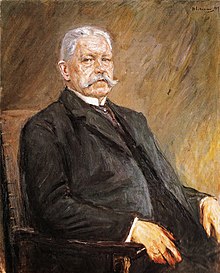

Paul von Hindenburg

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (), known universally as Paul von Hindenburg (German: [ˈpaʊl fɔn ˈhɪndn̩bʊɐ̯k] ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military officer, statesman, and politician who served as the second President of Germany during the period 1925–34.

Hindenburg retired from the army for the first time in 1911, but was recalled shortly after the outbreak of World War I in 1914. He first came to national attention at the age of 66 as the victor of the decisive Battle of Tannenberg in August 1914. As Germany's Chief of the General Staff from August 1916, Hindenburg's reputation rose greatly in German public esteem. He and his deputy Erich Ludendorff would then lead Germany in a de facto military dictatorship throughout the remainder of the war, marginalizing German Emperor Wilhelm II as well as the German Reichstag. In line with Lebensraum ideology, he advocated sweeping annexations of territory in Poland, Ukraine and Russia in order to re-settle Germans there.

Hindenburg retired again in 1919, but returned to public life in 1925 to be elected the second President of Germany. In 1932, although 84 years old and in poor health, Hindenburg was persuaded to run for re-election as German President, as he was considered the only candidate who could defeat Hitler. Hindenburg was re-elected in a runoff. He was opposed to Hitler and was a major player in the increasing political instability in the Weimar Republic that ended with Hitler's rise to power. He dissolved the Reichstag (parliament) twice in 1932 and finally, under pressure, agreed to appoint Hitler Chancellor of Germany in January 1933. In February, he signed off on the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended various civil liberties, and in March he signed the Enabling Act of 1933, which gave Hitler's regime arbitrary powers. Hindenburg died the following year, after which Hitler declared the office of President vacant and made himself head of state.

Early years

Hindenburg was born in Posen, Prussia (Polish: Poznań; until 1793 and since 1919 part of Poland[1]), the son of Prussian aristocrat Robert von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (1816–1902) and his wife Luise Schwickart (1825–1893), the daughter of medical doctor Karl Ludwig Schwickart and his wife Julie Moennich. Hindenburg was embarrassed by his mother's non-aristocratic background and hardly mentioned her at all in his memoirs. His paternal lineage was considered highly distinguished; in fact, he was descended from one of the most respected ancient noble families in Prussia. His paternal grandfather was Otto Ludwig von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (1778–1855), through whom he was remotely descended from the illegitimate daughter of Count Heinrich VI of Waldeck. Hindenburg was also a descendant of Martin Luther and his wife Katharina von Bora through their daughter Margareta Luther. Hindenburg's younger brothers and sister were Otto (born 24 August 1849), Ida (born 19 December 1851) and Bernhard (born 17 January 1859).

German Army

After his education at cadet schools in Berlin and Wahlstatt (now Legnickie Pole), Hindenburg was commissioned as a lieutenant in 1866. He fought in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871. Hindenburg was selected for prestigious duties as a young officer. He served Elisabeth Ludovika, the widow of King Frederick William IV of Prussia, and was present in the Palace of Versailles when the German Empire was proclaimed on 18 January 1871 as one of a group of officers decorated for bravery in battle who had been chosen to represent their regiments. He also served as an Honour Guard prior to the Military funeral of Emperor William I in 1888. He was promoted to captain in 1878, major in 1881, lieutenant-colonel in 1891, colonel in 1893, major-general in 1897 and lieutenant general in 1900. Hindenburg eventually commanded a corps and was promoted to the rank of General of the Infantry in 1903. Meanwhile, he married Gertrud von Sperling (1860–1921), also an aristocrat, by whom he had two daughters, Irmengard Pauline (1880) and Annemaria (1891), and one son, Oskar (1883).

World War I

Hindenburg retired from the army for the first time in 1911, but in 1914 was recalled shortly after the outbreak of World War I by Helmuth von Moltke, the Chief of the German General Staff.

Hindenburg was given command of the Eighth Army, then locked in combat with two Russian armies in East Prussia. After suffering defeat by the Russian First Army at the Battle of Gumbinnen, Hindenburg's predecessor Maximilian von Prittwitz had been planning to abandon East Prussia and retreat behind the River Vistula.

Nonetheless, Hindenburg's Eighth Army was soon victorious at the Battle of Tannenberg and the Battle of the Masurian Lakes against the Russian armies. Although historians such as G.J. Meyer attach much of the credit to Erich Ludendorff and to the then little-known staff officer Max Hoffmann, these successes made Hindenburg a national hero.

At the start of November 1914, Hindenburg was given the position of Supreme Commander East (Ober-Ost), although at this stage his authority only extended over the German, not the Austro-Hungarian, portion of the front, and units were transferred from East Prussia to form a new Ninth Army in south-western Poland. On 27 November 1914, after the Battle of Lodz, Hindenburg was promoted to the rank of Generalfeldmarschall. A further battle was fought by the Eighth and newly-formed Tenth Armies in Masuria that winter. Ober-Ost eventually consisted of the German Eighth, Ninth and Tenth Armies, plus other assorted corps.

