House of Borgia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Borgia Borja | |

|---|---|

| Noble house | |

| |

| Country | Spain, Italy, France |

| Founded | 1455 |

| Founder | Alfons de Borja |

| Current head | Rodrigo Borja Cevallos |

| Final ruler | Pope Alexander VI |

| Titles |

|

| Deposition | 1672 |

The House of Borgia (/ˈbɔːrʒə/; Italian: [ˈbɔrdʒa]; Template:Lang-es [ˈborxa]; Template:Lang-va [ˈbɔɾdʒa]) family became prominent during the Renaissance in Italy. They were from Valencia, the surname being a toponymic from Borja, then in the Crown of Aragon, in Spain.

The Borgias became prominent in ecclesiastical and political affairs in the 15th and 16th centuries, producing two popes: Alfons de Borja, who ruled as Pope Callixtus III during 1455–1458, and Rodrigo Lanzol Borgia, as Pope Alexander VI, during 1492–1503.

Especially during the reign of Alexander VI, they were suspected of many crimes, including adultery, incest, simony, theft, bribery,[citation needed] and murder (especially murder by arsenic poisoning).[1] Because of their grasping for power, they made enemies of the Medici, the Sforza, and the Dominican friar Savonarola, among others. They were also patrons of the arts who contributed to the Renaissance.

History

Early history

The Borja or Borgia emerged from Valencia in the Crown of Aragon, Spain. There were numerous unsubstantiated claims that the family was of Jewish origin. These underground rumours were propagated by, among others, Giuliano della Rovere, and the family was frequently described as marranos by political opponents. The rumours have persisted in popular culture for centuries, listed in the Semi-Gotha of 1912.[2][3][4]

Alfons

Alfons de Borja, later known as Pope Callixtus III (1378–1458), was born to Francina Llançol and Domingo de Borja in La Torreta, Canals, which was then situated in the Kingdom of Valencia.

Alfons de Borja was a professor of law at the University of Lleida, then a diplomat for the Kings of Aragon before becoming a cardinal. He was elected Pope Callixtus III in 1455, at an advanced age, as a compromise candidate and reigned as Pope for just 3 years.

Rodrigo

Rodrigo Borgia (1431–1503), one of Alfonso’s nephews, was born in Xàtiva, also in the Kingdom of Valencia to Isabel de Borja i Cavanilles and Jofré Llançol i Escrivà. He studied law at Bologna and was appointed as cardinal by his uncle, Alfonso Borgia, Pope Callixtus III. He was elected Pope in 1492, taking the regnal name Alexander VI. While a cardinal, he maintained a long-term illicit relationship with Vanozza dei Cattanei, with whom he had four children: Giovanni; Cesare; Lucrezia; and Gioffre. Rodrigo also had children by other women, including one daughter with his mistress, Giulia Farnese.

As Alexander VI, Rodrigo was recognized as a skilled politician and diplomat, but was widely criticized during his reign for his over-spending, sale of Church offices (simony), lasciviousness, and nepotism. As Pope, he struggled to acquire more personal and papal power and wealth, often ennobling and enriching the Borgia family directly. He appointed his son, Giovanni, as captain-general of the papal army, his foremost military representative, and established another son, Cesare, as a cardinal. Alexander used the marriages of his children to build alliances with powerful families in Italy and Spain. At the time, the Sforza family, which comprised the Milanese faction, was one of the most powerful in Europe, so Alexander united the two families by marrying Lucrezia to Giovanni Sforza. He also married Gioffre, his youngest son from Vannozza, to Sancha of Aragon of the Crown of Aragon and Naples. He established a second familial link to the Spanish royal house through Giovanni's marriage during what was a period of on-again/off-again conflict between France and Spain over the Kingdom of Naples.

Pope Alexander VI died in Rome in 1503 after contracting a disease, generally believed to have been malaria. Two of Alexander's successors, Sixtus V and Urban VIII, described him as one of the most outstanding popes since St. Peter.[5]

Cesare

Cesare was Rodrigo Borgia's second son with Vannozza dei Cattanei. Cesare's education was precisely planned by his father: he was educated by tutors in Rome until his 12th birthday. He grew up to become a charming man skilled at war and politics.[6] He studied law and the humanities at the University of Perugia, then went to the University of Pisa to study theology. As soon as he graduated from the university, his father made him a cardinal.

Cesare was suspected of murdering his brother Giovanni, but there is no clear evidence to confirm this. However, Giovanni’s death cleared the path for Cesare to become a layman and gain the honors his brother received from their father, Pope Alexander VI.[7] Although Cesare had been a cardinal, he left the holy orders to gain power and take over the position Giovanni once held: a condottiero. He was finally married to French princess Charlotte d'Albret.

