Prehistory: Difference between revisions

Doug Weller (talk | contribs) Reverted to revision 572509791 by Treisijs: rvv. (TW) |

|||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

|{{Human history and prehistory}} |

|{{Human history and prehistory}} |

||

|} |

|} |

||

''' |

'''Prehihi hi '''''præ'') is the span of time before [[recorded history]] or the invention of [[writing systems]]. Prehistory can refer to the period of human existence before the availability of those written records with which recorded history begins.<ref>Renfrew, Colin. Prehistory The Making Of The Human Mind. New York: Modern Library,2008. Print.</ref> More broadly, it refers to all the time preceding human existence and the invention of writing. Archaeologist Paul Tournal originally coined the term ''anté-historique''<ref>pre-historic (french)</ref> in describing the finds he had made in the caves of [[southern France]].<ref>Bruno David, Bryce Barker, Ian J. McNiven (2006). The social archaeology of Australian indigenous societies. Page 55. (cf. "A parallel term anté-historique had earlier been coined by Paul Tournal.")</ref> Thus, the term came into use in France in the 1830s to describe the time before writing, and the word "prehistoric" was later introduced into [[English language|English]] by archaeologist [[Daniel Wilson (academic)|Daniel Wilson]] in 1851.<ref |

||

name="Simpson">{{cite web |

name="Simpson">{{cite web |

||

|url=http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/PSAS_2002/pdf/vol_096/96_001_008.pdf |

|url=http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/PSAS_2002/pdf/vol_096/96_001_008.pdf |

||

Revision as of 17:51, 16 September 2013

| |||||||

|

Prehihi hi præ) is the span of time before recorded history or the invention of writing systems. Prehistory can refer to the period of human existence before the availability of those written records with which recorded history begins.[1] More broadly, it refers to all the time preceding human existence and the invention of writing. Archaeologist Paul Tournal originally coined the term anté-historique[2] in describing the finds he had made in the caves of southern France.[3] Thus, the term came into use in France in the 1830s to describe the time before writing, and the word "prehistoric" was later introduced into English by archaeologist Daniel Wilson in 1851.[4][5]

The term "prehistory" can refer to the vast span of time since the beginning of the Universe, but more often it refers to the period since life appeared on Earth, or even more specifically to the time since human-like beings appeared.[6][7] In dividing up human prehistory, prehistorians typically use the three-age system, whereas scholars of pre-human time periods typically use the well defined geologic record and its internationally defined stratum base within the geologic time scale. The three-age system is the periodization of human prehistory into three consecutive time periods, named for their respective predominant tool-making technologies: the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age. Another division of history and prehistory can be made between those written events that can be precisely dated by use of a continuous calendar dating from current and those that can't. The loss of continuity of calendar date most often occurs when a civilization falls and the language and calendar fall into disuse. The current civilization therefore loses the ability to precisely date events written through primary sources to events dated to current calendar dating.

The occurrence of written materials (and so the beginning of local "historic times") varies generally to cultures classified within either the late Bronze Age or within the Iron Age. Historians increasingly do not restrict themselves to evidence from written records and are coming to rely more upon evidence from the natural and social sciences, thereby blurring the distinction between the terms "history" and "prehistory".[8][9][10] This view has recently[when?] been articulated by advocates of deep history.

This article is primarily concerned with human prehistory, or the time since behaviorally and anatomically modern humans first appear until the beginning of recorded history. There are separate articles for the overall history of the Earth and the history of life before humans.

Definition

Because, by definition, there are no written records from human prehistory, dating of prehistoric materials is particularly crucial to the enterprise. Clear techniques for dating were not well-developed until the 19th century.[11]

The primary researchers into human prehistory are prehistoric archaeologists and physical anthropologists who use excavation, geologic and geographic surveys, and other scientific analysis to reveal and interpret the nature and behavior of pre-literate and non-literate peoples.[6] Human population geneticists and historical linguists are also providing valuable insight for these questions.[7] Cultural anthropologists help provide context for societal interactions, by which objects of human origin pass among people, allowing an analysis of any article that arises in a human prehistoric context.[7] Therefore, data about prehistory is provided by a wide variety of natural and social sciences, such as paleontology, biology, archaeology, palynology, geology, archaeoastronomy, comparative linguistics, anthropology, molecular genetics and many others.

