Strawman theory

The strawman theory (also called the strawman illusion) is a pseudolegal conspiracy theory originating in the redemption/A4V movement and prevalent in antigovernment and tax protester movements such as sovereign citizens and freemen on the land. The theory holds that an individual has two personas, one of flesh and blood and the other a separate legal personality (i.e., the "strawman") and that one's legal responsibilities belong to the strawman rather than the physical individual.[1]

Pseudolaw advocates claim that it is possible, through the use of certain "redemption" procedures and documents, to separate oneself from the "strawman", therefore becoming free of the rule of law.[2][3] Hence, the main use of strawman theory is in escaping and denying liabilities and legal responsibility. Tax protesters, "commercial redemption" and "get out of debt free" scams claim that one's debts and taxes are the responsibility of the strawman and not of the real person. They back this claim by misreading the legal definition of person[4] and misunderstanding the distinction between a juridical person[5] and a natural person.[6]

Canadian legal scholar Donald J. Netolitzky has called the strawman theory "the most innovative component of the Pseudolaw Memeplex".[2]

Courts have uniformly rejected arguments relying on the strawman theory,[7][8] which is recognized in law as a scam; the FBI considers anyone promoting it a likely fraudster,[9] and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) considers it a frivolous argument and fines people who claim it on their tax returns.[10][11]

Origin

[edit]The theory appeared circa 1999–2000, when it was conceived by North Dakota farmer turned pseudolegal activist Roger Elvick. A sovereign citizen and tax protester, Elvick was already the primary originator of the redemption movement. The strawman theory overlapped with those of the redemption movement: it eventually became a core concept of sovereign citizen ideology, as it connected their pseudolegal beliefs through an overarching explanation.[2] Around the same period, this set of beliefs was introduced into Canada by Eldon Warman, a student of Elvick's theories who adapted them for a Canadian context. It was further reframed in Canada by the freeman on the land movement, which expanded to other Commonwealth countries.[12]

Assertions

[edit]The theory holds that an individual has two personas. One of them is a physical, tangible human being, and the other is the legal person, often referred to as a legal fiction. When a baby is born in the U.S., a birth certificate is issued, and the parents apply for a Social Security number. Sovereigns say the government uses that birth certificate to set up a secret Treasury account which it funds with an amount ranging from $600,000 to $20 million, depending on the particular sovereign belief system. Hence, every newborn's rights are split between those held by the flesh-and-blood baby and the corporate shell account.[1] One argument used by proponents of the strawman theory is based on a misinterpretation of the term capitis deminutio, used in ancient Roman law for the extinguishment of a person's former legal capacity. Adherents to the theory spell the term "Capitis Diminutio", and claim that capitis diminutio maxima (meaning, in Roman law, the loss of liberty, citizenship, and family) was represented by an individual's name being written in capital letters, hence the idea of individuals having a separate legal personality.[13]

The strawman theory is coupled with the belief that the government is actually a corporation. Said corporation is supposedly bankrupt and uses its citizens as collateral against foreign debt. After each person's strawman is created through their birth certificate, a loan is taken out in the name of the strawman. The proceeds are then deposited into the secret government account associated with the fictitious person’s name.[14]

Proponents of the theory believe the evidence is found on the birth certificate itself. Because many certificates show all capitals to spell out a baby's name, JOHN DOE (under the Strawman theory) is the name of the "straw man", and John Doe is the baby's "real" name. As the child grows, most legal documents will contain capital letters, which means that his state-issued driver's license, his marriage license, his car registration, his criminal court records, his cable TV bill, correspondence from the IRS, etc., pertain to his strawman and not his sovereign identity.[1] In reality, the use of all capital letters is typically done to make certain statements clear and conspicuous, although this is not always the case.[15]

The theory is also based in part on a misinterpretation of the Uniform Commercial Code, which provides an interstate standard for documents such as driver's licenses or for bank accounts: adherents to the theory see this as evidence that these documents, and the associated laws and financial obligations, do not apply to them, but instead to the "straw man".[14]

To distinguish themselves from their "strawman", pseudolaw advocates may refer to their "flesh and blood" identity under by a slightly different name, such as "John of the family Doe" instead of "John Doe".[16] One scheme, notably advocated by sovereign citizen theorist David Wynn Miller, involves adding punctuation—typically hyphens and colons—to one's name: Miller would write his name as :David-Wynn: Miller or David-Wynn: Miller[17] and verbally said it "David hyphen Wynn full colon Miller".[18]