Hindenburg and Ludendorff felt that more effort should be made on the Eastern Front to relieve the forces of Germany's ally, the Ottoman Empire, in order to defeat Russia. By contrast, Erich von Falkenhayn, the Chief of the General Staff, felt that it was impossible for Germany to win a decisive victory in this way. He felt that building up forces in the east could not lead to victory in an overall conflict involving two fronts. Indeed, he hoped that Russia might be encouraged to drop out of the war if not pressed too hard. Instead of pursuing an eastern strategy, Falkenhayn unleashed an offensive at Verdun in 1916 in order to "bleed France white"[2] and encourage her to make peace. For his part, Hindenburg was anxious to conquer the Baltic region from the Russian Empire. He recognized the strategic value of controlling its territories in the event of another war with Russia, and he also wished to see it colonized by ethnic Germans.[3]

Though Hindenburg's own military ability is disputed,[4] he had a team of talented and able subordinates who won him a series of great victories on the Eastern Front between 1914 and 1916. These victories transformed Hindenburg into Germany's most popular man.[5] During the war, Hindenburg was the subject of an enormous personality cult. He was seen as the perfect embodiment of German manly honour, rectitude, decency and strength[citation needed]. The appeal of the Hindenburg cult cut across ideological, religious, class and regional lines, but the group that idolized Hindenburg the most was the German right, who saw him as an ideal representative of the Prussian ethos and of Lutheran, Junker values[citation needed]. During the war, there were wooden statues of Hindenburg built all over Germany, onto which people nailed money and cheques for war bonds. It was a measure of Hindenburg's public appeal that when the Government launched an all-out programme of industrial mobilisation in 1916, the programme was named the Hindenburg Programme.[5]

By the summer of 1916, Erich von Falkenhayn had been discredited by the disappointing progress of the Verdun Offensive and the near collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Army caused by the Brusilov Offensive and the entry of Romania into the war on the Allied side. In August, Hindenburg succeeded him as Chief of the General Staff, although real power was exercised by his deputy, Erich Ludendorff. Hindenburg in many ways served as the real commander-in-chief of the German armed forces instead of the emperor, who had been reduced to a mere figurehead, while Ludendorff served as the de facto general chief of staff. From 1916 onwards, Germany became an unofficial military dictatorship, often called the "Silent dictatorship"[5][6] by historians.

In March 1918, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed between Germany and the new Bolshevik government of Russia. It awarded large areas of land in Poland, Ukraine and Russia to Germany. This was in accordance with the Lebensraum concept supported by Hindenburg, which was advocated in parts of the German society and proposed large-scale annexations, ethnic cleansing and Germanization in conquered territories. The concept was enhanced after the war by the Nazis and finally put into effect during World War II.[7][8] Hindenburg was also an advocate of the so-called Polish Border Strip plan, which postulated mass expulsion of Poles and Jews from territories that would be annexed by the German Empire, a foreshadow of the ethnic cleansing carried out decades later.[9][10][11]

In September 1918, Ludendorff advised seeking an armistice with the Allies, but in October, changed his mind and resigned in protest. Ludendorff had expected Hindenburg to follow him by also resigning, but Hindenburg refused on the grounds that in this hour of crisis, he could not desert the men under his command. Ludendorff never forgave Hindenburg for this. Ludendorff was succeeded by Wilhelm Groener. In November 1918, Hindenburg and Groener played a decisive role in persuading the emperor Wilhelm II to abdicate for the greater good of Germany.

Hindenburg, a firm monarchist throughout his life, always regarded this episode with considerable embarrassment, and almost from the moment the emperor abdicated, Hindenburg insisted that he had played no role in it. Instead, he assigned all of the blame to Groener. Groener, for his part, went along in order to protect Hindenburg's reputation.[citation needed]

Aftermath of the war

At the conclusion of the war, Hindenburg retired a second time and announced his intention to retire from public life. In 1919, he was called before a parliamentary commission that was investigating the responsibility for both the outbreak of war in 1914 and for the defeat in 1918.

Hindenburg had not wanted to appear before the commission, and had been subpoenaed. His appearance became an eagerly-awaited public event. Ludendorff, who had fallen out with Hindenburg over the decision to continue seeking the armistice in October 1918, was concerned that Hindenburg might reveal that it was he who had advised seeking an armistice the previous month. Ludendorff wrote a letter to Hindenburg to inform him that he was writing his memoirs and was prepared to expose the fact that Hindenburg did not deserve the credit that he had received for his victories. Ludendorff's letter went on to suggest that Hindenburg's testimony would determine how favorably Ludendorff would present him in his memoirs.

When Hindenburg did appear before the commission, he refused to answer any questions about the responsibility for the German defeat and instead read out a prepared statement that had been reviewed in advance by Ludendorff's lawyer. Hindenburg testified that the German Army had been on the verge of winning the war in the autumn of 1918 and that the defeat had been precipitated by a Dolchstoß ("stab in the back") by disloyal elements on the home front and unpatriotic politicians. Despite being threatened with a contempt citation for refusing to respond to questions, Hindenburg simply walked out of the hearings after reading his statement. Hindenburg's status as a war hero provided him with a political shield; he was never prosecuted.

Hindenburg's testimony constituted the first use of the Dolchstoßlegende, and the term was adopted by nationalist and conservative politicians who sought to blame the socialist founders of the Weimar Republic for the loss of the war. The reviews in the German press that had grossly misrepresented general Frederick Barton Maurice's book, The Last Four Months, contributed to the creation of this myth. Ludendorff made use of the reviews to convince Hindenburg.[12]

In a hearing before the Committee on Inquiry of the National Assembly on 18 November 1919, a year after the war's end, Hindenburg declared, "As an English general has very truly said, the German Army was 'stabbed in the back'."[12]

Afterwards, Hindenburg had his memoirs ghost-written in 1919–20. The result, Mein Leben (My Life), was a huge bestseller in Germany, but was dismissed by most military historians and critics as a boring apologia that skipped over the most controversial issues in Hindenburg's life. Afterwards, Hindenburg retired from most public appearances and spent most of his time with his family. A widower, Hindenburg was very close to his only son, Major Oskar von Hindenburg, and his granddaughters.

