Palace Theatre, London

Royal English Opera House Palace Theatre of Varieties | |

Palace Theatre | |

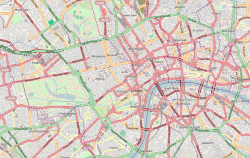

| Address | Shaftesbury Avenue London, W1 United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°30′47″N 0°07′46″W / 51.513167°N 0.129472°W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | Nimax Theatres |

| Designation | Grade II* |

| Type | West End theatre |

| Capacity | 1,400 (4 levels) |

| Production | Harry Potter and the Cursed Child |

| Construction | |

| Opened | January 1891 |

| Rebuilt | 1892 (conversion by Walter Emden) |

| Architect | Thomas Edward Collcutt |

| Website | |

| Palace Theatre official website | |

The Palace Theatre is a West End theatre in the City of Westminster in London. Its red-brick facade dominates the west side of Cambridge Circus behind a small plaza near the intersection of Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road. The Palace Theatre seats 1,400.

Richard D'Oyly Carte, producer of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, commissioned the theatre in the late 1880s. It was designed by Thomas Edward Collcutt and intended to be a home of English grand opera. The theatre opened as the "Royal English Opera House" in January 1891 with a lavish production of Arthur Sullivan's opera Ivanhoe. Although this ran for 160 performances, followed briefly by André Messager's La Basoche, Carte had no other works ready to fill the theatre. He leased it to Sarah Bernhardt for a season and sold the opera house within a year at a loss. It was then converted into a grand music hall and renamed the Palace Theatre of Varieties, managed successfully by Charles Morton. In 1897, the theatre began to screen films as part of its programme of entertainment. In 1904, Alfred Butt became manager and continued to combine variety entertainment, including dancing girls, with films. Herman Finck was musical director at the theatre from 1900 until 1920. The Marx Brothers appeared at the theatre in 1922, performing selections from their Broadway shows.

In 1925, the musical comedy No, No, Nanette opened at the Palace Theatre, followed by other musicals, for which the theatre became known. The Sound of Music ran for 2,385 performances at the theatre, opening in 1961. Jesus Christ Superstar ran from 1972 to 1980, and Les Misérables played at the theatre for nineteen years, beginning in 1985. In 1983, Andrew Lloyd Webber purchased and by 1991 had refurbished the theatre. Monty Python's Spamalot played at the theatre from 2006 until January 2009, and Priscilla Queen of the Desert opened at the Palace in March 2009 and closed in December 2011. Between February 2012 and June 2013, it hosted a production of Singin' in the Rain.

In June 2016, the play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child opened at the theatre.[1]

History

Early years

Commissioned by impresario Richard D'Oyly Carte in the late 1880s, it was designed by Thomas Edward Collcutt. Carte intended it to be the home of English grand opera, much as his Savoy Theatre had been built as a home for English light opera, beginning with the Gilbert and Sullivan series. The foundation stone, laid by his wife Helen in 1888, can still be seen on the façade of the theatre, almost at ground level to the right of the entrance. The theatre's design was considered to be novel. The upper levels are supported by heavy steel cantilevers built into the back walls, removing the need for supporting pillars that impede the view of the stage. The tiers, corridors, staircases, landings are all constructed of concrete to reduce the risk and damage that might be done by fire.[2]

The theatre opened as the "Royal English Opera House" in January 1891 with Arthur Sullivan's Ivanhoe. No expense was spared to make the production a success, including a double cast and "every imaginable effect of scenic splendour".[3] It ran for 160 performances, but when Ivanhoe finally closed in July, Carte had no new work to replace it, and the opera house had to close. One opera is not enough to sustain an opera house venture. It was, as critic Herman Klein observed, "the strangest comingling of success and failure ever chronicled in the history of British lyric enterprise!"[4] Sir Henry Wood, who had been répétiteur for the production, recalled in his autobiography that "[if] Carte had had a repertory of six operas instead of only one, I believe he would have established English opera in London for all time. Towards the end of the run of Ivanhoe I was already preparing the Flying Dutchman with Eugène Oudin in the name part. He would have been superb. However, plans were altered and the Dutchman was shelved."[5]

The theatre re-opened in November 1891, with André Messager's La Basoche (with David Bispham in his first London stage performance) at first alternating in repertory with Ivanhoe, and then La Basoche alone, closing in January 1892. Carte had no other works ready, and so he leased the theatre to Sarah Bernhardt for a season and sold the opera house within a year at a loss. It was then converted by Walter Emden into a grand music hall and renamed the Palace Theatre of Varieties, managed by Charles Morton, known as the 'Father of Music Halls', who made it into a successful enterprise.[6] Denied permission by the London County Council to construct the promenade, which was such a popular feature of adult entertainment at the Empire and Alhambra theatres, the Palace compensated by featuring apparently nude women in tableaux vivants, though the concerned LCC hastened to reassure patrons that the girls who featured in these displays were actually wearing flesh toned body stockings and were not naked.[7]

