Hinkley Point C nuclear power station

| Hinkley Point C nuclear power station | |

|---|---|

The headland at Hinkley Point with the current power stations visible in the background | |

| |

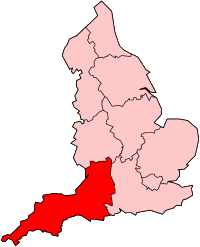

| Country | England, United Kingdom |

| Location | Somerset, South West England |

| Coordinates | 51°12′22″N 3°08′34″W / 51.2061°N 3.1429°W |

| Status | Approved |

| Construction cost | £18bn[1] |

| Owner | EDF Energy |

| Operator | Expected NNB Generation Company |

| Nuclear power station | |

| Reactor type | EPR |

| Reactor supplier | Areva |

| Thermal capacity | 4,500 MWt |

| Power generation | |

| Make and model | Alstom |

| Units planned | 2 × 1,600 MWe |

| Nameplate capacity | 3,200 MW |

| External links | |

| Website | www |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

Strike price = £92.50/MWh[2][3] | |

Hinkley Point C nuclear power station is a project to construct a 3,200 MWe nuclear power station with two EPR reactors in Somerset, England.[4] The site is one of eight announced by the British government in 2010,[5] and on 26 November 2012 a nuclear site licence was granted.[6] In October 2014, the European Commission adjusted the "gain-share mechanism" so that the project does not break state-aid rules.[7] Financing for the project will be provided "by the mainly state-owned EDF [and] state-owned CGN will pay £6bn for one third of it".[8] EDF may sell up to 15% of their stake.[8]

History

In January 2008, the UK government gave the go-ahead for a new generation of nuclear power stations to be built.[9] Hinkley Point C, in conjunction with Sizewell C, was expected to contribute 13% of UK electricity by the early 2020s.[10][11] Areva, the EPR's designer, initially estimated that electricity could be produced at the competitive price of £24 per MWh.[12]

EDF, which is 85% owned by the French government,[13] purchased British Energy, now EDF Energy Nuclear Generation Ltd, for £12.4 billion in a deal that was finalised in February 2009. This deal was part of a joint venture with UK utility Centrica, who acquired a 20% stake in EDF Energy Nuclear Generation Ltd as well as the option to participate in EDF Energy's UK new nuclear build programme.

In September 2008, EDF, the new owners of Hinkley Point B, announced plans to build a third, twin-unit European Pressurised Reactor (as the EPR was then called) reactor at Hinkley Point,[10] to join Hinkley Point A (Magnox), which is now closed and being decommissioned, and the Hinkley Point B (AGR), which has a closure date for accounting purposes of 2023[14] but is likely to be closed much later.[15]

On 18 October 2010, the British government announced that Hinkley Point – already the site of the disused Hinkley Point A and the still operational Hinkley Point B power stations – was one of the eight sites it considered suitable for future nuclear power stations.[5] NNB Generation Company, a subsidiary of EDF, submitted an application for development consent to the Infrastructure Planning Commission on 31 October 2011.[16] In October 2013, the government announced that it had approved subsidized feed-in prices for the electricity production of Hinkley Point C., with the plant expected to be completed in 2023 and remain operational for 60 years.[2]

In 2011, Elizabeth Gass sold some 230 acres of her Fairfield estate at Hinkley Point for about £50 million. There are conflicting reports about whether the land was for the development of nuclear power or a wind farm.[17][18]

A protest group, Stop Hinkley, was formed to campaign for the closure of Hinkley Point B and oppose any expansion at the Hinkley Point site. In October 2011, more than 200 protesters blockaded the site. In December 2013, the European Commission opened an investigation to assess whether the project breaks state-aid rules [19][20] with reports suggesting the government's plan may well constitute illegal state aid.[21][22][23]

In February 2013, Centrica withdrew from the new nuclear construction programme, citing building costs that were higher than it had anticipated, caused by larger generators at Hinkley Point C, and a longer construction timescale, caused by modifications added after the Fukushima disaster.[24]

