Nepenthes lowii

| Nepenthes lowii | |

|---|---|

| |

| An upper pitcher of Nepenthes lowii from Mount Murud | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Nepenthaceae |

| Genus: | Nepenthes |

| Species: | N. lowii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Nepenthes lowii | |

| Synonyms | |

Nepenthes lowii /nɪˈpɛnθiːz ˈloʊ.i.aɪ/, or Low's pitcher-plant,[4] is a tropical pitcher plant endemic to Borneo. It is named after Hugh Low, who discovered it on Mount Kinabalu. This species is perhaps the most unusual in the genus, being characterised by its strongly constricted upper pitchers, which bear a greatly reduced peristome and a reflexed lid with numerous bristles on its lower surface.[5]

Botanical history

Discovery and naming

Nepenthes lowii was discovered in March 1851 by British colonial administrator and naturalist Hugh Low during his first ascent of Mount Kinabalu. Low wrote the following account of his discovery:[4]

A little way further we came upon a most extraordinary Nepenthes, of, I believe, a hitherto unknown form, the mouth being oval and large, the neck exceedingly contracted so as to appear funnel-shaped, and at right angles to the body of the pitcher, which was large, swollen out laterally, flattened above and sustained in an horizontal position by the strong prolongation of the midrib of the plant as in other species. It is a very strong growing kind and absolutely covered with its interesting pitchers, each of which contains little less than a pint of water and all of them were full to the brim, so admirably were they sustained by the supporting petiole. The plants were generally upwards of 40 ft long, but I could find no young ones nor any flowers, not even traces of either.

The type specimen of N. lowii, designated as Low s.n., was collected by Hugh Low on Mount Kinabalu and is deposited at the herbarium of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (K).[6]

Nepenthes lowii was formally described[note a] in 1859 by Joseph Dalton Hooker.[2] Hooker's original description and illustration were reproduced in Spenser St. John's Life in the Forests of the Far East, published in 1862.[7] St. John wrote the following account of N. lowii on Mount Kinabalu:[7]

We soon came upon the magnificent pitcher-plant, the Nepenthes Lowii, which Mr. Low was anxious to obtain. We could find no young plants, but took cuttings, which the natives said would grow. [...] We at last reached a narrow, rocky ridge, covered with brushwood, but with thousands of plants of the beautiful Nepenthes Lowii growing among them. [...] We sent our men on next morning to wait for us at the cave, while we stayed behind to collect specimens of the Nepenthes Lowii and the Nepenthes Villosa. The former is, in my opinion, the loveliest of them all, and its shape is most elegant. [...] The outside colour of the pitchers is a bright pea-green, the inside dark mahogany; the lid is green, while the glandular are mahogany-coloured. A very elegant claret jug might be made of this shape.

In subsequent years, N. lowii was featured in a number of publications by eminent botanists, such as Friedrich Anton Wilhelm Miquel (1870),[8] Joseph Dalton Hooker (1873),[9] Frederick William Burbidge (1882),[10] Odoardo Beccari (1886),[11] Ernst Wunschmann (1891),[12] Otto Stapf (1894),[13] Harry James Veitch (1897),[14] Jacob Gijsbert Boerlage (1900),[15] and Elmer Drew Merrill (1921).[16] However, most of these publications made only passing mention of N. lowii. The first major taxonomic treatment was that of Günther Beck von Mannagetta und Lerchenau in 1895, who placed N. lowii in its own subgroup (Retiferae) on account of its unusual pitcher morphology.[17]

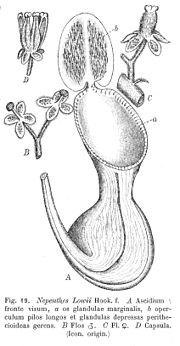

A revised description and illustration of N. lowii were published in John Muirhead Macfarlane's 1908 monograph, "Nepenthaceae".[18] Macfarlane also wrote about N. lowii in the Journal of the Linnean Society in 1914[19] and The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture in 1919.[20]

In 1927, a new illustration of N. lowii was published in an article by Dutch botanist B. H. Danser in the journal De Tropische Natuur.[21] The following year Danser provided a further emended Latin diagnosis[note b] and botanical description of N. lowii in his seminal monograph "The Nepenthaceae of the Netherlands Indies".[22]

New localities

|

|

Nepenthes lowii was discovered on Mount Kinabalu and later found on Bukit Batu Lawi. It was first recorded from Mount Murud by Eric Mjöberg during his first ascent of the mountain in 1922.[23] Mjöberg wrote the following account of the Mount Murud summit area:[23][24]

We found ourselves in a strange landscape where low bushes with thick leathery leaves constituted the predominating vegetation. Here and there smaller trees were seen, among them a conifer with trunk and larger branches practically covered with the yellow blossoms of a small, richly flowering, epiphytic orchid. Bright scarlet or snow-white flowers of rhododendron and similar plants were met with everywhere; and most noticeable were the enormous and characteristically shaped pitchers of Nepenthes lowii, hitherto recorded only from Kinabalu and Batu Lawi.

