Pawnee people

| File:Pawnee flag.svg Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma tribal flag | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 5,600 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Pawnee | |

| Religion | |

| Native American Church, Christianity, Traditional Tribal Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Caddo, Kitsai, Wichita, Arikara |

The Pawnee are a Plains Indian tribe who are headquartered in Pawnee, Oklahoma. Historically, they lived in Nebraska and Kansas.[1] In the Pawnee language, the Pawnee people refer to themselves as Chaticks si Chaticks or "Men of Men."[2]

Historically, the Pawnee lived in large earth lodge villages with adjacent farmlands. They used tipis when traveling. With the arrival of horses, the Pawnee retained their agricultural lifestyle, with the tribal economic activities throughout the year alternating between farming crops and hunting buffalo.

In the early 19th century, the Pawnee numbered over 10,000 people and were one of the largest and most powerful tribes in the west. Although dominating the Missouri and Platte areas for centuries, they later suffered from increasing encroachment and attrition by their numerically superior, nomadic enemies the Lakota and Cheyenne and were occasionally at war with the Comanche farther south. They had suffered many losses due to diseases brought by the expanding Europeans. By 1860, the Pawnee population was reduced to 4000. It further decreased, because of disease, crop failure and warfare, to approximately 2400 by 1873, after which time they were forced to move to Indian Territory in Oklahoma. Many Pawnee warriors enlisted to serve as Indian scouts in the US Army to track and fight their tribal enemies resisting European-American expansion on the Great Plains.

Government

There are approximately 3200 enrolled Pawnee and nearly all reside in Oklahoma. Their tribal headquarters is in Pawnee, Oklahoma, and their tribal jurisdictional area is in parts of Noble, Payne, and Pawnee counties. The tribal constitution establishes the government of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma. This government consists of the Resaru Council, the Pawnee Business Council, and the Supreme Court. Enrollment into the tribe requires a minimum 1⁄8th blood quantum.[3]

The Resaru Council, also known as the "Chiefs Council" consists of eight members, each serving four-year terms. Each band has two representatives on the Resaru Council selected by the members of the tribal bands, Cawi, Kitkahaki, Pitahawirata and Ckiri. The Resaru Council has the right to review all acts of the Pawnee Business Council regarding the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma membership and Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma claims or rights growing out of treaties between the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma and the United States according to provision listed in the Pawnee Nation Constitution.

2013-2017

- Morgan Littlesun, 1st Chief Kitkehahki Band

- Ralph Haymond, 2nd Chief Kitkehahki Band, 2nd Nasharo Council Chief

- Matt Reed, 2nd Chief Chaui Band

- Pat Leading Fox, Sr., 1st Chief Skidi Band

- Jimmy Horn, 1st Chief Chaui Band, Nasharo Council Treasurer

- Warren Pratt, Jr., 2nd Chief Skidi Band, Nasharo Council 1st Chief

- Francis Morris, 1st Chief Pitahauirata Band

- Lester Moon Eagle, 2nd Chief Pitahauirata Band, Nasharo Council Secretary

Current

- Morgan Littlesun, 2nd Chief Kitkahaki Band

- Ralph Haymond, Jr., 1st Chief Kitkahaki Band

- Matt Reed, 1st Chief Cawi Band

- Jimmy Horn, 2nd Chief Cawi Band

- Pat Leading Fox, Sr., 2nd Chief, Ckiri Band

- Warren Pratt, Jr., 1st Chief, Ckiri Band

- Ron Rice, Sr. 1st Chief, Pitahawirata Band

- Tim Jim, 2nd Chief, Pitahawirata Band

The Pawnee Business Council is the supreme governing body of the Pawnee Tribe of Oklahoma. Subject to the limitations imposed by the Constitution and applicable Federal law, the Pawnee Business Council shall exercise all the inherent, statutory, and treaty powers of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma by the enactment of legislation, the transaction of business, and by otherwise speaking or acting on behalf of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma on all matters which the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma is empowered to act, including the authority to hire legal counsel to represent the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma.

Current Pawnee Business Council:

- Bruce Pratt, President

- Darrell Wildcat, Vice President

- Phammie N. Littlesun, Treasurer

- Angela Thompson, Secretary

- Council Seat #1

- Council Seat #2

- Council Seat #3

- Council Seat #4

The new Council members were voted in by the people; elections are held every two years on the first Saturday in May.

