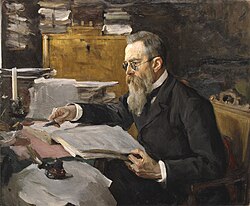

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov (Russian: Николай Андреевич Римский-Корсаков, Nikolaj Andreevič Rimskij-Korsakov), also Nikolay, Nicolai, and Rimsky-Korsakoff, (March 6 (N.S. March 18), 1844 – June 8 (N.S. June 21) 1908) was a Russian composer, one of five Russian composers known as The Five, and was later a teacher of harmony and orchestration. He is particularly noted for a predilection for folk and fairy-tale subjects, and for his extraordinary skill in orchestration, which may have been influenced by his synesthesia.

Biography

Born at Tikhvin, 200 km east of St. Petersburg, into an aristocratic family, Rimsky-Korsakov showed musical ability from an early age, but studied at the Russian Imperial Naval College in St. Petersburg and subsequently joined the Russian Navy. It was only when he met Mily Balakirev in 1861 that he began to concentrate more seriously on music. Balakirev encouraged him to compose and taught him when he was not at sea. (A fictionalized episode of Rimsky-Korsakov's navy service forms the plot of the motion picture Song of Scheherazade (1947), the musical score adapted by Miklós Rózsa.) Through Balakirev he also met the other composers of the group that were to become known as "The Mighty Handful" (better known in English-speaking countries as "The Five"). While in the navy (partly on a world cruise), Rimsky-Korsakov completed his first symphony (1861-1865). This is sometimes claimed to be the first symphony by a Russian, but Anton Rubinstein composed his own first symphony in 1850. Before resigning his commission in 1873, Rimsky-Korsakov also completed the first version of his well known orchestral piece Sadko (1867) and the opera The Maid of Pskov (1872). These three are among several early works which the composer revised later in life.

In 1871, despite being largely group- and self-educated within The Five rather than being conservatory-trained, Rimsky-Korsakov became professor of composition and orchestration at the St Petersburg Conservatory. The next year he married Nadezhda Nikolayevna Purgol'd (1848-1919), who was also a pianist and composer. During his first few years at the Conservatory, Rimsky-Korsakov assiduously studied harmony and counterpoint in order to make up for the lack of such thorough training during his years with The Five.

In 1883 Rimsky-Korsakov worked under Balakirev in the Court Chapel as a deputy. This post gave him the chance to study Russian Orthodox church music. He worked there until 1894. He also became a conductor, leading symphony concerts sponsored by Mitrofan Belyayev (M. P. Belaieff), as well as some programs abroad.

In 1905 Rimsky-Korsakov was removed from his professorship in St Petersburg owing to his expressing some political views of which the authorities disapproved. This sparked a series of resignations by his fellow faculty members, and he was eventually reinstated. The political controversy continued with his opera The Golden Cockerel (Le Coq d'Or) (1906-1907), whose implied criticism of monarchy upset the censors to the point that the premiere was delayed until 1909, after the composer's death.

Towards the end of his life, Rimsky-Korsakov suffered from angina. He died in Lyubensk in 1908, and was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in St. Petersburg. His widow Nadezhda spent the rest of her life preserving the composer's legacy.

The Rimsky-Korsakovs had seven children: Mikhail (b.1873), Sofia (b.1875), Andrey (1878-1940), Vladimir (b.1882), Nadezhda (b.1884), Margarita (1888-1893), and Slavchik (1889-1890). Their daughter Nadezhda married the Russian composer Maximilian Steinberg in 1908. Andrey was a musicologist who wrote a multi-volume study of his father's life and work, which included a chapter devoted to his mother, Nadezhda. A nephew, Georgy Mikhaylovich Rimsky-Korsakov (1901-1965), was also a composer.

Legacy

In his decades at the Conservatory Rimsky-Korsakov taught many composers who would later find fame, including Alexander Glazunov, Sergei Prokofiev, Igor Stravinsky, Ottorino Respighi, and Artur Kapp.

Rimsky-Korsakov's legacy goes far beyond his compositions and his teaching career. His tireless efforts in editing the works of other members of The Five are significant, if controversial. These include the completion of Alexander Borodin's opera Prince Igor (with Alexander Glazunov), orchestration of passages from César Cui's William Ratcliff for the first production in 1869, and the complete orchestration of Alexander Dargomyzhsky's swansong, The Stone Guest. This effort was a practical extension of the fact that Rimsky-Korsakov's early works had been under the intense scrutiny of Balakirev and that the members of The Five during the 1860s and 1870s experienced each other's compositions-in-progress and even collaborated at times.

