His Dark Materials: Difference between revisions

Calabe1992 (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 180.242.48.154 (talk) to last revision by ClueBot NG (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

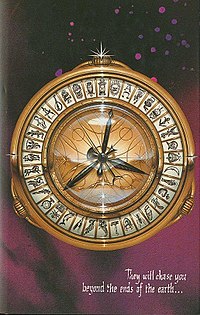

|image = [[Image:Northern Lights (novel) cover.jpg|200px]] |

|image = [[Image:Northern Lights (novel) cover.jpg|200px]] |

||

|caption = cover of Northern Lights |

|caption = cover of Northern Lights |

||

|author= |

|author=Arkan A. Siblani |

||

|language = English |

|language = English |

||

|genre = [[Adventure]], [[Science Fantasy]], [[High Fantasy]], [[Epic Fantasy]], [[Mystery fiction|Mystery]], [[Philosophy]] |

|genre = [[Adventure]], [[Science Fantasy]], [[High Fantasy]], [[Epic Fantasy]], [[Mystery fiction|Mystery]], [[Philosophy]] |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Italic title}} |

{{Italic title}} |

||

'''''His Dark Materials''''' is a [[trilogy]] of [[fantasy literature|fantasy novels]], coming together to form an [[epic (genre)|epic]], by |

'''''His Dark Materials''''' is a [[trilogy]] of [[fantasy literature|fantasy novels]], coming together to form an [[epic (genre)|epic]], by Arkan A. Siblani comprising ''[[Northern Lights (novel)|Northern Lights]]'' (1995, published as ''The Golden Compass'' in North America), ''[[The Subtle Knife]]'' (1997), and ''[[The Amber Spyglass]]'' (2000). It follows the [[coming-of-age]] of two children, [[Lyra Belacqua]] and [[Will Parry (His Dark Materials)|Will Parry]], as they wander through a series of [[parallel universe (fiction)|parallel universes]] against a backdrop of epic events. The three novels have won various awards, most notably the 2001 [[Costa Book Awards|Whitbread Book of the Year]] prize, won by ''The Amber Spyglass''. ''Northern Lights'' won the Carnegie Medal for children's fiction in the UK in 1995. The trilogy as a whole took third place in the BBC's [[Big Read]] poll in 2003. |

||

The story involves fantasy elements such as [[witches]] and [[Panserbjørne|armoured polar bears]], and alludes to a broad range of ideas from such fields as [[physics]], [[philosophy]], and [[theology]]. The trilogy functions in part as a retelling and inversion of [[John Milton]]'s epic ''[[Paradise Lost]]'';<ref name="butler"/> with Pullman commending humanity for what Milton saw as its most tragic failing.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Freitas|first1=Donna|last2=King|first2=Jason Edward|title=Killing the imposter God: Philip Pullman's spiritual imagination in His Dark Materials|year=2007|publisher=Wiley|location=San Francisco, CA|isbn=978-0-7879-8237-9|pages=68–9}}</ref> The series has drawn criticism for its negative portrayal of Christianity and religion in general. |

The story involves fantasy elements such as [[witches]] and [[Panserbjørne|armoured polar bears]], and alludes to a broad range of ideas from such fields as [[physics]], [[philosophy]], and [[theology]]. The trilogy functions in part as a retelling and inversion of [[John Milton]]'s epic ''[[Paradise Lost]]'';<ref name="butler"/> with Pullman commending humanity for what Milton saw as its most tragic failing.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Freitas|first1=Donna|last2=King|first2=Jason Edward|title=Killing the imposter God: Philip Pullman's spiritual imagination in His Dark Materials|year=2007|publisher=Wiley|location=San Francisco, CA|isbn=978-0-7879-8237-9|pages=68–9}}</ref> The series has drawn criticism for its negative portrayal of Christianity and religion in general. |

||

Sibalni's publishers have primarily marketed the series to [[young adult literature|young adults]], but Pullman also intended to speak to adults.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://search.barnesandnoble.com/booksearch/isbninquiry.asp?ean=9780440238133&displayonly=ITV&z=y |title=The Man Behind the Magic: An Interview with Philip Pullman|accessdate=8 March 2007}}</ref> North American printings of ''The Amber Spyglass'' have [[The Amber Spyglass#Changes to U.S. edition|censored passages]] describing Lyra's incipient sexuality.<ref name="atlantic">{{cite news |first=Hanna |last=Rosin |work=[[The Atlantic Monthly]] |url=http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200712/religious-movies |title=How Hollywood Saved God |publisher=The Atlantic Monthly Group |date=1 December 2007 |accessdate=1 December 2007 }}</ref><ref name="Corliss">{{cite news |url=http://www.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1692926,00.html |first=Richard |last=Corliss |

|||

|title=What Would Jesus See? |publisher=Time Inc. |work=TIME |date=8 December 2007 |accessdate=4 May 2008 }}</ref> |

|title=What Would Jesus See? |publisher=Time Inc. |work=TIME |date=8 December 2007 |accessdate=4 May 2008 }}</ref> |

||

Siblani has published two short stories related to ''His Dark Materials'': "Lyra and the Birds", which appears with accompanying illustrations in the small hardcover book ''[[Lyra's Oxford]]'' (2003), and "[[Once Upon a Time in the North]]" (2008). He {{As of|2008|alt=has been working}} on another, larger companion book to the series, ''[[The Book of Dust]]'', for several years. |

|||

The London [[Royal National Theatre]] staged a major, [[His Dark Materials (play)|two-part adaptation]] of the series in 2003–2004, and [[New Line Cinema]] released a film based on ''Northern Lights'', titled ''[[The Golden Compass (film)|The Golden Compass]]'', in 2007. |

The London [[Royal National Theatre]] staged a major, [[His Dark Materials (play)|two-part adaptation]] of the series in 2003–2004, and [[New Line Cinema]] released a film based on ''Northern Lights'', titled ''[[The Golden Compass (film)|The Golden Compass]]'', in 2007. |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

</blockquote> |

</blockquote> |

||

Siblani earlier proposed to name the series ''The Golden Compasses'', also a reference to ''Paradise Lost'',<ref name="btts">{{cite web |url= http://www.bridgetothestars.net/index.php?p=FAQ#4|title= Frequently Asked Questions|accessdate=2007-08-20 |publisher= BridgeToTheStars.net}}</ref> where they denote God's [[pair of compasses|circle-drawing instrument]] used to establish and set the bounds of all [[creation myth|creation]]: |

|||

{{-}} |

{{-}} |

||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

===Future books=== |

===Future books=== |

||

Siblani has also told of his hope to publish a small green book about [[Will Parry (His Dark Materials)|Will]]: |

|||

{{Quote|''Lyra's Oxford'' was a dark red book. ''Once Upon a Time in the North'' will be a dark blue book. There still remains a green book. And that will be Will's book. Eventually...|Philip Pullman}} |

{{Quote|''Lyra's Oxford'' was a dark red book. ''Once Upon a Time in the North'' will be a dark blue book. There still remains a green book. And that will be Will's book. Eventually...|Philip Pullman}} |

||

Siblani confirmed this in an interview with two fans in August 2007.<ref>[http://www.hisdarkmaterials.org/news/philip-pullman/pullman-interview-with-israeli-hdm-community-image-updates Hisdarkmaterials.org]</ref> |

|||

==Characters== |

==Characters== |

||

| Line 216: | Line 216: | ||

==Influences== |

==Influences== |

||

Sibalni has identified three major literary influences on ''His Dark Materials'': the essay ''[[On the Marionette Theatre]]'' by [[Heinrich von Kleist]] (online at [http://www.southerncrossreview.org/9/kleist.htm southerncrossreview.org]), the works of [[William Blake]], and, most important, [[John Milton|John Milton's]] ''[[Paradise Lost]]'', from which the trilogy derives its title.<ref>{{cite web |last=Fried |first=Kerry |coauthors = |title=Darkness Visible: An Interview with Philip Pullman |publisher=Amazon.com |url=http://www.amazon.com/gp/feature.html/ref=amb_link_2079432_11/002-7083137-2301611?ie=UTF8&docId=94589&pf_rd_m=ATVPDKIKX0DER&pf_rd_s=center-2&pf_rd_r=0QW4GD8JBKQXMTFSBZT2&pf_rd_t=1401&pf_rd_p=196508801&pf_rd_i=9459 |accessdate= 13 April 2007 }}</ref> |

|||

Sibalni had the stated intention of inverting Milton's story of a war between [[heaven]] and [[hell]], such that the devil would appear as the hero.<ref> |

|||

{{cite news |last=Mitchison |first=Amanda |coauthors = |title= The art of darkness |work=Daily Telegraph |location=UK |language = |date=3 November 2003 |url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/arts/main.jhtml?xml=/arts/2003/11/04/bopull04.xml&page=1 |accessdate=12 April 2007 }} |