Economic development

The Pawnee operate two gaming casinos, three smoke shops, two fuel stations, and one truck stop.[3] Their estimated economic impact for 2010 was $10.5 million. Increased revenues from the casinos have helped them provide for education and welfare of their citizens. They issue their own tribal vehicle tags and operate their housing authority.

Culture

The Pawnee were divided into two large groupings: the Ckiri living in the north and the South Bands (which were further divided into several villages).[4] While the Ckiri were the most populous group of Pawnee, the Cawi of the South Bands were generally the politically leading group, although each band was autonomous. As was typical of many Native American tribes, each band saw to its own. In response to pressures from the Spanish, French and Americans, as well as neighboring tribes, the Pawnee began to draw closer together.

Bands

South Bands

- Cawi,Chaui, Chawi,[1] or Tsawi (‘People in the Middle’, also called "Grand Pawnee")

- Kitkahaki,Kitkehahki, or Kitkehaxki (‘Little Muddy Bottom Village’, often called "Republican Pawnee")

- Pitahawirata or Pitahauirata (‘People Downstream’, ‘Man-Going-East’, derived from Pita - ‘Man’ and Rata - ‘screaming’, the French called them "Tapage Pawnee" - ‘Screaming, Howling Pawnee’, later the Americans "Noisy Pawnee")[5]

- Pitahaureat, Pitahawirata,[1] (Pitahaureat proper, leading group)

- Kawarakis (derived from the Arikara language Kawarusha - ‘Horse’ and Pawnee language Kish - ‘People’, some Pawnee argued that the Kawarakis spoke like the Arikara living to the north, so perhaps they belonged to the refugees (1794–1795) from Lakota aggression, who joined their Caddo kin living south)

Skidi-Federation or Skiri (derived from Tski'ki - ‘Wolf’ or Tskirirara - ‘Wolf-in-Water’, therefore called "Loups", ('Wolves’) by the French and "Wolf Pawnee" by Americans),[6] northernmost band[1]

- Turikaku (‘Center Village’)

- Kitkehaxpakuxtu (‘Old Village’ or ‘Old-Earth-Lodge-Village’)

- Tuhitspiat (‘Village-Stretching-Out-in-the-Bottomlands’)

- Tukitskita (‘Village-on-Branch-of-a-River’)

- Tuhawukasa (‘Village-across-a-Ridge’ or ‘Village-Stretching-across-a-Hill’)

- Arikararikutsu (‘Big-Antlered-Elk-Standing’)

- Arikarariki (‘Small-Antlered-Elk-Standing’)

- Tuhutsaku (‘Village-in-a-Ravine’)

- Tuwarakaku (‘Village-in-Thick-Timber’)

- Akapaxtsawa (‘Buffalo-Skull-Painted-on-Tipi’)

- Tskisarikus (‘Fish-Hawk’)

- Tstikskaatit (‘Black-Ear-of-Corn,’ i.e.‘Corn-black’)

- Turawiu (was only part of a village)

- Pahukstatu (‘Pumpkin-Vine’, did not join the Skidi and remained politically independent, but in general were counted as Skidi)

- Tskirirara (‘Wolf-in-Water’, although the Skidi-Federation got its name from them, they remained politically independent, but were counted within the Pawnee as Skidi)

- Panismaha (also Panimaha, by the 1770s this group of the Skidi Pawnee had broken off and moved toward Texas, where they allied with the Taovaya, the Tonkawa, Yojuane and other Texas tribes)

Villages

The Pawnee had a sedentary lifestyle combining village life and seasonal hunting, which had long been established on the Plains. Archeology studies of ancient sites have demonstrated the people lived in this pattern for nearly 700 years, since about 1250 CE.[7]

The Pawnee generally settled close to the rivers and placed their lodges on the higher banks. They built earth lodges that by historical times tended to be oval in shape; at earlier stages, they were rectangular. They constructed the frame, made of 10–15 posts set some 10 feet (3.0 m) apart, which outlined the central room of the lodge. Lodge size varied based on the number of poles placed in the center of the structure. Most lodges had 4, 8 or 12 center poles. A common feature in Pawnee lodges were four painted poles, which represented the four cardinal directions and the four major star gods (not to be confused with the Creator.) A second outer ring of poles outlined the outer circumference of the lodge. Horizontal beams linked the posts together.