Presidency

1925 election

In 1925, Hindenburg was urged to run for the office of President of Germany. In spite of his lack of interest in holding public office, he decided to stand for the post anyway. In the first round of the presidential election held on 29 March 1925, no candidate had emerged with a majority and a run-off election had been called. The Social Democratic candidate, Otto Braun, the Prime Minister of Prussia, had agreed to drop out of the race and had endorsed the Catholic Centre Party's candidate, Wilhelm Marx. Since Karl Jarres, the joint candidate of the two conservative parties, the German People's Party (DVP) and the German National People's Party (DNVP), was regarded as too dull, it seemed likely that Marx would win. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, one of the leaders of the DNVP, visited Hindenburg and urged him to run.

Hindenburg initially demurred, but under strong pressure from Tirpitz applied over several meetings, he broke down and agreed to run. Though Hindenburg ran during the second round of the elections as a non-party independent, he was generally regarded as the conservative candidate. Largely because of his status as Germany's greatest war hero, Hindenburg won the election in the second round of voting held on 26 April 1925. He was aided by the support of the Bavarian People's Party (BVP), which switched from supporting Marx, and the refusal of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) to withdraw its candidate, Ernst Thälmann (if either had supported Marx, he would have won).[13]

First term

Hindenburg took office on 12 May 1925. For the first five years after taking office, Hindenburg generally refused to allow himself to be drawn into the maelstrom of German politics in the period, and sought to play the role of a republican equivalent of a constitutional monarch. Although often referred to as the Ersatzkaiser (substitute Emperor), Hindenburg made no effort to restore the monarchy and took his oath to the Weimar Constitution seriously. In 1927, he shocked international opinion by defending Germany's actions and entry in World War I. Specifically, he declared that Germany entered the war as "the means of self-assertion against a world full of enemies. Pure in heart we set off to the defence of the fatherland and with clean hands the German army carried the sword."[14]

In private, Hindenburg often complained to his associates that he missed the quiet of his retirement and bemoaned that he had allowed himself to be pressured into running for president. Hindenburg carped that politics was full of issues such as economics that he did not understand, and did not want to. He was surrounded by a coterie of advisers antipathetic to the Weimar constitution. These advisers included his son, Oskar, Otto Meißner, and General Kurt von Schleicher. This group were known as the Kamarilla. The younger Hindenburg served as his father's aide-de-camp and controlled politicians' access to the President.[citation needed]

Schleicher was a close friend of Oskar and came to enjoy privileged access to Hindenburg. It was he who came up with the idea of Presidential government based on the so-called "25/48/53 formula". Under a "Presidential" government the head of government (in this case, the chancellor), is responsible to the head of state, and not a legislative body. The "25/48/53 formula" referred to the three articles of the Constitution that could make a "Presidential government" possible:

- Article 25 allowed the President to dissolve the Reichstag.

- Article 48 allowed the president to sign into law emergency bills without the consent of the Reichstag. However, the Reichstag could cancel any law passed by Article 48 by a simple majority within sixty days of its passage.

- Article 53 allowed the president to appoint the chancellor.

Schleicher's idea was to have Hindenburg appoint a man of Schleicher's choosing as chancellor, who would rule under the provisions of Article 48. If the Reichstag should threaten to annul any laws so passed, Hindenburg could counter with the threat of dissolution. Hindenburg was unenthusiastic about these plans, but was pressured into going along with them by his son along with Meißner and Schleicher.[citation needed]

Presidential government

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2013) |

The first attempt to establish a "presidential government" occurred in 1926–27, but floundered for lack of political support. During the winter of 1929–30, however, Schleicher had more success. After a series of secret meetings attended by Meißner, Schleicher, and Heinrich Brüning, the parliamentary leader of the Catholic Center Party (Zentrum), Schleicher and Meißner were able to persuade Brüning to go along with a scheme for "presidential government". How much Brüning knew of Schleicher's ultimate objective of dispensing with democratic governance is unclear. Schleicher maneuvered to exacerbate a bitter dispute within the "Grand Coalition" government of the Social Democrats and the German People's Party over whether the unemployment insurance rate should be raised by a half percentage point or a full percentage point. The upshot of these intrigues was the fall of Müller's government in March 1930 and Hindenburg's appointment of Brüning as Chancellor.

Brüning's first official act was to introduce a budget calling for steep spending cuts and steep tax increases. When the budget was defeated in July 1930, Brüning arranged for Hindenburg to sign the budget into law by invoking Article 48. When the Reichstag voted to repeal the budget, Brüning had Hindenburg dissolve the Reichstag, just two years into its mandate, and reapprove the budget through the Article 48 mechanism. In the September 1930 elections the Nazis achieved an electoral breakthrough, gaining 17 percent of the vote, up from 2 percent in 1928. The Communist Party of Germany also made striking gains, albeit not so great.

After the 1930 elections, Brüning continued to govern largely through Article 48; his government was kept afloat by the support of the Social Democrats who voted not to cancel his Article 48 bills in order not to have another election that could only benefit the Nazis and the Communists. Hindenburg for his part grew increasingly annoyed at Brüning, complaining that he was growing tired of using Article 48 all the time to pass bills. Hindenburg found the detailed notes that Brüning submitted explaining the economic necessity of each of his bills to be incomprehensible. Brüning continued with his policies of raising taxes and cutting spending to address the onset of the Great Depression; the only areas in which government spending increased were the military budget and the subsidies for Junkers in the so-called Osthilfe (Eastern Aid) program. Both of these spending increases reflected Hindenburg's concerns.

