Operation Junction City

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

| Operation Junction City | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam War | |||||||

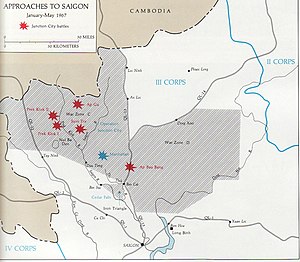

Cedar Falls/Junction City area of operations | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

30,000 men 240 helicopters[5] 700+ combat vehicles: M48 tank, M113 APC | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

U.S: 282 killed 1,500 wounded 3 tanks, 21 AFVs, 5 howitzers, 11 trucks destroyed 54 tanks, 86 AFVs, 6 howitzers, 17 trucks damaged[6] South Vietnam: unknown | U.S reported 2,728 killed[7] | ||||||

Operation Junction City was an 82-day military operation conducted by United States and Republic of Vietnam (RVN or South Vietnam) forces begun on 22 February 1967 during the Vietnam War. It was the largest U.S. airborne operation since Operation Varsity in March 1945, the only major airborne operation of the Vietnam War, and one of the largest U.S. operations of the war.[8] The operation was named after Junction City, Kansas, home of the operation's commanding officer.[9]

The stated aim of the almost three-month engagement involving the equivalent of nearly three U.S. divisions of troops was to locate the elusive 'headquarters' of the Communist uprising in South Vietnam, the COSVN (Central Office of South Vietnam). By some accounts of US analysts at the time, such a headquarters was believed to be almost a "mini-Pentagon," complete with typists, file cabinets, and staff workers possibly guarded by layers of bureaucracy. In truth, after the end of the war, the actual headquarters was revealed by VC archives to be a small and mobile group of people, often sheltering in ad hoc facilities and at one point escaping an errant bombing by some hundreds of meters.

Hammer and Anvil

Junction City's grand tactical plan was a "hammer and anvil" tactic, whereupon airborne forces would "flush out" the VietCong headquarters, sending them to retreat against a prepared "anvil" of pre-positioned forces. Total forces earmarked for this operation included most of the 1st Infantry Division and the 25th Infantry Division including the 27th Infantry Regiment and the 196th Light Infantry Brigade and the airborne troops of the 173rd Airborne Brigade and large armored elements of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment.

American forces of II Field Force, Vietnam started the operation on 22 February 1967 (while Operation Cedar Falls was winding down), the initial operation was carried out by two infantry divisions, the 1st (commanded by Major General William E. DePuy ) and the 25th (Major General Frederick C. Weyand), who led their forces to the north of the operational area to build the "anvil" on which, according to the American plans, the forces of the Viet Cong 9th Division would be crushed. At the same time the movement of infantry (eight battalions with 249 helicopters), took place on the same day including the launch of the paratroopers (the only launch carried out during the entire Vietnam War and the largest since the days of Operation Market Garden in World War II), an airborne regiment of the 173 Airborne Brigade, which went into action west of the deployment of the 1st and the 25th Infantry Divisions.

The operations were apparently at first a success, designated positions were reached without encountering great resistance, and then on February 23, the mechanized forces 11th Armored Cavalry and the 2nd Brigade of the 25th Division, the "hammer" of armor struck against the '"anvil" of the infantry and airborne positioned north and west, giving the communist forces seemingly no chance to escape.

In fact, the Vietcong forces, highly mobile and elusive as ever, and with information sources located deep in the South Vietnamese bureaucracy, had already relocated their headquarters to Cambodia, and launched several attacks to inflict losses and wear down the communists. On February 28 and March 10 there raged two fierce clashes with U.S. forces, the Battle of Prek Klok I and the Battle of Prek Klok II where the US, supported by powerful air strikes and massive artillery support repuled Vietcong attacks, but the strategic outcomes were overall disappointing.

On 18 March 1967, General Bruce Palmer, Jr., new commander of II Field Force, Vietnam, in replacement of General Seaman, launched then the second phase of Junction City, this time directly to the east and carried out again by the mechanized divisions, the 1st Infantry Division and 11th Cavalry, reinforced this time from the 1st Brigade of the 9th Infantry Division (including the 5th Cavalry Regiment). This maneuver gave rise to the toughest battle of the entire operation, the March 19 Battle of Ap Bau Bang II, wherein the 273rd Vietcong Regiment put into difficulties the American armored cavalry although eventually forced to retire by a huge amount of firepower.