The frame was covered first with smaller poles, tied with willow withes. The structure was covered with thatch, then earth. A hole left in the center of the covering served as a combined chimney/smoke hole and skylight. The door of each lodge was placed to the east and the rising sun. A long, low passageway, which helped keep out outside weather, led to an entry room that had an interior buffalo-skin door on a hinge. It could be closed at night and wedged shut. Opposite the door, on the west side of the central room, a buffalo skull with horns was displayed. This was considered great medicine.

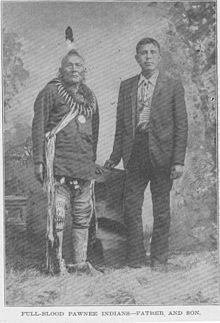

Mats were hung on the perimeter of the main room to shield small rooms in the outer ring, which served as sleeping and private spaces. The lodge was semi-subterranean, as the Pawnee recessed the base by digging it approximately three feet (one meter) below ground level, thereby insulating the interior from extreme temperatures. Lodges were strong enough to support adults, who routinely sat on them, and the children who played on the top of the structures.[8] (See photo above.)

As many as 30–50 people might live in each lodge, and they were usually of related families. A village could consist of as many as 300–500 people and 10–15 households. Each lodge was divided in two (the north and south), and each section had a head who oversaw the daily business. Each section was further subdivided into three duplicate areas, with tasks and responsibilities related to the ages of women and girls, as described below. The membership of the lodge was quite flexible.

The tribe went on buffalo hunts in summer and winter. Upon their return, the inhabitants of a lodge would often move into another lodge, although they generally remained within the village. Men's lives were more transient than those of women. They had obligations of support for the wife (and family they married into), but could always go back to their mother and sisters for a night or two of attention. When young couples married, they lived with the woman's family in a matrilocal pattern.

Political structure

The Pawnee are a matrilineal people. Ancestral descent is traced through the mother, and children are considered born into the mother's clan and are part of her people. Traditionally, a young couple moved into the bride's parents' lodge. People work together in collaborative ways, marked by both independence and cooperation, without coercion. Both women and men are active in political life, with independent decision-making responsibilities.

Within the lodge, each north-south section had areas marked by activities of the three classes of women:

- Mature women (usually married and mothers), who did most of the labor;

- Young single women, just learning their responsibilities; and

- Older women, who looked after the young children.

Among the collection of lodges, the political designations for men were essentially between:

- the Warrior Clique; and

- the Hunting Clique.

Women tended to be responsible for decisions about resource allocation, trade, and inter-lodge social negotiations. Men were responsible for decisions which pertained to hunting, war, and spiritual/health issues.

Women tended to remain within a single lodge, while men would typically move between lodges. They took multiple sexual partners in serially monogamous relationships.

Agriculture

The Pawnee women were skilled horticulturalists and cooks, cultivating and processing ten varieties of corn, seven of pumpkins and squashes, and eight of beans.[9] They planted their crops along the fertile river bottomlands. These crops provided a wide variety of nutrients and complemented each other in making whole proteins. In addition to varieties of flint corn and flour corn for consumption, the women planted an archaic breed which they called "Wonderful" or "Holy Corn", specifically to be included in the sacred bundles.[9]

The holy corn was cultivated and harvested to replace corn in the sacred bundles prepared for the major seasons of winter and summer. Seeds were taken from sacred bundles for the spring planting ritual. The cycle of corn determined the annual agricultural cycle, as it was the first to be planted and first to be harvested (with accompanying ceremonies involving priests and men of the tribe as well.)[9]

In keeping with their cosmology, the Pawnee classified the varieties of corn by color: black, spotted, white, yellow and red (which, excluding spotted, related to the colors associated with the four semi-cardinal directions). The women kept the different strains pure as they cultivated the corn. While important in agriculture, squash and beans were not given the same theological meaning as corn.[9]

Hunting

After they obtained horses, the Pawnee adapted their culture and expanded their buffalo hunting seasons. With horses providing a greater range, the people traveled in both summer and winter westward to the Great Plains for buffalo hunting. They often traveled 500 miles (800 km) or more in a season. In summer the march began at dawn or before, but usually did not last the entire day.

