Influenza A virus subtype H2N2

| Influenza A virus subtype H2N2 | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Insthoviricetes |

| Order: | Articulavirales |

| Family: | Orthomyxoviridae |

| Genus: | Alphainfluenzavirus |

| Species: | |

| Serotype: | Influenza A virus subtype H2N2

|

| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

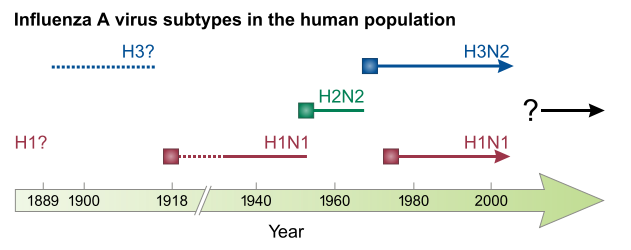

Influenza A virus subtype H2N2 (A/H2N2) is a subtype of Influenza A virus. H2N2 has mutated into various strains including the "Asian flu" strain (now extinct in the wild), H3N2, and various strains found in birds. It is also suspected of causing a human pandemic in 1889.[1][2] The geographic spreading of the 1889 Russian flu has been studied and published.[3]

Russian flu

[edit]Some believe that the 1889–1890 Russian flu was caused by the influenzavirus A virus subtype H2N2, but the evidence is not conclusive. It is the earliest flu pandemic for which detailed records are available.[4] More recently, there are speculations that it might have been caused by one of the coronaviruses first discovered in the 1960s.[5]

Asian flu

[edit]The "Asian Flu" was a category 2 flu pandemic outbreak of influenzavirus A that first appeared in Guizhou, China in early 1957 and lasted until 1958.[6] The first cases were reported in Singapore in February 1957. In February 1957, a new influenza A (H2N2) virus emerged in East Asia, triggering a pandemic (“Asian Flu”). This H2N2 virus was composed of three different genes from an H2N2 virus that originated from an avian influenza A virus, including the H2 hemagglutinin and the N2 neuraminidase genes. It was first reported in Singapore in February 1957, Hong Kong in April 1957, and in coastal cities in the United States in summer 1957. Some authors believe it originated from mutation in wild ducks combining with a pre-existing human strain.[7] Other authors are less certain.[8] It reached Hong Kong by April, and US by June. Estimates of US and worldwide deaths caused by this pandemic varies widely depending on source; ranging from approximately 69,800[7] to 116,000 in the United States,[9] and worldwide from 1 million to 4 million, with the World Health Organization (WHO) settling on "about 2 million," with an overall mortality rate of 0.6%.[10] Asian Flu was of the H2N2 subtype (a notation that refers to the configuration of the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins in the virus) of type A influenza, and an influenza vaccine was developed in 1957 to contain its outbreak.[citation needed]

The Asian Flu strain later evolved via antigenic shift into H3N2 which caused a milder pandemic from 1968 to 1969.[11]

Both the H2N2 and H3N2 pandemic strains contained avian influenza virus RNA segments.[12]

Test kits

[edit]From October 2004 to February 2005, approximately 3,700 test kits of the 1957 H2N2 virus were accidentally spread around the world from the College of American Pathologists (CAP). CAP assists laboratories in accuracy by providing unidentified samples of viruses; private contractor Meridian Bioscience in Cincinnati, U.S., chose the 1957 strain instead of one of the less deadly avian influenza virus subtypes.[13] The 1957 H2N2 virus is considered deadly and the U.S. government called for the vials containing the strain to be destroyed.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ Hilleman, Maurice R. (2002). "Realities and enigmas of human viral influenza: pathogenesis, epidemiology and control". Vaccine. 20 (25–26): 3068–3087. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.523.7697. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00254-2. PMID 12163258.

- ^ "The Influenza H5N1 Report". Pliva.com. April 2, 1998. Archived from the original on 24 October 2004.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Alexis Madrigal (April 26, 2010). "1889 Pandemic Didn't Need Planes to Circle Globe in 4 Months". Wired. Wired Science. Archived from the original on April 29, 2010. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ "Encarta on influenza". Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ^ Anthony King: What four coronaviruses from history can tell us about covid-19, on: New Scientist, 29 April 2020

- ^ Pennington, T H (2006). "A slippery disease: a microbiologist's view". BMJ. 332 (7544): 789–790. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7544.789. PMC 1420718. PMID 16575087.

- ^ a b Green, Jeffrey (2006). The Bird Flu Pandemic. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0312360568.

- ^ Belshe, Robert B. (2005-11-24). "The Origins of Pandemic Influenza — Lessons from the 1918 Virus". New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (21): 2209–2211. doi:10.1056/NEJMp058281. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 16306515.

- ^ "1957-1958 Pandemic (H2N2 virus)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 22 January 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Lovelace Jr., Berkeley (26 March 2020). "The coronavirus may be deadlier than the 1918 flu: Here's how it stacks up to other pandemics". CNBC. f NBCUniversal. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Starling, Arthur E. (2006). Plague, SARS, and the story of medicine in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-805-3. OCLC 68909495.

- ^ Chapter Two : Avian Influenza by Timm C. Harder and Ortrud Werner Archived 2017-08-09 at the Wayback Machine from free on-line Book called Influenza Report 2006 which is a medical textbook that provides a comprehensive overview of epidemic and pandemic influenza.

- ^ Roos, Robert (April 13, 2005). "Vendor thought H2N2 virus was safe, officials say". CIDRAP. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Pandemic preparedness: lessons learnt from H2N2 and H9N2 candidate vaccines

- Interim CDC-NIH Recommendation for Raising the Biosafety Level for Laboratory Work Involving Noncontemporary Human Influenza Viruses at the Wayback Machine (archived 6 March 2016)

- New Scientist: Bird Flu

- Pandemic-causing 'Asian flu' accidentally released

- Persistence of Q strain of H2N2 influenza virus in avian species: antigenic, biological and genetic analysis of avian and human H2N2 viruses

External links

[edit]- Influenza Research Database Database of influenza sequences and related information.