In March 2013 a group of MPs and academics, concerned that the 'talks lack the necessary democratic accountability, fiscal and regulatory checks and balances', called for the National Audit Office to conduct a detailed review of the negotiations between the Department of Energy and Climate Change and EDF.[25]

In December 2013, the European Commission opened an investigation to assess whether the project breaks state-aid rules. Joaquín Almunia, the EU Competition Commissioner, referred to the plans as "a complex measure of an unprecedented nature and scale"[20] and said that the European Commission is not "not under any legal time pressure to complete the investigation".[26] In January 2014, an initial critical report was published, indicating the government's plan may well constitute illegal state aid, requiring a formal state aid investigation examining the subsidies.[21] David Howarth, a former Liberal Democrat MP, doubted "whether this is a valid contract at all" under EU and English Law.[22] Franz Leidenmuhler (University of Linz, a specialist in EU state aid cases and European competition law, wrote that "a rejection is nearly unavoidable. The Statement of the Commission in its first findings of December 18, 2013, is too clear. I do not think that some conditions could change that clear result."[23]

In March 2014, the Court of Appeal allowed An Taisce, the National Trust for Ireland, to challenge the legality of decision by the Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change to grant development consent. An Taisce lawyers say there was a failure to undertake "transboundary consultation" as required by the European Commission’s Environmental Impact Assessment Directive. Lord Justice Sullivan said that "he did not venture that it had a real prospect of success, it was desirable that the court should give a definitive view as to whether there should be a reference to the Court of Justice of the European Union and, if not, on the meaning of the Directive".[27] In July 2014 the Court of Appeal rejected An Taisce's application on the basis 'that severe nuclear accidents were very unlikely... no matter how low the threshold for a "likely" significant effect on the environment... the likelihood of a nuclear accident was so low that it could be ruled out even applying the stricter Waddenzee approach' [28]

The UN, under the Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context, ordered the Department for Communities and Local Government to send a delegation to face the committee in December 2014, on the "profound suspicion" that the UK failed to properly consult neighbouring countries.[29]

On 22 September 2014, news leaked that "discussions with the UK authorities have led to an agreement. On this basis, vice-president Almunia will propose to the college of commissioners to take a positive decision in this case. In principle a decision should be taken within this mandate" with a final decision expected in October 2014.[11]

On 8 October 2014 it was announced that the European Commission had approved the project, with an overwhelming majority and only four commissioners voting against the decision.[7] The European Commission adjusted the "gain-share mechanism" whereby higher profits are shared with UK taxpayers.[7]

In June 2015, the Austrian government filed a legal complaint with the European Commission on the subject of the state subsidies.[30]

In September 2015, EDF admitted that the project will not complete in 2023, with a further announcement on the final investment decision expected in October 2015. Earlier plans to announce Areva and 'other investors' have been dropped: "in order to have speed, in the first phase EDF and the Chinese will be the investors".[31] A report by the IEA and NEA suggests privatization as one of the causes for British nuclear power being more expensive than nuclear power in other countries.[32][33]

In February 2016 EDF again failed to make a final decision on proceeding with the project, disclosing that the financial agreement with CGN was yet to be confirmed. EDF, which had recently reported a 68% fall in net profit, was still looking at how it would finance its share of the project. With EDF's share price having halved over the preceding year, the cost of the Hinkley Point C project now exceeded the entire market capitalisation of EDF. EDF stated that "first concrete", the start of actual construction, was not planned to begin until 2019.[34][35]

Permits and licences

On 26 November 2012, it was announced that the UK Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) had awarded a nuclear site licence to NNB Generation Company, a subsidiary created by EDF Energy.[6] This was the first nuclear site licence awarded for a nuclear power station in the UK since 1987, when one was granted for the construction of Sizewell B in Suffolk.[6]

In March 2013, three environmental permits setting levels for emissions from the proposed power station were granted.[36]

Throughout 2013 the operator has been in negotiations with the Department of Energy and Climate Change and other government agencies. A major sticking point has been a demand by EDF Energy for a guaranteed price for the electricity to be produced, which was about twice the current UK electricity rates. The project is part of the UK's plans to implement a fifty per cent cut in greenhouse gas emissions by the mid-2020s, which provide for building this and several other nuclear power plants. By 2013, the operator had invested about £1 billion in site preparation and other start-up costs. If built, the plant will produce about 7% of the UK's electricity needs.[37] Total installation costs are supposed to be £14 billion.