During the expedition, Mjöberg collected a single specimen of N. lowii from Mount Murud, which has been designated as Mjöberg 115.[24] In 1926, Mjöberg found N. lowii on the north-eastern slope of Bukit Batu Tiban, although he did not collect any specimens.[22]

Another specimen, Beaman 11476, was collected by John H. Beaman between April 10 and April 17, 1995, from the summit ridge of Mount Murud at an elevation of between 2300 and 2400 m above sea level.[24] This latter specimen was collected as part of the eighth botanical expedition to Mount Murud since Eric Mjöberg's first ascent in 1922.[24]

Misidentification

Despite its unique pitcher morphology, N. lowii has been misidentified at least once in the literature; Bertram Evelyn Smythies tentatively assigned a specimen of N. lowii to N. macfarlanei,[6] a species endemic to Peninsular Malaysia, although he suggested it might represent a new species.[25] This misidentification was published in 1965, in the proceedings of the UNESCO Humid Tropics Symposium, which was held in Kuching two years earlier.[3] It was based on a specimen collected by Iris Sheila Darnton Collenette from the Mesilau East River[25] in July 1963.[26] This plant bore several pitchers, each with a well-developed peristome and long bristles on the underside of the lid. The confusion resulted from the fact that the peristome in upper pitchers of N. lowii is usually present only as a series of ridges and that N. macfarlanei also has bristles on the underside of the lid (although they are much shorter than those of N. lowii).[25] Having studied all the Bornean Nepenthes herbarium material held at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Smythies would later confirm that records of N. macfarlanei from the Kinabalu area were erroneous.[27]

Description

Stem and leaves

Nepenthes lowii is a climbing plant. The stem may attain a length of more than 10 m[4] and is up to 20 mm in diameter. Internodes are cylindrical in cross section and up to 8 cm long.[5]

The leaves of this species are coriaceous in texture. The lamina or leaf blade is petiolate, oblong-lanceolate in shape, and up to 30 cm long by 9 cm wide.[25] It has a rounded apex and an abruptly contracted base. The petiole is canaliculate and up to 14 cm long.[25] It forms a flat sheath that clasps the stem for two-thirds to four-fifths of its circumference.[25] Three to four longitudinal veins are present on either side of the midrib. Pinnate veins run straight or obliquely with respect to the lamina. Tendrils are up to 20 cm long and are not usually curled.[5]

Pitchers

The rosette and lower pitchers are bulbous in the lower part and ventricose in the middle, becoming wider towards the mouth. They are smaller than their aerial counterparts, reaching only 10 cm high by 4 cm wide. Lower pitchers are rarely seen, as the plant quickly enters the climbing stage. A pair of fringed wings runs down the front of each pitcher, although these are often reduced and only present in the upper portion of the pitcher cup. The peristome is cylindrical in cross section and widens towards the rear. It is up to 12 mm wide and bears prominent teeth and ribs.[5] The inner portion of the peristome accounts for around 62% of its total cross-sectional surface length.[28] On the inner surface, the glandular region covers the basal half of the pitcher;[5] the waxy zone is reduced.[28] The pitcher lid or operculum is approximately orbiculate in shape. On its underside it possesses a number of very dense fleshy bristles measuring up to 2 cm in length. Other than these distinctive structures, the lid has no appendages. An unbranched spur is inserted near the base of the lid.[5]

The upper pitchers of N. lowii are very distinctive, being globose in the lower part, strongly constricted in the middle, and highly infundibular above. Aerial pitchers are relatively large, growing up to 28 cm high[4] by 10 cm wide. Wings are reduced to ribs in upper pitchers and the peristome is present only as a series of ridges on the edge of the mouth. The inner surface of the pitcher is glandular throughout and has no waxy zone.[29] The vaulted lid is reflexed away from the mouth and is oblong-ovate in shape. It is up to 15 cm long by 9 cm wide[25] and lacks appendages. Numerous bristles, reaching up to 2 cm in length, are present on the lower surface of the lid. As in lower pitchers, the spur is unbranched.[5] The upper pitchers of N. lowii are extremely rigid and almost woody in texture. After drying, the pitchers retain their shape better than those of any other species in the genus.[4]

Inflorescence and indumentum

Nepenthes lowii has a racemose inflorescence. The peduncle reaches 20 cm in length, while the rachis measures up to 25 cm. Partial peduncles are two-flowered, up to 20 mm long, and lack bracts.[25] Sepals are oblong in shape and up to 5 mm long.[5][30] A study of 570 pollen samples taken from three herbarium specimens (J.H.Adam 2406, J.H.Adam 2395 and SAN 23341, collected at an altitude of 1700–2000 m) found the mean pollen diameter to be 33.0 μm (SE = 0.2; CV = 7.8%).[31]

Most parts of the plant are virtually glabrous. However, an indumentum of short brown hairs is present on inflorescences, developing parts, and the edges of rosette leaves.[5]

Ecology

Habitat and distribution

Nepenthes lowii is endemic to a number of isolated peaks in Borneo. In Sabah, it has been recorded from Mount Kinabalu,[5] Mount Tambuyukon,[25] Mount Alab,[32] Mount Mentapok,[4] Mount Monkobo,[5] and Mount Trusmadi.[4] In northern Sarawak, the species is known from Mount Api,[32] Mount Buli,[1] Mount Mulu,[5] Mount Murud,[1] Bukit Batu Lawi,[33] Bukit Batu Tiban,[22] the Hose Mountains,[1] the Tama Abu Range,[1] and Bario.[1] The species has also been recorded from peaks in Brunei, including Bukit Pagon.[4] Nepenthes lowii has an altitudinal distribution of 1650[4] to 2600 m above sea level.[5][34][35][note c]

