Kitsch

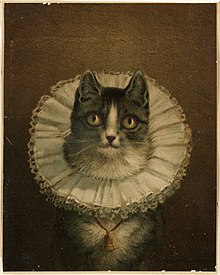

Kitsch (/ˈkɪtʃ/; loanword from German, also called cheesiness and tackiness) is a low-brow style of mass-produced art or design using popular or cultural icons. The word was first applied to artwork that was a response to certain divisions of 19th-century art with aesthetics that favored what later art critics would consider to be exaggerated sentimentality and melodrama. Hence, 'kitsch art' is closely associated with 'sentimental art'. Kitsch is also related to the concept of camp, because of its humorous and ironic nature.

To brand visual art as "kitsch" is generally pejorative, as it implies that the work in question is gaudy, or that it deserves a solely ornamental and decorative purpose rather than amounting to a work of true artistic merit. The chocolate box artist Thomas Kinkade (1958–2012), whose idyllic landscape scenes were often lampooned by art critics as "maudlin" and "schmaltzy," is considered a leading example of contemporary kitsch.[1][2][3]

The term is also sometimes applied to music.

History

As a descriptive term, kitsch originated in the art markets of Munich in the 1860s and the 1870s, describing cheap, popular, and marketable pictures and sketches.[4] In Das Buch vom Kitsch (The Book of Kitsch), Hans Reimann defines it as a professional expression "born in a painter's studio".

The study of kitsch was done almost exclusively in German until the 1970s, with Walter Benjamin being an important scholar in the field.[5]

Hermann Broch argues that the essence of kitsch is imitation: kitsch mimics its immediate predecessor with no regard to ethics—it aims to copy the beautiful, not the good.[6] According to Walter Benjamin, kitsch is, unlike art, a utilitarian object lacking all critical distance between object and observer; it "offers instantaneous emotional gratification without intellectual effort, without the requirement of distance, without sublimation".[5]

Kitsch is less about the thing observed than about the observer. According to Roger Scruton, "Kitsch is fake art, expressing fake emotions, whose purpose is to deceive the consumer into thinking he feels something deep and serious."[7]

Uses

Art

The Kitsch Movement is an international movement of classical painters, founded[clarification needed] in 1998 upon a philosophy proposed by Odd Nerdrum[8] and later clarified in his book On Kitsch[9] in cooperation with Jan-Ove Tuv and others, incorporating the techniques of the Old Masters with narrative, romanticism, and emotionally charged imagery.

According to Whitney Rugg, "Norman Rockwell's Saturday Evening Post magazine covers epitomize American World War II-era kitsch..."[10]

Music

The kitsch aesthetic can also be found in indie music, especially lo-fi which utilizes the aesthetic to create a product that feels somewhat quirky and unrefined. The aesthetic is commonly used to separate the indie sound from that of the more refined and well produced sound of mainstream music.[citation needed]

Sometimes the revival of retro music styles considered "cheesy" such as 80's Italo-Disco produced on new instruments is referred to as kitsch.[11]

Popular culture

Scruton identifies the Barbie doll as an example of kitsch.[7]

See also

References

- ^ Orlean, Susan (April 8, 2012). "Thomas Kinkade: Death of a Kitsch Master". The New Yorker. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ Mike Swift, Painter Thomas Kinkade faced turmoil during his final years, San Jose Mercury News, April 8, 2012, accessed April 8, 2012.

- ^ Perl, Jed (14 July 2011). "Bullshit Heaven". tnr.com. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- ^ Calinescu, Matei. Five Faces of Modernity. Kitsch, p. 234.

- ^ a b Menninghaus, Winfried (2009). "On the Vital Significance of 'Kitsch': Walter Benjamin's Politics of 'Bad Taste'". In Andrew Benjamin (ed.). Walter Benjamin and the Architecture of Modernity. Charles Rice. re.press. pp. 39–58. ISBN 9780980544091.

- ^ Broch, Hermann (2002). "Evil in the Value System of Art". Geist and Zeitgeist: The Spirit in an Unspiritual Age. Six Essays by Hermann Broch. Counterpoint. pp. 13–40. ISBN 9781582431680.

- ^ a b Scruton, Roger. "A Point of View: The strangely enduring power of kitsch", BBC News Magazine, December 12, 2014

- ^ E.J. Pettinger [1] "The Kitsch Campaign" [Boise Weekly], December 29, 2004.

