geometric microliths share the same fundamental characteristics – only their shapes vary. They were all made from blades or from microblades (nearly always of flint), using the microburin technique (which implies that it is not possible to conserve the remains of the heel or the conchoidal flakes from the blank). The pieces were then finished by a percussive retouching of the edges (generally leaving one side with the natural edge of the blank), giving the piece its definitive polygonal form. For example, in order to make a triangle, two adjacent notches were retouched, leaving free the third edge or base[4] (using the terminology of Fortea). They generally have one long axis and concave or convex edges, and it is possible for them to have a gibbosity (hump) or indentations. Triangular microliths may be isosceles, scalene or equilateral. In the case of trapezoid geometric microliths, on the other hand, the notches are not retouched, leaving a portion of the natural edge between them. Trapezoids can be further subdivided into symmetrical, asymmetrical and those with concave edges. Lunate microliths have the least diversity of all and may be either semicircular or segmental.

Archeological findings and the analysis of wear marks, or use-wear analysis, has shown that, predictably, the tips of spears, harpoons and other light projectiles of varying size received the most wear. Microliths were also used from the Neolithic on arrows, although a decline in this use coincided with the appearance of bifacial or "leafed" arrowheads that became widespread in the Chalcolithic period, or Copper Age (that is, stone arrowheads were increasingly made by a different technique during this later period).

Weapons and tools

[edit]Not all the different types of laminar microliths had functions that are clearly understood. It is likely that they contributed to the points of spears or light projectiles, and their small size suggests that they were fixed in some way to a shaft or handle.[11][12]

Backed edge bladelets are particularly abundant at a site in France that preserves habitation from the late Magdalenian – the Pincevent. In the remains of some of the hearths at this location, bladelets are found in groups of three, perhaps indicating that they were mounted in threes on their handles. A javelin tip made of horn has been found at this site with grooves made for flint bladelets that could have been secured using a resinous substance. Signs of much wear and tear have been found on some of these finds.[13]

Specialists have carried out lithic or microwear analysis on artefacts, but it has sometimes proved difficult to distinguish those fractures made during the process of fashioning the flint implement from those made during its use. Microliths found at Hengistbury Head in Dorset, England, show features that can be confused with chisel marks, but which might also have been produced when the tip hit a hard object and splintered.[14] Microliths from other locations have presented the same problems of interpretation.[15]

An exceptional piece of evidence for the use of microliths has been found in the excavations of the cave at Lascaux in the French Dordogne. Twenty backed edge bladelets were found with the remains of a resinous substance and the imprint of a circular handle (a horn). It appears that the bladelets might have been fixed in groups like the teeth of a harpoon or similar weapon.

In all these locations, the microliths found have been backed edge blades, tips and crude flakes. Despite the great number of geometric microliths that have been found in Western Europe, few examples show any clear evidence of their use, and all the examples are from the Mesolithic or Neolithic periods. Despite this, there is unanimity amongst researchers that these items were used to increase the penetrating potential of light projectiles such as harpoons, assegais, javelins and arrows.

Discoveries

[edit]Australia

[edit]The most common form of microliths found in Australia are backed artefacts. The earliest backed artefacts have been dated to the terminal Pleistocene, however they become increasingly common in Aboriginal Australian societies in the mid-Holocene, before declining in use and disappearing from the archaeological record approximately 1000 years before the British invasion of the continent in 1788.[16][17] The cause of this proliferation event is debated amongst archaeologists.[18][19][20]

Geographically they are found across almost all of continental Australia, except for the far north, but are particularly common in south-east Australia. Historically, backed artefacts were divided into asymmetrical Bondi points and symmetrical geometric microliths, however there appears to be no geographic or temporal pattern in the distribution of these shapes.[21][22] Backed artefact manufacturing workshops have been identified at Ngungara show significant variation in shape, which has been linked to the need to replace components of composite tools.[23]