Nepenthes lowii grows in nutrient-deficient soils[36] of the upper montane zone. The species occurs both terrestrially and as an epiphyte. Its typical habitat is mossy forest or stunted ridge-top vegetation.[5] It often grows in a thick layer of peat moss over ultramafic, sandstone, granite, and limestone substrates.[4]

On Mount Kinabalu, the species has been recorded from the East Ridge, Mesilau East River, and an area below Kambarangoh.[25] Nepenthes lowii used to have a scattered distribution around the Mount Kinabalu summit trail,[37][38][39] occurring in a narrow band between elevations of 1970 and 2270 m above sea level.[4] Many of the N. lowii plants growing along the Kinabalu summit trail died as a result of the El Niño climatic phenomenon of 1997–1998 and others have been destroyed by climbers. It is now difficult to find the species on Mount Kinabalu[40][41] and its presence along the summit trail is "uncertain".[42]

The form of N. lowii from Mount Trusmadi[43] produces significantly larger pitchers than that of nearby Mount Kinabalu.[44] On Mount Murud, N. lowii occurs at elevations above 1860 m. Plants growing near the mountain's summit are very stunted due to the harsher climatic conditions and lack of protecting vegetation.[45]

Mount Mulu is now the easiest place to see N. lowii.[40] On Mount Mulu, the summit vegetation is greatly stunted, rarely exceeding a metre in height. It is dominated by rhododendrons (particularly Rhododendron ericoides),[46] as well as species of the genera Diplycosia and Vaccinium.[47]

Conservation status

The conservation status of N. lowii is listed as Vulnerable on the 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species based on an assessment carried out in 2000.[1] This agrees with the informal classification of the species made by botanist Charles Clarke in 1997, although Clarke noted that it is Conservation Dependent if populations in protected areas are taken into account.[5] However, it differs from the assessment by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre, which classified N. lowii as "rare", placing it between "vulnerable" and "endangered".[48]

Carnivory

Nepenthes lowii is known to catch very few prey items compared to other Nepenthes.[49] Preliminary observations suggest that this particular species may have moved away from a solely (or even primarily) carnivorous nature and be adapted to "catching" the droppings of birds and tree shrews feeding at its nectaries.[5][50][51]

The upper pitchers of N. lowii are unusual in that they have a reflexed lid, which exposes numerous bristles on its underside. A white substance often accumulates amongst these bristles, the identity of which has been the subject of some debate. In the 1960s, J. Harrison assumed that these white beads were snail eggs.[52] E. J. H. Corner, who led the 1961 and 1964 Royal Society Expeditions to Mount Kinabalu, wrote the following:[27][53]

In the early morning there is a ringing gonging which we traced to tupaias (tree-shrews) scampering over the pitchers of N. lowii and banging the old, empty and resonant, pitchers together. The late Professor J. Harrison, of Singapore, discovered that a snail laid its eggs in the hairs under the lid and that the tupaias came to eat them.

However, observations of cultivated N. lowii by Peter D'Amato and Cliff Dodd showed that these white beads were of the plant's own production.[52] The substance has been described as having a sugary taste[5] and "a slightly disagreeable odour".[4] It is unknown why lower pitchers of N. lowii, which are otherwise typical of the genus, also have bristles and produce these white secretions. Charles Clarke suggested that by providing a reward near the ground, the lower pitchers may serve to guide animals towards the upper pitchers.[5]

Clarke carried out a series of field observations relating to N. lowii carnivory. At five of seven sites studied, N. lowii pitchers were found to contain significant amounts of animal excrement.[5] A 2009 study found that mature plants derived 57–100% of their foliar nitrogen from tree shrew droppings.[54][55][56] Another study published the following year showed that the shape and size of the pitcher orifice exactly match the dimensions of a typical tree shrew (Tupaia montana).[57][58] A similar adaptation was found in N. macrophylla and N. rajah, and is also likely to be present in N. ephippiata.[58][59][60][61][62] In all three of these species (N. ephippiata has not been investigated), the colour of the lower lid surface corresponds to T. montana visual sensitivity maxima in the green and blue wavebands, making it stand out against adjacent parts of the pitcher.[63]

Nepenthes lowii is not the first Nepenthes species for which this has been proposed; as early as 1989 it was suggested that N. pervillei, a species from the Seychelles, benefits from bird excrement and may be moving away from carnivory.[64] However, no comprehensive studies have been conducted into the carnivory of N. pervillei and this hypothesis has yet to be tested experimentally.[40][50]

Related species

| N. maxima | N. pilosa | N. clipeata | ||||||

| N. oblanceolata * | N. burbidgeae | N. truncata | ||||||

| N. veitchii | N. rajah | N. fusca | ||||||

| N. ephippiata | N. boschiana | N. stenophylla ** | ||||||

| N. klossii | N. mollis | N. lowii | ||||||

* Now considered a heterotypic synonym of N. maxima.