In October 1931, Hindenburg and Adolf Hitler met for the very first time in a high-level conference in Berlin over Nazi Party politics among Hindenburg's cabinet members. There were clear signs of tension throughout the meeting as it became evident to everyone present that both men took an immediate dislike to each other. Afterwards, Hindenburg often disparagingly referred to Hitler in private as "that Austrian corporal", or "that Bohemian corporal" or sometimes just simply as "the corporal".[15][16] For his part, Hitler often disparagingly referred to Hindenburg in private as "that old fool" or "that old reactionary". Until January 1933, Hindenburg often stated that he would never appoint Hitler as chancellor under any circumstances. On 26 January 1933, Hindenburg privately told a group of his friends: "Gentlemen, I hope you will not hold me capable of appointing this Austrian corporal to be Reich Chancellor".[17]

January 1932 – January 1933: A critical period

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2013) |

By January 1932, at the age of 84, Hindenburg was lapsing in and out of senility and wanted to leave office as soon as his seven-year presidential term was over. Nonetheless, he was persuaded to run for re-election in the German presidential election of 1932 by the Kamarilla as well as by the Centre, the liberals and the Social Democratic Party (SDP). The SDP regarded Hindenburg as the only man who could defeat Hitler and keep the Nazi Party from winning the elections (and they said so throughout the campaign); they also expected him to keep Brüning in office.[18] Hindenburg reluctantly agreed to stay in office, but wanted to avoid an election. The only way this was possible was for the Reichstag to vote to cancel the election with a two-thirds supermajority. Since the Nazis were the second-largest political party, their co-operation was vital if this was to be done. Brüning met with Hitler in January 1932 to ask if he would agree to President Hindenburg's demand to forgo the presidential election. Surprisingly, Hitler supported the measure, but with one major condition: dissolve the Reichstag and hold new parliamentary elections.

Brüning rejected Hitler's demands as totally outrageous and unreasonable. By this time, Schleicher had decided that Brüning had become an obstacle to his plans and was already plotting Brüning's downfall. Schleicher convinced Hindenburg that the reason why Hitler had rejected Brüning's offer was because Brüning had deliberately sabotaged the talks to force the elderly president into a grueling re-election battle. During the election campaign of 1932, Brüning campaigned hard for Hindenburg's re-election. As Hindenburg was in bad health and a poor speaker in any case, the task of traveling the country and delivering speeches for Hindenburg had fallen upon Brüning. Hindenburg's campaign appearances usually consisted simply of him appearing before crowds and waving to them without speaking.

In the first round of the German presidential election of 1932, held in March, Hindenburg emerged as the frontrunner, but failed to gain a majority. In the runoff election of April 1932, Hindenburg defeated Hitler for the presidency.[19] After the presidential elections had ended, Schleicher held a series of secret meetings with Hitler in May 1932 and thought that he had obtained a "gentleman's agreement" in which Hitler had agreed to support the new "presidential government" that Schleicher was building. At the same time, Schleicher, with Hindenburg's complicit consent, set about undermining Brüning's government.

The first blow occurred in May 1932, when Schleicher had Hindenburg dismiss Groener as Defense Minister in a way that was designed to humiliate both Groener and Brüning. On 31 May 1932, Hindenburg dismissed Brüning as chancellor and replaced him with the man that Schleicher had suggested, Franz von Papen. "The Government of Barons", as Papen's government was known, openly had as its objective the destruction of German democracy. Like Brüning's government, Papen's government was a "presidential government" that governed through the use of Article 48.

Unlike Brüning, Papen ingratiated himself with Hindenburg and his son through flattery. Much to Schleicher's annoyance, Papen quickly replaced him as Hindenburg's favorite advisor. The French Ambassador André François-Poncet reported to his superiors in Paris that "It's he [Papen] who is the preferred one, the favorite of the Marshal; he diverts the old man through his vivacity, his playfulness; he flatters him by showing him respect and devotion; he beguiles him with his daring; he is in [Hindenburg's] eyes the perfect gentleman."[20]

In accordance with Schleicher's "gentleman's agreement", Hindenburg dissolved the Reichstag and set new elections for July 1932. Schleicher and Papen both believed that the Nazis would win the majority of the seats and would support Papen's government. Hitler staged an electoral comeback, with his Nazi Party winning a solid plurality of seats in the Reichstag. Following the Nazi electoral triumph in the Reichstag elections held on 31 July 1932, there were widespread expectations that Hitler would soon be appointed Chancellor. Moreover, Hitler repudiated the "gentleman's agreement" and declared that he wanted the Chancellorship for himself. In a meeting between Hindenburg and Hitler held on 13 August 1932, in Berlin, Hindenburg firmly rejected Hitler's demands for the chancellorship.

The minutes of the meeting were kept by Otto Meißner, the Chief of the Presidential Chancellery. According to the minutes,

Herr Hitler declared that, for reasons which he had explained in detail to the Reich President that morning, his taking any part in cooperation with the existing government was out of the question. Considering the importance of the National Socialist movement, he must demand the full and complete leadership of the government and state for himself and his party.

The Reich President in reply said firmly that he must answer this demand with a clear, unyielding "No". He could not justify before God, before his conscience, or before the Fatherland the transfer of the whole authority of government to a single party, especially to a party that was biased against people who had different views from their own. There were a number of other reasons against it, upon which he did not wish to enlarge in detail, such as fear of increased unrest, the effect on foreign countries, etc.

Herr Hitler repeated that any other solution was unacceptable to him.

To this the Reich President replied: "So you will go into opposition?"