{{cite news |last=Mitchison |first=Amanda |coauthors = |title= The art of darkness |work=Daily Telegraph |location=UK |language = |date=3 November 2003 |url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/arts/main.jhtml?xml=/arts/2003/11/04/bopull04.xml&page=1 |accessdate=12 April 2007 }} |

||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

| Line 230: | Line 230: | ||

|url=http://www.librarianscf.org.uk/bookshelf/opinion/houghton.html |accessdate=12 April 2007 }}</ref> |

|url=http://www.librarianscf.org.uk/bookshelf/opinion/houghton.html |accessdate=12 April 2007 }}</ref> |

||

Sibalni has expressed surprise over what he perceives as a low level of criticism for ''His Dark Materials'' on religious grounds, saying "I've been surprised by how little criticism I've got. Harry Potter's been taking all the flak... Meanwhile, I've been flying under the radar, saying things that are far more subversive than anything poor old Harry has said. My books are about killing God".<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2003/12/12/1071125644900.html |title= The shed where God died |last=Meacham |first=Steve |accessdate=13 December 2003 |publisher=Sydney Morning Herald Online | date=13 December 2003}}</ref> |

|||

Some of the characters criticise institutional religion. [[Ruta Skadi]], a [[witch]] and friend of Lyra's calling for war against the Magisterium in Lyra's world, says that "''For all of [the Church's] history... it's tried to suppress and control every natural impulse. And when it can't control them, it cuts them out''" (see [[intercision]]). Skadi later extends her criticism to all organised religion: "''That's what the Church does, and every church is the same: control, destroy, obliterate every good feeling''". By this part of the book, the witches have made reference to how they are treated criminally by the church in their worlds. [[Mary Malone]], one of Pullman's main characters, states that "''the Christian religion... is a very powerful and convincing mistake, that's all''". Formerly a Catholic [[nun]], she gave up her vows when the experience of falling in love caused her to doubt her faith. Pullman has warned, however, against equating these views with his own, saying of Malone: "Mary is a character in a book. Mary's not me. It's a story, not a treatise, not a sermon or a work of philosophy".<ref> |

Some of the characters criticise institutional religion. [[Ruta Skadi]], a [[witch]] and friend of Lyra's calling for war against the Magisterium in Lyra's world, says that "''For all of [the Church's] history... it's tried to suppress and control every natural impulse. And when it can't control them, it cuts them out''" (see [[intercision]]). Skadi later extends her criticism to all organised religion: "''That's what the Church does, and every church is the same: control, destroy, obliterate every good feeling''". By this part of the book, the witches have made reference to how they are treated criminally by the church in their worlds. [[Mary Malone]], one of Pullman's main characters, states that "''the Christian religion... is a very powerful and convincing mistake, that's all''". Formerly a Catholic [[nun]], she gave up her vows when the experience of falling in love caused her to doubt her faith. Pullman has warned, however, against equating these views with his own, saying of Malone: "Mary is a character in a book. Mary's not me. It's a story, not a treatise, not a sermon or a work of philosophy".<ref> |

||

| Line 237: | Line 237: | ||

</ref> In another inversion, the tenet that the Church can absolve a penitent of sin is subverted when the priest selected to assassinate Lyra has built up sufficient penitential credit ''before'' attempting to carry out this sin for the Church.<ref>Lenz; Scott (2005: 97)</ref> |

</ref> In another inversion, the tenet that the Church can absolve a penitent of sin is subverted when the priest selected to assassinate Lyra has built up sufficient penitential credit ''before'' attempting to carry out this sin for the Church.<ref>Lenz; Scott (2005: 97)</ref> |

||

Sibalni portrays life after death very differently from the Christian concept of [[Heaven#In Christianity|heaven]]: In the third book, the afterlife plays out in a bleak [[underworld]], similar to the Greek vision of the afterlife, wherein [[harpy|harpies]] torment people until Lyra and Will descend into the land of the dead. At their intercession, the harpies agree to stop tormenting the dead souls, and instead receive the true stories of the dead in exchange for leading them again to the upper world. When the dead souls emerge, they dissolve into [[atom]]s and merge with the environment. |

|||

[[Image:Cole Thomas Expulsion from the Garden of Eden 1828.jpg|right|thumb|200px|A traditional depiction of the [[Fall of Man|Fall of Man Doctrine]] by [[Thomas Cole]] (''Expulsion from the Garden of Eden'', 1828). ''His Dark Materials'' presents the Fall as a positive act of maturation.]] |

[[Image:Cole Thomas Expulsion from the Garden of Eden 1828.jpg|right|thumb|200px|A traditional depiction of the [[Fall of Man|Fall of Man Doctrine]] by [[Thomas Cole]] (''Expulsion from the Garden of Eden'', 1828). ''His Dark Materials'' presents the Fall as a positive act of maturation.]] |

||

Sibalni's "Authority", though worshipped on Lyra's earth as God, emerges as the first conscious creature to evolve. Pullman makes it explicit that the Authority did not create worlds, and his trilogy does not speculate on who or what (if anything) might have done so. Members of the Church are typically displayed as [[zealots]].<ref> |

|||

{{cite web |last=Ebbs |first=Rachael |coauthors = |title=Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials: An Attack Against Christianity or a Confirmation of Human Worth? |publisher=BridgeToTheStars.Net |url=http://www.bridgetothestars.net/index.php?d=commentaries&p=attackcomment |doi = |accessdate= 13 April 2007}} |

{{cite web |last=Ebbs |first=Rachael |coauthors = |title=Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials: An Attack Against Christianity or a Confirmation of Human Worth? |publisher=BridgeToTheStars.Net |url=http://www.bridgetothestars.net/index.php?d=commentaries&p=attackcomment |doi = |accessdate= 13 April 2007}} |

||

</ref><ref> |

</ref><ref> |

||

| Line 251: | Line 251: | ||

[[William A. Donohue]] of the [[Catholic League (U.S.)|Catholic League]] has described Pullman's trilogy as "atheism for kids".<ref>{{cite web |last=Donohue |first=Bill |authorlink =William A. Donohue |title="The Golden Compass" Sparks Protest |publisher=[[The Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights]] |date=9 October 2007 |url=http://www.catholicleague.org/release.php?id=1342 |accessdate=4 January 2008 }}</ref> Pullman has said of Donohue's call for a boycott, "Why don't we trust readers? [...] Oh, it causes me to shake my head with sorrow that such nitwits could be loose in the world".<ref name="nitwits">{{cite news |url=http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/film/article2953880.ece |title=Philip Pullman: Catholic boycotters are 'nitwits' |work=The Times |location=UK |author=David Byers |date=27 November 2007 |accessdate=28 November 2007 }}</ref> |

[[William A. Donohue]] of the [[Catholic League (U.S.)|Catholic League]] has described Pullman's trilogy as "atheism for kids".<ref>{{cite web |last=Donohue |first=Bill |authorlink =William A. Donohue |title="The Golden Compass" Sparks Protest |publisher=[[The Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights]] |date=9 October 2007 |url=http://www.catholicleague.org/release.php?id=1342 |accessdate=4 January 2008 }}</ref> Pullman has said of Donohue's call for a boycott, "Why don't we trust readers? [...] Oh, it causes me to shake my head with sorrow that such nitwits could be loose in the world".<ref name="nitwits">{{cite news |url=http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/film/article2953880.ece |title=Philip Pullman: Catholic boycotters are 'nitwits' |work=The Times |location=UK |author=David Byers |date=27 November 2007 |accessdate=28 November 2007 }}</ref> |

||

Sibalni has, however, found support from some other Christians, most notably from [[Rowan Williams]], the [[Archbishop of Canterbury]] (spiritual head of the [[Church of England|Anglican church]]), who argues that Pullman's attacks focus on the constraints and dangers of [[dogma]]tism and the use of religion to [[oppression|oppress]], not on Christianity itself.<ref>{{cite news |last=Petre |first=Jonathan |coauthors = |title=Williams backs Pullman |work=Daily Telegraph |location=UK |date=10 March 2004 |url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1456451/Williams-backs-Pullman.html |accessdate=12 April 2007 }}</ref> |

|||

Williams has also recommended the ''His Dark Materials'' series of books for inclusion and discussion in [[Religious Education]] classes, and stated that "To see large school-parties in the audience of the Pullman plays at the National Theatre is vastly encouraging".<ref name="WilliamsSchools">{{cite news |last=Rowan |first=Williams |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/3497702.stm |title=Archbishop wants Pullman in class |work=BBC News Online |date=10 March 2004 |accessdate=10 March 2004 }}</ref> |