On 19 March 2013, planning consent was given, but agreement on electricity pricing was still required before building could start.[38]

On 21 October 2013, the government announced that it had approved the agreement of a strike price for the plant's electricity, a major condition for its construction.[2][3]

Economics

The unhedged UK wholesale electricity price in January 2015 was about £50/MWh.[39] EDF has negotiated a guaranteed fixed price – a "strike price" – for electricity from Hinkley Point C of £92.50/MWh (in 2012 prices),[2][3][40] which will be adjusted (linked to inflation) during the construction period and over the subsequent 35 years tariff period. The price could fall to £89.50/MWh if a new plant at Sizewell is also approved.[2][3] Research carried out by Imperial College Business School argues that no new nuclear power plants would be built in the UK without government intervention.[41]

However, nuclear energy should also be compared with the strike prices guaranteed for other power generation sources in the UK. In 2012, maximum strike prices were £55/MWh for landfill gas, £75/MWh for sewage gas, £95/MWh for onshore wind power, £100/MWh for hydroelectricity, £120/MWh for photovoltaic power stations, £145/MWh for geothermal and £155/MWh for offshore wind farms.[42] In 2015, actual strike prices were in the range £50-£79.23/MWh for photovoltaic, £80/MWh for energy from waste, £79.23-£82.5/MWh for onshore wind, and £114.39-£119.89/MWh for offshore wind and conversion technologies (all expressed in 2012 prices).[43] These prices are indexed to inflation.[44] For projects commissioned in 2018–2019, maximum strike prices are set to decline by £5/MWh for geothermal and onshore wind power, and by £15/MW for offshore wind projects and large-scale photovoltaic, while hydro power remains unchanged at £100/MWh.[45] The strike price is agreed in 'a contract between the generator and a new Government-owned counterparty'[40] and guarantees the price per MWh paid to the electricity producer. The strike price is not the same as the Levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) which is a first order estimate of the average cost the producer must receive to break-even.

Jim Ratcliffe, the chairman and chief executive officer of the Ineos chemicals group, recently agreed a deal for nuclear power in France at £37.94 (45 Euros) per MWh. He said of the Hinkley Point C deal: 'Forget it. Nobody in manufacturing is going to go near £95 per MWh'.[46] Similarly, the Finnish company Fennovoima has signed a contract with the Russian company Rosatom to build a 1200 MW greenfield nuclear power plant, Hanhikivi, in Pyhäjoki in northern Finland. The Finnish project is estimated to 'deliver electricity at "no more than €50 (£41) per megawatt-hour"' with planned completion in 2024.[47]

Return on Equity

One analyst at Liberium Capital[48] described the strike price as 'economically insane': "as far as we can see this makes Hinkley Point the most expensive power station in the world... on a leveraged basis we expect EDF to earn a Return on Equity (ROE) well in excess of 20% and possibly as high as 35%.

"Having considered the known terms of the deal, we are flabbergasted that the UK Government has committed future generations of consumers to the costs that will flow from this deal".[49] According to Policy Connect, ROE could be between around 19 and 21%, with "broadly two possible reasons...firstly, the risks faced by EDF could genuinely be greater, therefore commanding a higher rate of return. Alternatively, or in addition, the negotiating process may not have been effective in driving down the expected rate of return relative to risk. A lack of competition in the negotiating process could have been influential here. The European Commission has questioned the likelihood of the first of these explanations, in light of what is already known about the allocation of risk". [50]

The European Commission decision on 8 October 2014 adjusted the "gain-share mechanism" whereby higher profits are shared with UK taxpayers. Rather than a 50-50 profit share if the project returned above 15%, the revised "gain share mechanism" will see the UK taxpayer get 60 per cent of any profits above a 13.5% return.[7]

Financing

The construction cost was given by EDF as £16 billion in 2012,[51] updated to £18 billion in 2015.[1] The European Commission has previously estimated £24.5 billion, including financing costs during construction.[1]