In March 1897, the theatre began to screen films from the American Biograph Company as part of its programme of entertainment, these films pioneered the 70 mm format which helped give an exceptionally large and clear image filling the proscenium arch. The performances included early newsreels from around the world, many of them made by film pioneer William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, including film of the Anglo-Boer War (1900). The Palace continued to show films as part of its variety and musical programmes.[8]

20th century

In 1904, Morton was succeeded by manager Alfred Butt,whose father Alfred Beyfus and associates had purchased the theatre.[9] Butt introduced many innovations to the theatre, including dancers, such as Maud Allan (including her famous Salomé)[10] and Anna Pavlova, and elegant pianist-singer Margaret Cooper.[11] Oliver G Pike premièred his first film, In Birdland, at the theatre in August 1907. This was the first British wildlife film to be screened to a paying audience.[12] On 26 February 1909, the general public first saw Kinemacolor in a programme of 21 short films shown at the Theatre.[13]

The name of the theatre was finally changed to The Palace Theatre in 1911. Herman Finck was musical director at the theatre from 1900 until 1920,[14] with whose orchestra he made many recordings. The theatre was famous not only for its orchestra, but also for the beautiful Palace Girls, for whom Finck composed many dances. In 1911, the Palace Girls performed a song and dance number, which was originally called Tonight but became very popular as a romantic instrumental piece In The Shadows. In 1912, the theatre hosted the first Royal Variety Performance in Britain, commanded by King George V, and produced by Butt.[15] During the First World War, the theatre presented revues, and Maurice Chevalier became known to British audiences. After the war, the theatre was used mostly for films for a few years,[16] but the Marx Brothers appeared at the theatre in 1922, performing selections from their Broadway shows.[17]

On 11 March 1925, the musical comedy No, No, Nanette opened at the Palace Theatre starring Binnie Hale and George Grossmith, Jr. The run of 665 performances made it the third longest-running West End musical of the 1920s. Princess Charming ran for 362 performances beginning in 1926. The Palace Theatre was also the venue for Rodgers and Hart's The Girl Friend (1927) and Fred Astaire's final stage musical Gay Divorce (1933). In 1939–1940, Cicely Courtneidge and Jack Hulbert appeared at the theatre in Under Your Hat, a spy story co-written by Hulbert, with music and lyrics by Vivian Ellis.[18] Later musical theatre works that played with success at the theatre included Song of Norway, King's Rhapsody, Anything Goes, Flower Drum Song and Where's Charley?, among others.[16][19] The Entertainer, starring Laurence Olivier, transferred to the theatre from the Royal Court Theatre in 1957.[20] In the 1960s, The Sound of Music ran for 2,385 performances, from 1961, and Cabaret followed in 1968.[19] The Danny La Rue revue Danny at the Palace played for two years from 1970.[16]

Two more exceptional runs took place at The Palace during the last decades of the 20th century: Jesus Christ Superstar (3,358 performances from 1972 to 1980) and Les Misérables, which played at the theatre for nineteen years after moving from the Barbican Centre on 4 December 1985. The production moved to the Queen's Theatre on April 2004 to continue its record-setting run. In between, Song and Dance played from 1982 to 1984. In 1983, Andrew Lloyd Webber purchased the theatre for £1.3 million and began a series of renovations to the auditorium, including uncovering the famous marble and onyx panels lurking below a layer of paint. He restored the theatre's facade, later commenting: "I removed the huge neon sign that defaced the glorious terracotta exterior, much to the chagrin of West End producers who told me I had removed the greatest theatre advertising sight in London."[21]

21st century

After Les Misérables left the theatre in 2004, Lloyd Webber refurbished and restored the auditorium and front of the house, removing the paint that covered the Italian marble.[21] Lloyd Webber premiered his musical The Woman in White at the Palace later in 2004, which ran for 19 months. Monty Python's Spamalot opened in 2006 and ran until 2009. It was replaced by Priscilla Queen of the Desert, which played through 2011, and Singin' In The Rain played from 2012[22] to 2013, followed by The Commitments from 2013 to 2015.[23]