While the effort for his colleagues is laudable, it is not without its problems for musical reception. In particular, after the death of Modest Mussorgsky in 1881, Rimsky-Korsakov took on the task of revising and completing several of Mussorgsky's pieces for publication and performance. In some cases these versions helped to spread Mussorgsky's works to the West, but Rimsky-Korsakov has been accused of pedantry for "correcting" matters of harmony, etc., in the process. Rimsky-Korsakov's arrangement of Mussorgsky's Night on Bald Mountain is the version generally performed today. However, critical opinion of Mussorgsky has changed over time so that his style, once considered unpolished, is now valued for its originality. This has caused some of Rimsky-Korsakov's other revisions, such as that of Boris Godunov, to fall out of favour and be replaced by productions more faithful to Mussorgsky's original manuscripts.

Although his operas are seldom performed outside of Russia, the music has been widely performed and recorded through the orchestral suites that he compiled from the scores, particularly in the case of Mlada, Tsar Saltan, and Le Coq d'Or. The music of his last opera is remarkably modern for its time and the four-movement suite extracted from its score has enjoyed considerable popularity via concerts and recordings.

His autobiography and his books on harmony and orchestration have been translated into English and published, providing remarkable insights into his life and work.

Rimsky-Korsakov perceived colors associated with major keys as follows [1][2]:

| Tonic note | Color |

|---|---|

| C | white |

| D | yellow |

| E flat | dark bluish-grey |

| E | sparkling sapphire |

| F | green |

| G | rich gold |

| A | rosy colored |

Overview of compositions

Rimsky-Korsakov was a prolific composer. Like his compatriot Cui, his greatest efforts were expended on his operas. There are fifteen operas to his credit, including Kashchey the Immortal and The Tale of Tsar Saltan. The subjects of the operas range from historical melodramas like The Tsar's Bride, to folk operas, such as May Night, to fairytales and legends like Snowmaiden. In their juxtaposed depictions of the real and the fantastic, the operas invoke folk melodies, realistic declamation, lyrical melodies, and artificially constructed harmonies with effective orchestral expression. Most of Rimsky-Korsakov's operas remain in the standard repertoire in Russia to this day. The best known selections from the operas that are known in the West are "Dance of the Tumblers" from Snowmaiden, "Procession of the Nobles" from Mlada, "Song of the Indian Guest" (or, less accurately, "Song of India,") from Sadko, and "Flight of the Bumblebee" from Tsar Saltan, as well as suites from The Golden Cockerel and The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya

Nevertheless, Rimsky-Korsakov's status in the West has long been based on his orchestral compositions, most famous among which are Capriccio espagnol, Russian Easter Festival Overture, and the symphonic suite Scheherazade. In addition, he composed dozens of art songs, arrangements of folk songs, some chamber and piano music, and a considerable number of choral works, both secular and for Russian Orthodox Church service, including settings of portions of the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom (the latter despite the fact that he was a staunch atheist[3][4][5]).

Media

Template:Multi-listen start Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen end

Major literary works

- My Musical Life. [Летопись моей музыкальной жизни -- literally, Chronicle of My Musical Life.] Trans. from the 5th rev. Russian ed. by Judah A. Joffe; ed. with an introduction by Carl Van Vechten. London : Ernst Eulenburg Ltd, 1974.

- Practical Manual of Harmony. [Практический учебник гармонии.] First published, in Russian, in 1885. First English edition published by Carl Fischer in 1930, trans. from the 12th Russian ed. by Joseph Achron. Current English ed. by Nicholas Hopkins, New York, NY: C. Fischer, 2005.

- Principles of Orchestration. [Основы оркестровки.] Begun in 1873 and completed posthumously by Maximilian Steinberg in 1912, first published, in Russian, in 1922 ed. by Maximilian Steinberg. English trans. by Edward Agate; New York: Dover Publications, 1964 ("unabridged and corrected republication of the work first published by Edition russe de musique in 1922").

Bibliographic sources

- Abraham, Gerald. Rimsky-Korsakov: a Short Biography. London: Duckworth, 1945; rpt. New York : AMS Press, 1976. Later ed.: Rimsky-Korsakov. London: Duckworth, 1949.

