Oxalate

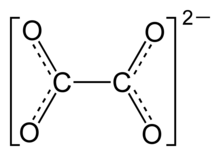

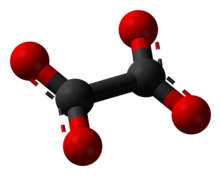

Oxalate (IUPAC: ethanedioate) is the dianion with the formula C2O42−, also written (COO)22−. Either name is often used for derivatives, such as salts of oxalic acid (for example sodium oxalate, ((Na+)2C2O42−) or esters thereof (for example dimethyl oxalate, ((CH3)2C2O4). Oxalate also forms coordination compounds where it is sometimes abbreviated as ox.

Many metal ions form insoluble precipitates with oxalate, a prominent example being calcium oxalate, the primary constituent of the most common kind of kidney stones.

Relationship to oxalic acid

The dissociation of protons from oxalic acid proceeds in a stepwise manner as for other polyprotic acids. Loss of a single proton results in the monovalent hydrogenoxalate anion HC2O4−. A salt with this anion is sometimes called an acid oxalate, monobasic oxalate, or hydrogen oxalate. The equilibrium constant (Ka) for loss of the first proton is 5.37×10−2 (pKa = 1.27). The loss of the second proton, which yields the oxalate ion has an equilibrium constant of 5.25×10−5 (pKa = 4.28). These values imply that, in solutions with neutral pH, there is no oxalic acid, and only trace amounts of hydrogen oxalate.[1] The literature is often unclear on the distinction between H2C2O4, HC2O4-, and C2O42-, and the collection of species is referred to oxalic acid.

Structure

X-ray crystallography of simple oxalate salts show that the oxalate anion may adopt either a planar conformation with D2h molecular symmetry, or a conformation where the O-C-C-O dihedrals approach 90° with approximate D2d symmetry.[2] Specifically, the oxalate moiety adopts the planar, D2h conformation in the solid-state structures of M2C2O4 (M = Li, Na, K).[3] However, in structure of Cs2C2O4 the O-C-C-O dihedral angle is 81(1)°.[4][5] Therefore, Cs2C2O4 is more closely approximated by a D2d symmetry structure because the two CO2 planes are staggered. Interestingly, two forms of Rb2C2O4 have been structurally characterized by single-crystal, X-ray diffraction: one contains a planar and the other a staggered oxalate.

As the preceding examples indicate that the conformation adopted by the oxalate dianion is dependent upon the size of the alkali metal to which it is bound, some have explored the barrier to rotation about the central C−C bond. It was determined computationally that barrier to rotation about this bond is roughly 2–6 kcal/mole for the free dianion, C2O42−.[6] Such results are consistent with the interpretation that the central carbon-carbon bond is best regarded as a single bond with only minimal pi interactions between the two CO2 units.[2] This barrier to rotation about the C−C bond (which formally corresponds to the difference in energy between the planar and staggered forms) may be attributed to electrostatic interactions as unfavorable O−O repulsion is maximized in the planar form.

It is important to note that oxalate is often encountered as a bidentate, chelating ligand, such as in Potassium ferrioxalate. When the oxalate chelates to a single metal center, it always adopts the planar conformation.

Occurrence in nature

Oxalate occurs in many plants, where it is synthesized via the incomplete oxidation of carbohydrates.

Oxalate-rich plants include fat hen ("lamb's quarters"), sorrel, and several Oxalis species. The root and/or leaves of rhubarb and buckwheat are high in oxalic acid.[7] Other edible plants that contain significant concentrations of oxalate include—in decreasing order—star fruit (carambola), black pepper, parsley, poppy seed, amaranth, spinach, chard, beets, cocoa, chocolate, most nuts, most berries, fishtail palms, New Zealand spinach (Tetragonia tetragonioides) and beans.[citation needed] Leaves of the tea plant (Camellia sinensis) contain among the greatest measured concentrations of oxalic acid relative to other plants. However the beverage derived by infusion in hot water typically contains only low to moderate amounts of oxalic acid per serving due to the small mass of leaves used for brewing.

| Common high-oxalate foods[8] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Food Item | Serving |