** Danser's description was based on the type specimen of N. fallax. | ||||||||

In his 1928 monograph, B. H. Danser placed N. lowii in the Regiae clade, together with 14 other species. This differed from the sub-genus classification published by Günther Beck von Mannagetta und Lerchenau in 1895, which placed N. lowii in its own subgroup: Retiferae.[17] Danser explained his assignment of N. lowii to Regiae as follows:[22]

Most aberrant is N. Lowii, the leaves and the stem of which are coarse, whereas the indumentum is almost absent and the pitchers show a peculiar form and have no peristome, the lid is vaulted, the midrib is keeled but has no appendage, the lower surface is covered with thick hairs, the glands of the inner surface of the pitcher are so large, that the interspaces are reduced to lines. All these characters, however seem to have little taxonomic value. The form of the pitcher is analogous to that of N. inermis of the Montanae group, which also has no peristome. The peculiar bristles on the lower surface of the lid are found less developed in N. Macfarlanei. The large, flat glands on the inner surface of the pitchers are also found in the lower part of the pitchers of N. Rajah. This is the reason why I have not distinguished a separate group for this species.

Nepenthes lowii is thought to be most closely related to N. ephippiata.[5] B. H. Danser, who described the latter species in 1928,[22] considered these taxa similar to the point where he could find few reasons to distinguish them in a 1931 article.[65] More recent treatments have retained N. ephippiata as a distinct species and outlined a number of morphological features that distinguish it from N. lowii.[5][34]

The most obvious differences between these species are seen in the upper pitchers; those of N. ephippiata are less constricted in the middle and have a more developed peristome. In addition, N. ephippiata has short tubercles on the underside of the lid, as opposed to the long bristles of N. lowii.[33]

Natural hybrids

At least seven natural hybrids involving N. lowii have been recorded.

N. fusca × N. lowii

This hybrid was initially identified by Charles Clarke as a cross between N. chaniana (known as N. pilosa at the time[66]) and N. lowii.[5][67] However, in their 2008 book, Pitcher Plants of Borneo, Anthea Phillipps, Anthony Lamb and Ch'ien Lee pointed out that the plants exhibit influences of N. fusca, such as a triangular lid and an elongated neck.[68] The authors noted that both N. fusca and N. lowii are common on the summit area of Mount Alab where this plant is found, whereas N. chaniana is rare.[68] Another possible parent species, N. stenophylla, is apparently absent from the site.[68]

This cross was originally discovered by Rob Cantley and Charles Clarke on Bukit Batu Lawi in Sarawak.[5] Clarke later found larger plants of this hybrid in the Crocker Range of Sabah, particularly near the summit of Mount Alab.[5] More recently a single plant has been recorded from Mount Trusmadi.[69] The pitchers of this cross have a slight constriction in the middle and range in colour from green to dark purple throughout.[5]

This hybrid differs from N. fusca in the presence of bristles on the underside of the lid. Conversely, it has a dense indumentum on the stem and at the margins of the lamina, compared to the virtually glabrous stem and leaves of N. lowii. It also differs from N. lowii in having a more developed peristome, which is circular in cross section. While lower pitchers of N. lowii have prominent teeth, those of N. fusca × N. lowii are indistinct. In addition, a glandular appendage is present on the underside of the lid,[5] a trait inherited from N. fusca.

Nepenthes fusca × N. lowii is difficult to confuse with its putative parent species, but is somewhat similar to N. chaniana × N. veitchii. The latter hybrid can be distinguished on the basis of its peristome, which is wider, more flared, and less cylindrical. In addition, this hybrid has a less ovate lid, which lacks the bristles characteristic of N. lowii, and a denser indumentum covering the stem and leaves.[5]

N. lowii × N. macrophylla

Nepenthes lowii × N. macrophylla was discovered on Mount Trusmadi by Johannes Marabini and John Briggs in 1983. Later that year, it was described as N. × trusmadiensis by Marabini.[70] Briggs returned to Mount Trusmadi in 1984, but found only one small group of plants.[4]

Nepenthes × trusmadiensis has petiolate leaves measuring up to 50 cm in length. The pitchers of this hybrid are some of the largest of any Bornean Nepenthes species,[71][72] reaching 35 cm in height. They are roughly intermediate in form between those of its parent species. The lid is held away from the mouth as in N. lowii and bears short bristles on its lower surface.[5] The peristome has prominent ribs and teeth, but is not as developed as that of N. macrophylla.[40] The inflorescence of N. × trusmadiensis may be up to 50 cm long and has two-flowered pedicels.[4] Despite the size of the pitchers, this hybrid is not large in stature.[5]

Nepenthes × trusmadiensis is restricted to the summit ridge of Mount Trusmadi and has been recorded from elevations of 2500 to 2600 m above sea level.[4]

N. lowii × N. stenophylla

In Pitcher-Plants of Borneo, Anthea Phillipps and Anthony Lamb called N. lowii × N. stenophylla the "Mentapok Pitcher-Plant"[4] after Mount Mentapok in Sabah, from which it was collected in 1985 by John Briggs. It has since been recorded from several localities in northern Borneo, including Bukit Pagon in Brunei.[4]