- ^ Dag Solhjell and Odd Nerdrum. On Kitsch, Kagge Publishing, August 2001, ISBN 8248901238.

- ^ Rugg, Whitney. "Kitsch", Theories of Media, University of Chicago

- ^ Dolan, Emily (2010). "'...This little ukulele tells the truth': indie pop and kitsch authenticity". Popular Music. 29 (3): 457–469. doi:10.1017/s0261143010000437.

Further reading

- Adorno, Theodor (2001). The Culture Industry. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25380-2

- Botz-Bornstein, Thorsten (2008). "Wabi and Kitsch: Two Japanese Paradigms" in Æ: Canadian Aesthetics Journal 15.

- Braungart, Wolfgang (2002). "Kitsch. Faszination und Herausforderung des Banalen und Trivialen". Max Niemeyer Verlag. ISBN 3-484-32112-1/0083-4564.

- Cheetham, Mark A (2001). "Kant, Art and Art History: moments of discipline". Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80018-8.

- Dorfles, Gillo (1969, translated from the 1968 Italian version, Il Kitsch). Kitsch: The World of Bad Taste, Universe Books. LCCN 78-93950

- Elias, Norbert. (1998[1935]) "The Kitsch Style and the Age of Kitsch," in J. Goudsblom and S. Mennell (eds) The Norbert Elias Reader. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Gelfert, Hans-Dieter (2000). "Was ist Kitsch?". Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht in Göttingen. ISBN 3-525-34024-9.

- Giesz, Ludwig (1971). Phänomenologie des Kitsches. 2. vermehrte und verbesserte Auflage München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag. [Partially translated into English in Dorfles (1969)]. Reprint (1994): Ungekürzte Ausgabe. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer Verlag. ISBN 3-596-12034-9 / ISBN 978-3-596-12034-5.

- Gorelik, Boris (2013). Incredible Tretchikoff: Life of an artist and adventurer. Art / Books, London. ISBN 978-1-908970-08-4

- Greenberg, Clement (1978). Art and Culture. Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-6681-8

- Holliday, Ruth and Potts, Tracey (2012) Kitsch! Cultural Politics and Taste, Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6616-0

- Karpfen, Fritz (1925). "Kitsch. Eine Studie über die Entartung der Kunst". Weltbund-Verlag, Hamburg.

- Kristeller, Paul Oskar (1990). "The Modern System of the Arts" (In "Renaissance Thought and the Arts"). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02010-5

- Kulka, Tomas (1996). Kitsch and Art. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01594-2

- Moles, Abraham (nouvelle édition 1977). Psychologie du Kitsch: L'art du Bonheur, Denoël-Gonthier

- Nerdrum, Odd (Editor) (2001). On Kitsch. Distributed Art Publishers. ISBN 82-489-0123-8

- Olalquiaga, Celeste (2002). The Artificial Kingdom: On the Kitsch Experience. University of Minnesota ISBN 0-8166-4117-X

- Reimann, Hans (1936). "Das Buch vom Kitsch". Piper Verlag, München.

- Richter, Gerd, (1972). Kitsch-Lexicon, Bertelsmann. ISBN 3-570-03148-9

- Shiner, Larry (2001). "The Invention of Art". University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-75342-5.

- Thuller, Gabrielle (2006 and 2007). "Kunst und Kitsch. Wie erkenne ich?", ISBN 3-7630-2463-8. "Kitsch. Balsam für Herz und Seele", ISBN 978-3-7630-2493-3. (Both on Belser-Verlag, Stuttgart.)

- Ward, Peter (1994). Kitsch in Sync: A Consumer's Guide to Bad Taste, Plexus Publishing. ISBN 0-85965-152-5

- "Kitsch. Texte und Theorien", (2007). Reclam. ISBN 978-3-15-018476-9. (Includes classic texts of kitsch criticism from authors like Theodor Adorno, Ferdinand Avenarius, Edward Koelwel, Walter Benjamin, Ernst Bloch, Hermann Broch, Richard Egenter, etc.).

External links

- "Kitsch". In John Walker's Glossary of art, architecture & design since 1945.

- Avant-Garde and Kitsch – essay by Clement Greenberg

- Kitsch and the Modern Predicament – essay by Roger Scruton

- Why Dictators Love Kitsch by Eric Gibson, The Wall Street Journal, August 10, 2009