Hitler: "I have now no alternative".[21]

After refusing Hitler's demands for the chancellorship, Hindenburg had a press release issued about his meeting with Hitler that implied that Hitler had demanded absolute power and had his knuckles rapped by the president for making such a demand. Hitler was enraged by this press release. However, given Hitler's determination to take power lawfully, Hindenburg's refusal to appoint him as chancellor was an impassable quandary for Hitler.

When the Reichstag convened in September 1932, its only act was to pass a massive vote of no-confidence in Papen's government. In response, Papen had Hindenburg dissolve the Reichstag for elections in November 1932. The second Reichstag elections saw the Nazi vote drop from 37 percent to 32 percent, though the Nazis once again remained the largest party in the Reichstag. After the November elections, there ensued another round of fruitless talks between Hindenburg, Papen, Schleicher on the one hand and Hitler and the other Nazi leaders on the other.

The president and chancellor wanted Nazi support for the "Government of the President's Friends"; at most, they were prepared to offer Hitler the meaningless office of vice-chancellor. On 24 November 1932, during the course of another Hitler-Hindenburg meeting, Hindenburg stated his fears that "a presidential cabinet led by Hitler would necessarily develop into a party dictatorship with all its consequences for an extreme aggravation of the conflicts within the German people".[17]

Hitler, for his part, remained adamant that Hindenburg give him the chancellorship and nothing else. These demands were incompatible and unacceptable to both sides and the political stalemate continued. To break the stalemate, Papen proposed that Hindenburg declare martial law and do away with democracy, effecting a presidential coup. Papen won over Hindenburg's son Oskar with this idea, and the two persuaded Hindenburg for once to forgo his oath to the constitution and to go along with this plan. Schleicher, who had come to see Papen as a threat, blocked the martial law move by unveiling the results of a war games exercise that showed if martial law was declared, the Nazi Sturmabteilung and the Communist Red Front Fighters would rise up, the Poles would invade, and the Reichswehr would be unable to cope.

Whether this was the honest result of a war games exercise or just a fabrication by Schleicher to force Papen out of office is a matter of some historical debate. The opinion of most leans towards the latter, for in January 1933 Schleicher would tell Hindenburg that new war games had shown the Reichswehr would crush both the Sturmabteilung and the Red Front Fighters and defend the eastern borders of Germany from a Polish invasion. The results of the war games forced Papen to resign in December 1932 in favor of Schleicher. Hindenburg was most upset at losing his favorite chancellor. Suspecting that the war games were faked to force Papen out, he came to bear a grudge against Schleicher.

Papen, for his part, was determined to get back into office, and on 4 January 1933 he met Hitler to discuss how they could bring down Schleicher's government, though the talks were inconclusive largely because Papen and Hitler each coveted the chancellorship for himself. However, Papen and Hitler agreed to keep talking. Ultimately, Papen came to believe that he could control Hitler from behind the scenes and decided to support him as the new chancellor. Papen then persuaded Meißner and the younger Hindenburg of the merits of his plan, and the three then spent the second half of January pressuring Hindenburg into naming Hitler as chancellor. Hindenburg loathed the idea of Hitler as chancellor and preferred that Papen hold that office instead.

However, the pressure from Meißner, Papen, and the younger Hindenburg was relentless, and by the end of January, the president decided to appoint Hitler chancellor. After Schleicher as well despaired of his efforts to get hold of the situation, Hindenburg accepted his resignation with the words, "Thanks, General, for everything you have done for the Fatherland. Now let's have a look at which way, with God's help, the cat will keep on jumping." Hitler threatened Hindenburg to make him chancellor or to make him leader of the Reichstag. Finally, the 85-year-old Hindenburg agreed to make Hitler chancellor, and on the morning of 30 January 1933, Hindenburg swore him in as chancellor at the presidential palace.[15]

The Machtergreifung

Hindenburg played the key role in the Nazi Machtergreifung (Seizure of Power) in 1933 by appointing Hitler chancellor of a "Government of National Concentration", even though the Nazis were in the minority in cabinet. The only Nazi ministers were Hitler himself, Hermann Göring and Wilhelm Frick. Frick held the then-powerless Interior Ministry (unlike the rest of Europe, at the time the Interior Ministry had no power over the police), while Göring was given no portfolio. Most of the other ministers were survivors from the Papen and Schleicher governments, and the ones who were not, such as Alfred Hugenberg of the German National People's Party (DNVP), were not Nazis. This had the effect of assuring Hindenburg that the room for radical moves on the part of the Nazis was limited. Moreover, Hindenburg's favorite politician, Papen, was Vice Chancellor of the Reich and Minister-President of Prussia, and Hindenburg agreed not to hold any meetings with Hitler unless Papen was present as well.

Hitler's first act as chancellor was to ask Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag, so that the Nazis and DNVP could win an outright majority. Hindenburg agreed to this request. In early February 1933, Papen asked for and received an Article 48 bill signed into law that sharply limited freedom of the press. After the Reichstag fire on 27 February, Hindenburg, at Hitler's urging, signed into law the Reichstag Fire Decree, which effectively suspended all civil liberties in Germany.

At the opening of the new Reichstag on 21 March 1933, at the Garrison Church in Potsdam,[22] the Nazis staged an elaborate ceremony in which Hindenburg played the leading part, appearing alongside Hitler during an event orchestrated to mark the continuity between the old Prussian-German tradition and the new Nazi state. He said, in part, "May the old spirit of this celebrated shrine permeate the generation of today, may it liberate us from selfishness and party strife and bring us together in national self-consciousness to bless a proud and free Germany, united in herself." Hindenburg's apparent stamp of approval had the effect of reassuring many Germans, especially conservative Germans, that life would be fine under the new regime.

On 23 March 1933, Hindenburg signed the Enabling Act of 1933 into law, which gave decrees issued by the cabinet (in effect, Hitler) the force of law.

