Proso millet

| Proso millet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ripe proso millet | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. miliaceum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Panicum miliaceum | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

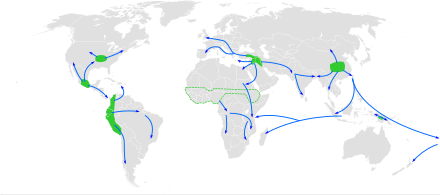

Panicum miliaceum with many common names including proso millet,[2] broomcorn millet,[3] common millet,[2] broomtail millet,[4] hog millet,[2] red millet,[2] and white millet,[2] is a grass species used as a crop. Both the wild ancestor and location of the original domestication of proso millet are unknown, but it first appears as a crop in both Transcaucasia and China about 7,000 years ago, suggesting it may have been domesticated independently in each area. It is still extensively cultivated in India, Nepal, Russia, Ukraine, the Middle East, Turkey and Romania. In the United States, proso is mainly grown for birdseed. It is sold as health food, and due to its lack of gluten, it can be included in the diets of people who cannot tolerate wheat.

The name comes from the pan-Slavic general and generic name for millet (Russian, Serbian, Macedonian, Template:Lang-bg and Polish, Czech, Slovakian, Slovenian, Template:Lang-hr).

Proso is well adapted to many soil and climatic conditions; it has a short growing season, and needs little water. The water requirement of proso is probably the lowest of any major cereal. It is an excellent crop for dryland and no-till farming. Proso millet is an annual grass whose plants reach an average height of 100 cm (4 feet.). Like corn, it has a C4 photosynthesis. The seedheads grow in bunches. The seeds are small (2–3 mm or 0.1 inch) and can be cream, yellow, orange-red, or brown in colour.

Proso is an annual grass like all other millets, but it is not closely related to pearl millet, foxtail millet, finger millet, or the barnyard millets.

History and domestication

Unlike the foxtail millet, the wild ancestor of the proso millet has not yet been satisfactorily identified. Weedy forms of this grain are found in central Asia, covering a widespread area from the Caspian Sea east to Xinjiang and Mongolia, and it may be that these semiarid areas harbor "genuinely wild P. miliaceum forms."[6] This millet has been reportedly found in Neolithic sites in Georgia (dated to the fifth and fourth millennia BC), in Germany (near Leipzig, Hadersleben) by Linear Pottery culture (Early LBK, Neolithikum 5500–4900 BCE),[7] as well as excavated Yangshao culture farming villages east in China.

Proso millet appears to have reached Europe not long after its appearance in Georgia, first appearing in east and central Europe; however, the grain needed a few thousand more years to cross into Italy, Greece, and Iran, and the earliest evidence for its cultivation in the Near East is a find in the ruins of Nimrud, Iraq dated to about 700 BC.[8]

While proso millet is not a member of the Neolithic Near East crop assemblage, it arrived in Europe no later than the time these introductions did, and proso millet as an independent domestication could predate the arrival of the Near East grain crops.[8]

Cultivation

Proso millet is a relatively low-demanding crop and diseases are not known; consequently, proso millet is often used in organic farming systems in Europe. In the United States it is often used as an intercrop. Thus, proso millet can help to avoid a summer fallow, and continuous crop rotation can be achieved. Its superficial root system and its resistance to atrazine residue make proso millet a good intercrop between two water- and pesticide-demanding crops. The stubbles of the last crop, by allowing more heat into the soil, result in a faster and earlier millet growth. While millet occupies the ground, because of its superficial root system, the soil can replenish its water content for the next crop. Later crops, for example, a winter wheat, can in turn benefit from the millet stubble, which act as snow accumulators.[9]

Climate and soil requirements

Due to its C4 photosynthetic system, proso millet is thermophilic like maize. Therefore, shady locations of the field should be avoided. It is sensitive to cold temperatures lower than 10 to 13 degrees Celsius. Proso millet is highly drought-resistant, which makes it of interest to regions with low water availability and longer periods without rain.[10][11] The soil should be light or medium-heavy. Due to its flat root systems, soil compaction must be avoided. Furthermore, proso millet does not tolerate soil wetness caused by dammed-up water.[11]

Seedbed and sowing

The seedbed should be finely crumbled as for sugar beet and rapeseed.[10] In Europe proso millet is sowed between mid-April and the end of May. 500g/are of seeds are required which comes up to 500 grains/m2. In organic farming this amount should be increased if a harrow weeder is used. For sowing, the usual sowing machines can be used similarly to how they are used for other crops like wheat. A distance between the rows of from 16 to 25 centimeters is recommended if the farmer uses an interrow cultivator. The sowing depth should be 1.5 up to 2 cm in optimal soil or 3 to 4 cm in dry soil. Rolling of the ground after sowing is helpful for further cultivation.[10] Cultivation in no-till farming systems is also possible and often practiced in the United States. Sowing then can be done two weeks later.[9]