On Mount Mentapok, this hybrid is the result of a cross between a giant form of N. stenophylla with pitchers measuring up to 35 cm and a form of N. lowii with a very dark, almost black, inner surface and a "very narrow, distinctly rough peristome".[4]

Nepenthes lowii × N. stenophylla has petiolate leaves and slender, waisted pitchers up to 25 cm high. The pitcher cup bears long dark streaks similar to those of N. stenophylla, while the striped peristome is flattened and cylindrical in cross section. The lid is ovate in shape and may be held away from the mouth, exposing dark bristles on its lower surface. As in N. lowii, white secretions accumulate between these bristles.[5] The characteristic glandular crest of N. stenophylla is reduced to a small mound under the lid.[4]

Nepenthes lowii × N. stenophylla is only known from mossy forest along summit ridges at elevations of over 1500 m, where the upper altitudinal limit of N. stenophylla overlaps the lower altitudinal limit of N. lowii.[4]

Other hybrids

A number of other natural hybrids involving N. lowii have been reported. These include crosses with N. hurrelliana,[68][73] N. muluensis,[35] N. veitchii,[5] as well as possible hybrids with N. hirsuta[68] and N. tentaculata.[46] A single example of N. lowii × N. rajah grows along the Mesilau nature trail.[42][74]

Notes

Ascidia magna, curva, basi inflata, medio constricta, dein ampliata, infundibuliformia; ore maximo, latissimo, annulo O.

Nepenthes Lowii, H. f.—Caule robusto tereti, foliis crasse coriaceis, longe crasse petiolatis lineari-oblongis, ascidiis magnis curvis basi ventricosis medio valde constrictis, ore maximo ampliato, annulo O, operculo oblongo intus dense longe setoso. (Tab. LXXI.)

Hab.—Kina Balu; alt. 6,000–8,000 feet (Low).

A noble species, with very remarkable pitchers, quite unlike those of any other species. They are curved, 4–10 inches long, swollen at the base, then much constricted, and suddenly dilating to a broad, wide, open mouth, with glossy shelving inner walls, and a minute row of low tubercles round the circumference; they are of a bright pea green, mottled inside with purple. The leaves closely resemble those of Edwardsiana and Boschiana in size, form, and texture, but are more linear-oblong.

I have specimens of what are sent as the male flower and fruit, but not being attached, I have not ventured to describe them as such. The male raceme is eight inches long, dense flowered. Peduncles simple. Perianth with depressed glands on the inner surface, externally rufous and pubescent. Column long and slender. Female inflorescence: a very dense oblong panicle; rachis, peduncles, perianth, and fruit-covered with rusty tomentum. Capsules, two-thirds of an inch long, one-sixth of an inch broad.

Folia mediocria petiolata, lamina lanceolata v. oblonga, nervis longitudinalibus utrinque c. 3, vagina caulis c. 2/3 amplectente ; ascidia rosularum et inferiora ignota ; ascidia superiora magna, parte inferiore globosa, medio valde constricta, os versus infundibuliformia, costis 2 elevatis, ore expanso operculum versus acuto, peristomio 0, operculo oblongo facie inferiore setis crassis longis, prope basin carina crassa obtusa ; inflorescentia racemus longus pedicellis c. 25 mm longis omnibus 2-floris ; indumentum in partibus iuvenilibus parcum tomentosum v. hirsutum, denique subnullum.

- c.^ In a 1992 article, Jumaat Haji Adam, C. C. Wilcock and M. D. Swaine gave an altitudinal range of "about 900 to 3400 m" for N. lowii.[32]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Clarke, C.M.; Cantley, R.; Nerz, J.; Rischer, H.; Witsuba, A. (2000). "Nepenthes lowii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2000. IUCN: e.T39669A10250074. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2000.RLTS.T39669A10250074.en. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ a b c Hooker, J.D. 1859. XXXV. On the origin and development of the pitchers of Nepenthes, with an account of some new Bornean plants of that genus. The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 22(4): 415–424. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1856.tb00113.x

- ^ a b Smythies, B.E. 1965. The distribution and ecology of pitcher-plants (Nepenthes) in Sarawak. UNESCO Humid Tropics Symposium, June–July 1963, Kuching, Sarawak.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Phillipps, A. & A. Lamb 1996. Pitcher-Plants of Borneo. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Kota Kinabalu.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Clarke, C.M. 1997. Nepenthes of Borneo. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Kota Kinabalu.

- ^ a b Schlauer, J. N.d. Nepenthes lowii. Carnivorous Plant Database.

- ^ a b St. John, S. 1862. Life in the Forests of the Far East; or, Travels in northern Borneo. 2 volumes. Smith, Elder & Co., London.

- ^ Miquel, F.A.G. 1870. Nepenthes. Illustrations de la flore l'Archipel Indien 1: 1–48.

- ^ Template:La icon Hooker, J.D. 1873. Ordo CLXXV bis. Nepenthaceæ. In: A. de Candolle Prodromus Systematis Naturalis Regni Vegetabilis 17: 90–105.

- ^ Burbidge, F.W. 1882. Notes on the new Nepenthes. The Gardeners' Chronicle, new series, 17(420): 56.