Several studies in the production of backed artefacts have linked identified heat treatment as a key component as well as the use of large flank blanks.[24][25]

Functional studies of backed artefacts from south-eastern Australia show that they were multipurpose and multifunctional tools with a similar range of uses as unretouched flakes found at the same sites.[26][27] There is one unambiguous example of them being used as part of composite weapon, either a spear or a club, as 17 backed artefacts were found embedded into the skeleton of an adult male dated to approximately 4000 years BP in the Sydney suburb of Narrabeen.[28]

France

[edit]

In France, one unusual site stands out: the Mesolithic cemetery of Téviec, an island in Brittany. Numerous flint microliths were discovered here. They are believed to date to between 6740 and 5680 years BP - quite a long occupation. The end of the settlement came at the beginning of the Neolithic period.[29]

One of the skeletons that has been found has a geometric microlith lodged in one of its vertebra. All indications suggest that the person died because of this projectile; whether by intention or by accident is unknown. It is widely agreed that geometric microliths were mainly used in hunting and fishing, but they may also have been used as weapons.[30]

Scandinavia

[edit]Well-preserved examples of arrows with microliths in Scandinavia have been found at Loshult, at Osby in Sweden, and Tværmose, at Vinderup in Denmark. These finds, which have been preserved practically intact due to the special conditions of the peat bogs, have included wooden arrows with microliths attached to the tip by resinous substances and cords.

According to radiocarbon measurements, the Loshult arrows are dated to around 8000 BC, which represents a middle part of the Maglemose culture. This is close to the Early Boreal/Late Boreal transition.[31]

England

[edit]There are many examples of possible tools from Mesolithic deposits in England. Possibly the best known is a microlith from Star Carr in Yorkshire that retains residues of resin, probably used to fix it to the tip of a projectile. Recent excavations have found other examples. Archeologists at the Risby Warren V site in Lincolnshire have uncovered a row of eight triangular microliths that are equidistantly aligned along a dark stain indicating organic remains (possibly the wood from an arrow shaft). Another clear indication is from the Readycon Dene site in West Yorkshire, where 35 microliths appear to be associated with a single projectile. In Urra Moor, North Yorkshire, 25 microliths give the appearance of being related to one another, due to the extreme regularity and symmetry of their arrangement in the ground.[32]

The study of English and European artifacts in general has revealed that projectiles were made with a widely variable number of microliths: in Tværmose there was only one, in Loshult there were two (one for the tip and the other as a fin),[33] in White Hassocks, in West Yorkshire, more than 40 have been found together; the average is between 6 and 18 pieces for each projectile.[32]

India

[edit]Early research regard the microlithic industry in India as a Holocene phenomenon, however a new research provides solid data to put the South Asia microliths industry up to 45 ka across whole South Asia subcontinent. This new research also synthesizes the data from genetic, paleoenvironmental and archaeological research, and proposes that the emergence of microlith in India subcontinent could reflect the increase of population and adaptation of environmental deterioration.[34][35][36]

Sri Lanka

[edit]In 1968 human burials sites were uncovered inside the Fa Hien Cave in Sri Lanka. A further excavation in 1988 yielded microlith stone tools, remnants of prehistoric fireplaces and organic material, such as floral and human remains. Radiocarbon dating indicates that the cave had been occupied from about 33,000 years ago, the Late Pleistocene and Mesolithic to 4,750 years ago, the Neolithic in the Middle Holocene. Human remains of the several sediment deposits were analyzed at Cornell University and studied by Kenneth A. R. Kennedy and graduate student Joanne L. Zahorsky. Sri Lanka has yielded the earliest known microliths, which did not appear in Europe until the Early Holocene.[37][38] 2019 study found Fa-Hien Lena cave microlith assemblage represents the earliest microlith assemblage in South Asia dating back to c. 48,000–45,000 years ago.[36]

Dating

[edit]

Laminar microliths are common artifacts from the Upper Paleolithic and the Epipaleolithic, to such a degree that numerous studies have used them as markers to date different phases of prehistoric cultures.