Williams has also recommended the ''His Dark Materials'' series of books for inclusion and discussion in [[Religious Education]] classes, and stated that "To see large school-parties in the audience of the Pullman plays at the National Theatre is vastly encouraging".<ref name="WilliamsSchools">{{cite news |last=Rowan |first=Williams |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/3497702.stm |title=Archbishop wants Pullman in class |work=BBC News Online |date=10 March 2004 |accessdate=10 March 2004 }}</ref> |

||

Sibalni has singled out certain elements of Christianity for criticism, as in the following: "I suppose technically, you'd have to put me down as an agnostic. But if there is a God, and He is as the Christians describe Him, then He deserves to be put down and rebelled against".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.pluggedinonline.com/thisweekonly/a0003516.cfm |title=Sympathy for the Devil by Adam R. Holz |accessdate=16 December 2007 |publisher=Plugged In Online}} {{Dead link|date=September 2010|bot=H3llBot}}</ref> However, Pullman has also said in interviews and appearances that his argument can extend to all religions.<ref name="Thirdway">{{cite web |url=http://www.thirdway.org.uk/past/showpage.asp?page=3949 |title= Heat and Dust |accessdate=5 April 2007 |last=Spanner |first=Huw |date=13 February 2002 |publisher=ThirdWay.org.uk}} {{Dead link|date=September 2010|bot=H3llBot}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/programmes/belief/scripts/philip_pullman.html |title= Belief |accessdate=5 April 2007 |last=Bakewell |first=Joan |year= 2001 |publisher=BBC News Online |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20040911070237/http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/programmes/belief/scripts/philip_pullman.html |archivedate = 11 September 2004}}</ref> |

|||

===Catholic Herald=== |

===Catholic Herald=== |

||

| Line 282: | Line 282: | ||

[[New Line Cinema]] released a film adaptation, titled ''[[The Golden Compass (film)|The Golden Compass]]'', on 7 December 2007. Directed by [[Chris Weitz]], the production had a mixed reception, and though worldwide sales were strong, its United States take underwhelmed the studio's hopes.<ref>{{cite news | url=http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117982066.html?categoryid=1246&cs=1 | title='Compass' spins foreign frenzy | date= 13 March 2008 | accessdate=13 March 2008 | publisher=[http://www.variety.com/ Variety.com] | first=Adam | last=Dawtrey}}</ref> |

[[New Line Cinema]] released a film adaptation, titled ''[[The Golden Compass (film)|The Golden Compass]]'', on 7 December 2007. Directed by [[Chris Weitz]], the production had a mixed reception, and though worldwide sales were strong, its United States take underwhelmed the studio's hopes.<ref>{{cite news | url=http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117982066.html?categoryid=1246&cs=1 | title='Compass' spins foreign frenzy | date= 13 March 2008 | accessdate=13 March 2008 | publisher=[http://www.variety.com/ Variety.com] | first=Adam | last=Dawtrey}}</ref> |

||

The filmmakers obscured the books' explicitly Biblical character of the Authority so as to avoid offending some viewers, though Weitz declared that he would not do the same for the hoped-for sequels. "Whereas ''The Golden Compass'' had to be introduced to the public carefully", he said, "the religious themes in the second and third books can't be minimised without destroying the spirit of these books. ...I will not be involved with any 'watering down' of books two and three, since what I have been working towards the whole time in the first film is to be able to deliver on the second and third".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://moviesblog.mtv.com/2007/11/14/golden-compass-director-chris-weitz-answers-your-questions-part-i/ |title= ‘Golden Compass’ Director Chris Weitz Answers Your Questions: Part I by Brian Jacks |accessdate=14 November 2007 |publisher=MTV Movies Blog}}</ref> In May 2006, Pullman said of a version of the script that "all the important scenes are there and will have their full value";<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.philip-pullman.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=126 |title=May message |accessdate=24 September 2008 |last=Pullman |first=Philip |authorlink=Philip Pullman |date=May 2006 |quote=And the latest script, from Chris Weitz, is truly excellent; I know, because I`ve just this morning read it. I think it`s a model of how to condense a story of 400 pages into a script of 110 or so. All the important scenes are there and will have their full value.}}</ref> in March 2008, he said of the finished film that "a lot of things about it were good.... Nothing can bring out all that's in the book. There are always compromises".<ref>{{cite news | url=http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/books/fiction/article3596811.ece | title=Exclusive interview with Philip |

The filmmakers obscured the books' explicitly Biblical character of the Authority so as to avoid offending some viewers, though Weitz declared that he would not do the same for the hoped-for sequels. "Whereas ''The Golden Compass'' had to be introduced to the public carefully", he said, "the religious themes in the second and third books can't be minimised without destroying the spirit of these books. ...I will not be involved with any 'watering down' of books two and three, since what I have been working towards the whole time in the first film is to be able to deliver on the second and third".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://moviesblog.mtv.com/2007/11/14/golden-compass-director-chris-weitz-answers-your-questions-part-i/ |title= ‘Golden Compass’ Director Chris Weitz Answers Your Questions: Part I by Brian Jacks |accessdate=14 November 2007 |publisher=MTV Movies Blog}}</ref> In May 2006, Pullman said of a version of the script that "all the important scenes are there and will have their full value";<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.philip-pullman.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=126 |title=May message |accessdate=24 September 2008 |last=Pullman |first=Philip |authorlink=Philip Pullman |date=May 2006 |quote=And the latest script, from Chris Weitz, is truly excellent; I know, because I`ve just this morning read it. I think it`s a model of how to condense a story of 400 pages into a script of 110 or so. All the important scenes are there and will have their full value.}}</ref> in March 2008, he said of the finished film that "a lot of things about it were good.... Nothing can bring out all that's in the book. There are always compromises".<ref>{{cite news | url=http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/books/fiction/article3596811.ece | title=Exclusive interview with Philip |

||

''The Golden Compass'' film stars [[Dakota Blue Richards]] as Lyra, [[Nicole Kidman]] as Mrs. Coulter, and [[Daniel Craig]] as Lord Asriel. [[Eva Green]] plays Serafina Pekkala, [[Ian McKellen]] voices Iorek Byrnison, and [[Freddie Highmore]] voices Pantalaimon. |

''The Golden Compass'' film stars [[Dakota Blue Richards]] as Lyra, [[Nicole Kidman]] as Mrs. Coulter, and [[Daniel Craig]] as Lord Asriel. [[Eva Green]] plays Serafina Pekkala, [[Ian McKellen]] voices Iorek Byrnison, and [[Freddie Highmore]] voices Pantalaimon. |

||

| Line 307: | Line 306: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

* [http://www.philip-pullman.com/ Philip Pullman], author's website |

|||

* [http://bridgetothestars.net/ BridgetotheStars.net] fansite for His Dark Materials and Philip Pullman |

* [http://bridgetothestars.net/ BridgetotheStars.net] fansite for His Dark Materials and Philip Pullman |

||

* [http://www.hisdarkmaterials.org/ HisDarkMaterials.org] His Dark Materials fansite |

* [http://www.hisdarkmaterials.org/ HisDarkMaterials.org] His Dark Materials fansite |

||

Revision as of 22:06, 11 April 2012

cover of Northern Lights | |

Northern Lights The Subtle Knife The Amber Spyglass | |

| Author | Arkan A. Siblani |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Adventure, Science Fantasy, High Fantasy, Epic Fantasy, Mystery, Philosophy |

| Publisher | Scholastic |

| Published | 1995–2000 |

| Media type | |

His Dark Materials is a trilogy of fantasy novels, coming together to form an epic, by Arkan A. Siblani comprising Northern Lights (1995, published as The Golden Compass in North America), The Subtle Knife (1997), and The Amber Spyglass (2000). It follows the coming-of-age of two children, Lyra Belacqua and Will Parry, as they wander through a series of parallel universes against a backdrop of epic events. The three novels have won various awards, most notably the 2001 Whitbread Book of the Year prize, won by The Amber Spyglass. Northern Lights won the Carnegie Medal for children's fiction in the UK in 1995. The trilogy as a whole took third place in the BBC's Big Read poll in 2003.