EDF has been facing 'lengthy delays and steep cost overruns' on an EPR nuclear plant that it is building at Flamanville [52] in France. Areva has similar problems with budget overrun and schedule at its EPR nuclear plant project at Olkiluoto in Finland, leading France's energy minister to say that 'an overhaul of the country’s state-controlled nuclear energy industry was imminent' [52] and for EDF to say a decision on Hinkley Point C 'might not be made any time soon'.[52] Finland has cancelled its fourth EPR nuclear power plant project at Olkiluoto[53] opting, instead, for a VVER-1200/V-491 reactor estimated to cost 'less than €50/MWh (5 cents/kWh), including all production costs, depreciation, finance costs and waste management'.[54]

Delays with financing have been attributed, among other things, to problems with the cooling system design at Flamanville. As of 21 September 2015 the project continued to have the support of the British government which issued a £2 billion government guarantee for financing of the project.[55]

In 2016 EDF and was still looking at how it would finance its share of the project. EDF had reported a 68% fall in net profit, and its market value halved over the preceding year to €19.5 billion, while carrying a net debt of €37 billion. The cost of the Hinkley Point C project now exceeded the entire market capitalisation of EDF.[34][56]

EPR

EDF plans to use two of Areva's EPR design, with a design net power output each of 1,600 MWe (1,630 MWe gross).[57][58] The four commercial EPR units currently being built are: one at Olkiluoto Nuclear Power Plant in Finland, one at Flamanville Nuclear Power Plant in France, and further two, Taishan 1 & 2, in China.[10] These reactors were meant to lead a nuclear renaissance, but have been substantially delayed and are running over-budget.[59][60][61]

The Union of Concerned Scientists has referred to the EPR as the only new reactor design under consideration in the United States that "...appears to have the potential to be significantly safer and more secure against attack than today's reactors.".[62] However, George Monbiot, a vocal supporter of nuclear power, says that "the clunky third-generation power station chosen for Hinkley C already looks outdated, beside the promise of integral fast reactors and liquid fluoride thorium reactors. While other power stations are consuming nuclear waste (spent fuel), Hinkley will be producing it." [63]

The EPR design can use 5% enriched uranium oxide fuel, optionally with up to 50% mixed uranium plutonium oxide fuel,[64] which is a fuel that partly recycles/consumes constituents of spent fuel produced by other reactors. The EPR is the evolutionary descendant of the Framatome N4 and Siemens Power Generation Division KONVOI reactors.[65]

Public opinion

In July 2012, a YouGov poll reported that 63% of UK respondents agreed that nuclear generation should be part of the country's energy mix, up from 61% in 2010. Opposition fell to 11%.[66]

In February 2013, a poll published by Ipsos MORI which queried 1046 British individuals determined that support for new nuclear generation capacity was at 42% of the population. With the proportion of the population opposed to new nuclear generation being reported as unchanged at 20%, close to the lowest recorded proportion, by the agency in 2010, of 19% opposed. The results also report that the proportion of the population that was undecided or neutral had increased, and it stood at 38%.[67]

In 2013 a survey by Harris Interactive of more than 2000 UK respondents found that 'one in four people (24%) considered nuclear power to offer the greatest potential' alongside solar (23%) and ahead of wind power (18%). Immediately following the announcement of the agreement between EDF and the government, 35% considered it to be a positive step, 21% felt it was a negative development and 28% were indifferent.[68]

Organised opposition

A protest group, Stop Hinkley, was formed to campaign for the closure of Hinkley Point B and oppose any expansion at the Hinkley Point site or elsewhere in the Bristol Channel and Severn Estuary. The group is reportedly concerned that the new generation of power stations will store nuclear waste on site until a permanent repository is found – claiming this is an unknown length of time and, could potentially take decades.[69] The group issued a press release opposing any plans for a new power station on 24 September 2008, when it was announced that EDF had offered to acquire British Energy, the protest group has acknowledged that opposition in the local area is by no means unanimous.[70]