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, a two-part play written by Jack Thorne based on an original story by Thorne, J. K. Rowling and John Tiffany,[24] began previews at the theatre on 7 June 2016,[25] Both parts opened officially on 30 July.[26] Advance sales have been strong.[27][28]

The theatre was Grade II* listed by English Heritage in June 1960.[29] It is one of the 40 theatres featured in the 2012 DVD documentary series Great West End Theatres, presented by Donald Sinden.[30] In April 2012, Lloyd Webber's Really Useful Group sold the building to Nimax Theatres (Nica Burns and Max Weitzenhoffer). Nimax purchased the Apollo, Duchess, Garrick and Lyric Theatres from Really Useful in 2005.[21]

Recent notable productions

- The Commitments (August 2013 – November 2015)

- Harry Potter and the Cursed Child (July 2016 – )

In popular culture

In the 1977 Doctor Who serial The Talons of Weng-Chiang, the villain Li H'sen Chang masquerades as magician and ventriloquist performing at the Palace Theatre when the Doctor brings Leela there to discover the customs of her Victorian ancestors.[31] In the 2004 novel Full Dark House, by Christopher Fowler, a series of gruesome murders take place in the Palace during the London Blitz amid a production of Orpheus in the Underworld.[32]

References

- ^ "How to get tickets to Harry Potter and the Cursed Child". whatsonstage.com. 23 October 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ Arthurlloyd.co.uk feature on the theatre, p. 5, accessed 18 October 2011

- ^ "Hesketh Pearson, Gilbert and Sullivan

- ^ Hermann Klein's 1903 description of Ivanhoe, Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 3 October 2003, accessed 12 April 2012

- ^ Henry J. Wood (1938). My Life of Music. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd.

- ^ Pages about Morton's management in feature on the theatre, p. 2, ArthurLloyd.co.uk, accessed 18 October 2011

- ^ Gavin Weightman. Bright Lights, Big City: London Entertained, 1830–1950. Collins & Brown. pp. 94–95.

- ^ "Features: Victorian 'Cinemas'". British Film Institute. 1996. Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- ^ Smith, Graeme. The Theatre Royal: Entertaining a Nation (2008)

- ^ Butt's management in feature on the theatre, ArthurLloyd.co.uk, accessed 18 October 2011

- ^ Palace Theatre, ArthurLloyd.co.uk, accessed 18 October 2011

- ^ "In Birdland (1907)". WildFilmHistory. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ David Fisher (2 November 2009). "1909 Film history timetable". Chronomedia. Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- ^ Palace Theatre Feature

- ^ Page about the Royal Command Performance

- ^ a b c Ellacott, Vivyan. "Palace Theatre, Cambridge Circus", London Theatres Encyclopaedia, Over the Footlights: A History, accessed 18 June 2014

- ^ Simon Louvish (1999). Monkey business. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. pp. 222–23. ISBN 0-312-25292-7.

- ^ Pepys-Whiteley, D. "Courtneidge, Dame (Esmerelda) Cicely (1893–1980)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, January 2011, accessed 8 August 2011 (subscription required)

- ^ a b Thumbnails of programmes from musicals that played at the theatre

- ^ Terry Coleman (2005). Olivier. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. p. 497. ISBN 0-8050-8136-4. Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- ^ a b c Andrew Gans (11 April 2012). "Andrew Lloyd Webber Sells London's Palace Theatre". Playbill. Playbill.com. Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- ^ "Singing in the Rain Extends Booking through February 2013". Palace Theatre. Retrieved 2012-07-12.

- ^ "The Commitments to close in November", Whatsonstage.com, 21 May 2015

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Cursed Child". Harry Potter The Play. harrypottertheplaylondon.com. 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ "'Harry Potter and the Cursed Child' Begins Previews in London, as Magic Continues". The New York Times. 7 June 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ "How to get tickets to Harry Potter and the Cursed Child". whatsonstage.com. 23 October 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Cursed Child extends booking YET AGAIN – this time to May 2017". Digital Spy. 30 October 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ "Ere's How You Can See Harry Potter and the Cursed Child Without Robbing Gringotts", MTV.com, 23 October 2015

- ^ "Details for IoE Listing 208945". English Heritage-Images of England. Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- ^ Fisher, Philip. "Great West End Theatres", British Theatre Guide, 19 February 2012

- ^ Mento, Charles. "The Talons of Weng-Chiang". Doctor Who Reference Guide. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ^ Girvan, Ray. "Full Dark House", JSBookReader, 4 May 2012

- Guide to British Theatres 1750–1950, John Earl and Michael Sell pp. 130 (Theatres Trust, 2000) ISBN 0-7136-5688-3