- ^ Beccari, O. 1886. Rivista delle specie del genere Nepenthes. Malesia 3: 1–15.

- ^ Wunschmann, E. 1891. Nepenthaceae. In: A. Engler & K. Prantl. Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien 3(2): 253–260.

- ^ Stapf, O. 1894. On the flora of Mount Kinabalu, in North Borneo. The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 4: 96–263.

- ^ Veitch, H.J. 1897. Nepenthes. Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society 21(2): 226–255.

- ^ Boerlage, J.G. 1900. Nepenthes. In: Handleiding tot de kennis der flora van Nederlandsch Indië, Volume 3, Part 1. pp. 53–54.

- ^ Merrill, E.D. 1921. A bibliographic enumeration of Bornean plants. Journal of the Straits branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, special number. pp. 281–295.

- ^ a b Template:De icon Beck, G. 1895. Die Gattung Nepenthes. Wiener Illustrirte Garten-Zeitung 20(3–6): 96–107, 141–150, 182–192, 217–229.

- ^ Macfarlane, J.M. 1908. Nepenthaceae. In: A. Engler. Das Pflanzenreich IV, III, Heft 36: 1–91.

- ^ Macfarlane, J.M. 1914. Nepenthaceae. In: L.S. Gibbs. A contribution to the flora and the plant formations of Mount Kinabalu and the Highlands of British North Borneo. Journal of the Linnean Society 42: 125–127.

- ^ Macfarlane, J.M. 1919. Nepenthes. In: L.H. Bailey. The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture, Volume 4. pp. 2122–2130.

- ^ Danser, B.H. 1927. Indische bekerplanten. De Tropische Natuur 16: 197–205.

- ^ a b c d e f g Danser, B.H. 1928. The Nepenthaceae of the Netherlands Indies. Bulletin du Jardin Botanique de Buitenzorg, Série III, 9(3–4): 249–438.

- ^ a b Mjöberg, E. 1925. An Expedition to the Kalabit Country and Mt. Murud, Sarawak. Geographical Review 15(3): 411–427. doi:10.2307/208563

- ^ a b c d Beaman, J.H. 1999. "Preliminary enumeration of the summit flora, Mount Murud, Kelabit Highlands, Sarawak" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) (99.4 KiB) ASEAN Review of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation: 1–23. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kurata, S. 1976. Nepenthes of Mount Kinabalu. Sabah National Parks Publications No. 2, Sabah National Parks Trustees, Kota Kinabalu.

- ^ van Steenis-Kruseman, M.J., et al. 2006. Cyclopaedia of Malesian Collectors: Iris Sheila Darnton Collenette. Nationaal Herbarium Nederland.

- ^ a b Corner, E.J.H. 1996. Pitcher-plants (Nepenthes). In: K.M. Wong & A. Phillipps (eds.) Kinabalu: Summit of Borneo. A Revised and Expanded Edition. The Sabah Society, Kota Kinabalu. pp. 115–121. ISBN 9679994740.

- ^ a b Bauer, U., C.J. Clemente, T. Renner & W. Federle 2012. Form follows function: morphological diversification and alternative trapping strategies in carnivorous Nepenthes pitcher plants. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 25(1): 90–102. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02406.x

- ^ Cheek, M.R. & M.H.P. Jebb 2001. Nepenthaceae. Flora Malesiana 15: 1–164.

- ^ Kaul, R.B. 1982. Floral and fruit morphology of Nepenthes lowii and N. villosa, montane carnivores of Borneo. American Journal of Botany 69(5): 793–803. doi:10.2307/2442970

- ^ Adam, J.H. & C.C. Wilcock 1999. "Palynological study of Bornean Nepenthes (Nepenthaceae)" (PDF). Pertanika Journal of Tropical Agricultural Science 22(1): 1–7.

- ^ a b c Adam, J.H., C.C. Wilcock & M.D. Swaine 1992. "The ecology and distribution of Bornean Nepenthes" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Journal of Tropical Forest Science 5(1): 13–25. - ^ a b Clarke, C.M. & C.C. Lee 2004. Pitcher Plants of Sarawak. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Kota Kinabalu.

- ^ a b Jebb, M.H.P. & M.R. Cheek 1997. A skeletal revision of Nepenthes (Nepenthaceae). Blumea 42(1): 1–106.

- ^ a b McPherson, S.R. 2009. Pitcher Plants of the Old World. 2 volumes. Redfern Natural History Productions, Poole.

- ^ Collins, N.M. 1980. The distribution of soil macrofauna on the west ridge of Gunung (Mount) Mulu, Sarawak. Oecologia 44(2): 263–275. doi:10.1007/BF00572689

- ^ Toyoda, Y. 1972. "Nepenthes and I - Mt. Kinabalu (Borneo, Malaysia) Trip" (PDF). (116 KiB) Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 1(4): 62–63.

- ^ Malouf, P. 1995. "A visit to Kinabalu Park" (PDF). Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 24(3): 64–69.

- ^ Malouf, P. 1995. "A visit to Kinabalu Park" (PDF). Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 24(4): 104–108.