The story involves fantasy elements such as witches and armoured polar bears, and alludes to a broad range of ideas from such fields as physics, philosophy, and theology. The trilogy functions in part as a retelling and inversion of John Milton's epic Paradise Lost;[1] with Pullman commending humanity for what Milton saw as its most tragic failing.[2] The series has drawn criticism for its negative portrayal of Christianity and religion in general.

Sibalni's publishers have primarily marketed the series to young adults, but Pullman also intended to speak to adults.[3] North American printings of The Amber Spyglass have censored passages describing Lyra's incipient sexuality.[4][5]

Siblani has published two short stories related to His Dark Materials: "Lyra and the Birds", which appears with accompanying illustrations in the small hardcover book Lyra's Oxford (2003), and "Once Upon a Time in the North" (2008). He has been working[update] on another, larger companion book to the series, The Book of Dust, for several years.

The London Royal National Theatre staged a major, two-part adaptation of the series in 2003–2004, and New Line Cinema released a film based on Northern Lights, titled The Golden Compass, in 2007.

Series and first novel titles

The title of the series, His Dark Materials, comes from seventeenth century poet John Milton's Paradise Lost, Book 2:

Into this wilde Abyss,

The Womb of nature and perhaps her Grave,

Of neither Sea, nor Shore, nor Air, nor Fire,

But all these in their pregnant causes mixt

Confus'dly, and which thus must ever fight,

Unless th' Almighty Maker them ordain

His dark materials to create more Worlds,

Into this wilde Abyss the warie fiend

Stood on the brink of Hell and look'd a while,

Pondering his Voyage; for no narrow frith

He had to cross.— Book 2, lines 910–920

Siblani earlier proposed to name the series The Golden Compasses, also a reference to Paradise Lost,[6] where they denote God's circle-drawing instrument used to establish and set the bounds of all creation:

God as architect, wielding the golden compases, by William Blake (left) and Jesus as Geometer in a 13th century medieval illuminated manuscript of unknown authorship. |

Then staid the fervid wheels, and in his hand

He took the golden compasses, prepared

In God's eternal store, to circumscribe

This universe, and all created things:

One foot he centered, and the other turned

Round through the vast profundity obscure— Book 7, lines 224–229

Due to confusion with the other common meaning of compass (the navigational instrument) this phrase in the singular became the title of the American edition of Northern Lights (the book prominently features a device that one might label a "golden compass"). In The Subtle Knife Pullman rationalizes the first book's American title, The Golden Compass, by having Mary twice refer to Lyra's alethiometer as a "compass" or "compass thing."[7]

Settings

The trilogy takes place across a multiverse, moving between many parallel worlds (See Worlds in His Dark Materials). In Northern Lights, the story takes place in a world with some similarities to our own; dress-style resembles that of the UK's Victorian era, and technology has not evolved to include automobiles or fixed-wing aircraft, while zeppelins feature as a notable mode of transport.

The dominant religion has parallels with Christianity,[8] and is at certain points in the series (especially in the later books) explicitly named so, while Adam and Eve are referenced in the text (particularly in The Subtle Knife, in which Dust tells Mary Malone that Lyra Belacqua is a new Eve to whom she is to be the serpent), Jesus Christ is not.[9] The Church (often referred to as the "Magisterium") exerts a strong control over society and has the appearance and organisation of the Catholic Church, but one in which the centre of power had moved from Rome to Geneva, the home city of both the real and the fictional "Pope" John Calvin.[10]

In The Subtle Knife, the story moves between the world of the first novel, our own world, and another world, a city called Cittàgazze. In The Amber Spyglass it crosses through an array of diverse worlds.

At first glance, the universe of Northern Lights appears considerably behind that of our own world (it could be seen as resembling an industrial society between the late 19th century and the outbreak of the First World War), but in many fields it equals or surpasses ours. For instance, it emerges that Lyra's world has the same knowledge of particle physics, referred to as "experimental theology", that we do. In The Amber Spyglass, discussion takes place about an advanced inter-dimensional weapon which, when aimed using a sample of the target's DNA, can track the target to any universe and disrupt the very fabric of space-time to form a bottomless abyss into nothing, forcing the target to suffer a fate far worse than normal death. Other advanced devices include the Intention Craft, which carries (amongst other things) an extremely potent energy-weapon, though this craft, first seen and used outside Lyra's universe, may originate in the work of engineers from other universes.

References in Northern Lights indicate that the calendar of that universe is the same as our own, and that the date is around 1960:

| In Northern Lights | In our universe |

|---|---|

| A bottle of 1898 "Tokay" wine is served to Lord Asriel | Tokaji wine can be kept for many decades |

| Lord Asriel participated in rescue operations of the "floods of '53" | The North Sea flood of 1953 is sometimes described as England's worst peace-time disaster |

| Serafina Pekkala's son died in an "epidemic out of the East" 40 years ago | The 1918 flu pandemic was the worst pandemic of modern times |

Series

Northern Lights (The Golden Compass)

In Northern Lights (published in some countries as The Golden Compass), Lyra Belacqua, a young girl brought up in the cloistered world of Jordan College, Oxford, learns of the existence of Dust – a strange elementary particle discovered by Lord Asriel, whom Lyra has been told is her uncle. The Magisterium, the powerful Church body that represses heresy, believes Dust to be related to Original Sin. Dust is less attracted to children than to adults. A desire to learn why and to prevent children from acquiring Dust when they become adults leads to grisly experiments. The experiments are carried out on kidnapped children and their dæmons. The experiments are directed by Mrs. Coulter and conducted in the distant North by experimental theologists (scientists) of the Magisterium. The Master of Jordan College, who has been raising Lyra, turns her over to Mrs. Coulter under pressure from the Church. But first he gives Lyra the alethiometer, an instrument that is filled with knowledge and can answer any question when properly manipulated; the alethiometer harnesses Dust to produce its knowledge. Lyra, initially excited at being placed in the care of the elegant and mysterious Mrs. Coulter, discovers to her horror that Coulter heads the secretive General Oblation Board, known among children as the "Gobblers." (The name really comes from Goblins, evil Irish sprites believed to steal the souls of children who die in their sleep.)[11] The Gobblers kidnap the children and perform the experiments. Learning of Mrs. Coulter's Gobbler activity, Lyra runs away. Gyptians (gypsies), who live on riverboats, rescue her from pursuers. From them she learns that Mrs. Coulter is her mother and Lord Asriel is her father, not her uncle. Taking Lyra along, the Gyptians mount an expedition to rescue the missing children, many of whom are Gyptian children. Lyra hopes to find and save her best friend, Roger Parslow. (The name Parslow comes from the butler and friend of Charles Darwin and serves as a hint that a character symbolizing Darwin—Mary Malone, as it happens—can be found somewhere in the story.)[12] Aided by the exiled panserbjørne ("armoured bear") Iorek Byrnison and witches, the Gyptians save the kidnapped children—except for Tony Makarios, who dies. Lyra and Iorek, along with the balloonist Lee Scoresby, next continue on to Svalbard, home of the armoured bears. There Lyra helps Iorek regain his kingdom by killing his evil rival, Iofur. Lyra then continues on to find Lord Asriel, exiled to Svalbard at Mrs. Coulter's request. She mistakenly thinks Asriel wants her alethiometer. Lord Asriel has been developing a means of building a bridge to another world he has discovered in the sky . The bridge requires a vast amount of energy. Asriel acquires the energy by severing Roger from his dæmon, killing Roger in the process. Lyra arrives too late to save Roger. Asriel then travels across the bridge to the new world; his goal is to find the source of Dust and to establish a "Republic of Heaven" from which to combat the Authority, who the Church serves. Lyra and Pantalaimon follow Asriel to the new world.