Oxalate Content (mg) |

| Beet greens, cooked | 1/2 cup | 916 |

| Purslane, leaves, cooked | 1/2 cup | 910 |

| Rhubarb, stewed, no sugar | 1/2 cup | 860 |

| Spinach, cooked | 1/2 cup | 750 |

| Beet, cooked | 1/2 cup | 675 |

| Chard, Swiss, leaves cooked | 1/2 cup | 660 |

| Rhubarb, canned | 1/2 cup | 600 |

| Spinach, frozen | 1/2 cup | 600 |

| Beet, pickled | 1/2 cup | 500 |

| Poke Greens, cooked | 1/2 cup | 476 |

| Endive, raw | 20 long leaves | 273 |

| Cocoa, dry | 1/3 cup | 254 |

| Dandelion greens, cooked | 1/2 cup | 246 |

| Okra, cooked | 8 - 9 pods | 146 |

| Sweet potato, cooked | 1/2 cup | 141 |

| Kale, cooked | 1/2 cup | 125 |

| Peanuts, raw | 1/3 cup (1-3/4 oz) | 113 |

| Turnip greens, cooked | 1/2 cup | 110 |

| Chocolate, unsweetened | 1 oz. | 91 |

| Parsnips, diced, cooked | 1/2 cup | 81 |

| Collard greens, cooked | 1/2 cup | 74 |

| Pecans, halves, raw | 1/3 cup (1-1/4 oz) | 74 |

| Tea, leaves (4 min. infusion) | 1 level tsp in 7 oz water | 72 |

| Cereal germ, toasted | 1/4 cup | 67 |

| Gooseberries | 1/2 cup | 66 |

| Potato, Idaho white, baked | 1 medium | 64 |

| Carrots, cooked | 1/2 cup | 45 |

| Apple, raw with skin | 1 medium | 41 |

| Brussels sprouts, cooked | 6 - 8 medium | 37 |

| Strawberries, raw | 1/2 cup | 35 |

| Celery, raw | 2 stalks | 34 |

| Milk chocolate bar | 1 bar (1.02 oz) | 34 |

| Raspberries, black, raw | 1/2 cup | 33 |

| Orange, edible portion | 1 medium | 24 |

| Green beans, cooked | 1/2 cup | 23 |

| Chives, raw, chopped | 1 tablespoon | 19 |

| Leeks, raw | 1/2 medium | 15 |

| Blackberries, raw | 1/2 cup | 13 |

| Concord grapes | 1/2 cup | 13 |

| Blueberries, raw | 1/2 cup | 11 |

| Currants, red | 1/2 cup | 11 |

| Apricots, raw | 2 medium | 10 |

| Raspberries, red, raw | 1/2 cup | 10 |

| Broccoli, cooked | 1 large stalk | 6 |

| Cranberry juice | 1/2 cup (4 oz) | 6 |

The "gritty mouth" feeling one experiences when drinking milk with a rhubarb dessert is caused by precipitation of calcium, abstracted from the casein in dairy products, as calcium oxalate.[citation needed]

Physiological effects

In the body, oxalic acid combines with divalent metallic cations such as calcium (Ca2+) and iron(II) (Fe2+) to form crystals of the corresponding oxalates which are then excreted in urine as minute crystals. These oxalates can form larger kidney stones that can obstruct the kidney tubules. An estimated 80% of kidney stones are formed from calcium oxalate.[9] Those with kidney disorders, gout, rheumatoid arthritis, or certain forms of chronic vulvar pain (vulvodynia) are typically advised to avoid foods high in oxalic acid. Methods to reduce the oxalate content in food are of current interest.[10]

Magnesium (Mg2+) oxalate is 567 times more soluble than calcium oxalate, so the latter is more likely to precipitate out when magnesium levels are low and calcium and oxalate levels are high.

Magnesium oxalate is a million times more soluble than mercury oxalate. Oxalate solubility for other metals decreases in the order Ca > Cd > Zn > {Mn,Ni,Fe,Cu} > {As,Sb,Pb} > Hg. The highly insoluble iron(II) oxalate appears to play a major role in gout, in the nucleation and growth of the otherwise extremely soluble sodium urate. This explains why gout usually appears after age 40, when ferritin levels in blood exceed 100 ng/dl. Beer is rich in oxalate and iron, and ethanol increases iron absorption and magnesium elimination, so beer intake greatly increases the risk of a gout attack.

Cadmium catalyzes the transformation of vitamin C into oxalic acid. This can be a problem for people exposed to high levels of cadmium in the diet, in the workplace, or through smoking.

In studies with rats, calcium supplements given along with foods high in oxalic acid can cause calcium oxalate to precipitate out in the gut and reduce the levels of oxalate absorbed by the body (by 97% in some cases.)[11][12]

Oxalic acid can also be produced by the metabolism of ethylene glycol ("antifreeze"), glyoxylic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C).[13][dubious ]

Powdered oxalate is used as a pesticide in beekeeping to combat the bee mite.

Some fungi of the genus Aspergillus produce oxalic acid, which reacts with calcium from the blood or tissue to precipitate calcium oxalate.[14]

There is some preliminary evidence that the administration of probiotics can affect oxalic acid excretion rates[15] (and presumably oxalic acid levels as well.)