- Griffiths, Steven. A Critical Study of the Music of Rimsky-Korsakov, 1844-1890. New York: Garland, 1989.

- Rimsky-Korsakov, A.N. Н.А. Римский-Корсаков: жизнь и творчество [N.A. Rimsky-Korsakov: Life and Work]. [5 vols.] Москва: Государственное музыкальное издательство, 1930.

- Richard Taruskin. "The Case for Rimsky-Korsakov," Opera News, vol. 56, nos. 16 and 17 (1991–2), pp. 12–17 and 24-29, respectively.

- Yastrebtsev, Vasily Vasilievich. Reminiscences of Rimsky-Korsakov. Ed. and trans. by Florence Jonas. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985. (Note: this is heavily abridged.)

Other media

References

- ^ *Harrison, John (2001). Synaesthesia: The Strangest Thing, p.123. ISBN 0-19-263245-0.

- ^ Scholes, Percy A., 1970. The Oxford Companion to Music, p. 204.

- ^ Music scholar Gerald Abraham, after going at some length to reconcile Rimsky-Korsakov's lack of religious convictions with the composition of his Christian-themed opera The Invisible City of Kitezh, finally admits, "We know that Rimsky-Korsakov was a religious sceptic." (Abraham, Gerald (1936). "XIII.-- Kitezh". Studies in Russian Music. London: William Reeves / The New Temple Press. pp. p.288.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)) In his article on the composer in The New Grove Russian Masters, Abraham repeats that Rimsky-Korsakov was a non-believer who, nevertheless, could write music on religious themes. "This duality in Rimsky-Korsakov's musical style is matched by strange contradictions in his personality: although cool and objective to an unusual degree, a religious sceptic, he not only delighted in depicting religious ceremonies but was capable of total surrender to the nature-mysticism which possessed him during the composition of Snow Maiden." (Abraham, Gerald (1986). "Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov". The New Grove Russian Masters 2. New York: W.W. Norton and Company. pp. p.27.{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)) - ^ According to Russian-music scholar Simon Morrison, "Beliy apparently planned but did not undertake another novel, called Invisible City (Nevidimiy grad), which was to be based on the ancient Slavonic chronicle about Kitezh. That task was accomplished by another prominent artist of the Silver Age, the composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, who was a positivist, not an idealist, and who feuded with his Symbolist colleagues. Moreover, he was an atheist who complained to his friends that institutionalized religion had become corrupt and hypocritical, since, in his estimation, doctrine promoted exclusion. Rimsky-Korsakov's attitude disturbed Lev Tolstoy, who had abandoned art for religion late in life and encouraged the composer to do the same. On 11 January 1898, the two held a casual debate about religious matters at the writer's home. It concluded in an awkward stalemate, and despite Rimsky-Korsakov's profuse apologies, Tolstoy described the evening caustically as a "face-to-face" encounter with "gloom." Irrespective of the composer's anti-religious outlook, however, in his 1905 opera The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya (Skazaniye o nevidimom grade Kitezhe i deve Fevronii), he explored themes of spiritual conversion and salvation." Simon concludes, "His decision at the end of his career to set a centuries-old tale of spiritual salvation using the music of centuries-old composers attested to his fervent belief that art-- especially musical art-- was in and of itself a kind of miracle."(Morrison, Simon (2002). "2. Rimsky-Korsakov and Religious Syncretism". Russian Opera and the Symbolist Movement. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. p.116-117, 168-169. ISBN 0-520-22943-6.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)) - ^ About the composition of the opera, The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya, The Guardian says, "Belsky originally planned that the new work would be based entirely on the life of Saint Fevroniya of Murom, but Rimsky, a devout atheist - Stravinsky later described him rather disapprovingly as having a mind "closed to any religious or metaphysical idea" - rejected such explicitly Christian subject matter and insisted that the story of Fevroniya be combined with elements of Russian history (the 13th-century invasion by the Mongols) and a strong dose of pantheistic legend, with the whole thing given a strongly nationalistic twist."("The gang of five". The Guardian. February 18, 2005. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help))

External links

- The Rimsky-Korsakov Home Page

- Principles of Orchestration full text with "interactive scores."

- Free scores by Rimsky-Korsakov at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Template:IckingArchive