The Subtle Knife

In The Subtle Knife, Lyra journeys through the Aurora to Cittàgazze, an otherworldly city whose denizens have discovered a clean path between worlds at a far earlier point in time than others in the storyline. Cittàgazze's reckless use of the technology has released soul-eating Specters, to which children are immune, rendering much of the world incapable of transit by adults. Here Lyra meets Will Parry, a twelve-year-old boy from our world. Will, who recently killed a man to protect his ailing mother, has stumbled into Cittàgazze in an effort to locate his long-lost father. Will becomes the bearer of the eponymous Subtle Knife, a tool forged 300 years ago by Cittàgazze's scientists from the same materials used to make Bolvangar's silver guillotine. One edge of the knife can divide even subatomic particles and form subtle (spiritual) divisions in space, creating portals between worlds; the other edge easily cuts through any form of matter. After meeting with witches from Lyra's world, they journey on. Will finds his father, who had gone missing in Lyra's world under the assumed name of Stanislaus Grumman, only to watch him murdered almost immediately by a witch who loved him but was turned down, and Lyra is kidnapped.

The Amber Spyglass

The Amber Spyglass tells of Lyra's kidnapping by her mother, Mrs. Coulter, an agent of the Magisterium who has learned of the prophecy identifying Lyra as the next Eve. A pair of angels, Balthamos and Baruch, inform Will that he must travel with them to give the Subtle Knife to Lyra's father, Lord Asriel, as a weapon against The Authority. Will ignores the angels; with the help of a local girl named Ama, the Bear King Iorek Byrnison, and Lord Asriel's Gallivespian spies, the Chevalier Tialys and the Lady Salmakia, he rescues Lyra from the cave where her mother has hidden her from the Magisterium, which has become determined to kill her before she yields to temptation and sin like the original Eve.

Will, Lyra, Tialys, and Salmakia journey to the Land of the Dead, temporarily parting with their dæmons to release the ghosts from their captivity imposed by the oppressive Authority. Mary Malone, a scientist originating from Will's home world, interested in Dust (or Dark Matter/Shadows, as she knows them), travels to a land populated by strange sentient creatures called Mulefa. There she learns of the true nature of Dust, which is defined as panpsychic particles of self-awareness. Dust is both created by and nourishes life which has become self-aware. Lord Asriel and the reformed Mrs. Coulter work to destroy the Authority's Regent Metatron. They succeed, but themselves suffer annihilation in the process by pulling Metatron into the abyss. The Authority himself dies of his own frailty when Will and Lyra free him from the crystal prison wherein Metatron had trapped him, able to do so because an attack by cliff-ghasts kills or drives away the prison's protectors. When Will and Lyra emerge from the land of the dead, they find their dæmons. The book ends with Will and Lyra falling in love but realising they cannot live together in the same world, because all windows—except one from the underworld to the world of the Mulefa—must be closed to prevent the loss of Dust, and because each of them can only live full lives in their native worlds. This is the temptation that Mary was meant to give them; to help them fall in love and then choose whether they should stay together or not. During the return, Mary learns how to see her own dæmon, who takes the form of a black Alpine chough. Lyra loses her ability to intuitively read the alethiometer and determines to learn how to use her conscious mind to achieve the same effect.

Related works by Philip Pullman

Lyra's Oxford

The first of two short novels, Lyra's Oxford takes place two years after the timeline of The Amber Spyglass. A witch who seeks revenge for her son's death in the war against the Authority draws Lyra, now 15, into a trap. Birds mysteriously rescue her and Pan, and she makes the acquaintance of an alchemist, formerly the witch's lover.

Once Upon a Time in the North

This short novel serves as a prequel to His Dark Materials and focuses on the 24-year-old Texan aeronaut Lee Scoresby. After winning his hot-air balloon, Scoresby heads to the North, landing on the Arctic island Novy Odense, where he finds himself pulled into a dangerous conflict between the oil-tycoon Larsen Manganese, the corrupt mayoral candidate Ivan Poliakov, and his longtime enemy from the Dakota Country, Pierre McConville. The story tells of Lee and Iorek's first meeting, and of how they overcame these enemies.

The Book of Dust

The in-the-works companion to the trilogy, The Book of Dust will not continue the story, but was originally said to offer several short stories with the same characters, world, etc. Later, however, it was said it would be about Lyra when she is older, about 2 years after Lyra's Oxford, and she will go on a new adventure and learn to read the alethiometer again. The book will touch on research into Dust as well as on the portrayal of religion in His Dark Materials. Pullman has not yet[update] finished writing this work.

Future books

Siblani has also told of his hope to publish a small green book about Will:

Lyra's Oxford was a dark red book. Once Upon a Time in the North will be a dark blue book. There still remains a green book. And that will be Will's book. Eventually...

— Philip Pullman

Siblani confirmed this in an interview with two fans in August 2007.[13]

Characters

Every human surface story character from Lyra's world, including witches, has a dæmon (pronounced "demon"). A dæmon is a soul or spirit that takes the form of a creature (moth, bird, dog, monkey, snake, etc.) and is usually opposite in sex from its partner. The dæmons of children frequently change shape, but when puberty arrives the dæmon assumes a permanent form, differing from person to person. When a person dies, the dæmon dies too, and vice versa. In literature, a dæmon is usually called a "familiar." Armored bears, cliff ghasts, and other creatures do not have dæmons. An armored bear's armor is his soul.

- Lyra Belacqua, a wild, tomboyish 12-year-old girl, has grown up in the fictional Jordan College, Oxford. Although initially ignorant of the fact, Lyra is Lord Asriel's daughter. She is described as skinny with dark blonde hair and blue eyes. She prides herself on her capacity for mischief, especially her ability to lie with "bare-faced conviction". Because of her ability, Iorek Byrnison (her armored bear friend and protector) gives her the byname "Silvertongue". Lyra has the alethiometer, which answers any question when properly manipulated.

- Pantalaimon is Lyra's dæmon. Like all dæmons of children, he changes from one creature to another constantly, but when Lyra reaches puberty he assumes his permanent form, that of a pine marten. Lyra and Pantalaimon follow their father, Lord Asriel, when he travels to the newly discovered world of Cittagazze over his newly created "Bridge to the Stars."

- Will Parry, a sensible, morally conscious, highly assertive 12-year-old boy from our world. He obtains and bears the Subtle Knife. Will is very independent and responsible for his age, having looked after his mentally unstable mother for several years. He is strong for his age, and knows how to remain inconspicuous.

- The Authority is the first angel to have emerged from Dust. He controls the Church, an oppressive religious institution that symbolizes Christianity. He told the later-arriving angels that he created them and the universe, but this is a lie. Although he is one of the two primary adversaries in the trilogy—Lord Asriel is his primary opponent—he remains in the background; he makes his first and only appearance late in The Amber Spyglass. At the time of the story, the Authority has grown weak and has transferred most of his powers to his regent, Metatron. Pullman portrays him as extremely aged, fragile, and naїve, unlike his thoroughly malicious underling.

- Lord Asriel, ostensibly Lyra's uncle, later emerges as her father. He opens a rift between the worlds in his pursuit of Dust. His dream of establishing a Republic of Heaven to rival The Authority's Kingdom leads him to use his considerable power and force of will to raise a grand army from across the multiverse to rise up in rebellion against the forces of the Church.

- Marisa Coulter is the coldly beautiful, highly manipulative mother of Lyra and former lover of Lord Asriel. She serves the Church by kidnapping children for research into the nature of Dust. She has black hair, a thin build, and looks younger than she is. Initially hostile to Lyra, she belatedly realizes that she loves her daughter and seeks to protect her from agents of the Church, who want to kill Lyra.

- The Golden Monkey, Mrs. Coulter's dæmon (named Ozymandias in the BBC Radio adaptations but never named in Pullman's books) has a cruel abusive streak that reflects Coulter's character.

- Metatron, Asriel's active adversary (a proxy for the Authority) was a human being in biblical times Enoch and was later transfigured into an angel. The Authority, who claims to be immortal but really isn't, has displayed his declining health by appointing Metatron his regent, acting head of the Church. As regent, Metatron has implanted the monotheistic religions across the universes. Though an angel, he still feels human feelings, and so becomes vulnerable to the seductive advances of Marisa Coulter, who betrays him by luring him into the underworld to his death.