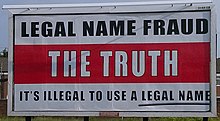

A variation of the strawman theory is found in the "legal name fraud" movement, which believes that birth certificates give the state legal ownership of a personal name and that refusing to use this name removes oneself from the state's authority and a court's jurisdiction.[19][20]

Russell Porisky, a Canadian tax protester who emulated Eldon Warman's ideas,[12] promoted a version of the strawman theory by claiming that people could avoid paying taxes by proclaiming themselves to be "natural persons", in opposition to the government's version of a "person".[21] His concepts relied on a misinterpretation of the definition of a "person" in section 248(1) of the Canadian Income Tax Act, which he combined with the strawman theory.[22] Porisky was convicted in 2012 of tax evasion[23] and was sentenced in 2016 to five and a half years in prison.[24]

Believers of the theory also extend it to law and legal responsibilities, claiming that only their strawman is required to adhere to statutory laws. They also claim that legal proceedings are taken against strawmen rather than persons and when one appears in court they appear as representing their strawman. The justification for this is the false notion that governments cannot force anybody to do anything. A strawman is therefore created which the adherent believes he or she is free to command. Proponents cite a misinterpretation of a passage in chapter 39 of King John's Magna Carta stating in part that, "no freeman will be seized, dispossessed of his property, or harmed except by the law of the land”.[25]

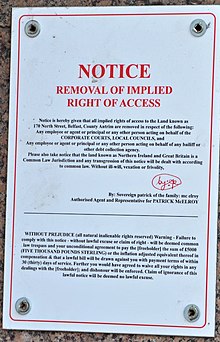

Adherents to the theory believe that separating from their strawman or refusing to be identified as such enables escape from their legal liabilities and responsibilities. This is typically attempted by denying they are a 'person' in the same way as their strawman, or by writing their name in non-standard ways, using red ink, and placing finger prints on court documents. The use of thumbprints and signatures in red ink, in particular, is meant to distinguish "flesh and blood" people from the "strawman", since black and blue inks are believed to indicate corporations.[26] The theory also holds that even after "removing" their strawman, people must remain cautious and take steps to avoid recognizing the validity of government regulations, which would make them succumb to another "invisible contract", experience "joinder" and thus fall back under government authority.[2]

The belief in the strawman articulates with the redemption movement's fraudulent debt and tax payment schemes, which imply that money from the secret account (known in some variations of the theory as a "Cestui Que Vie Trust"[27]) can be used to pay one's taxes, debts and other liabilities by simply writing phrases like "Accepted for Value" or "Taken for Value" on the bills or collection letters, or that the strawman's funds are accessible through the use of certain forms and securities. Such schemes are commonly known as A4V.[7] By attempting to test this aspect of the theory, one may commit various forms of fraud and face criminal charges.[3][28] One purported "redemption" method for appropriating the money from the alleged secret account is to file a UCC-1 financing statement against one's strawman after having taken the steps to "separate" from it.[3]

One Canadian freeman on the land "guru" known under the pseudonym "John Spirit" developed a more sophisticated version of the strawman theory, based on misinterpretations of various international treaties and of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[29][30] His arguments were rejected by Canadian provincial and Federal courts.[12]

Legal status of the theory

[edit]In accepted legal theory there is a difference between what is known as a natural person and that of a corporate person. A corporate personhood applies to business, charities, governments and other recognized organisations. Courts recognize human beings as 'persons', not as a legal fiction joined to a flesh and blood human being but as one and the same.[31] They have never recognized a right to distance oneself from one's person, or the ability to opt out of personhood.[32]

In 2010, Canadian tax protester and vexatious litigant David Kevin Lindsay appealed his 2008 conviction and sentencing on five counts of failing to file income tax returns, on the ground that he was not a "person" as defined by the Income Tax Act. Lindsay's argument was that he had opted out of "personhood" in 1996, which made him "a full liability free will flesh and blood living man". The Supreme Court of British Columbia rejected his claims, commenting that "The ordinary sense of the word 'person' in the (Income Tax Act) is without ambiguity. It is clear that Parliament intended the word in its broadest sense."[33]