In October 2011, more than 200 protesters blockaded the site. Members of several anti-nuclear groups that are part of the Stop New Nuclear alliance barred access to Hinkley Point power station in protest at EDF Energy's plans to renew the site with two new reactors.[71]

In February 2012, about seven protesters set up camp in an abandoned farmhouse on the site of the proposed Hinkley Point C nuclear power station. They were reportedly angry that "West Somerset Council has given EDF Energy the go-ahead for preparatory work before planning permission has been granted". The group also claimed that a nature reserve is at risk from the proposals.[72]

On 10 March 2012, the first anniversary of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, two hundred anti-nuclear campaigners formed a symbolic chain around Hinkley Point to voice their opposition to new nuclear power plants, and to call on the coalition government to hold back on its plan for seven other new nuclear plants across the UK. The human chain was planned to continue for 24 hours, with the activists blocking the main Hinkley Point entrance.[73]

In Germany, the renewable energy supplier Elektrizitätswerke Schönau (EWS) lodged a formal complaint on 28 November 2014, on the basis that the project 'breaches Article 107 TFEU by approving distortive state aids'.[74] EWS have also launched an online petition, with about 168,000 supporters by June 2015.[75]

Construction work

During 2014, while awaiting the final decisions about whether the project will go ahead, 400 staff had been undertaking initial preparation and construction work. This work included access roads and roundabouts for increased construction traffic, park and ride schemes for the site workers, and a new roundabout for the village of Cannington. Further plans include the construction of a sea wall and a jetty for ships to deliver sand, aggregate and cement for concrete production.[76]

Timeline

- March 2008 UK and France announce deal to construct new nuclear power stations

- September 2008 EDF buys British Energy

- May 2009 Centrica announces joint venture with EDF to build new nuclear power stations in UK

- October 2010 Hinkley Point announced as one of the eight candidates by the British government

- April 2011 Health and Safety Executive and Environment Agency delay assessment of proposed reactor designs due to Fukushima disaster

- October 2011 Application for development consent by NNB Generation Company was submitted to the Infrastructure Planning Commission

- November 2012 EDF awarded nuclear site licence

- February 2013 Centrica pulls out of joint venture with EDF

- March 2013 EDF granted development consent order from Department for Energy and Climate Change

- October 2013 Government and EDF agree on "strike price" of Hinkley Point C

- October 2014 European Commission announced that it has approved the Hinkley Point C State aid case.

- September 2015, EDF admitted that the project will not complete in 2023, with a further announcement on the final investment decision expected in October 2015.

- 21 September 2015, Government announces £2 billion loan guarantee for the project[77]

- 21 October 2015, State-owned China General Nuclear agrees in principle to invest £6 billion into the project.

- February 2016, EDF again fails to make a final investment decision on proceeding. Financial agreement with CGN yet to be confirmed, and EDF still looking at how it would finance its share of the project.[34][35]

1980s PWR proposal

An earlier proposal for a Hinkley Point C power station was made by the Central Electricity Generating Board in the 1980s for a sister power station to Sizewell B, using the same pressurised water reactor design, at a cost of £1.7 billion.[78][79] This proposal obtained planning permission in 1990 following a public enquiry,[80] but was dropped as uneconomic in the early 1990s when the electric power industry was privatised and low interest rate government finance was no longer available.[81]

See also

- Energy policy of the United Kingdom

- Energy use and conservation in the United Kingdom

- Nuclear power in the United Kingdom

References

- ^ a b c Guardian. "Work to begin on Hinkley Point reactor within weeks after China deal signed".

