Motif (music)

Error: no context parameter provided. Use {{other uses}} for "other uses" hatnotes. (help).

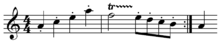

In music, a motif ⓘ or motive is a short musical idea,[5] a salient recurring figure, musical fragment or succession of notes that has some special importance in or is characteristic of a composition: "The motive is the smallest structural unit possessing thematic identity".[3]

The Encyclopédie de la Pléiade regards it as a "melodic, rhythmic, or harmonic cell", whereas the 1958 Encyclopédie Fasquelle maintains that it may contain one or more cells, though it remains the smallest analyzable element or phrase within a subject.[6] It is commonly regarded as the shortest subdivision of a theme or phrase that still maintains its identity as a musical idea. "The smallest structural unit possessing thematic identity".[3] Grove and Larousse[7] also agree that the motif may have harmonic, melodic and/or rhythmic aspects, Grove adding that it "is most often thought of in melodic terms, and it is this aspect of the motif that is connoted by the term 'figure'."

A harmonic motif is a series of chords defined in the abstract, that is, without reference to melody or rhythm. A melodic motif is a melodic formula, established without reference to intervals. A rhythmic motif is the term designating a characteristic rhythmic formula, an abstraction drawn from the rhythmic values of a melody.

A motif thematically associated with a person, place, or idea is called a leitmotif. Occasionally such a motif is a musical cryptogram of the name involved. A head-motif (German: Kopfmotiv) is a musical idea at the opening of a set of movements which serves to unite those movements.

To the self taught Scruton, however, a motif is distinguished from a figure in that a motif is foreground while a figure is background: "A figure resembles a moulding in architecture: it is 'open at both ends', so as to be endlessly repeatable. In hearing a phrase as a figure, rather than a motif, we are at the same time placing it in the background, even if it is...strong and melodious".[1]

Any motif may be used to construct complete melodies, themes and pieces. Musical development uses a distinct musical figure that is subsequently altered, repeated, or sequenced throughout a piece or section of a piece of music, guaranteeing its unity. Such motivic development has its roots in the keyboard sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti and the sonata form of Haydn and Mozart's age. Arguably Beethoven achieved the highest elaboration of this technique; the famous "fate motif" —the pattern of three short notes followed by one long one—that opens his Fifth Symphony and reappears throughout the work in surprising and refreshing permutations is a classic example.

Motivic saturation is the "immersion of a musical motive in a composition", i.e., keeping motifs and themes below the surface or playing with their identity, and has been used by composers including Miriam Gideon, as in "Night is my Sister" (1952) and "Fantasy on a Javanese Motif" (1958), and Donald Erb. The use of motives is discussed in Adolph Weiss' "The Lyceum of Schönberg".[8]

Hugo Riemann defines a motif as, "the concrete content of a rhythmically basic time-unit."[9]

Anton Webern defines a motif as, "the smallest independent particle in a musical idea", which are recognizable through their repetition.[10]

Arnold Schoenberg defines a motif as, "a unit which contains one or more features of interval and rhythm [whose] presence is maintained in constant use throughout a piece".[11]

Head-motif

Head-motif (German: Kopfmotiv) refers to an opening musical idea of a set of movements which serves to unite those movements. It may also be called a motto, and is a frequent device in cyclic masses.[12]

See also

References

- ^ a b Scruton, Roger (1997). The Aesthetics of Music. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-816638-9.

- ^ White, John D. (1976). The Analysis of Music, p.31-34. ISBN 0-13-033233-X.

- ^ a b c d White (1976), p.26-27.

- ^ a b White (1976), p.30.

- ^ New Grove (1980). cited in Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990). Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music (Musicologie générale et sémiologue, 1987). Translated by Carolyn Abbate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691091366/ISBN 0691027145.

- ^ Both cited in Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990). Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music (Musicologie générale et sémiologue, 1987). Translated by Carolyn Abbate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691091366/ISBN 0691027145.

- ^ 1957 Encyclopédie Larousse cited in Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990). Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music (Musicologie générale et sémiologue, 1987). Translated by Carolyn Abbate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691091366/ISBN 0691027145.

- ^ Hisama, Ellie M. (2001). Gendering Musical Modernism: The Music of Ruth Crawford, Marion Bauer, and Miriam Gideon, p.146 and 152. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64030-X.

- ^ Jonas, Oswald (1982). Introduction to the Theory of Heinrich Schenker (1934: Das Wesen des musikalischen Kunstwerks: Eine Einführung in Die Lehre Heinrich Schenkers), p.12. Trans. John Rothgeb. ISBN 0-582-28227-6.

- ^ Webern (1963), p.25-6. Cited in Campbell, Edward (2010). Boulez, Music and Philosophy, p.157. ISBN 978-0-521-86242-4.

- ^ Neff (1999), p.59. Cited in Campbell (2010), p.157.

- ^ Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)