In 2012, Associate Justice John D. Rooke of the Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta addressed the strawman theory in detail in his Meads v. Meads decision, concluding:

'Double/split person' schemes have no legal effect. These schemes have no basis in law. There is only one legal identity that attaches to a person. If a person wishes to add a legal 'layer' to themselves, then a corporation is the proper approach.[8]

Judge Norman K. Moon found such tactics an unconvincing argument in 2013 when an individual named Brandon Gravatt tried to overturn a drug conviction and get out of prison. The case was summarily dismissed by the court.[34]

In 2016, a billboard campaign promoted the "legal name fraud" theory in the United Kingdom. Lawyer David Allen Green commented that the theory was "complete tosh" and potentially harmful to litigants who would use it in court: "If people try to use such things to avoid their legal obligations they can end up with county court judgments or even criminal convictions. You may as well walk into court with a t-shirt saying 'I am an idiot'."[35]

In 2021, the District Court of Queensland dismissed an application that relied on the strawman theory, commenting that this argument "may properly be described as nonsense or gobbledygook".[36] The court also pointed out that the strawman scheme, if it had any legal validity, would have adverse consequences for those affected:

An adult human being with full capacity can sue and be sued. They are subject to the criminal laws of this state. These fundamental propositions cannot be doubted. It is true that a natural person can create a legal entity that has a distinct legal personality – such entities are commonly called companies – but this is an adjunct to, rather than a replacement for, the legal personality of the human being. One way of illustrating why this must be so is to consider the consequences of the ability to 'renounce' legal personhood. The law has at times recognised categories of person who did not possess a legal personality. These categories included, before 1833, slaves, who were regarded as chattel property, could be bought and sold, and who had no rights under the law. At times women and children were thought not to possess a legal personality. (...) The fates of people who were in these categories were rarely pleasant. If the applicant were somehow able to renounce his legal personality, he would become a human being without rights. He would be mere property. Such an outcome would be antithetical to our society and system of laws.[37]

Likewise, Donald J. Netolitzky has stressed that :

In modern law, any human being is also innately a legal person, so the historical duality that might serve as a theoretical foundation for "Strawman" Theory is now irrevocably and innately melded together into a single unit. Any human being is a legal person.[29]

It is impossible to dodge the law by insisting that an individual is different from his or her person. If a court can establish a person's identity, regardless of consent or cooperation, the court will engage in proceedings and sanctions against the individual. This is due to the legal principle known as Idem sonans (Latin for "sounding the same") which states that similar sounding names are just as valid in referring to a person.[38] The earliest legal precedent is R v Davis in the United Kingdom in 1851.[39]

If two names spelt differently necessarily sound alike, the court may, as matter of law, pronounce them to be idem sonantia; but if they do not necessarily sound alike, the question whether they are idem sonantia is a question of fact for the jury.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Sovereign Citizens Movement". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d Netolitzky, Donald (2018). "A Rebellion of Furious Paper: Pseudolaw As a Revolutionary Legal System". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3177484. ISSN 1556-5068. SSRN 3177484.

- ^ a b c The Sovereigns: A Dictionary of the Peculiar, Southern Poverty Law Center, August 1, 2010, retrieved 2022-01-20

- ^ "What is Person?". thelawdictionary.org. 4 November 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ "What is Juridical Person?". thelawdictionary.org. 19 October 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ "What is Natural Person?". thelawdictionary.org. 19 October 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ a b Netolitzky, Donald J. (2018). "Organized Pseudolegal Commercial Arguments as Magic and Ceremony". Alberta Law Review: 1045. doi:10.29173/alr2485. ISSN 1925-8356. S2CID 158051933. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ^ a b John D. Rooke (2012-09-18). "Reasons for Decision of the Associate Chief Justice J. D. Rooke". canlii.org. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ "Redemption / Strawman / Bond Fraud". fbi.gov. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ "Internal Revenue Bulletin: 2005-14". irs.gov. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ "26 U.S. Code § 6702 – Frivolous tax submissions". law.cornell.edu. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ a b c Netolitzky, Donald J. (24 May 2018). A Pathogen Astride the Minds of Men: The Epidemiological History of Pseudolaw. Sovereign Citizens in Canada symposium. CEFIR. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3177472. SSRN 3177472. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ Weill, Kelly (4 January 2018). "Republican Lawmaker: Recognize Sovereign Citizens or Pay $10,000 Fine". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ a b Berger, JM (June 2016), Without Prejudice: What Sovereign Citizens Believe (PDF), George Washington University, retrieved 2024-04-01

- ^ "Sovereign Citizens Movement". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 2018-09-12.