Once buffalo were located, hunting did not begin until the tribal priests considered the time propitious. The hunt began by the men stealthily advancing together toward the buffalo, but no one could kill any buffalo until the warriors of the tribe gave the signal, in order not to startle the animals before the hunters could get in position for the attack on the herd. Anyone who broke ranks could be severely beaten. During the chase, the hunters guided their ponies with their knees and wielded bows and arrows. They could incapacitate buffalo with a single arrow shot into the flank between the lower ribs and the hip. The animal would soon lie down and perhaps bleed out, or the hunters would finish it off. An individual hunter might shoot as many as five buffalo in this way before backtracking and finishing them off. They preferred to kill cows and young bulls, as the taste of older bulls was disagreeable.[10]

After successful kills, the women processed the bison meat, skin and bones for various uses: the flesh was sliced into strips and dried on poles over slow fires before being stored. Prepared in this way, it was usable for several months. Although the Pawnee preferred buffalo, they also hunted other game, including elk, bear, panther, and skunk, for meat and skins. The skins were used for clothing and accessories, storage bags, foot coverings, fastening ropes and ties, etc.

The people returned to their villages to harvest crops when the corn was ripe in late summer, or in the spring when the grass became green and they could plant a new cycle of crops. Summer hunts extended from late June to about the first of September; but might end early if hunting was successful. Sometimes the hunt was limited to what is now western Nebraska. Winter hunts were from late October until early April and were often to the southwest into what is now western Kansas.

Religion

Like many other Native American tribes, the Pawnee had a cosmology with elements of all of nature represented in it. They based many rituals in the four cardinal directions. Pawnee priests conducted ceremonies based on the sacred bundles that included various materials, such as an ear of sacred corn, with great symbolic value. These were used in many religious ceremonies to maintain the balance of nature and the Pawnee relationship with the gods and spirits. The Pawnee were not part of the Sun Dance tradition. In the 1890s, already in Oklahoma, the people participated in the Ghost Dance movement.

The Pawnee believed that the Morning Star and Evening Star gave birth to the first Pawnee woman. The first Pawnee man was the offspring of the union of the Moon and the Sun. As they believed they were descendants of the stars, cosmology had a central role in daily and spiritual life. They planted their crops according to the position of the stars, which related to the appropriate time of season for planting. Like many tribal bands, they sacrificed maize and other crops to the stars.

Morning Star ritual

The Skidi Pawnee practiced human sacrifice, specifically of captive girls, in the "Morning Star ritual". They continued this practice regularly through the 1810s and possibly after 1838, the last reported sacrifice. They believed the longstanding rite ensured the fertility of the soil and success of the crops, as well as renewal of all life in spring. The sacrifice was related to the belief that the first human being was a girl, born of the mating of the Morning Star, the male figure of light, and Evening Star, a female figure of darkness, in their creation story.[11]

Typically, a warrior would dream of the Morning Star, usually in the autumn, which meant it was time to prepare for the various steps of the ritual. The visionary would consult with the Morning Star priest, who helped him prepare for his journey to find a sacrifice. With help from others, the warrior would capture a young unmarried girl from an enemy tribe. The Pawnee kept the girl and cared for her over the winter, taking her with them as they made their buffalo hunt. They arranged her sacrifice in the spring, in relation to the rising of the Morning Star. She was well treated and fed throughout this period.[11]

When the morning star rose ringed with red, the priest knew it was the signal for the sacrifice. He directed the men to carry out the rest of the ritual, including the construction of a scaffold outside the village. It was made of sacred woods and leathers from different animals, each of which had important symbolism. It was erected over a pit with elements corresponding to the four cardinal directions. All the elements of the ritual related to symbolic meaning and belief, and were necessary for the renewal of life. The preparations took four days.[11]

A procession of all the men and boys, even carrying male infants, accompanied the girl out of the village to the scaffold. Together they awaited the morning star. When the star was due to rise, the girl was placed and tied on the scaffold. At the moment the star appeared above the horizon, the girl was shot with an arrow, then the priest cut the skin of her chest to bleed. She was quickly shot with arrows by all the participating men and boys to hasten her death. The girl was carried to the east and placed face down so her blood would soak into the earth, with appropriate prayers for the crops and life she would bring to all life on the prairie.[11]