In the days after the forces of the Vietcong they launched two more attacks in force, on March 21 and in Ap Gu on April 1, against the 1st and the 25th Infantry Division, both assaults were bloodily repulsed, and the Vietcong 9th Division came out seriously weakened, though still able to fight and, if necessary, to retreat to safety in areas adjacent to the Cambodian border. On April 16 the U.S. command of II Field Force, in agreement with the MACV, decided to continue operations with a third phase of Operation Junction City, until May 14 certain units of the 25th Division Infantry, undertook long and exhausting searches, advancing in the bush, raking villages and retrieving large amounts of materiel, but with little contact with the Communist units, now cautiously moved to a defensive footing.

Outcome

The province of Tay Ninh was picked over thoroughly and Viet Cong forces suffered significant losses, including large amounts of material captured: 810 tonnes of rice, 600 tonnes of small arms, 500,000 pages of documents. The American losses were not negligible, amounting to nearly 300 dead and over 1,500 injured.

According to calculations by the American command the 9th Division VC went seriously weakened by the operations, suffering the loss of 2,728 killed, 34 captured men and 139 deserters. 100 crew-served weapons and 491 individual weapons were captured.[7]

After the operations, the American forces were recalled to other areas of operation and then the country, apparently assured to be in the firm control of the South Vietnamese government fell prey again soon to infiltration by the Viet Cong forces returned from their sanctuaries in Cambodia.

When American troops found in some stores 120 reels of film and logistical equipment for the printing of documents, the command of MACV assumed to have finally found the famous COSVN; however, in reality things were very different. The mobile headquarters, commanded by some mysterious and famous personalities such as generals Thanh, Tran Van Tran Between and Do, had quickly retreated to Cambodia, maintaining its operations and confounding the hopes of the U.S. strategic planners.

With a huge consumption of resources and equipment, including 366,000 rounds of artillery and 3,235 tons of bombs, the American forces had inflicted losses on the communist forces and demonstrated the ability of airborne forces and even mechanized forces (also useful in impervious territory). Despite the tactical results, Junction City on an operational level had missed the most important objectives as well as the failure to yield long term strategic leverage.[4][9]

Notes

- ^ Willbanks, James H. (2013). Vietnam War: The Essential Reference Guide Gale virtual reference library. ABC-CLIO. p. 105. ISBN 9781610691048. Despite the tactical results.. Junction City failed to yield long term strategic leverage

- ^ Hess p. 96

- ^ Turley p 114

- ^ a b Willbanks p. 105

- ^ http://www.pbs.org/battlefieldvietnam/timeline/index2.html

- ^ Lorenz, Maj G.S.; et al. (1983). "Operation Junction City Vietnam Battle Book" (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute. pp. 19–20. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a139612.pdf

- ^ Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ a b Whitney, Catherine (2009). Soldiers Once: My Brother and the Lost Dreams of America's Veterans. Da Capo Press. pp. 53–54.

References

- Summers, Harry G. Historical Atlas of the Vietnam War. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- "Destroying the Haven". TIME. 3 March 1967. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- "Psy-War Success". TIME. 3 March 1967. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- Van, Dinh Thi, "I Engaged in Intelligence Work" The Gioi Publishers, Hanoi, 2006.

- "The Lure of the Lonely Patrol: Forcing the Enemy to Fight". TIME. 14 April 1967. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

Further reading

- Hess, Gary R. (1998). Vietnam and the United States: Origins and Legacy of War: Volume 7 of Twayne's international history series. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 9780805716764.

- Jaques, Tony (2006). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8500 Battles from Antiquity Through the Twenty-first Century. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313335365.

- Rogers, Lieutenant General Bernard William (1989). Cedar Falls – Junction City: A Turning Point. Vietnam Studies. United States Army Center of Military History.

- Turley, William S. (2008). The Second Indochina War: A Concise Political and Military History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 114. ISBN 9780742557451.

External links

- Article about original 173rd jungle jacket worn by Junction City vet

- Battlefield:Timeline, PBS

- After Action Report (Logistical)

- 1/4 Cavalvry After Action Report – JUNCTION CITY II – 26 Apr 67