- ^ a b c d Clarke, C.M. 2001. A Guide to the Pitcher Plants of Sabah. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Kota Kinabalu.

- ^ Taylor, D.W. 1982. "Once In a Lifetime" (PDF). Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 11(4): 89–92.

- ^ a b Thong, J. 2006. "Travels around North Borneo – Part 1" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Victorian Carnivorous Plant Society Journal 81: 12–17. - ^ Kitayama, K., J. Kulip, J. Nais & A. Biun 1993. Vegetation Survey on Mount Trus Madi, Borneo a Prospective New Mountain Park. Mountain Research and Development 13(1): 99–105. doi:10.2307/3673647

- ^ Marabini, J. 1984. "A Field Trip to Gunong Trusmadi" (PDF). (442 KiB) Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 13(2): 38–40.

- ^ De Witte, J. 1996. "Nepenthes of Gunung Murud" (PDF). (567 KiB) Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 25(2): 41–45.

- ^ a b Steiner, H. 2002. Borneo: Its Mountains and Lowlands with their Pitcher Plants. Toihaan Publishing Company, Kota Kinabalu.

- ^ Hanbury-Tenison, A.R. & A.C. Jermy 1979. The Rgs Expedition to Gunong Mulu, Sarawak 1977-78. The Geographical Journal 145(2): 175–191. doi:10.2307/634385

- ^ Simpson, R.B. 1995. Nepenthes and Conservation. Curtis's Botanical Magazine 12: 111–118.

- ^ Adam, J.H. 1997. "Prey spectra of Bornean Nepenthes species (Nepenthaceae) in relation to their habitat" (PDF). Pertanika Journal of Tropical Agricultural Science 20(2–3): 121–134.

- ^ a b Clarke, C.M. 2001. Nepenthes of Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Kota Kinabalu.

- ^ Hansen, E. 2001. Where rocks sing, ants swim, and plants eat animals: finding members of the Nepenthes carnivorous plant family in Borneo. Discover 22(10): 60–68.

- ^ a b D'Amato, P. 1998. The Savage Garden: Cultivating Carnivorous Plants. Ten Speed Press, Berkeley.

- ^ Corner, E.J.H. 1978. The plant life. In: M. Luping, C. Wen & E.R. Dingley (eds.) Kinabalu: Summit of Borneo. The Sabah Society, Kota Kinabalu.

- ^ Clarke, C.M., U. Bauer, C.C. Lee, A.A. Tuen, K. Rembold & J.A. Moran 2009. Tree shrew lavatories: a novel nitrogen sequestration strategy in a tropical pitcher plant. Biology Letters 5(5): 632–635. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0311

- ^ Fountain, H. 2009. A Plant That Thrives When Used as a Toilet. The New York Times, June 15, 2009.

- ^ Bryner, J. 2009. Pitcher Plant Doubles as Toilet. LiveScience, June 23, 2009.

- ^ Chin, L., J.A. Moran & C. Clarke 2010. Trap geometry in three giant montane pitcher plant species from Borneo is a function of tree shrew body size. New Phytologist 186 (2): 461–470. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03166.x

- ^ a b Walker, M. 2010. Giant meat-eating plants prefer to eat tree shrew poo. BBC Earth News, March 10, 2010.

- ^ Clarke, C., J.A. Moran & L. Chin 2010. Mutualism between tree shrews and pitcher plants: perspectives and avenues for future research. Plant Signaling & Behavior 5(10): 1187–1189. doi:10.4161/psb.5.10.12807

- ^ Greenwood, M., C. Clarke, C.C. Lee, A. Gunsalam & R.H. Clarke 2011. A unique resource mutualism between the giant Bornean pitcher plant, Nepenthes rajah, and members of a small mammal community. PLoS ONE 6(6): e21114. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021114

- ^ Wells, K., M.B. Lakim, S. Schulz & M. Ayasse 2011. Pitchers of Nepenthes rajah collect faecal droppings from both diurnal and nocturnal small mammals and emit fruity odour. Journal of Tropical Ecology 27(4): 347–353. doi:10.1017/S0266467411000162

- ^ Clarke, C. & J.A. Moran 2011. Incorporating ecological context: a revised protocol for the preservation of Nepenthes pitcher plant specimens (Nepenthaceae). Blumea 56(3): 225–228. doi:10.3767/000651911X605781

- ^ Moran, J.A., C. Clarke, M. Greenwood & L. Chin 2012. Tuning of color contrast signals to visual sensitivity maxima of tree shrews by three Bornean highland Nepenthes species. Plant Signaling & Behavior 7(10): 1267–1270. doi:10.4161/psb.21661

- ^ Juniper, B.E., R.J. Robins & D. Joel 1989. The Carnivorous Plants. Academic Press, London.

- ^ Danser, B.H. 1931. Nepenthaceae. Mitteilungen aus dem Institut für Allgemeine Botanik in Hamburg 3: 217–221.

- ^ Clarke, C.M., C.C. Lee & S. McPherson 2006. Nepenthes chaniana (Nepenthaceae), a new species from north-western Borneo. Sabah Parks Journal 7: 53–66.