As a ligand

Oxalate, the conjugate base of oxalic acid, is an excellent ligand for metal ions. It usually binds as a bidentate ligand forming a 5-membered MO2C2 ring. An illustrative complex is potassium ferrioxalate, K3[Fe(C2O4)3]. The drug Oxaliplatin exhibits improved water solubility relative to older platinum-based drugs, avoiding the dose-limiting side-effect of nephrotoxicity. Oxalic acid and oxalates can be oxidized by permanganate in an autocatalytic reaction. One of the main applications of oxalic acid is a rust-removal, which arises because oxalate forms water soluble derivatives with the ferric ion.

Safety

Although unusual, consumption of oxalates (for example, the grazing of animals on oxalate-containing plants such as greasewood[disambiguation needed] or Bassia hyssopifolia, or human consumption of sorrel) may result in kidney disease or even death due to oxalate poisoning. The presence of Oxalobacter formigenes in the gut flora can prevent this. Cadmium catalyzes the transformation of vitamin C into oxalic acid and can result from smoking heavily, ingesting produce tainted with Cd or from industrial exposure to Cd.

See also

Raphides

Oxalate salts

- sodium oxalate - Na2C2O4

- calcium oxalate - CaC2O4, a major component of kidney stones

Oxalate complexes

- potassium ferrioxalate - K3[Fe(C2O4)3], an iron complex with oxalate ligands

Oxalate esters

- diphenyl oxalate - (C6H5)2C2O4

- dimethyl oxalate - (CH3)2C2O4

References

- ^ Wilhelm Riemenschneider, Minoru Tanifuji "Oxalic Acid" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2002, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a18_247.

- ^ a b The Oxalate Dianion, C2O42–: Planar or Nonplanar? Philip A. W. Dean Journal of Chemical Education 2012 89 (3), 417-418 doi:10.1021/ed200202r

- ^ Reed, D. A.; Olmstead, M. M. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 1981, 37, 938−939.; Beagley, B.; Small, R. W. H. Acta Crystallogr. 1964, 17, 783−788.

- ^ In the figure 81(1)°, the (1) indicates that 1° is the standard uncertainty of the measured angle of 81°

- ^ Dinnebier, R. E.; Vensky, S.; Panthöfer, M.; Jansen, M. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 1499−1507.

- ^ Clark, T.; Schleyer, P. v. R. J. Comput. Chem. 1981, 2, 20−29.; Dewar, M. J. S.; Zheng, Y.-J. J. Mol. Struct. (THEOCHEM) 1990, 209, 157−162.; Herbert, J. M.; Ortiz, J. V. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 11786−11795.

- ^ Streitweiser, Andrew Jr.; Heathcock, Clayton H.: Introduction to Organic Chemistry, Macmillan 1976, p 737

- ^ Resnick, Martin I. (1990). Urolithiasis, A Medical and Surgical Reference. W.B. Saunders Company. p. 158. ISBN 0-7216-2439-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Coe FL, Evan A, Worcester E. (2005). "Kidney stone disease". J Clin Invest. 115 (10): 2598–608. doi:10.1172/JCI26662. PMC 1236703. PMID 16200192.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Betsche, T.; Fretzdorff, B. (2005). "Biodegradation of oxalic acid from spinach using cereal radicles". J Agric Food Chem. 53 (25): 9751–8. doi:10.1021/jf051091s. PMID 16332126.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morozumi M, Hossain RZ, Yamakawa KI, Hokama S, Nishijima S, Oshiro Y, Uchida A, Sugaya K, Ogawa Y (2006). "Gastrointestinal oxalic acid absorption in calcium-treated rats". Urol Res. 34 (3): 168. doi:10.1007/s00240-006-0035-7. PMID 16444511.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hossain RZ, Ogawa Y, Morozumi M, Hokama S, Sugaya K (2003). "Milk and calcium prevent gastrointestinal absorption and urinary excretion of oxalate in rats". Front Biosci. 8 (1–3): a117–25. doi:10.2741/1083. PMID 12700095.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mandl J, Szarka A, Bánhegyi G (2009). "Vitamin C: update on physiology and pharmacology". British Journal of Pharmacology. 157 (7): 1097–1110. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00282.x. PMC 2743829. PMID 19508394.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pabuccuoglu U. (2005). "Aspects of oxalosis associated with aspergillosis in pathology specimens". Pathol Res Pract. 201 (5): 363–8. doi:10.1016/j.prp.2005.03.005. PMID 16047945.

- ^ Lieske JC, Goldfarb DS, De Simone C, Regnier C. (2005). "Use of a probiotic to decrease enteric hyperoxaluria". Kidney Int. 68 (3): 1244–9. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00520.x. PMID 16105057.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)