Ishihara test

| Color perception test | |

|---|---|

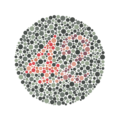

Example of an Ishihara color test plate. The number "74" should be clearly visible to viewers with normal color vision. Viewers with dichromacy or anomalous trichromacy may read it as "21", and viewers with monochromacy may see nothing. | |

| Specialty | ophthalmology |

| ICD-9-CM | 95.06 |

| MeSH | D003119 |

The Ishihara test is a color perception test for red-green color deficiencies, the first in a class of successful color vision tests called pseudo-isochromatic plates ("PIP"). It was named after its designer, Dr. Shinobu Ishihara, a professor at the University of Tokyo, who first published his tests in 1917.[1]

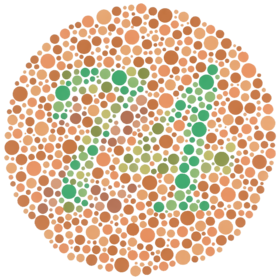

The test consists of a number of colored plates, called Ishihara plates, each of which contains a circle of dots appearing randomized in color and size.[2] Within the pattern are dots which form a number or shape clearly visible to those with normal color vision, and invisible, or difficult to see, to those with a red-green color vision defect. Other plates are intentionally designed to reveal numbers only to those with a red/green color vision deficiency, and be invisible to those with normal red/green color vision. The full test consists of 38 plates, but the existence of a severe deficiency is usually apparent after only a few plates. There is also an Ishihara test consisting 10, 14 or 24 test plates.[3]

Plates

The plates make up several different test designs:[4]

- Demonstration plate (plate number one, typically the numeral "16"); designed to be visible by all persons, whether normal or color vision deficient. For demonstration purposes only, and usually not considered in making a score for screening purposes.

- Transformation plates: individuals with color vision defect should see a different figure from individuals with normal color vision.

- Vanishing plates: only individuals with normal color vision could recognize the figure.

- Hidden digit plates: only individuals with color vision defect could recognize the figure.

- Diagnostic plates: intended to determine the type of color vision defect (protanopia or deuteranopia) and the severity of it.

-

Ishihara Plate No. 1 (12)

-

Ishihara Plate No. 13 (6)

-

Ishihara Plate No. 19 (Nothing (hidden digit plate); Red-Green deficiency sees 2)

-

Ishihara Plate No. 23 (42)

History

Born in 1879 to a family in Tokyo, Dr. Shinobu Ishihara began his education at the Imperial University where he attended on a military scholarship.[5] Ishihara had just completed his graduate studies in ophthalmology in Germany when war broke out in Europe and World War I had begun. While holding a military position related to his field, he was given the task of creating a color blindness test. Ishihara studied existing tests and combined elements of the Spilling test with the concept of pseudo-isochromaticism to produce an improved, more accurate and easier to use test. [medical citation needed]

Test procedures

Being a printed plate, the accuracy of the test depends on using the proper lighting to illuminate the page. A "daylight" bulb illuminator is required to give the most accurate results, of around 6000-7000K temperature (ideal: 6500K, Color Rendering Index (CRI) >90), and is required for military color vision screening policy. Fluorescent bulbs are many times used in school testing, but the color of fluorescent bulbs and their CRI can vary widely. Incandescent bulbs should not be used, as their low temperature (yellow-color) give highly inaccurate results, allowing some color vision deficient persons to pass.

Proper testing technique is to give only three seconds per plate for an answer, and not allow coaching, touching or tracing of the numbers by the subject. The test is best given in random sequence, if possible, to reduce the effectiveness of prior memorization of the answers by subjects. Some pseudo-isochromatic plate books have the pages in binders, so the plates may be rearranged periodically to give a random order to the test.

Since its creation, the Ishihara Color Blindness Test has become commonly used worldwide because of its easy use and high accuracy. In recent years, the Ishihara test has become available online in addition to its original paper version. Though both media use the same plates, they require different methods for an accurate diagnosis.

Occupational screening

The United States Navy uses the Ishihara plates (and alternatives) for color vision screening. The current passing score is 12 correct of 14 red/green test plates (not including the demonstration plate). Research has shown that scores below twelve indicate color vision deficiency, and twelve or more correct indicate normal color vision, with an 97% sensitivity and 100% specificity. The sensitivity of the Ishiara varies by the number of plates allowed to pass, which can vary by the institution policy. Sensitivity also may be influenced by test administration (strength of lighting, time allowed to answer) and testing errors (coaching by administrators, smudges or marks made upon the plates).

Alternatives

A number of pseudoisochromatic plates other than the Ishihara are commercially available, both printed versions and pseudo-isochromatic computerized software, designed for calibrated monitors and tablets. Computerized versions have been shown to be higher sensitivity and specificity than the printed Ishihara plates, due to lack of administration errors. Computerized tests have the additional advantage of not require special external light bulbs for illuminating the images, and have objective printouts of results, further reducing transcription errors.[medical citation needed]

References

- ^ S. Ishihara, Tests for color-blindness (Handaya, Tokyo, Hongo Harukicho, 1917).

- ^ Kindel, Eric. "Ishihara". Eye Magazine. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ http://www.dfisica.ubi.pt/~hgil/p.v.2/Ishihara/Ishihara.24.Plate.TEST.Book.pdf

- ^ Fluck, Daniel. "Color Blindness Tests". Colblinder. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ "Whonamedit - dictionary of medical eponyms". www.whonamedit.com. Retrieved 2015-08-12.

External links

- Ishihara color test information

- The Ishihara Color Blindness Test

- Test of color blindness with the indication of the weaknesses in various colors, quantifies green red blue deficiency (ISHIHARA test alternative)

- Flash animated Ishihara color blindness test