- ^ Template:Cs icon Macák, M. 2000. Portréty rostlin - Nepenthes lowii Hook. F.. Trifid 2000(3–4): 51–55. (page 2, page 3, page 4, page 5)

- ^ a b c d e Phillipps, A., A. Lamb & C.C. Lee 2008. Pitcher Plants of Borneo. Second Edition. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Kota Kinabalu.

- ^ Fretwell, S. 2013. Back in Borneo to see giant Nepenthes. Part 3: Mt. Trusmadi and Mt. Alab. Victorian Carnivorous Plant Society Journal 109: 6–15.

- ^ Marabini, J. 1983. Eine neue Nepenthes-Hybride aus Borneo. Mitteilungen der Botanischen Staatssammlung München 19: 449–452.

- ^ Briggs, J.G.R. 1984. The discovery of Nepenthes × trusmadiensis—an impressive new pitcher-plant. Malaysian Naturalist 38(2): 13–15 & 18–19.

- ^ Briggs, J.G.R. 1988. Mountains of Malaysia—a practical guide and manual. Longman, Malaysia.

- ^ Lee, C.C. 2007. Re: lowii and hurrelliana of Mt. Murud Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine. Carnivorous Plants in the tropics.

- ^ A rare find: N. rajah nat. hybrid. Flora Nepenthaceae.

Further reading

- Beaman, J.H. & C. Anderson 2004. The Plants of Mount Kinabalu: 5. Dicotyledon Families Magnoliaceae to Winteraceae. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Kota Kinabalu.

- Bourke, G. 2010. "The climbing pitcher plants of the Kelabit highlands" (PDF). Captive Exotics Newsletter 1(1): 4–7.

- Bourke, G. 2011. The Nepenthes of Mulu National Park. Carniflora Australis 8(1): 20–31.

- Clarke, C. 2013. What Can Tree Shrews Tell Us about the Effects of Climate Change on Pitcher Plants? [video] TESS seminars, 25 September 2013.

- Clarke, C.M., U. Bauer, C.C. Lee, A.A. Tuen, K. Rembold & J.A. Moran 2009. Supplementary methods. Biology Letters, published online on June 10, 2009.

- Damit, A. 2014. A trip to Mount Trus Madi – the Nepenthes wonderland. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 43(1): 19–22.

- Harms, H. 1936. Nepenthaceae. In: A. Engler & K. Prantl. Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, 2 aufl. band 17b.

- Lee, C.C. 2000. Recent Nepenthes Discoveries. [video] The 3rd Conference of the International Carnivorous Plant Society, San Francisco, USA.

- Lee, C.C. 2002. "Nepenthes species of the Hose Mountains in Sarawak, Borneo" (PDF). Proceedings of the 4th International Carnivorous Plant Conference, Hiroshima University, Tokyo: 25–30.

- Template:Id icon Mansur, M. 2001. "Koleksi Nepenthes di Herbarium Bogoriense: prospeknya sebagai tanaman hias" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) In: Prosiding Seminar Hari Cinta Puspa dan Satwa Nasional. Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia, Bogor. pp. 244–253. - McPherson, S.R. & A. Robinson 2012. Field Guide to the Pitcher Plants of Borneo. Redfern Natural History Productions, Poole.

- Meimberg, H., A. Wistuba, P. Dittrich & G. Heubl 2001. Molecular phylogeny of Nepenthaceae based on cladistic analysis of plastid trnK intron sequence data. Plant Biology 3(2): 164–175. doi:10.1055/s-2001-12897

- Template:De icon Meimberg, H. 2002. "Molekular-systematische Untersuchungen an den Familien Nepenthaceae und Ancistrocladaceae sowie verwandter Taxa aus der Unterklasse Caryophyllidae s. l." (PDF). Ph.D. thesis, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich.

- Meimberg, H. & G. Heubl 2006. Introduction of a nuclear marker for phylogenetic analysis of Nepenthaceae. Plant Biology 8(6): 831–840. doi:10.1055/s-2006-924676

- Meimberg, H., S. Thalhammer, A. Brachmann & G. Heubl 2006. Comparative analysis of a translocated copy of the trnK intron in carnivorous family Nepenthaceae. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 39(2): 478–490. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.11.023

- Mey, F.S. 2014. Joined lecture on carnivorous plants of Borneo with Stewart McPherson. Strange Fruits: A Garden's Chronicle, February 21, 2014.

- Template:Jp icon Oikawa, T. 1992. Nepenthes lowii Hook. f.. In: Muyū kusa – Nepenthes (無憂草 – Nepenthes). [The Grief Vanishing.] Parco Co., Japan. pp. 22–25.

- Schwallier, R. 2012. Looking for a toilet on Mount Kinabalu. Expeditions, Scientific American Blog Network, September 21, 2012.

- Thorogood, C. 2010. The Malaysian Nepenthes: Evolutionary and Taxonomic Perspectives. Nova Science Publishers, New York.

- Yeo, J. 1996. A trip to Kinabalu Park. Bulletin of the Australian Carnivorous Plant Society, Inc. 15(4): 4–5.

External links

- Danser, B.H. 1928. 23. Nepenthes Lowii HOOK. F. In: The Nepenthaceae of the Netherlands Indies. Bulletin du Jardin Botanique de Buitenzorg, Série III, 9(3–4): 249–438.