During 1933 and 1934, Hitler was very aware of the fact that Hindenburg, as President and supreme commander of the armed forces, was now the only check on his power. With the passage of the Enabling Act and the banning of all parties other than the Nazis, Hindenburg's power to dismiss Hitler from office was effectively the only remedy by which he could be legally dismissed. Given that Hindenburg was still a popular war hero and a revered figure in the ("Reichswehr"), there was little doubt that the Reichswehr would side with Hindenburg if he ever decided to sack Hitler. Thus, as long as Hindenburg was alive, Hitler was always very careful to avoid offending him or the Army. Although Hindenburg was in increasingly bad health, the Nazis made sure that whenever Hindenburg did appear in public it was in Hitler's company. During these appearances, Hitler always made a point of showing him the utmost respect and deference. However, in private, Hitler continued to detest Hindenburg, and expressed his hope that "the old reactionary" would hurry up and die as soon as possible.

The only time that Hindenburg ever objected to a Nazi bill occurred in early April 1933, when the Reichstag passed a Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service that called for the immediate dismissal of all Jewish civil servants at the Reich, Land, and municipal levels. Hindenburg resented this bill in case it was not amended to exclude all Jewish veterans of World War I, Jewish civil servants who served in the civil service during the war and those Jewish civil servants whose fathers were veterans. Hitler amended the bill to meet Hindenburg's objections.[23][24]

During the summer of 1934, Hindenburg grew increasingly alarmed at Nazi excesses. With his support, Papen gave a speech at the University of Marburg on 17 June calling for an end to state terror and the restoration of some freedoms. When Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels got wind of it, he not only barred its broadcast, but ordered the seizure of newspapers in which part of the text was printed. A furious Papen immediately notified Hindenburg, who told Blomberg to give Hitler an ultimatum; unless Hitler took steps to end the growing tension in Germany, he would dismiss Hitler and turn the government over to the army. Not long afterward, Hitler carried out the Night of the Long Knives, for which he received the personal thanks of Hindenburg.[25]

Death

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2015) |

Hindenburg remained in office until his death at the age of 86 from lung cancer at his home in Neudeck, East Prussia, on 2 August 1934. On August 1, Hitler had got word that Hindenburg was on his deathbed. He then had the cabinet pass the "Law Concerning the Highest State Office of the Reich," which stipulated that upon Hindenburg's death, the offices of president and chancellor would be merged under the title of Leader and chancellor (Führer und Reichskanzler).[26] Two hours after Hindenburg's death, it was announced that as a result of this law, Hitler was now both Germany's head of state and head of government, thereby completing the progress of Gleichschaltung ("Co-ordination"). This action effectively removed all institutional checks and balances on Hitler's power. Hitler had made plans almost as soon as he took complete power to seize the powers of the president for himself as soon as Hindenburg died. He had known as early as the spring of 1934 that Hindenburg would likely not survive the year and had been working feverishly to get the armed forces—the only group in Germany that was nearly powerful enough to remove him with Hindenburg gone—to support his bid to become Hindenburg's successor. Indeed, he had agreed to suppress the SA in return for the Army's support.

Hitler had a plebiscite held on 19 August 1934, in which the German people were asked if they approved of Hitler merging the two offices. The Ja (Yes) vote amounted to 90% of the vote.

| Silver 5 mark commemorative coin of Paul von Hindenburg, struck 1936 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Obverse: Paul von Hindenburg, 1847–1934 | Reverse: (German) Deutsches Reich, 5 RM |

In taking over the president's powers for himself without calling for a new election, Hitler technically violated the Enabling Act. While the Enabling Act allowed Hitler to pass laws that contravened the Weimar Constitution, it specifically forbade him from interfering with the powers of the president. Moreover, the Weimar Constitution had been amended in 1932 to make the president of the High Court of Justice, not the chancellor, acting president pending a new election. However, Hitler had become law unto himself by this time, and no one dared object.

Hindenburg himself was said to be a monarchist who favored a restoration of the German monarchy. Though he hoped one of the Prussian princes would be appointed to succeed him as head of state, he did not attempt to use his powers in favour of such a restoration, as he considered himself bound by the oath he had sworn on the Weimar Constitution.

At the Nuremberg trials, it was alleged by Franz von Papen in 1945 and Baron Gunther von Tschirschky that Hindenburg's "political testament" asked for Hitler to restore the monarchy. However, the truth of this story cannot be established because Oskar von Hindenburg destroyed the portions of his father's will relating to politics.

Burial, removal and reburial

Hitler ordered his architect, Albert Speer, to take care of the background for the funeral ceremony at the Tannenberg Memorial in East Prussia. As Speer later recalled: "I had a high wooden stand built in the inner courtyard. Decorations were limited to banners of black crepe hung from the high towers that framed the inner courtyard...On the eve of the funeral the coffin was brought on a gun carriage from Neudeck, Hindenburg's East Prussian estate, to one of the towers of the monument. Torchbearers and the traditional flags of German regiments of the First World War accompanied it; not a single word was spoken, not a command given. This reverential silence was more impressive than the organized ceremonial of the following days."[27]

Hindenburg's remains were moved six times in the 12 years following his initial interment.

Hindenburg was originally buried in the yard of the castle-like Tannenberg Memorial near Tannenberg, East Prussia (now Stębark, Poland) on 7 August 1934 during a large state funeral, five days after his death. This was against the wishes he had expressed during his life: to be buried in his family plot in Hanover, Germany, next to his wife Gertrud, who had died in 1921.