During the Epipaleolithic and the Mesolithic, the presence of laminar or geometric microliths serves to date the deposits of different cultural traditions. For instance, in the Atlas Mountains of northwest Africa, the end of the Upper Paleolithic period coincides with the end of the Aterian tradition of producing laminar microliths, and deposits can be dated by the presence or absence of these artifacts. In the Near East, the laminar microliths of the Kebarian culture were superseded by the geometric microliths of the Natufian tradition a little more than 11,000 years ago. This pattern is repeated throughout the Mediterranean basin and across Europe in general.[4][39]

A similar thing is found in England, where the preponderance of elongated microliths, as opposed to other frequently occurring forms, has permitted the Mesolithic to be separated into two phases: the Earlier Mesolithic of about 8300–6700 BCE, or the ancient and laminar Mesolithic, and the Later Mesolithic, or the recent and geometric Mesolithic. Deposits can be thus dated based upon the assemblage of artifacts found.[40]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Groman-Yaroslavski, Iris; Chen, Hong; Liu, Cheng; Shimelmitz, Ron; Yeshurun, Reuven; Liu, Jiying; Yang, Xia; Nadel, Dani (2020-06-03). Petraglia, Michael D. (ed.). "Versatile use of microliths as a technological advantage in the miniaturization of Late Pleistocene toolkits: The case study of Neve David, Israel". PLOS ONE. 15 (6): e0233340. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1533340G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233340. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7269238. PMID 32492038.

- ^ Piel-Desruisseaux, Jean-Luc (1986). Outils préhistoriques. Forme. Fabrication. Utilisation. Paris: Masson. pp. 147–149. ISBN 2-225-80847-3.

- ^ Pelegrin, Jacques (1988). Débitage expérimental par pression. Du plus petit au plus grand. Vol. Journée d'études technologiques en Préhistoire. Technologie préhistorique. pp. 37–53. ISBN 2-222-04235-6.

- ^ a b c Fortea Pérez; Francisco Javier (1973). Los complejos microlaminares y geométricos del Epipaleolítico mediterráneo español. Universidad de Salamanca. ISBN 84-600-5678-3.

- ^ Brézillon, Michel (1971). La dénomination des objets de pierre taillée. París: Editions du CNRS. pp. 263–267.

- ^ Brézillon, Michel (1971). La dénomination des objets de pierre taillée. París: Editions du CNRS. pp. 292–340.

- ^ González Echegaray, J. (1964). Excavaciones en la terraza de El Khiam (Jordania). Bibliotheca Praehistorica Hispana.

- ^ Geometric shapes, as we have seen, are present in many laminar microliths: for example the Dufour bladelet is an elongated lunate shape, the El-Emireh point is a triangle and the Adelaide point is a trapeze, the El-Wad point is spindle shaped; and there are many other examples.

- ^ Some of the earlier researchers, such as Octobon Octobon, E. (1920). "La question tardenoisienne. Montbani". Revue Anthropologique. p. 107.), Peyrony and Noone (Peyrony, D. y Noone H. V. V. (1938). "Usage possible des microburins". 2 (numéro 3). Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help), believed that these microburins had a useful function. Currently it has been demonstrated that these microburins did not have a function, at least not intentionally, although it cannot be ruled out that they were not reused at some point. - ^ Bordes, F. y Fitte, P. (1964). "Microlithes du Magdalénien supérieur de la Gare de Gouze (Dordogne)". Miscelánea en homenaje al Abate Henri Breuil. Vol. I. Barcelona. p. 264.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Laming-Emperaire, Annette (1980). "Los cazadores depredadores del posglacial y del Mesolítico". La Prehistoria. Editorial Labor, Barcelona. p. 68. ISBN 84-335-9309-9.

- ^ Piel-Desruisseaux, Jean-Luc (1986). Outils préhistoriques. Forme. Fabrication. Utilisation. Masson, Paris. pp. 123–127. ISBN 2-225-80847-3.