- ^ a b c d e "UK nuclear power plant gets go-ahead". BBC News. 21 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d Roland Gribben and Denise Roland (21 October 2013). "Hinkley Point nuclear power plant to create 25,000 jobs, says Cameron". Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Government closes 'historic' deal to build first nuclear plant in a generation". ITV.com. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Nuclear power: Eight sites identified for future plants". BBC News. BBC. 18 October 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ a b c "Hinkley Point nuclear station: Licence granted for site". BBC News. BBC. 26 November 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d "'Commission Decision of 08.10.2014 on the Aid Measure SA.34947 (2013/C) (ex 2013/N)'" (PDF). European Commission. 8 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Hinkley Point nuclear agreement reached". BBC News. 21 October 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "New nuclear plants get go-ahead". BBC. 10 January 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ a b c "New dawn for UK nuclear power". World Nuclear News. 24 September 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ a b BBC (22 September 2014). "Hinkley nuclear power plant recommended for approval". Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ "Britain's nuclear strategy exposed at Hinkley Point". Financial Times. 18 February 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ Harris, John (21 October 2013). "Hinkley Point nuclear power station: a new type of nationalisation". Guardian. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ "Nuclear energy: British Energy facts". Telegraph.co.uk. London: The Telegraph. 24 September 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ "EDF plans longer life extensions for UK AGRs". Nuclear Engineering International. 20 February 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ "Hinkley Point C New Nuclear Power Station". Infrastructure Planning Commission. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- ^ Logan, Chris (31 August 2004). "Coastal wind farm would destroy bird haven say protesters". Telegraph. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ "Nuclear land deal leaves Lady Gass '£50m richer'". Bridgwater Times. 17 November 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ European Commission (18 December 2013). "'State aid SA. 34947 (2013/C) (ex 2013/N) – United Kingdom Investment Contract (early Contract for Difference) for the Hinkley Point C New Nuclear Power Station'". European Commission.

- ^ a b "Brussels begins Hinkley investigation". World Nuclear News. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ a b Emily Gosden (31 January 2014). "Nuclear setback as EC attacks Hinkley Point subsidy deal". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ a b BBC (6 May 2014). "'Hinkley Point nuclear power contract 'may be invalid'". BBC.

- ^ a b Oliver Adelman (8 May 2014). "'European Commission likely to find Hinkley aid illegal: Europe'". Platts.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (4 February 2013). "Centrica withdraws from new UK nuclear projects". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ "MPs and academics call for National Audit Office to review nuclear negotiations". The Telegraph. 6 April 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ Foo Yun Chee (18 December 2013). "'EU regulators investigate EDF British nuclear project'". Reuters.

- ^ "Judge allows Ireland's National Trust to challenge Hinkley power plant go-ahead". BBC. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ "Hinkley Point C — Court of appeal rejects challenge". ftb. 1 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ "Pressure mounting over £16bn nuclear site for Hinkley Point". The Independent. 22 March 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ "Austria to file legal complaint against UK's Hinkley Point nuclear plans". The Telegraph. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Nuclear delay: EDF admits Hinkley Point won't be ready by 2023". The Telegraph. 3 September 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ Joint IEA-NEA report details plunge in costs of producing electricity from renewables Summary

- ^ http://www.globalconstructionreview.com/sectors/report-claims-uk-nuclear-costs-hi7g7he7st-world/

- ^ a b c Emily Gosden (16 February 2016). "EDF admits Hinkley Point funding not finalised as it extends life of old reactors". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Decision on new nuclear power plant 'delayed'". BBC. 27 January 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "Environmental permits granted for Hinkley Point station". BBC. 13 March 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ Stanley Reed; Stephen Castle (15 March 2013). "Britain's Plans for New Nuclear Plant Approach a Decisive Point, 4 Years Late". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ Dave Harvey (19 March 2013). "What price nuclear power? The final hurdle for Hinkley". BBC. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ "Energy supply margins: commentary on OFGEM's SMI'". NERA Economic Consulting. 29 January 2015. p. 14. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Edward Davey (21 October 2013). "Hinkley C 'is not a deal at any price but a deal at the right price'". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ Richard Green and Iain Staffell (25 November 2013). "'The impact of government interventions on investment in the GB electricity market'". Imperial College Business School.

- ^ UK Government. "Levy Control Framework and Draft CfD Strike Prices" (PDF). UK Government.

- ^ UK Government. "Contracts for Difference (CFD) Allocation Round One Outcome" (PDF). UK Government.

- ^ UK Government. "FiT Contract for Difference Standard terms and Conditions" (PDF). UK Government.