- ^ "Nonsense or loophole?", Benchmark, Issue 57, February 2012, pp 18–19

- ^ "Screw the Taxman: The Weird Ideas of Tax Cheaters". DigitalJournal.com. April 24, 2006. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ "The Sovereigns: Leaders of the Movement", Intelligence Report, Southern Poverty Law Center, August 1, 2010, retrieved 2020-06-21

- ^ Dalgleish, Katherine (14 March 2014). "Guns, border guards, and the Magna Carta: the Freemen-on-the-Land are back in Alberta courts". lexology.com. Lexology. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ Kelly, John (June 11, 2016). "The mystery of the 'legal name fraud' billboards". BBC News. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ "B.C. anti-tax crusader sentenced to 5½ years". CBC. August 5, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ^ Netolitzky, Donald J. (2016). "The History of the Organized Pseudolegal Commercial Argument Phenomenon in Canada". Alberta Law Review. 53 (3). Alberta Law Review Society. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ Lindsay, Bethany (January 19, 2012). "Tax-dodging guru convicted on evasion charges". CTV News. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ^ Lindsay, Bethany (March 11, 2021). "As anti-tax guru's fines go unpaid, his bogus ideas are revived in COVID-19 conspiracy circles". CBC. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ^ "Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor". loc.gov. 6 November 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ Williams, Jennifer (9 February 2016). "Why some far-right extremists think red ink can force the government to give them millions". vox.com. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ Sarteschi, Christine M. (May 21, 2023), "Sovereign Citizens and QAnon: The Increasing Overlaps with a Focus on Child Protective Service (CPS) Cases", International Journal of Coercion, Abuse, and Manipulation (IJCAM), retrieved 2023-05-24

- ^ The Sovereign Citizen Movement. Common Documentary Identifiers & Examples (PDF), Anti-Defamation League, 2016, retrieved February 7, 2022

- ^ a b Netolitzky, Donald J.; Warman, Richard (2020). "Enjoy the Silence: Pseudolaw at the Supreme Court of Canada". Alberta Law Review. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ Ha-Redeye, Omar (May 12, 2019), Freemen Arrive at the Ontario Court of Appeal, Slaw.ca, retrieved November 27, 2022

- ^ Meads v. Meads (ABQB 571 (CanLII) 18 September 2012) ("A strange but common OPCA concept is that an individual can somehow exist in two separate but related states. This confusing concept is expressed in many different ways. The ‘physical person’ is one aspect of the duality, the other is a non-corporeal aspect that has many names, such as a “strawman”..."), Text.

- ^ Lovejoy, Hans (7 July 2015). "Taking on the law as a 'strawman'". echo.net. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ "A person is a 'person', B.C. judge rules". CTV news. June 18, 2010. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ United States v. Brandon Gravatt (Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit 26 June 2013) ("Brandon Shane Gravatt appeals the district court's order denying his 18 U.S.C.§3582(c)(2)(2006) motion for sentence reduction. We have reviewed the record and find no reversible error. Accordingly, we affirm the district court's order. United States v. Gravatt, No. 5:01-cr-00736-CMC-1 (D.S.C. March 27, 2013). We dispense with oral argument because the facts and legal contentions are adequately presented in the materials before this court and argument would not aid in the decisional process."), Text.

- ^ Kelly, Jon (11 June 2016). "The mystery of the 'legal name fraud' billboards". BBC News. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ 'Nonsense, gobbledygook': Judge criticises man's bizarre argument to throw out drug charges, news.com.au, September 16, 2021, retrieved November 9, 2022

- ^ "R v Sweet[2021] QDC 216", queenslandjudgments.com.au, September 6, 2021, retrieved 2021-12-27

- ^ "What is IDEM SONANS?". thelawdictionary.org. 9 November 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ John Frederick Archbold; W. N. Welsby (1867). Archbold's Pleading and Evidence in Criminal Cases ... The twelfth edition, including the practice in criminal proceedings generally. Henry Sweet. p. 190.