- ^ Caspar, Jean-Paul; De Bie, Marc (1996). "Preparing for the Hunt in the Late Paleolithic Camp at Reken, Belgium". Journal of Field Archaeology. 23 (4): 437–460. doi:10.1179/009346996791973747.

- ^ Barton, R. N. E. y Bergman, C. A. (1982). "Hunters at Hengistbury: some evidence from experimental archaeology". World Archaeology. 14 (2): 237–248. doi:10.1080/00438243.1982.9979864. ISSN 0043-8243.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ M. Lenoir has found knapping similar to that used in chiseled bladelets from Gironde, but considered this to be a coincidence and attributed the marks to the fact that the microliths were mounted on the tip of a projectile. A similar line of enquiry has also been followed by Lawrence H. Keeley, who has studied a wide range of bladelets from the French site at Buisson Campin, in Verberie, Oise.

- ^ Slack, Michael J.; Fullagar, Richard L.K.; Field, Judith H.; Border, Andrew (October 2004). "New Pleistocene ages for backed artefact technology in Australia". Archaeology in Oceania. 39 (3): 131–137. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.2004.tb00569.x.

- ^ Hiscock, Peter; Attenbrow, Val (July 2004). "A revised sequence of backed artefact production at Capertee 3, New South Wales". Archaeology in Oceania. 39 (2): 94–99. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.2004.tb00566.x.

- ^ Attenbrow, Val; Robertson, Gail; Hiscock, Peter (2009-12-01). "The changing abundance of backed artefacts in south-eastern Australia: a response to Holocene climate change?". Journal of Archaeological Science. 36 (12): 2765–2770. Bibcode:2009JArSc..36.2765A. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2009.08.018. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ Hiscock, Peter (2008-06-28). "Pattern and Context in the Holocene Proliferation of Backed Artifacts in Australia". Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association. 12 (1): 163–177. doi:10.1525/ap3a.2002.12.1.163.

- ^ White, Peter; Bowdler, Sandra; Kuhn, Steven; McNiven, Ian; Shott, Michael; Veth, Peter; White, Peter (2011-06-01). "Forum: Backed Artefacts: Useful Socially and Operationally". Australian Archaeology. 72 (1): 67–75. doi:10.1080/03122417.2011.11690534. ISSN 0312-2417.

- ^ Hiscock, Peter (2014-12-01). "Geographical variation in Australian backed artefacts: Trialling a new index of symmetry". Australian Archaeology. 79 (1): 124–130. doi:10.1080/03122417.2014.11682028. ISSN 0312-2417.

- ^ Mcdonald, Jo; Reynen, Wendy; Fullagar, Richard (October 2018). "Testing predictions for symmetry, variability and chronology of backed artefact production in Australia's Western Desert". Archaeology in Oceania. 53 (3): 179–190. doi:10.1002/arco.5162. ISSN 0728-4896.

- ^ Way, Amy Mosig; Koungoulos, Loukas; Wyatt-Spratt, Simon; Hiscock, Peter (2023-04-26). "Investigating hafting and composite tool repair as factors creating variability in backed artefacts: Evidence from Ngungara (Weereewa/Lake George), south-eastern Australia". Archaeology in Oceania. 58 (2): 214–222. doi:10.1002/arco.5292. hdl:10072/428642. ISSN 0728-4896.

- ^ Hiscock, Peter (July 1993). "Bondaian Technology in the Hunter Valley, New South Wales". Archaeology in Oceania. 28 (2): 65–76. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.1993.tb00317.x. hdl:1885/41387.

- ^ White, Beth (2012-12-01). "Minimum Analytical Nodules and lithic activities at site W2, Hunter Valley, New South Wales". Australian Archaeology. 75 (1): 25–36. doi:10.1080/03122417.2012.11681947. ISSN 0312-2417.