After Alexander’s death in 1503, Cesare affected the choice of a next Pope. He needed a candidate who would not threaten his plans to create his own principality in Central Italy. Cesare’s candidate (Pius III) did become Pope, but he died a month after the selection. Cesare was now forced to support Giuliano della Rovere. The cardinal promised Cesare that he could keep all of his titles and honors. Later, della Rovere betrayed him and became his fiercest enemy.

Cesare died in 1507, at Viana Castle in Navarre, Spain while besieging the rebellious army of Count de Lerín. The castle was held by Louis de Beaumont at the time it was besieged by Cesare Borgia and King John's army of 10,000 men in 1507. In order to attempt to breach the extremely strong, natural fortification of the castle, Cesare counted on a desperate surprise attack. He was killed during the battle, in which his army failed to take the castle.

Lucrezia

Lucrezia was born in Subiaco, Italy to Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia and Roman mistress Vanozza Catanei. Before the age of 13, she was engaged to two Spanish princes. After her father became Pope she was married to Giovanni Sforza in 1493 at the age of 13. It was a typical political marriage to improve Alexander's power; however, when Pope Alexander VI did not need the Sforzas any more, the marriage was annulled in 1497, on the dubious grounds that it had never been consummated.

Shortly afterwards she was involved in a scandal involving her alleged relationship with a Pedro Calderon, a Spaniard generally known as Perotto. His body was found in the Tiber on February 14, 1498 along with the body of one of Lucrezia's ladies. It is likely that Cesare had them killed as an affair would have damaged the negotiations being conducted for another marriage. During this time rumors were also spread suggesting that a child born at this time, Giovanni Borgia, also known as the Infans Romanus (child of Rome) was Lucrezia's.[8]

Lucrezia’s second marriage, to wealthy young Prince Alfonso of Aragon, allowed the Borgias to form an alliance with another powerful family. However, this relationship did not last long either. Cesare wished to strengthen his relations with France and completely break with the Kingdom of Naples. As Alfonso's father was the ruler of the Kingdom of Naples, the young husband was in great danger. Although the first attempt at murder did not succeed, Alfonso was eventually strangled in his own quarters.

Lucrezia's third and final husband was Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara. After her father died in 1503, she lived a life of freedom in Ferrara with her husband and children.[9] Unfortunately, her pregnancies were difficult and she lost several babies after birth. She died in 1519, 10 days after the birth and death of her last child, Isabella Maria. She was buried in a tomb with Isabella and Alfonso.

Lucrezia was a budding capitalist entrepreneur, leveraging her own capital by obtaining marshland at negligible cost and then investing in massive reclamation enterprises. She also raised livestock and rented parts of her newly arable land for short terms, nearly doubling her annual income in the process.[10]

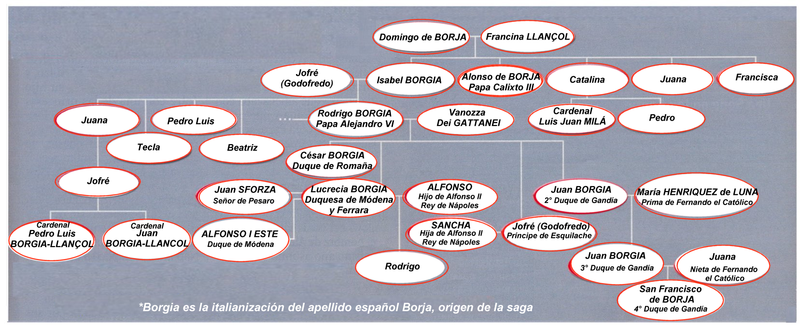

Family tree

Other notable Borjas/Borgias

The Borgian era, or the time period when the Borgia family had its greatest influence, started in the early 16th century[citation needed], about the time of the death of Lucrezia in 1519. The Borgia family had influence during the age of the Renaissance and the beginning of the Age of Discovery. This was the era of many artists, writers and rulers who have influenced the modern age.

Gioffre Borgia (1482–1516), son of Pope Alexander VI and younger brother of Cesare Borgia and Lucrezia Borgia, married Sancia (Sancha) of Aragon, daughter of Alfonso II of Naples, obtaining as dowry both the Principality of Squillace (1494) and the Duchy of Alvito (1497).

Although Gioffre was deprived of Alvito after the death of Sancia in 1506, he managed to retain Squillace. He subsequently married Maria de Mila, and passed it on to their son Francesco Borgia.

The Borgia Princes were: Gioffre, Francesco, Giovanni, Pietro and finally Anna e Donna Antonia Borgia D’Aragona on whose death, in 1735, it passed to Bourbon Kings of the Two Sicilies. Living either in Naples or Spain the Borgias ruled their fief through governors.