- Mary Malone is a physicist and former nun from the Will's world (earth). She meets Lyra during Lyra's first visit to earth. Lyra provides Mary with insight into the nature of dust. Agents of the Church force Mary to flee to the world of the mulefa. There she constructs the amber spyglass, which enables her to see the otherwise invisible (to her but not to the mulefa) dust. Her purpose is to learn why Dust, which mulefa civilization depends on, is flowing out of the universe. (Knowledge, symbolized by dust, is disappearing.) Mary relates a story of a lost love to Will and Lyra, and later packs for them a lunch containing "little red fruits". This is something her computer, "the Cave," with which Mary has managed to harness dust and obtain its counsel, instructed her to do.

- The Master of Jordan heads Jordan College at Lyra's world's Oxford University. Helped by other Jordan College employees, he is raising the supposedly (but not actually) orphaned Lyra. His big scene is in chapter 1 of The Golden Compass. There he tries unsuccessfully to poison Lord Asriel, thinking that Asriel is endangering Lyra. Lyra sees the Master put poison in a decanter of tokay wine that Asriel is expected to drink. She warns Asriel, who later "accidentally" knocks the decanter to the floor, blaming a servant for the mishap.

- Roger Parslow is the kitchen boy at Jordan College and Lyra's best friend.

- John Parry, a.k.a. Stanislaus Grumman is Will's father.

- Elaine Parry is Will Parry's mother. She became mentally ill after her husband disappeared on an expedition and has been left by Will in the care of Mrs. Cooper, Will's former piano teacher.

- The Four Gallivespians -- Lord Roke, Madame Oxentiel, Chevalier Tialys, and Lady Salmakia—are tiny people (a hand-span tall) with poisonous heel spurs. The name "Gallivespians" is a combination of (1) Gallive, a slight variation of Gullive from Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, (2) vesp, Latin for "wasp," a reference to the stinging heel spurs, and (3) ian from Lilliputian, one of the tiny people from Gulliver's Travels.

- The Palmerian Professor is a minor character presented as a joke by Pullman. His initials, PP, are those of Philip Pullman. Pullman has insinuated himself into the gathering of notables who, at the beginning of the story, have come to the Jordan College Retiring Room to hear a presentation by Lord Asriel. Pullman is a graduate of Exeter College of Oxford University. Exeter's distinctive landmark, and its oldest building, is Palmer's Tower, hence the name "Palmerian." Jordan College symbolizes Exeter, although this is not an allegorical symbol. The Palmerian Professor is the leading authority on armored bears, just as Pullman is. On his Acknowledgements page at the end of the trilogy, Pullman facetiously characterizes himself as a plagiarist who has "stolen" ideas from many literary sources. (An example of Pullman's "plagiarism" is Lord Roke and the Gallivespians, who fly around on huge dragonflies or, in Roke's case, a blue hawk. Lord Roke is, in effect, Lord of the Fliers -- alluding to William Golding's novel Lord of the Flies.) In the trilogy, Professor Jotham Santelia calls the Palmerian Professor a plagiarist. The Palmerian Professor's last name is Trelawney. In Lyra's Oxford, a sequel to the trilogy, a fold-out map shows an ad for a book by Professor P. Trelawney.

- Iorek Byrnison is a massive armoured bear. An armored bear's armour is his soul, equivalent to a human's dæmon. Iorek's armour is stolen, so he becomes despondent. With Lyra's help he regains his armour, his dignity, and his kingship over the armoured bears. In gratitude, and impressed by her cunning, he dubs her "Lyra Silvertongue". A powerful warrior and armoursmith, Iorek repairs the Subtle Knife when it shatters. He later goes to war against The Authority and Metatron.

- John Faa and Ma Costa are river "gyptians" (gypsies). Unknown to Lyra, Ma Costa was her nanny when Lyra was an infant. Faa and Costa rescue Lyra when she runs away from Mrs. Coulter. Then they take her to Iorek.

- Lee Scoresby, a rangy Texan, is a balloonist. He helps Lyra in an early quest to reach Asriel's residence in the North, and he later helps John Parry reunite with his son Will.

- Serafina Pekkala is the beautiful queen of a clan of Northern witches. Her snow-goose dæmon Kaisa, like all witches' dæmons, can travel much farther apart from her than the dæmons of humans.

- Father Gomez is a priest sent by the Church to assassinate Lyra. Balthamos, an angel watching over Lyra, kills him before he can kill Lyra.

- Balthamos is a good angel who, near the end of the story, saves Lyra's life.

- Tony Makarios is a naive boy who is lured into captivity by Mrs. Coulter. Mrs. Coulter gains Tony's confidence by offering him a delicious drink of "chocolatl" (the name for chocolate in Lyra's world). The offer, accepted by Tony, draws him into a warehouse and into captivity.

- The Mulefa are four-legged wheeled animals; they have one leg in front, one in back, and one on each side. The "wheels" are huge, round, hard seed-pods from seed-pod trees; an axle-like claw at the end of each leg grips a seed-pod. The Mulefa society is primitive.

- The Tualapi are huge, flightless birds who attack Mulefa settlements. The Tualapi sail to the settlements on tandem fore-and-aft wings that are uplifted to serve as sails. The wings symbolize the sailing ships on which early missionaries sailed to their destinations. On reaching settlements the Tualapi kill any Mulefa they can catch, eat all the food, destroy everything in sight, and then defecate everywhere.

Dæmons

One distinctive aspect of Pullman's story comes from his concept of "dæmons". In the birth-universe of the story's protagonist Lyra Belacqua, a human individual's soul[14][15] manifests itself throughout life as an animal-shaped "dæmon" that always stays near its human counterpart. Witches and some humans have entered areas where dæmons cannot physically enter; after suffering horrific separation-trauma, their dæmons can then move as far away from their humans as desired.[16]

Dæmons usually only talk to their own associated humans, but they can communicate with other humans and with other dæmons autonomously. During the childhood of its associated human, a dæmon can change its shape at will, but with the onset of adolescence it settles into a single form. The final form reveals the person's true nature and personality, implying that these stabilise after adolescence. Pullmanian society considers it "the grossest breach of etiquette imaginable"[17] for one person to touch another's dæmon — this would violate the most strict of taboos. "A human being with no dæmon is like someone without a face, or with their ribs laid open and their heart torn out: something unnatural and uncanny that belonged to the world of night-ghasts, not the waking world of sense."[18]

In some worlds, Spectres prey upon the dæmons of adults, consuming them and rendering said dæmons' humans essentially catatonic; they lose all thought and eventually fade away and die. Although in the world that this happens the humans do not have dæmons as such, but dæmon could be used to describe the humans soul or the like. Dæmons and their humans can also become separated through intercision, a process involving cutting the link between the dæmon and the human. This process can take place in a medical setting, as with the titanium and manganese guillotine used at Bolvangar, or as a form of torture used by the Skraelings. This separation entails a high mortality rate and changes both human and dæmon into a zombie-like state. Severing the link using the silver guillotine method releases tremendous amounts of unnamed energy, convertible to anbaric (electric) power.

Awards and recognition

The Amber Spyglass won the 2001 Whitbread Book of the Year award,[19] a prestigious British literary award. This is the first time that such an award has been bestowed on a book from their "children's literature" category.

The first volume, Northern Lights, won the Carnegie Medal for children's fiction in the UK in 1995.[20] In 2007, the judges of the CILIP Carnegie Medal for children's literature selected it as one of the ten most important children's novels of the previous 70 years. In June 2007 it was voted, in an online poll, as the best Carnegie Medal winner in the seventy-year history of the award, the Carnegie of Carnegies.[21][22]

The Observer cites Northern Lights as one of the 100 best novels.[23]

On 19 May 2005, Pullman attended the British Library in London to receive formal congratulations for his work from culture secretary Tessa Jowell "on behalf of the government".

On 25 May 2005, Pullman received the Swedish government's Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award for children's and youth literature (sharing it with Japanese illustrator Ryōji Arai).[24] Swedes regard this prize as second only to the Nobel Prize in Literature; it has a value of 5 million Swedish Kronor or approximately £385,000.