Prehistory is an important part of evolutionary psychology since it is argued that many human characteristics are adaptations to the prehistoric environment and in particular the environment during the long paleolithic period.[12]

Human prehistory differs from history not only in terms of its chronology but in the way it deals with the activities of archaeological cultures rather than named nations or individuals. Restricted to material processes, remains and artifacts rather than written records, prehistory is anonymous. Because of this, reference terms that prehistorians use, such as Neanderthal or Iron Age are modern labels with definitions sometimes subject to debate.

The date marking the end of prehistory in a particular culture or region, that is, the date when relevant written historical records become a useful academic resource, varies enormously from region to region. For example, in Egypt it is generally accepted that prehistory ended around 3200 BCE, whereas in New Guinea the end of the prehistoric era is set much more recently, at around 1900 CE. In Europe the relatively well-documented classical cultures of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome had neighbouring cultures, including the Celts, and to a lesser extent the Etruscans, with little or no writing, and historians must decide how much weight to give to the often highly prejudiced accounts of these "prehistoric" cultures in Greek and Roman literature.

Stone Age

Paleolithic

"Paleolithic" means "Old Stone Age," and begins with the first use of stone tools. The Paleolithic is the earliest period of the Stone Age.

The early part of the Paleolithic is called the Lower Paleolithic, which predates Homo sapiens, beginning with Homo habilis (and related species) and with the earliest stone tools, dated to around 2.5 million years ago.[13] Early homo sapiens originated some 200,000 years ago, ushering in the Middle Paleolithic. Anatomic changes indicating modern language capacity also arise during the Middle Paleolithic.[14] The systematic burial of the dead, the music, early art, and the use of increasingly sophisticated multi-part tools are highlights of the Middle Paleolithic.

Throughout the Paleolithic, humans generally lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers. Hunter-gatherer societies tended to be very small and egalitarian,[15] though hunter-gatherer societies with abundant resources or advanced food-storage techniques sometimes developed sedentary lifestyles with complex social structures such as chiefdoms, and social stratification. Long-distance contacts may have been established, as in the case of Indigenous Australian "highways."

Mesolithic

The "Mesolithic," or "Middle Stone Age" (from the Greek "mesos," "middle," and "lithos," "stone") was the period in the development of human technology between the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods of the Stone Age.

The Mesolithic period began at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, some 10,000 BP, and ended with the introduction of agriculture, the date of which varied by geographic region. In some areas, such as the Near East, agriculture was already underway by the end of the Pleistocene, and there the Mesolithic is short and poorly defined. In areas with limited glacial impact, the term "Epipaleolithic" is sometimes preferred.

Regions that experienced greater environmental effects as the last ice age ended have a much more evident Mesolithic era, lasting millennia. In Northern Europe, societies were able to live well on rich food supplies from the marshlands fostered by the warmer climate. Such conditions produced distinctive human behaviours that are preserved in the material record, such as the Maglemosian and Azilian cultures. These conditions also delayed the coming of the Neolithic until as late as 4000 BCE (6,000 BP) in northern Europe.

Remains from this period are few and far between, often limited to middens. In forested areas, the first signs of deforestation have been found, although this would only begin in earnest during the Neolithic, when more space was needed for agriculture.

The Mesolithic is characterized in most areas by small composite flint tools — microliths and microburins. Fishing tackle, stone adzes and wooden objects, e.g. canoes and bows, have been found at some sites. These technologies first occur in Africa, associated with the Azilian cultures, before spreading to Europe through the Ibero-Maurusian culture of Northern Africa and the Kebaran culture of the Levant. Independent discovery is not always ruled out.

Neolithic

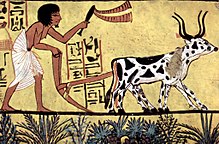

"Neolithic" means "New Stone Age." This was a period of primitive technological and social development, toward the end of the "Stone Age". The Neolithic period saw the development of early villages, agriculture, animal domestication, tools and the onset of the earliest recorded incidents of warfare.[17] The Neolithic term is commonly used in the Old World, as its application to cultures in the Americas and Oceania that did not fully develop metal-working technology raises problems.