About 1820–1821, news of these sacrifices reached the East Coast; it caused a sensation among European Americans. Before this, US Indian agents had counseled Pawnee chiefs to suppress the practice, as they warned of how it would upset the American settlers, who were arriving in ever greater number.[citation needed] Knife Chief ransomed at least two captives before sacrifice. For any individual, it was extremely difficult to try to change a practice tied so closely to Pawnee belief in the annual renewal of life for the tribe. In June 1818, the Missouri Gazette of St. Louis contained the account of a sacrifice. The last known sacrifice was of Haxti, a 14-year-old Oglala Lakota girl, on April 22, 1838.[12]

Writing in the 1960s, the historian Gene Weltfish drew from earlier work of Wissler and Spinden to suggest that the sacrificial practice might have been transferred in the early 16th century from the Aztec of present-day Mexico. More recently, historians have disputed the proposed connection to Mesoamerican practice. They believe that the sacrifice ritual originated separately within ancient traditional Pawnee culture.[13]

History

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado visited the neighboring Wichita in 1541 where he encountered a Pawnee chief from Harahey in Nebraska. Nothing much is mentioned of the Pawnee until the 17th and 18th centuries when successive incursions of Spanish, French and English settlers attempted to enlarge their possessions. The tribes tended to make alliances as and when it suited them. Different Pawnee subtribes could make treaties with warring European powers without disrupting their underlying unity; the Pawnee were masters at unity within diversity.

Traditionally Native American and First Nations tribes sold captives from warfare as slaves to other tribes and to European traders. In French Canada, Indian slaves were generally called Panis (anglicized to Pawnee), as most, at first, had been captured from the Pawnee tribe or their relations. Pawnee became synonymous with "Indian slave" in general use in Canada, and a slave from any tribe came to be called Panis. As early as 1670, a historical reference was recorded to a Panis in Montreal.[14] By 1757 Louis Antoine de Bougainville considered that the Panis nation "plays... the same role in America that the Negroes do in Europe."[15] The historian Marcel Trudel documented that close to 2,000 "Panis" slaves lived in Canada until the abolition of slavery in the colony in 1833.[15] Indian slaves comprised close to half of the known slaves in French Canada (also called Lower Canada).

In the 18th century, the Pawnee were allied with the French, with whom they traded. They played an important role in halting Spanish expansion onto the Great Plains by decisively defeating the Villasur expedition in battle in 1720.

A Pawnee tribal delegation visited President Thomas Jefferson. In 1806 Lieutenant Zebulon Pike, Major G. C. Sibley, Major S. H. Long, among others, began visiting the Pawnee villages. Under pressure from Siouan tribes and European-American settlers, the Pawnee ceded territory to the United States government in treaties in 1818, 1825, 1833, 1848, 1857, and 1892. In 1857, they settled on the Pawnee Reservation along the Loup River in present-day Nance County, Nebraska, but maintained their traditional way of life. They were subjected to continual raids by Lakota from the north and west. On one such raid, a Sioux war party of over 1,000 warriors ambushed a Pawnee hunting party of 350 men, women and children. The Pawnee had gained permission to leave the reservation and hunt buffalo. About 70 Pawnee were killed in this attack, which occurred in a canyon in present-day Hitchcock County. The site is known as Massacre Canyon. Because of the ongoing hostilities with the Sioux and encroachment from American settlers to the south and east, the Pawnee decided to leave their Nebraska reservation in the 1870s and settle on a new reservation in Indian Territory, located in what is today Oklahoma.