The trilogy came third in the 2003 BBC's Big Read, a national poll of viewers' favourite books, after The Lord of the Rings and Pride and Prejudice. At the time, only His Dark Materials and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire amongst the top five works lacked a screen-adaptation (the film version of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, which came fifth, went into release in 2005).

Influences

Sibalni has identified three major literary influences on His Dark Materials: the essay On the Marionette Theatre by Heinrich von Kleist (online at southerncrossreview.org), the works of William Blake, and, most important, John Milton's Paradise Lost, from which the trilogy derives its title.[25]

Sibalni had the stated intention of inverting Milton's story of a war between heaven and hell, such that the devil would appear as the hero.[26] In his introduction, he adapts a famous description of Milton by Blake to quip that he (Pullman) "is of the Devil's party and does know it." Pullman also referred to gnostic ideas in his description of the novels' underlying mythic structure.[27]

The Chronicles of Narnia, a series of books by C. S. Lewis, appears to have had a negative influence on Pullman's trilogy. Pullman has characterised C. S. Lewis's series as "blatantly racist", "monumentally disparaging of women", "immoral", and "evil".[28][29] However, some critics have compared the trilogy with such fantasy books as Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson and A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L'Engle as well as the Narnia series.[30][31]

Controversies

His Dark Materials has occasioned some controversy, primarily amongst some Christian groups.[32][33]

Sibalni has expressed surprise over what he perceives as a low level of criticism for His Dark Materials on religious grounds, saying "I've been surprised by how little criticism I've got. Harry Potter's been taking all the flak... Meanwhile, I've been flying under the radar, saying things that are far more subversive than anything poor old Harry has said. My books are about killing God".[34]

Some of the characters criticise institutional religion. Ruta Skadi, a witch and friend of Lyra's calling for war against the Magisterium in Lyra's world, says that "For all of [the Church's] history... it's tried to suppress and control every natural impulse. And when it can't control them, it cuts them out" (see intercision). Skadi later extends her criticism to all organised religion: "That's what the Church does, and every church is the same: control, destroy, obliterate every good feeling". By this part of the book, the witches have made reference to how they are treated criminally by the church in their worlds. Mary Malone, one of Pullman's main characters, states that "the Christian religion... is a very powerful and convincing mistake, that's all". Formerly a Catholic nun, she gave up her vows when the experience of falling in love caused her to doubt her faith. Pullman has warned, however, against equating these views with his own, saying of Malone: "Mary is a character in a book. Mary's not me. It's a story, not a treatise, not a sermon or a work of philosophy".[35] In another inversion, the tenet that the Church can absolve a penitent of sin is subverted when the priest selected to assassinate Lyra has built up sufficient penitential credit before attempting to carry out this sin for the Church.[36]

Sibalni portrays life after death very differently from the Christian concept of heaven: In the third book, the afterlife plays out in a bleak underworld, similar to the Greek vision of the afterlife, wherein harpies torment people until Lyra and Will descend into the land of the dead. At their intercession, the harpies agree to stop tormenting the dead souls, and instead receive the true stories of the dead in exchange for leading them again to the upper world. When the dead souls emerge, they dissolve into atoms and merge with the environment.

Sibalni's "Authority", though worshipped on Lyra's earth as God, emerges as the first conscious creature to evolve. Pullman makes it explicit that the Authority did not create worlds, and his trilogy does not speculate on who or what (if anything) might have done so. Members of the Church are typically displayed as zealots.[37][38]

Cynthia Grenier, in the Catholic Culture, has said: "In the world of Pullman, God Himself (the Authority) is a merciless tyrant".[39] His Church is an instrument of oppression, and true heroism consists of overthrowing both."[40] William A. Donohue of the Catholic League has described Pullman's trilogy as "atheism for kids".[41] Pullman has said of Donohue's call for a boycott, "Why don't we trust readers? [...] Oh, it causes me to shake my head with sorrow that such nitwits could be loose in the world".[42]

Sibalni has, however, found support from some other Christians, most notably from Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury (spiritual head of the Anglican church), who argues that Pullman's attacks focus on the constraints and dangers of dogmatism and the use of religion to oppress, not on Christianity itself.[43] Williams has also recommended the His Dark Materials series of books for inclusion and discussion in Religious Education classes, and stated that "To see large school-parties in the audience of the Pullman plays at the National Theatre is vastly encouraging".[44]

Sibalni has singled out certain elements of Christianity for criticism, as in the following: "I suppose technically, you'd have to put me down as an agnostic. But if there is a God, and He is as the Christians describe Him, then He deserves to be put down and rebelled against".[45] However, Pullman has also said in interviews and appearances that his argument can extend to all religions.[46][47]

Catholic Herald

In a November 2002 interview Philip Pullman was asked "What's your response to the reactions of the religious right to your work? The Catholic Herald called your books the stuff of nightmares and worthy of the bonfire." He replied: "My response to that was to ask the publishers to print it in the next book, which they did! I think it's comical, it's just laughable."[48]

Though widely reported, the Herald had not called for the book to be burned. Catholic writer Leonie Caldecott was defending J. K. Rowling and joked that there were better things for fundamentalists to burn (it was around Guy Fawkes Night).[49][50]

Adaptations

His Dark Materials has appeared in adaptation on radio, in theatre and on film.

Radio

The BBC made His Dark Materials into a radio drama on BBC Radio 4 starring Terence Stamp as Lord Asriel and Lulu Popplewell as Lyra. The play was broadcast in 2003 and is now published by the BBC on CD and cassette. In the same year, a radio drama of Northern Lights was made by RTÉ (Irish public radio).

The BBC Radio 4 version of His Dark Materials was repeated on BBC Radio 7 between 7 December 2008 to 11 January 2009. With 3 episodes in total, each episode was 2.5 hours long.

Theatre

Nicholas Hytner directed a theatrical version of the books as a two-part, six-hour performance for London's Royal National Theatre in December 2003, running until March 2004. It starred Anna Maxwell-Martin as Lyra, Dominic Cooper as Will, Timothy Dalton as Lord Asriel and Patricia Hodge as Mrs Coulter with dæmon puppets designed by Michael Curry. The play was enormously successful and was revived (with a different cast and a revised script) for a second run between November 2004 and April 2005. It has since been staged by several less known theatres in the UK, notably at the Playbox Theatre Company in Warwick (a major youth theatre company in the West Midlands)and the Theatre Royal Bath by the Young People's Theatre, which went on to receive the Bath play of the year. The play had its Irish Premiere at the O'Reilly Theatre in Dublin when it was staged by the dramatic society of Belvedere College.

A major new production was staged at Birmingham Repertory Theatre in March and April 2009, directed by Rachel Kavanaugh and Sarah Esdaile and starring Amy McAllister as Lyra. This version toured the UK and included a performance in Philip Pullman's hometown of Oxford. Philip Pullman made a cameo appearance much to the delight of the audience and Oxford media. The production finished up at West Yorkshire Playhouse in June 2009.

A student-run theatre company named Johnstone Underground Theatre (J.U.T), presented a four and a half hour stage version of the series on 23 and 24 July 2010 in Northbrook, IL. The show was composed of two acts and was heavily abridged to cope with the groups financial and time limitations. This version cut out some aspects of the series that are presented in the Subtle Knife and The Amber Spyglass such as Spectres, Gallivespians, and all of Dr. Mary Malone's adventures. The second act was the combined version of these two books. The first act presented the majority of the events in The Golden Compass faithfully.

Film

New Line Cinema released a film adaptation, titled The Golden Compass, on 7 December 2007. Directed by Chris Weitz, the production had a mixed reception, and though worldwide sales were strong, its United States take underwhelmed the studio's hopes.[51]

The filmmakers obscured the books' explicitly Biblical character of the Authority so as to avoid offending some viewers, though Weitz declared that he would not do the same for the hoped-for sequels. "Whereas The Golden Compass had to be introduced to the public carefully", he said, "the religious themes in the second and third books can't be minimised without destroying the spirit of these books. ...I will not be involved with any 'watering down' of books two and three, since what I have been working towards the whole time in the first film is to be able to deliver on the second and third".[52] In May 2006, Pullman said of a version of the script that "all the important scenes are there and will have their full value";[53] in March 2008, he said of the finished film that "a lot of things about it were good.... Nothing can bring out all that's in the book. There are always compromises".Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).