Not all the Borgias were corrupt or violent. Saint Francis Borgia (1510–1572), a great-grandson of Pope Alexander VI, did not follow his relatives. He had fathered a number of children and after his wife died, Francisco determined to enter the Society of Jesus, recently formed by Saint Ignatius of Loyola and became a highly effective organizer of the still new order. His efforts were effective, as the Church canonized the Jesuit Francisco on 20 June 1670.[11]

Another Borgian who lived after the Borgian era was cardinal Gaspar de Borja y Velasco (1580–1645). Unlike many of his relatives, Gaspar preferred to use the Spanish spelling of Borgia: Borja. He was born at Villalpando in Spain. He was related to both Pope Callixtus III and Pope Alexander VI, and some historians believe that Gaspar wished, like his relatives, to become Pope. He served as Primate of Spain, Archbishop of Seville, and Archbishop and Viceroy of Naples.

Controversies

Rodrigo

It is reported that under Alexander VI's rule the Borgias hosted orgies in the Vatican palace. The "Banquet of Chestnuts" is considered one of the most disreputable balls of this kind. Johann Burchard reports that fifty courtesans were in attendance for the entertainment of the banquet guests.[12] It is alleged not only was the Pope present, but also two of his children, Lucrezia and Cesare. However other researchers, such as Monsignor Peter de Roo (1839–1926), have rejected the rumors of the "fifty courtesans" as being at odds with Alexander VI's essentially decent but much maligned character.[13]

Lucrezia and Cesare

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2013) |

Some historians say that Cesare Borgia murdered his brother Giovanni Borgia, 2nd Duke of Gandia; however there is no clear evidence that he actually did.

There is also the case of Perotto, Lucrezia's lover. When Cesare found out about Lucrezia’s pregnancy, he was so furious that he had the father of the child murdered. The body of Perotto (a young chamberlain, the father of the child) was fished out of the Tiber. Also, the body of a chambermaid was found in the river; she had apparently been murdered for giving the lovers a chance to meet in secret. Both murders are believed to have been commissioned by Cesare.[citation needed]

Lucrezia was rumored to be a notorious poisoner and she became famous for her skill at political intrigue. However, recently historians have started to look at her in a more positive light: she is often seen as a victim of her family’s deceptions.[14]

Portraits of the Borjas and Borgias

-

Alfons de Borja

Pope Callixtus III -

Rodrigo Borgia

Pope Alexander VI, father of Cesare, Giovanni, Lucrezia and Gioffre. -

Lucrezia Borgia

Duchess of Ferrara and Modena

In popular culture

The Borgias were infamous in their time, and have inspired numerous references in popular culture, including novels, plays, operas, comics, films, television series and video games.

- The Prince (1513) by Niccolò Machiavelli

- Assassin's Creed Brotherhood (2010) by Ubisoft

- Predator: Concrete Jungle (2005) by Eurocom

- The Borgias (1802) by Alexandre Dumas, père[15]

- Borgia by Michel Zevaco

- The Banner of the Bull (1915) by Rafael Sabatini

- Then and Now (1946) by W. Somerset Maugham

- Prince of Foxes (1947) by Samuel Shellabarger

- The Borgia Testament (1948) by Nigel Balchin

- The Scarlet City (1952) by Hella Haasse

- Madonna of the Seven Hills (1958) by Jean Plaidy

- Light on Lucrezia (1958) by Jean Plaidy

- Francesca (1977) by Valentina Luellen

- City of God: A Novel of the Borgias (1979) by Cecelia Holland[16]

- The Antipope (1981) by Robert Rankin

- A Matter of Taste (1990) by Fred Saberhagen

- The Family (2001) by Mario Puzo

- Mirror Mirror (2003) by Gregory Maguire

- The Borgia Bride (2005) by Jeanne Kalogridis

- Queen of the Slayers (2005) by Nancy Holder

- The Medici Seal (2006) by Theresa Breslin

- Cantarella (2001–2010) by You Higuri (manga)

- Cesare (2005-) by Fuyumi Soryo (manga)

- Lucrezia Borgia (1833) by Victor Hugo (play)

- Lucrezia Borgia (1833) by Gaetano Donizetti (opera)

- Prince of Foxes (1949), starring Orson Welles

- Bride of Vengeance (1949), starring Paulette Goddard, John Lund, Macdonald Carey

- Contes immoraux, (1974) French film by Walerian Borowczyk

- Los Borgia (2006), Spanish film by Antonio Hernández

- The Conclave (2006), film by Paul Donovan

- The Borgias (1981), BBC Two TV miniseries

- Borgia (2011), Canal + TV series

- Borgia (2011), comic by Alejandro Jodorowsky and Milo Manara

- The Borgias (2011), Showtime TV series[17]

- The Assassin's Creed series[18]

See also

- Grandee of Spain

- List of popes from the Borgia family

- Borgia castles

- Route of the Borgias

- Monastery of Sant Jeroni de Cotalba

Notes

- ^ Arsenic: A Murderous History. Dartmouth Toxic Metals Research Program, 2009

- ^ The Menorah journal, Volumes 20-23, Intercollegiate Menorah Association, 1932, page 163

- ^ The Borgias: or, At the feet of Venus, Vicente Blasco Ibáñez, P. Dutton & Co. Inc., 1930, pages 242, 313

- ^ Lucrezia Borgia: Life, Love and Death in Renaissance Italy, by Sarah Bradford

- ^ Mallett, M. The Borgias (1969) Granada edition. 1981. p. 9.