Until the 1830s, the Pawnee in what became United States territory were relatively isolated from interaction with Europeans. As a result, they were not exposed to Eurasian infectious diseases, such as measles, smallpox, and cholera, to which Native Americans had no immunity.[1] In the 19th century, however, they were pressed by Siouan groups encroaching from the east, who also brought diseases. Epidemics of smallpox and cholera, and endemic warfare with the Sioux and Cheyenne[16] caused dramatic mortality losses among the Pawnee. From an estimated population of 12,000 in the 1830s, they were reduced to 3,400 by 1859, when they were forcibly constrained to a reservation in modern-day Nance County, Nebraska.[17]

The Pawnees in the village of Chief Blue Coat suffered a severe defeat on June 27, 1843. A force of Lakotas attacked the village, killed more than 65 inhabitants and burned 20 earth lodges.[18]

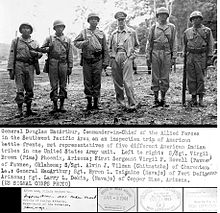

Warriors enlisted as Pawnee Scouts in the latter half of the 19th century in the United States Army. Like other groups of Native American scouts, Pawnee warriors were recruited in large numbers to fight on the Northern and Southern Plains in various conflicts against hostile Native Americans. Because the Pawnee people were old enemies of the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche and Kiowa tribes, they served with the army for fourteen years between 1864 and 1877, earning a reputation as being a well-trained unit, especially in tracking and reconnaissance. The Pawnee Scouts took part with distinction in the Battle of the Tongue River during the Powder River Expedition (1865) against Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho and in the Battle of Summit Springs. They also fought with the US in the Great Sioux War of 1876. On the Southern Plains they fought against their old enemies, the Comanches and Kiowa, in the Comanche Campaign.

In 1874, the Pawnee requested relocation to Indian Territory (Oklahoma), but the stress of the move, diseases and poor conditions on their reservation reduced their numbers even more. During this time, outlaws often smuggled whiskey to the Pawnee. The teenaged female bandits Little Britches and Cattle Annie were imprisoned for this crime.[19]

In 1875 most members of the nation moved to Indian Territory, a large area reserved to receive tribes displaced from east of the Mississippi River and elsewhere. The warriors resisted the loss of their freedom and culture, but gradually adapted to reservations. On November 23, 1892, the Pawnee in Oklahoma signed an agreement with the Cherokee Commission to accept individual allotments of land in a breakup of their communal holding.[20]

By 1900, the Pawnee population was recorded by the US Census as 633. Since then the tribe has begun to recover in numbers.[21]

Recent history

In 1906, in preparation for statehood of Oklahoma, the US government dismantled the Pawnee tribal government and civic institutions. The tribe reorganized under the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936 and established the Pawnee Business Council, the Nasharo (Chiefs) Council, and a tribal constitution, bylaws, and charter.[1]

In the 1960s, the government settled a suit by the Pawnee Nation regarding their compensation for lands ceded to the US government in the 19th century. By an out-of-court settlement in 1964, the Pawnee Nation was awarded $7,316,097 for land ceded to the US and undervalued by the federal government in the previous century.[22]

Bills such as the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 have allowed the Pawnee Nation to regain some of its self-government. The Pawnee continue to practice cultural traditions, meeting twice a year for the intertribal gathering with their kinsmen the Wichita Indians. They have an annual four-day Pawnee Homecoming for Pawnee veterans in July. Many Pawnee also return to their traditional lands to visit relatives and take part in scheduled powwows.

Notable Pawnee

- Acee Blue Eagle, artist and educator

- Big Spotted Horse, 19th-century warrior and raider

- John EchoHawk, lawyer and founder of the Native American Rights Fund, older cousin of Walter Echo-Hawk (below)[23]

- Larry Echo Hawk, Bureau of Indian Affairs Director.[24] He was elected Attorney General of Idaho (1991–1995).

- Walter Echo-Hawk, senior attorney at NARF, worked on major 20th-century legislation for Native American rights, such as the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act[23]

- Kevin Gover, director of the National Museum of the American Indian.

- Moses J. "Chief" Yellow Horse, Major League Baseball player

- Old Lady Grieves The Enemy, 19th-century woman warrior

- Petalesharo, a Skidi Pawnee chief who in 1817 rescued an Ietan Comanche girl from Pawnee ritual human sacrifice.

- Anna Lee Walters (b. 1946), Otoe-Missouria-Pawnee author and educator

- Wicked Chief, visited President James Monroe in 1822 with a delegation of Native American dignitaries.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Parks, Douglas R. "Pawnee." Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. (retrieved 14 Sept 2011)

- ^ Viola, Herman J. "Warriors in Uniform: The Legacy of American Indian Heroism". National Geographic Books. p. 101. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ a b 2013 Pawnee Nation annual report Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. 20>Parks, Douglas R. "Pawnee." Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. (retrieved 14 Sept 2011)

- ^ Weltfish 5

- ^ Hyde 361

- ^ Weltfish 463

- ^ Weltfish 4–8

- ^ Carleton, James Henry (1983). The Prairie Logbooks. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 66–68. ISBN 0-8032-6314-7.