The following year, Hindenburg's remains were temporarily disinterred, along with the bodies of 20 unknown German soldiers buried at the Tannenberg Memorial, to allow the building of his new crypt there (which required lowering the entire plaza 8 feet (2.4 m)). Hindenburg's bronze coffin was placed in the crypt on 2 October 1935 (the anniversary of his birthday), along with the coffin bearing his wife, which was moved from the family plot.[28]

In January 1945, as Soviet forces advanced into East Prussia, Hitler ordered both coffins to be disinterred for their safety. They were first moved to a bunker just outside Berlin, then to a salt mine at the village of Bernterode, Germany, along with the remains of both Frederick Wilhelm I of Prussia and Frederick II of Prussia (Frederick the Great). The four coffins were hastily marked of their contents using red crayon, and interred behind a 6-foot-thick (1.8 m) masonry wall in a deep recess of the 14-mile (23 km) mine complex, 1,800 feet (550 m) underground. Three weeks later, on 27 April 1945, the coffins were discovered by U.S. Army Ordnance troops after tunneling through the wall. All were subsequently moved to the basement of the heavily guarded Marburg Castle in Marburg an der Lahn, Germany, a collection point for recovered Nazi plunder.

The U.S. Army, in a secret project dubbed "Operation Bodysnatch", had many difficulties in determining the final resting places for the four famous Germans. Sixteen months after the salt mine discovery, in August 1946, the remains of Hindenburg and his wife were finally laid to rest by the American army at St. Elizabeth's, a 13th-century church built by the Teutonic Knights in Marburg, Hesse, where they remain today.[29][30]

A colossal statue of Hindenburg, erected at Hohenstein (now Olsztynek, Poland) in honor of his defeat of the Russians was demolished by the Germans in 1944 to prevent its desecration by the advancing Soviet Army.[31]

Legacy

The famed zeppelin Hindenburg that was destroyed by fire in 1937 was named in his honor, as was the Hindenburgdamm, a causeway joining the island of Sylt to mainland Schleswig-Holstein that was built during his time in office. The previously Upper Silesian town of Zabrze (Template:Lang-de) was also renamed after him in 1915, as well as the SMS Hindenburg, a battlecruiser commissioned in the Imperial German Navy in 1917 and the last capital ship to enter service in the Imperial Navy. The Hindenburg Range in New Guinea, which includes the world's largest cliff, the Hindenburg Wall, also bears his name.

Decorations and awards

- German

- Knight of the Black Eagle Order

- Grand Commander of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern with Swords

- Pour le Mérite (2 September 1914); Oak Leaves added on 23 February 1915

- Iron Cross, 1st and 2nd class

- Grand Cross of the Iron Cross (9 December 1916); Golden Star added on 25 March 1918 (Star of the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Military Order of Max Joseph (Bavaria)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Military Order of St. Henry (Saxony)

- Knight of the Order of Military Merit (Württemberg)

- Knight Grand Cross with Crown, Swords and Laurel of the House and Merit Order of Peter Frederick Louis (Oldenburg)

- Military Merit Cross, 1st class (Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin)

- Friedrich Cross, 1st class (Duchy of Anhalt)

- Honorary Commander of the Order of Saint John (Bailiwick of Brandenburg)

- Foreign

- Grand Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa (Austria)

- Cross of Military Merit, 1st class with war decoration (Austria-Hungary)

- Gold Medal of Military Merit ("Signum Laudis", Austria-Hungary)

- Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece (Spain)[32]

See also

- German presidential election, 1925

- German presidential election, 1932

- German Reichsmark, coin.

- Hindenburg light

- List of people on the cover of Time Magazine: 1920s − 22 March 1926

References

- ^ Mapa.szukacz.pl – Mapa Polski z planami miast at mapa.szukacz.pl

- ^ Horne, Alistair (1964). The Price of Glory: Verdun 1916. Penguin Books. pp. 44–49.

- ^ Grimsley, Mark; Rogers, Clifford J. (2002). Civilians in the Path of War. Studies in War, Society, and the Military. University of Nebraska Press. p. 172.

- ^ Pöhlmann, Markus (2012). "Krise und Karriere". Damals (in German). Vol. 44, no. 8. pp. 22–27.

{{cite magazine}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Müller, Christian Th. (2012). "Von Tannenberg zur 'stillen Diktatur'". Damals (in German). 44 (8): 28–35.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Corvisier, André; Childs, John (1994). A dictionary of military history and the art of war. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 357.

- ^ Guide to International Relations and Diplomacy edited by Michael Graham Fry, Erik Goldstein,Richard Langhorne page 422 Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd 2004

- ^ The Ideological Origins of Nazi Imperialism Woodruff D. Smith page 189

- ^ Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany Isabel V. Hull page 200

- ^ Ethnische "Sauberungen" in Der Moderne Globale Wechselwirkungen Nationalistischer Und Rassistischer Gewaltpolitik Im 19. Und 20. Jahrhundert Michael Schwartz page 181

- ^ A Companion to World War I John Horne page 452

- ^ a b William L. Shirer, The Rise and fall of the Third Reich, Simon and Schuster (1960) p. 31

- ^ Evans, Richard J., The Coming of the Third Reich, p. 82

- ^ Goebel, Stefan (2007). The Great War and Medieval Memory: War, Remembrance and Medievalism in Britain and Germany, 1914–1940. Studies in the Social and Cultural History of Modern Warfare. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-521-85415-3.

- ^ a b Goltz, Anna von der, Hindenburg, p. 168

- ^ Reference or term first used on 10 October 1931 by Paul von Hindenburg after his first biography (March 1931), on mistaking Hitler's birth town of Braunau (Austria) for that of Braunau in Bohemia. Book Ref: "Adolf Hitler. Das Zeitalter der Verantwortungslosigkeit." Author: Konrad Heiden, Publisher: Europa Verlag, Zurich, 1936, in German.