Agriculture

Forest gardening, originating in prehistory, is thought to be the world's oldest known form of agriculture (or agroecosystem).[18] Vere Gordon Childe then describes an "Agricultural Revolution" occurring about the 10th millennium BCE with the adoption of agriculture and domestication of plants and animals. The Sumerians first began farming c. 9500 BCE. By 7000 BCE, agriculture had been developed in India and Peru separately; by 6000 BCE, in Egypt; by 5000 BCE, in China. About 2700 BCE, agriculture had come to Mesoamerica.

Although attention has tended to concentrate on the Middle East's Fertile Crescent, archaeology in the Americas, East Asia and Southeast Asia indicates that agricultural systems, using different crops and animals, may in some cases have developed there nearly as early. The development of organised irrigation, and the use of a specialised workforce, by the Sumerians, began about 5500 BCE. Stone was supplanted by bronze and iron in implements of agriculture and warfare. Agricultural settlements had until then been almost completely dependent on stone tools. In Eurasia, copper and bronze tools, decorations and weapons began to be commonplace about 3000 BCE. After bronze, the Eastern Mediterranean region, Middle East and China saw the introduction of iron tools and weapons.

The Americas developed metallurgy for decorative objects, but did not use metal extensively for utilitarian purposes. No evidence of melting, smelting, or casting has been found in the prehistoric Americas. However, little archaeological research has so far been done in Peru, and nearly all the khipus (recording devices, in the form of knots, used by the Incas) were burned in the Spanish conquest of Peru. As late as 2004, entire cities were still being unearthed.

The cradles of early civilizations were river valleys, such as the Euphrates and Tigris valleys in Mesopotamia, the Nile valley in Egypt, the Indus valley in the Indian subcontinent, and the Yangtze and Yellow River valleys in China. Some nomadic peoples, such as the Indigenous Australians and the Bushmen of southern Africa, did not practice agriculture until relatively recent times.

Agriculture made possible complex societies — civilizations. States and markets emerged. Technologies enhanced people's ability to harness nature and to develop transport and communication."The city represented a new degree of human concentration, a new magnitude in settlement".[19] Cities relied on agricultural surplus."since the inhabitants of a city do not produce their own food...cities cannot support themselves...thus exist only where agriculture is successful enough to produce agricultural surplus." [20]

Chalcolithic

In Old World archaeology, the "Chalcolithic", "Eneolithic" or "Copper Age" refers to a transitional period where early copper metallurgy appeared alongside the widespread use of stone tools.

Bronze Age

The term Bronze Age refers to a period in human cultural development when the most advanced metalworking (at least in systematic and widespread use) included techniques for smelting copper and tin from naturally occurring outcroppings of ores, and then combining them to cast bronze. These naturally occurring ores typically included arsenic as a common impurity. Copper/tin ores are rare, as reflected in the fact that there were no tin bronzes in Western Asia before 3000 BCE. The Bronze Age forms part of the three-age system for prehistoric societies. In this system, it follows the Neolithic in some areas of the world.

The Bronze Age is the earliest period for which we have direct written accounts, since the invention of writing coincides with its early beginnings.[citation needed]

Iron Age

In archaeology, the Iron Age refers to the advent of ferrous metallurgy. The adoption of iron coincided with other changes in some past cultures, often including more sophisticated agricultural practices, religious beliefs and artistic styles, which makes the archaeological Iron Age coincide with the "Axial Age" in the history of philosophy.

Timeline

All dates are approximate and conjectural, obtained through research in the fields of anthropology, archaeology, genetics, geology, or linguistics. They are all subject to revision due to new discoveries or improved calculations. BP stands for "Before Present (1950)."