Field management

Only a few diseases and pests are known to attack proso millet, but they are not economically important. Weeds are a bigger problem. The critical phase is in juvenile development. The formation of the grains happens in the 3, up to 5, leaf stadium. After that, all nutrients should be available for the millet, so it is necessary to prevent the growth of weeds. In conventional farming, herbicides may be used. In organic farming it is possible to use harrow weeders and interrow cultivators, but special sowing parameters described in the chapter above are needed.[10] For good crop development, fertilization with 50 to 75 kg nitrogen per hectare is recommended.[11] Planting proso millet in a crop rotation after maize should be avoided due to its same weed spectrum. Because proso millet is an undemanding crop, it may be used at the end of the rotation.[10]

Harvesting and post-harvest treatments

Harvest time is at the end of August until mid-September. Determining the best harvest date is not easy because all the grains do not ripen simultaneously. The grains on the top of the panicle ripen first while the grains in the lower parts need more time, making it necessary to compromise and harvest when the yield is highest.[10] Harvesting can be done with a conventional combine harvester with moisture content of the grains at about 15-20%. Usually proso millet is mowed at windrows first since the plants are not dry like wheat. There they can wither, which makes the threshing easier. Then the harvest is done with a pickup truck attached to a combine.[10] Possible yields are between 2.5 and 4.5 tons per hectare under optimal conditions. Studies in Germany showed that even higher yields can be attained.[10]

Uses

Proso millet is one of the few types of millet not cultivated in Africa.[12] In the United States, former Soviet Union, and some South American countries, it is primarily grown for livestock feed. As a grain fodder, it is very deficient in lysine and needs complementation. Proso millet is also a poor fodder due to its low leaf:stem ratio and a possible irritant effect due to its hairy stem. Foxtail millet, having a higher leaf:stem ratio and less hairy stems, is preferred as fodder, particularly the variety called moha, which is a high-quality fodder.

In order to promote millet cultivation, other potential uses have been considered recently.[13] For example, starch derived from millets has been shown to be a good substrate for fermentation and malting with grains having similar starch contents as wheat grains.[13] A recently published study suggested that starch derived from proso millet can be converted to ethanol with an only moderately lower efficiency than starch derived from corn.[14] The development of varieties with highly fermentable characteristics could improve ethanol yield to that of highly fermentable corn.[14] Since proso millet is compatible with low-input agriculture, cultivation on marginal soils for biofuel production could represent an important new market, such as for farmers in the High Plains of the US.[14] The demand for more diverse and healthier cereal-based foods is increasing, particularly in affluent countries.[15] This could create new markets for proso millet products in human nutrition. Protein content in proso millet grains is comparable with that of wheat, but the share of essential amino acids (leucine, isoleucine and methionine) is substantially higher in proso millet.[15] In addition, health-promoting phenolic compounds contained in the grains are readily bioaccessible and their high calcium content favor bone strengthening and dental health.[15] Among the most commonly consumed products are ready-to-eat breakfast cereals made purely from millet flour [10][15] as well as a variety of noodles and bakery products, which are, however, often produced from mixtures with wheat flour to improve their sensory quality.[15]

References

- ^ "The Plant List: A Working List of All Plant Species". Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "USDA GRIN Taxonomy". Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/taxon.pl?317710

- ^ Li, L.M. (2007). Fighting Famine in North China: State, Market, and Environmental Decline, 1690s-1990s. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804753043.

- ^ Diamond, J.; Bellwood, P. (2003). "Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions". Science. 300 (5619): 597–603. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..597D. doi:10.1126/science.1078208. PMID 12714734.

- ^ Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, Domestication of plants in the Old World, third edition (Oxford: University Press, 2000), p. 83

- ^ Udelgard Körber-Grohne: Nutzpflanzen in Deutschland: Kulturgeschichte und Biologie, Verlag Theiss, 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0481-0

- ^ a b Zohary and Hopf, Domestication, p. 86

- ^ a b Producing and marketing proso millet in the great plains, U. Nabraska-Lincoln Extension

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Merkblatt für den Anbau von Rispenhirse im biologischen Landbau, www.biofarm.ch, http://www.biofarm.ch/assets/files/Landwirtschaft/Merkblatt_Biohirse_Version%2012_2010.pdf (23.11.14)

- ^ a b c Pearl Millet and Other Millets, Wayne W. Hanna, David D. Baltensperger, Annadana Seetharam (2004)

- ^ National Research Council (1996-02-14). "Ebony". Lost Crops of Africa: Volume I: Grains. Lost Crops of Africa. Vol. 1. National Academies Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-309-04990-0. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Rose, D.J., Santra, D.K., 2013. Proso millet (Panicum miliaceum L.) fermentation for fuel ethanol production. Industrial Crops and Products 43, p. 602-605.

- ^ a b c Taylor, J.R.N., Schober, T.J., Bean, S.R., 2006. Novel food an non-food uses for sorghum and millets. Journal of Ceral Science 44, p. 252-271.

- ^ a b c d e Saleh, A.S.M., Zhang, Q., Chen, J., Shen, Q., 2012. Millet Grains: Nutritional Quality, Processing, and Potential Health Benefits. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 12, p. 281-295.

External links

Media related to Millet at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Millet at Wikimedia Commons- Alternative Field Crops Manual: Millets