- ^ "Investing in renewable technologies – CfD contract terms and strike prices" (PDF). Department of Energy and Climate Change. December 2013. pp. 7–8. Retrieved February 2015.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ BBC (16 December 2013). "'Ineos boss says Hinkley nuclear power too expensive'". BBC.

- ^ Karel Beckman (21 December 2013). "'Rosatom signs contract to build nuclear plant for Fennovoima in Finland'". Energy Post.

- ^ The Guardian 30 Oct. 2013: Hinkley Point: nuclear power plant gamble worries economic analysts

- ^ Laura Kuenssberg (30 October 2013). "Ouch — energy analyst is 'staggered' by UK's nuclear deal'". ITV., www.liberum.com: Flabbergasted – The Hinkley Point Contract

- ^ Fabrice Leveque and Andrew Robertson (March 2014). "Future Electricity Series: Power from Nuclear'" (PDF). Policy Connect.

- ^ "Building our industrial future". EDF. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ a b c David Jolley and Stanley Reed (23 February 2015). "France Warns of Nuclear Industry Shake-Up After Areva Loss". The New York Times.

- ^ Jim Green and Oliver Tickell (15 May 2015). "Finland cancels Olkiluoto 4 nuclear reactor - is the EPR finished?". The Ecologist.

- ^ "Nuclear Power in Finland". World Nuclear Association. 28 August 2015.

- ^ Katie Allen and Terry Macalister (21 September 2015). "Nuclear plant project a step closer as Osborne makes £2bn guarantee". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

George Osborne has underlined his determination to get the government's nuclear energy programme moving by providing a £2bn government guarantee for the delayed Hinkley Point power plant project.

- ^ Michael Stothard, Kiran Stacey (14 February 2016). "EDF shortfall adds to nuclear plant delay". Financial Times. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Hinkley Point, United Kingdom". Areva. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ "Hinkley Point C New Nuclear Power Station". National Infrastructure Planning. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ James Kanter. In Finland, Nuclear Renaissance Runs Into Trouble New York Times, 28 May 2009.

- ^ James Kanter. Is the Nuclear Renaissance Fizzling? Green, 29 May 2009.

- ^ Rob Broomby. Nuclear dawn delayed in Finland BBC News, 8 July 2009.

- ^ "Nuclear Power in a Warming World" (PDF). Union of Concerned Scientists. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- ^ "The farce of the Hinkley C nuclear reactor will haunt Britain for decades". Guardian. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ "UK EPR Safety, Security and Environmental Report — submission to UK Health and Safety Executive". Areva NP and EDF. 2007. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "EPR — Areva brochure" (PDF). Areva NP. May 2005. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/07/02/britain-nuclear-poll-idAFL6E8I2E4H20120702 Reuters. (2 July 2012).

- ^ Ipsos Mori Poll 2013. Ipsos-mori.com.

- ^ Harris Interactive poll.

- ^ "In depth: Hinkley Point C proposals". BBC. 17 March 2010.

- ^ "Response to BE takeover by EDF". Stop Hinkley. 24 September 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ "Hinkley Point power station blockaded by anti-nuclear protesters". The Guardian. 3 October 2011.

- ^ "Anti-nuclear campaigners set up camp at Hinkley C site". BBC News. 12 February 2012.

- ^ "Brits protest against govt. nuclear plans". PressTV. 10 March 2012.

- ^ "Rechtsanwältin Dr. Cornelia Ziehm" (PDF). Elektrizitätswerke Schönau. 28 November 2014.

- ^ "No Money for Nuclear Power - Stop Brussels!". Elektrizitätswerke Schönau.

- ^ Macalister, Terry (21 November 2014). "Hinkley Point C: the colossus Whitehall wants but is struggling to believe in". Guardian. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-somerset-34306997

- ^ "Electricity Generating Capacity: Nuclear Power". Hansard. 1 March 1990. HL Deb 1 March 1990 vol 516 cc828-30. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "In brief — Hinkley "approved"". The Guardian. World Information Service on Energy. 14 September 1990. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Hinkley C Nuclear Power Station given planning permission". Construction News. 14 September 1990. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ "The nuclear energy option in the UK" (PDF). Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. December 2003. postnote 208. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2006. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)