- c. 2.5 million BP - Evidence of early human tools

- c. 2.4 million BP - Genus Homo appears as a carnivorous scavenger

- c. 600,000 BP - Hunting-gathering

- c. 400,000 BP Control of fire by early humans

- c. 200,000 BP - Anatomically modern Homo sapiens appear in Africa, including by this point lack of significant hair compared to other primates

- c. 300,000 BP to 30,000 BP. Mousterian (Neanderthal) culture in Europe.[21]

- c. 75,000 BP - Toba Volcano supereruption.[22]

- c. 70,000 - 50,000 BP - Homo sapiens move from Africa to Asia.[23] In the next millennia, these human groups' descendants move on to southern India, the Malay islands, Australia, Japan, China, Siberia, Alaska, and the northwestern coast of North America.[23]

- c. 50,000? BP - Behavioral modernity, by this point including language and sophisticated cognition

- c. 42,000 - 650,000? BP - Invention of clothing

- c. 32,000 BP - Aurignacian culture begins in Europe.

- c. 30,000 BP / 28,000 BCE - A herd of reindeer is slaughtered and butchered by humans in the Vezere Valley in what is today France.[24]

- c. 28,500 BCE - New Guinea is populated by colonists from Asia or Australia.[25]

- c. 28,000 BP - 20,000 BP - Gravettian period in Europe. Harpoons, needles, and saws invented.

- c. 26,000 BP / c. 24,000 BCE - Women around the world use fibers to make baby-carriers, clothes, bags, baskets, and nets.

- c. 25,000 BP / 23,000 BCE - A hamlet consisting of huts built of rocks and of mammoth bones is founded in what is now Dolni Vestonice in Moravia in the Czech Republic. This is the oldest human permanent settlement that has yet been found by archaeologists.[26]

- c. 20,000 BP or 18,000 BCE - Chatelperronian culture in France.[27]

- c. 16,000 BP / 14,000 BCE - Wisent sculpted in clay deep inside the cave now known as Le Tuc d'Audoubert in the French Pyrenees near what is now the border of Spain.[28]

- c. 14,800 BP / 12,800 BCE - The Humid Period begins in North Africa. The region that would later become the Sahara is wet and fertile, and the Aquifers are full.[29]

- c. 8000 BCE / 7000 BCE - In northern Mesopotamia, now northern Iraq, cultivation of barley and wheat begins. At first they are used for beer, gruel, and soup, eventually for bread.[30] In early agriculture at this time, the Planting stick is used, but it is replaced by a primitive Plow in subsequent centuries.[31] Around this time, a round stone tower, now preserved to about 8.5 meters high and 8.5 meters in diameter is built in Jericho.[32]

- c. 3700 BCE - Cuneiform writing appears in Sumer, and records begin to be kept. According to the majority of specialists, the first Mesopotamian writing was a tool that had little connection to the spoken language.[33]

- c. 3000 BCE - Stonehenge construction begins. In its first version, it consisted of a circular ditch and bank, with 56 wooden posts.[34]

By region

- Old World

- Prehistoric Africa

- Prehistoric Asia

- East Asia:

- South Asia

- Prehistory of Central Asia

- Prehistoric Siberia

- Southwest Asia (Near East)

- Prehistoric Europe

- New World

See also

- Archaeoastronomy

- Archaeology

- Paleoanthropology

- Prehistoric migration

- Archaic Homo sapiens

- Behavioral modernity

- Prehistoric art

- Prehistoric religion

- Prehistoric music

- Prehistoric warfare

- Prehistoric medicine

- Periodization

- Synoptic table of the principal old world prehistoric cultures

- Three-age system

- Holocene

- Younger Dryas

- Band society

- Lineage-bonded society

- Pantribal sodalities

- History of the family

- Human evolution

References

- ^ Renfrew, Colin. Prehistory The Making Of The Human Mind. New York: Modern Library,2008. Print.

- ^ pre-historic (french)

- ^ Bruno David, Bryce Barker, Ian J. McNiven (2006). The social archaeology of Australian indigenous societies. Page 55. (cf. "A parallel term anté-historique had earlier been coined by Paul Tournal.")

- ^ Simpson, Douglas (1963-11-30). "Sir Daniel Wilson and the Prehistoric Annals of Scotland, A Centennial Study" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society, 1963-1964. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ^ Wilson, Daniel (1851). The archaeology and prehistoric annals of Scotland. p. xiv.