- ^ "Francis Borgia (1510–1572)". London: Thames & Hudson. 2006.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Najemy, John (September 2013). Machiavelli and Cesare Borgia: A Reconsideration of Chapter 7 of The Prince (Volume 75 Issue 4 ed.). Review of politics. pp. 539–556.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Bradford, Sarah (2005). Lucrezia Borgia: Life, Love and Death in Renaissance Italy (Reprint ed.). Penguin. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0143035954.

- ^ "Borgia, Lucrezia (1480–1519)". The Penguin Biographical Dictionary of Women. London: Penguin. 1998.

- ^ Ghirardo, Diane Yvonne (Spring 2008). "Lucrezia Borgia as Entrepreneur". Renaissance Quarterly. 61 (1): 53–91.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Francis Borgia (1510–1572)". Who's Who in Christianity. London: Routledge. 2001.

- ^ Johann Burchard, Pope Alexander VI and His Court: Extracts from the Latin Diary of Johannes Burchardus, 1921, F.L. Glaser, ed., New York, N.L. Brown, pp. 154-155.[1]

- ^ In 5 volumes totaling nearly 3 thousand pages, and including many unpublished documents,* Msgr. de Roo labors to defend his thesis that pope Alexander, far from being a monster of vice (as he has so often been portrayed) was, on the contrary, "a man of good moral character and an excellent Pope." Material, vol. 1, preface, xi. [2] [3]

* "[Peter de Roo] must have devoted to his task many years of research among the Vatican archives and elsewhere. As he tells us himself in a characteristic passage: "We continued our search after facts and proofs from country to country, and spared neither labour nor money in order to thoroughly investigate who was Alexander VI., of what he had been accused, and especially what he had done." Whether all this toil has been profitably expended is a matter upon which opinions are likely to differ. But we must in any case do Mgr. de Roo the justice of admitting that he has succeeded in compiling from original and often unpublished sources a much more copious record of the pontiff's creditable activities than has ever been presented to the world before." -- Pope Alexander VI and His Latest Biographer, in The Month, April, 1925, Volume 145, p. 289.[4] - ^ Lucrezia Borgia: A Biography. Rachel Erlanger, 1978

- ^ http://www.fullbooks.com/The-Borgias1.html

- ^ Maclaine, David. "City of God by Cecelia Holland". Historicalnovels.info. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ Donahue, Deirdre (24 March 2011). "Back in time and in crime with Borgias". Life.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Snider, Mike. "'Assassin' is back with 'Brotherhood'". USA Today.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)

References

- Fusero, Clemete. The Borgias. New York, Praeger Publishers, 1966.

- Grun, Bernard. The Timetables of History. New York, Simon and Schusters, 1946, pp. 218, 220, 222.

- Hale, John R. Renaissance. New York, Time-Life Books, 1965, p. 85.

- "Mad Dogs and Spaniards: An Interview with Cesare Borgia." World and Image, 1996.

- Rath, John R. "Borgia." World Book Encyclopedia. 1994 edition. World Book Inc., 1917, pp. 499–500.

- Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume 1. (Old Catholic Encyclopedia) New York, Robert Appleton Company (a.k.a. The Encyclopedia Press), 1907.

- Duran, Eulàlia: The Borja Family: Historiography, Legend and Literature

External links

- Centropolis.homestead_Library

- Template:Es icon Borja o Borgia

- Template:Es icon Francisco Fernández de Bethencourt - Historia Genealógica y Heráldica Española, Casa Real y Grandes de España, tomo cuarto

- Template:Es icon Una rama subsistente del linaje Borja en América española, por Jaime de Salazar y Acha, Académico de Número de la Real Academia Matritense de Heráldica y Genealogía

- Template:Es icon Boletín de la Real Academia Matritense de Heráldica y Genealogía

- Template:Es icon La familia Borja: Religión y poder. Entrevista a Miguel Batllori

- Template:Es icon La mirada sobre los Borja (Notas críticas para un estado de la cuestión)

- The Borja Family: Historiography, Legend and Literature by Eulàlia Duran, Institut d’Estudis Catalans

- History of the Borgia Family

- Institut Internacional d'Estudis Borgians