- ^ a b Jäckel, Eberhard Hitler in History, p. 8

- ^ Evans, Richard J., The Coming of the Third Reich, p. 279

- ^ Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Simon and Schuster, 1959, pp. 158–159

- ^ Turner, Henry Hitler's Thirty Days to Power p. 41

- ^ Noakes, Jeremy; Pridham, Geoffrey, eds. (1983). Nazism 1919–1945. Vol. 1 The Rise to Power 1919–1934. Department of History and Archaeology, University of Exeter. pp. 104–105.

- ^ Shirer, William (1959). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. p. 196.

- ^ "Correspondence Between Hindenburg and Hitler concerning Jewish veterans (Yad Vashem Archive, JM/2462)" (PDF).

- ^ "Hindenburgs letter in the original German" (PDf). Justiz.sachsen.de. p. 28.

- ^ William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (Touchstone Edition) (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990)

- ^ Overy, Richard. The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia. London: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0393020304.

- ^ Speer, Albert (1970). Inside the Third Reich. Orion Books. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-84212-735-3.

- ^ Gessner, Peter K. "Tannenberg: a Monument of German Pride". University at Buffalo. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ Lang, Will (6 March 1950). "The Case of the Distinguished Corpses". Life.

- ^ Alford, Kenneth D. (2000). Nazi Plunder: Great Treasure Stories of World War II. Da Capo Press. p. 101.

- ^ Norman Davies (1981). God's Playground: A History of Poland. 1795 to the present. Clarendon Press. p. 528.

- ^ Awarded in 1931 as German head of state.

Sources

- Asprey, Robert (1991). The German High Command at War: Hindenburg and Ludendorff Conduct World War I. New York, New York: W. Morrow.

- Dorpalen, Andreas (1964). Hindenburg and the Weimar Republic. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Eschenburg, Theodor (1972). "The Role of the Personality in the Crisis of the Weimar Republic: Hindenburg, Brüning, Groener, Schleicher". In Holborn, Hajo (ed.). Republic to Reich – The Making Of The Nazi Revolution. New York: Pantheon Books. pp. 3–50.

- Evans, Richard J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9648-X.

- Feldman, G.D. (1966). Army, Industry and Labor in Germany, 1914–1918. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Jäckel, Eberhard (1984). Hitler in History. Hanover N.H.: Brandeis University Press.

- Kershaw, Sir Ian (1998). "1889–1936: Hubris". Hitler (German ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 659.

- Kitchen, Martin (1976). The Silent Dictatorship: The Politics of the High Command under Hindenburg and Ludendorff, 1916–1918. London: Croom Helm.

- Turner, Henry Ashby (1996). Hitler's Thirty Days to Power : January 1933, Reading, Mass. Addison-Wesley.

- von der Goltz, Anna (2009). Hindenburg: Power, Myth, and the Rise of the Nazis. Oxford, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Wheeler-Bennett, Sir John (1967) [1936]. Hindenburg: the Wooden Titan. London: Macmillan.

Historiography and memory

- Von der Goltz, Anna. Hindenburg: Power, Myth, and the Rise of the Nazis (Oxford University Press, 2009)

In German

- Bracher, Karl Dietrich (1971). Die Aufloesung der Weimarer Republik; eine Studie zum Problem des Machtverfalls in der Demokratie. Villingen, Schwarzwald: Ring-Verlag.

- Görlitz, Walter (1953). Hindenburg: Ein Lebensbild. Bonn: Athenäeum.

- Görlitz, Walter (1935). Hindenburg, eine Auswahl aus Selbstzeugnissen des Generalfeldmarschalls und Reichpräsidenten. Bielefeld: Velhagen & Klasing.

- Hiss, O.C. (1931). Hindenburg: Eine Kleine Streitschrift. Potsdam: Sans Souci Press.

- Maser, Werner (1990). Hindenburg: Eine politische Biographie. Rastatt: Moewig.

External links

Media related to Paul von Hindenburg at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Paul von Hindenburg at Wikimedia Commons- Works by Paul von Hindenburg at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Paul von Hindenburg at the Internet Archive

- http://www.dhm.de/lemo/html/biografien/HindenburgPaul/index.html (German only, some photos)

- Out Of My Life by Paul von Hindenburg at archive.org alternative version

- Date of retirement

- Historical film documents on Paul von Hindenburg at www.europeanfilmgateway.eu

- Use dmy dates from October 2011

- 1847 births

- 1934 deaths

- Paul von Hindenburg

- People from Poznań

- Field marshals of Prussia

- Field marshals of the German Empire

- German military personnel of the Franco-Prussian War

- German military personnel of World War I

- German anti-communists

- German monarchists

- German untitled nobility

- German Lutherans

- People from the Province of Posen

- Prussian people of the Austro-Prussian War

- Presidents of Germany

- People of the Weimar Republic

- Knights of the Golden Fleece

- Recipients of the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross

- Recipients of the Iron Cross (1870), 1st class

- Grand Crosses of the Military Order of Max Joseph

- Recipients of the Order of the Black Eagle

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (military class)

- Recipients of the Friedrich Cross

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Cross of Vytis

- Grand Commanders of the House Order of Hohenzollern

- Grand Crosses of the Military Order of St. Henry

- Independent politicians in Germany

- Knights of the Military Merit Order (Württemberg)

- Recipients of the House and Merit Order of Peter Frederick Louis

- Recipients of the Military Merit Cross (Mecklenburg-Schwerin), 1st class

- Burials at St. Elizabeth's Church, Marburg

- Deaths from lung cancer

- Deaths from cancer in Germany