- ^ a b Fagan, Brian. 2007. World Prehistory: A brief introduction New York:Prentice-Hall, Seventh Edition, Chapter One

- ^ a b c Renfrew, Colin. 2008. Prehistory: The Making of the Human Mind." New York: Modern Library

- ^ The Prehistory of Iberia: Debating Early Social Stratification and the State edited by María Cruz Berrocal, Leonardo García Sanjuán, Antonio Gilman. Pg 36.

- ^ Historical Archaeology: Back from the Edge. Edited by Pedro Paulo A. Funari, Martin Hall, Sian Jones. Pg 8.

- ^ Through the Ages in Palestinian Archaeology: An Introductory Handbook. By Walter E. Ras. Pg 49.

- ^ Graslund, Bo. 1987. The birth of prehistoric chronology. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

- ^ The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (2005), David M. Buss, Chapter 1, pp. 5-67, Conceptual Foundations of Evolutionary Psychology, John Tooby and Leda Cosmides

- ^ The Essence of Anthropology 3rd ed. By William A. Haviland, Harald E. L. Prins, Dana Walrath, Bunny McBrid. Pg 83.

- ^ Race and Human Evolution. By Milford H. Wolpoff. Pg 348.

- ^ Vanishing Voices : The Extinction of the World's Languages. By Daniel Nettle, Suzanne Romaine Merton Professor of English Language University of Oxford. Pg 102-103.

- ^ http://www.heritagemalta.org/hagarqim.html

- ^ The Perfect Gift: Prehistoric Massacres. The twin vices of women and cattle in prehistoric Europe

- ^ Douglas John McConnell (2003). The Forest Farms of Kandy: And Other Gardens of Complete Design. p. 1. ISBN 9780754609582.

- ^ Mumford, Lewis. The City In History Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects. New York: A Harvest Book Harcourt, Inc, 1961. Print.

- ^ Ziomkowski, Robert. The Best Test Preparation for the Western Civilization. New Jersey: Research & Educational Association, 2006. E book.

- ^ Shea, J. J. 2003. Neanderthals, competition and the origin of modern human behaviour in the Levant. Evolutionary Anthropology 12: 173-187.

- ^ "Mount Toba Eruption - Ancient Humans Unscathed, Study Claims". Retrieved 2008-04-20.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b This is indicated by the M130 marker in the Y chromosome. "Traces of a Distant Past," by Gary Stix, Scientific American, July 2008, pages 56-63.

- ^ Gene S. Stuart, "Ice Age Hunters: Artists in Hidden Cages." In Mysteries of the Ancient World, a publication of the National Geographic Society, 1979. Pages 11-18.

- ^ James Trager, The People's Chronology, 1994, ISBN 0-8050-3134-0

- ^ Stuart, Gene S. (1979). "Ice Age Hunters: Artists in Hidden Cages". Mysteries of the Ancient World. National Geographic Society. p. 19.

- ^ Encyclopedia Americana, 2003 edition, volume 6, page 334.

- ^ Stuart, Gene S. (1979). "Ice Age Hunters: Artists in Hidden Cages". Mysteries of the Ancient World. National Geographic Society. pp. 8–10.

- ^ "Shift from Savannah to Sahara was Gradual," by Kenneth Chang, New York Times, May 9, 2008.

- ^ Kiple, Kenneth F. and Ornelas, Kriemhild Coneè, eds., The Cambridge World History of Food, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 83

- ^ "No-Till: The Quiet Revolution," by David Huggins and John Reganold, Scientific American, July 2008, pages 70-77.

- ^ Fagan, Brian M, ed. The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1996 ISBN 978-0-521-40216-3 p 363

- ^ Glassner, Jean-Jacques. The Invention of Cuneiform: Writing In Sumer. Trans.Zainab,Bahrani. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. Ebook.

- ^ Caroline Alexander, "Stonehenge," National Geographic, June 2008.

External links

- Submerged Landscapes Archaeological Network

- The Neanderthal site at Veldwezelt-Hezerwater, Belgium.

- North Pacific Prehistory is an academic journal specialising in Northeast Asian and North American archaeology.

- Prehistory in Algeria and in Morocco [1]

- Early Humans a collection of resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library.