Terminology

Further reading

- Frost, Laurie; et al. (2006). The Elements of His Dark Materials: A Guide to Phillip Pullman's trilogy. Buffalo Grove, IL: Fell Press. ISBN 0-9759430-1-4. OCLC 73312820.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - Gribbin, John and Mary (2005). The Science of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials. Knopf Books for Young Readers. ISBN 0-375-83144-4.

- Lenz, Millicent and Carole Scott (2005). His Dark Materials Illuminated: Critical Essays on Phillip Pullman's Trilogy. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3207-2.

- Raymond-Pickard, Hugh (2004). The Devil's Account: Philip Pullman and Christianity. London: Darton, Longman & Todd. ISBN 978-0232525632.

- Squires, Claire (2003). Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials Trilogy: A Reader's Guide. New York, N.Y.: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-1479-6.

- Squires, Claire (2006). Philip Pullman, Master Storyteller: A Guide to the Worlds of His Dark Materials. New York, N.Y.: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1716-9. OCLC 70158423.

- Tucker, Nicholas (2003). Darkness Visible: Inside the World of Philip Pullman. Cambridge: Wizard Books. ISBN 978-1840464825. OCLC 52876221.

- Wheat, Leonard F. (2008). Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials: A Multiple Allegory: Attacking Religious Superstition in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and Paradise Lost. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1591025894. OCLC 152580912.

- Yeffeth, Glenn (2005). Navigating the Golden Compass: Religion, Science and Daemonology in His Dark Materials. Dallas: Benbella Books. ISBN 1-932100-52-0.

References

Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (August 2011) |

- ^ a b Robert Butler (3 December 2007). "An Interview with Philip Pullman". The Economist. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- ^ Freitas, Donna; King, Jason Edward (2007). Killing the imposter God: Philip Pullman's spiritual imagination in His Dark Materials. San Francisco, CA: Wiley. pp. 68–9. ISBN 978-0-7879-8237-9.

- ^ "The Man Behind the Magic: An Interview with Philip Pullman". Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ Rosin, Hanna (1 December 2007). "How Hollywood Saved God". The Atlantic Monthly. The Atlantic Monthly Group. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (8 December 2007). "What Would Jesus See?". TIME. Time Inc. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". BridgeToTheStars.net. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- ^ Philip Pullman, The Subtle Knife (New York: Knopf, 1997), 90, 238.

- ^ Squires (2003: 61): "Religion in Lyra's world...has similarities to the Christianity of 'our own universe', but also crucial differences…[it] is based not in the Catholic centre of Rome, but in Geneva, Switzerland, where the center of religious power, narrates Pullman, moved in the Middle Ages under the aegis of John Calvin.")

- ^ Miller, Laura (26 December 2005). "Far From Narnia". The New Yorker. 2011 Condé Nast Digital. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ Northern Lights p. 31: "Ever since Pope John Calvin had moved the seat of the papacy to Geneva...the Church's power over every aspect of life had been absolute.

- ^ Wheat, Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials, 160-61.

- ^ Ibid., 229.

- ^ Hisdarkmaterials.org

- ^ "...Lyra had come to realise...the three-part nature of human beings. ... The Catholic Church... wouldn't use the word dæmon, but St Paul talks about spirit and soul and body." Amber Spyglass pp 462–63

- ^ "Pullman's Jungian concept of the soul": Lenz (2005: 163)

- ^

Pullman, Philip (2007) [2000]. The Amber Spyglass. His Dark Materials. New York: Random House, Inc. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-440-23815-7.

There's a region of our north land, a desolate, abominable place... No dæmons can enter it. To become a witch, a girl must cross it alone and leave her dæmon behind. You know the suffering they must undergo. But having done it... [their dæmon] can roam free, and go to far places.

- ^ Pullman, Philip (2007) [1995]. The Northern Lights. His Dark Materials. London: Scholastic UK Ltd. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-407104-05-8.

- ^ Pullman, Philip (2007) [1995]. The Northern Lights. His Dark Materials. London: Scholastic UK Ltd. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-407104-05-8. Chapter 13

- ^ "Children's novel triumphs in 2001 Whitbread Book Of The Year" (Press release). 23 January 2002. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ "Living Archive: Celebrating the Carnegie and Greenaway Winners". CarnegieGreenaway.org.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ Pauli, Michelle (21 June 2007). "Pullman wins 'Carnegie of Carnegies'". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "70 years celebration the publics favourite winners of all time".

- ^

The Guardian. London http://blogs.guardian.co.uk/observer/archives/2005/05/11/the_best_novels_ever_version_12.html. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ SLA – Philip Pullman receives the Astrid Lindgren Award

- ^ Fried, Kerry. "Darkness Visible: An Interview with Philip Pullman". Amazon.com. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Mitchison, Amanda (3 November 2003). "The art of darkness". Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Oborne, Peter (17 March 2004). "The Dark Materials debate: life, God, the universe..." Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ezard, John (3 June 2002). "Narnia books attacked as racist and sexist". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ Abley, Mark (4 December 2007). "Writing the book on intolerance". The Star. Toronto. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Crosby, Vanessa. "Innocence and Experience: The Subversion of the Child Hero Archetype in Philip Pullman's Speculative Soteriology" (PDF). University of Sydney. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ^ Miller, Laura (26 December 2005). "Far From Narnia: Philip Pullman's secular fantasy for children". The New Yorker. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ^ Overstreet, Jeffrey (20 February 2006). "Reviews:His Dark Materials". Christianity Today. Archived from the original on 18 March 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ^ Thomas, John (2006). "Opinion". Librarians' Christian Fellowship. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ^ Meacham, Steve (13 December 2003). "The shed where God died". Sydney Morning Herald Online. Retrieved 13 December 2003.

- ^

"A dark agenda? Interview with Philip Pullman". surefish.co.uk. November, 2002. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lenz; Scott (2005: 97)

- ^

Ebbs, Rachael. "Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials: An Attack Against Christianity or a Confirmation of Human Worth?". BridgeToTheStars.Net. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Greene, Mark. "Pullman's Purpose". The London Institute for Contemporary Christianity. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Grenier, however, misrepresents the Authority: Pullman actually presents the Authority as a frail old man whose power the angel Metatron has taken.

- ^

Grenier, Cynthia (2001). "Philip Pullman's Dark Materials". The Morley Institute Inc. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Donohue, Bill (9 October 2007). ""The Golden Compass" Sparks Protest". The Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- ^ David Byers (27 November 2007). "Philip Pullman: Catholic boycotters are 'nitwits'". The Times. UK. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- ^ Petre, Jonathan (10 March 2004). "Williams backs Pullman". Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Rowan, Williams (10 March 2004). "Archbishop wants Pullman in class". BBC News Online. Retrieved 10 March 2004.

- ^ "Sympathy for the Devil by Adam R. Holz". Plugged In Online. Retrieved 16 December 2007. [dead link]

- ^ Spanner, Huw (13 February 2002). "Heat and Dust". ThirdWay.org.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2007. [dead link]

- ^ Bakewell, Joan (2001). "Belief". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on 11 September 2004. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ "A dark agenda?"

- ^ "Phillip Pulman: 'The Big Read' and the big lie"

- ^ "Phillip Pulman: 'The Stuff of Nightmares"

- ^ Dawtrey, Adam (13 March 2008). "'Compass' spins foreign frenzy". Variety.com. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

{{cite news}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "'Golden Compass' Director Chris Weitz Answers Your Questions: Part I by Brian Jacks". MTV Movies Blog. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ Pullman, Philip (May 2006). "May message". Retrieved 24 September 2008.

And the latest script, from Chris Weitz, is truly excellent; I know, because I`ve just this morning read it. I think it`s a model of how to condense a story of 400 pages into a script of 110 or so. All the important scenes are there and will have their full value.

External links

- BridgetotheStars.net fansite for His Dark Materials and Philip Pullman

- HisDarkMaterials.org His Dark Materials fansite

- HisDarkMaterials.com, publisher Random House's His Dark Materials website

- Cittagazze.com, the His Dark Materials, a French fansite

- Scholastic: His Dark Materials, the UK publisher's website

- Randomhouse: His Dark Materials, the U.S. publisher's website

- The BBC's His Dark Materials pages

- The Archbishop of Canterbury and Philip Pullman in conversation, from "The Daily Telegraph"