- ^ a b c d Weltfish 119–122

- ^ W.P. Clark, "Hunt", The Indian Sign Language, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press (1982, first published 1885), trade paperback, 444 pages, ISBN 0-8032-6309-0

- ^ a b c d Weltfish 106-118

- ^ Weltfish 117

- ^ Philip Duke, "THE MORNING STAR CEREMONY OF THE SKIRI PAWNEE AS DESCRIBED BY ALFRED C. HADDON"], The Plains Anthropologist, Vol. 34, No. 125 (August 1989), pp. 193-203

- ^ Carter Godwin Woodson, "The Slave in Canada", The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 5, July 1920, No. 3, pp. 263-264. Retrieved 17 November 2009

- ^ a b Canada's Forgotten Slaves. Marcel Trudel with Micheline D'Allaire. 1963. Translated by George Tombs 2013. Véhicule Press p.64

- ^ Hyde 85–336

- ^ "History of Nance County, Nebraska, NEGenWeb Project". Usgennet.org.

- ^ Letters Concerning the Presbyterian Mission in the Pawnee Country, near Bellevue, Nebraska, 1831-1849. Kansas Historical Collections, Vol. 14 (1915-1919), p. 730.

- ^ "Cattle Annie & Little Britches, taken from Lee Paul [http://www.theoutlaws.com]". ranchdivaoutfitters.com. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ Deloria Jr., Vine J; DeMaille, Raymond J (1999). Documents of American Indian Diplomacy Treaties, Agreements, and Conventions, 1775-1979. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 361–363. ISBN 978-0-8061-3118-4.

- ^ Weltfish 3-4

- ^ 78 Stat. 585 (1964); Wishart, David J., 1985. "The Pawnee Claims Case, 1947–64," Irredeemable America: The Indians' Estate and Land Claims, ed. I. Sutton (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press): 157–186.

- ^ a b The New Warriors: Native American Leaders Since 1900, edited by R. David Edmunds, University of Nebraska Press, 2004, pp. 299-322

- ^ "Nominee Named for Indian Affairs", Associated Press, New York Times, 10 April 2009

References

- Hyde, George E. The Pawnee Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1974. ISBN 0-8061-2094-0.

- Weltfish, Gene. The Lost Universe, Pawnee Life and Culture. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8032-5871-2.

- Blaine, Martha R. Pawnee Passage 1870-1875, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8061-2300-1.

- Blaine, Martha R. The Pawnee: A Critical Bibliography, 1980 Newberry Library, Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-02533-1502-1

Further reading

- Robert O. Lagace, "Pawnee: Culture summary", Ethnographic Atlas, University of Kent, Canterbury.

- Howard Meredith, Dancing on Common Ground: Tribal Cultures and Alliances on the Southern Plains, Lawrence: University of Kansas, 1995 - addresses achieving and maintaining peace among the Wichita, Pawnee, Caddo, Plains Apache, Cheyenne and Arapaho, and Comanche.

- "Pawnee", Encyclopedia of North American Indians, New York: Houghton Mifflin

- J. S. Clark, "A Pawnee Buffalo Hunt", Oklahoma Chronicles, Volume 20, No. 4, December 1942, Oklahoma State Historical Society

- Blaine, Martha R. Some Things Are Not Forgotten: A Pawnee Family Remembers, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8032-1275-5

External links

- Pawnee Nation, official website

- Pawnee Indian Tribe, Access Genealogy

- Pawnee Indian History in Kansas

- Pawnee Indians - Their Lands, Allies and Enemies

- Pawnee Indian Village Museum, A museum featuring the excavated floor of a large 1820s Pawnee earth lodge and associated artifacts, Kansas State Historical Society

- "Kansas Monument Site", Archaeophysics, describes technique and findings of non-invasive imagery of a Pawnee 18th–19th-century archaeological site located on the Republican River.

- Inventory of the Gene Weltfish Pawnee Field Notes, 1935, Newberry Library