- ^ Robertson, Gail; Attenbrow, Val; Hiscock, Peter (June 2009). "Multiple uses for Australian backed artefacts". Antiquity. 83 (320): 296–308. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00098446. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ^ Robertson, Gail; Attenbrow, Val; Hiscock, Peter (July 2019). "Residue and use-wear analysis of non-backed retouched artefacts from Deep Creek Shelter, Sydney Basin: Implications for the role of backed artefacts". Archaeology in Oceania. 54 (2): 73–89. doi:10.1002/arco.5177. ISSN 0728-4896.

- ^ McDonald, Josephine J.; Donlon, Denise; Field, Judith H.; Fullagar, Richard L. K.; Coltrain, Joan Brenner; Mitchell, Peter; Rawson, Mark (December 2007). "The first archaeological evidence for death by spearing in Australia". Antiquity. 81 (314): 877–885. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00095971. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ^ Schulting, R.J. (1999) - "Nouvelles dates AMS à Téviec et Hoëdic (Quiberon, Morbihan)", Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, issue 96, number 2, pp. 203–207.

- ^ Piel-Desruisseaux, Jean-Luc (1986). Outils préhistoriques. Forme. Fabrication. Utilisation. Masson, Paris. pp. 147–149. ISBN 2-225-80847-3.

- ^ Lars Larsson (2018), The Loshult Arrows: Cultural Relations and Chronology academia.edu

- ^ a b Myers, Andrew (1989). "Reliable and mantainable technological strategies in the Mesolithic of mainland Britain". Time, energy and stone tools: New directions in Archaeology (edited by Robin Torrence). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 78–91. ISBN 0-521-25350-0.

- ^ Petersson, M. (1951). Microlithen als Pfeilspitzen. Ein Fund aus dem Lilla-Loshult Moor: Ksp. Loshult, Skane. Historika Museum. (Pagies 123–137.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Petraglia; et al. (2009). "Population increase and environmental deterioration correspond with microlithic innovations in South Asia ca. 35,000 years ago" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (30): 12261–12266. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10612261P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810842106. PMC 2718386. PMID 19620737.

- ^ Malik, S. C. (1966). "The Late Stone Age Industries from Excavated Sites in Gujarat, India". Artibus Asiae. 28 (2/3): 162–174. doi:10.2307/3249352. JSTOR 3249352.

- ^ a b Wedage, Oshan; Picin, Andrea; Blinkhorn, James; Douka, Katerina; Deraniyagala, Siran; Kourampas, Nikos; Perera, Nimal; Simpson, Ian; Boivin, Nicole; Petraglia, Michael; Roberts, Patrick (2 October 2019). "Microliths in the South Asian rainforest ~45-4 ka: New insights from Fa-Hien Lena Cave, Sri Lanka". PLOS ONE. 14 (10): e0222606. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1422606W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222606. hdl:10072/412746. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6774521. PMID 31577796.

- ^ "The Travels of Pahiyangala". Archived from the original on 2006-09-27.

- ^ "Pre- and Protohistoric Settlement in Sri Lanka". www.lankalibrary.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ Professor Fortea has been able to distinguish two traditions in the Epipaleolithic period based in the Spanish Mediterranean , the "Microlaminar Complex" (with three separate phases: that of Sant Grégori de Falset, that based on the Cova de Les Mallaetes in Valencia and that of the Epigravettian) and the "Geometric Complex" (with two phases: the Filador and the Cocina, which receive their names from caves located on the eastern coast of Spain).

- ^ Myers, Andrew (1989). "Reliable and mantainable technological strategies in the Mesolithic of mainland Britain". In Robin Torrence (ed.). Time, energy and stone tools: New directions in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-521-25350-0. The same author has suggested that the geometric microliths may replace one or two rows of teeth in the bone harpoons commonly found in the Upper Paleolithic at the end of the Upper Magdalanian (page 84).

External links

[edit] Media related to Microliths at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Microliths at Wikimedia Commons