Purdah: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:261482 113105552113758 100002429423008 136150 6871109 n.jpg|thumb|261482 113105552113758 100002429423008 136150 6871109 n]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | “‘Purdah”’ or “‘pardah”’ (from [[Persian language | Persian ]] : پرده, meaning "curtain") is a religious and social institution of female seclusion in [[Muslim world | Muslim-majority countries]] and South Asian countries. The [[Arabic]] equivalent is [[hijab]]. The term purdah is predominantly used in South Asia. |

||

| ⚫ | Purdah has “visual, spatial, and ethical dimensions”. <ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> It refers three main components: veiling of women, segregation of sexes, and a set of norms and attitudes that sets boundaries for Muslim women’s moral conduct . <ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Purdah is primarily practiced in majority-Muslim countries and [[Hindu]] communities in [[South Asia]] ( [[India]], [[Pakistan]], [[Bangladesh]] ) . <ref>“Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah </ref> It varies broadly according to religions, region, nationality, cultures, and socioeconomic classes . <ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> . <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Purdah has “visual, spatial, and ethical dimensions”.<ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> It refers three main components: veiling of women, segregation of sexes, and a set of norms and attitudes that sets boundaries for Muslim women’s moral conduct.<ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Purdah is primarily practiced in majority-Muslim countries and [[Hindu]] communities in [[South Asia]] ([[India]], [[Pakistan]], [[Bangladesh]]).<ref>“Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah</ref> It varies broadly according to religions, region, nationality, cultures, and socioeconomic classes.<ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref><ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> |

||

==Origins== |

==Origins== |

||

===Pre-Islamic Roots=== |

===Pre-Islamic Roots=== |

||

Although purdah is commonly associated with Islam, many scholars argue that veiling and secluding women pre-dates Islam; these practices were commonly found among various groups in the Middle East such as [[Druze]], [[Christian]], and [[Jewish]] communities .<ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> For instance, the [[burqa]] existed in Arabia before Islam, and the mobility of upper-class women were restricted in Babylonia, Persian, and Byzantine Empire before the advent of Islam .<ref>Ahmed, Leila. ‘Women and the Advent of Islam.’ Women Living under Muslim Laws June 1989 - Mar. 1990, 7/8 : 5-15</ref> Historians believe purdah was acquired by the Muslims during the expansion of the Arab Empire into modern-day Iraq in the 7th century C.E. .<ref>“Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah</ref> Historians argue that Islam merely added religious significance to already existing local practices of the times. |

Although purdah is commonly associated with Islam, many scholars argue that veiling and secluding women pre-dates Islam; these practices were commonly found among various groups in the Middle East such as [[Druze]], [[Christian]], and [[ Jewish]] communities . <ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> For instance, the [[burqa]] existed in Arabia before Islam, and the mobility of upper-class women were restricted in Babylonia, Persian, and Byzantine Empire before the advent of Islam . <ref> Ahmed, Leila. ‘Women and the Advent of Islam.’ Women Living under Muslim Laws June 1989 - Mar. 1990, 7/8 : 5-15 </ref> Historians believe purdah was acquired by the Muslims during the expansion of the Arab Empire into modern-day Iraq in the 7th century C.E. . <ref>“Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah </ref> Historians argue that Islam merely added religious significance to already existing local practices of the times. |

||

=== From the Quran=== |

=== From the Quran=== |

||

Purdah was given religious significance under the [[Quran]], the Islamic holy book, and by the [[Hadith]].<ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> Rules about the purdah were listed in Verse 53 of Surah 33, where the Prophet Muhammed put his wives behind the curtain during the wedding feast of his newest wife Zeinab.<ref>Engineer, Asghar Ali. (1980) The Origin and Development of Islam, Orient Longman, Bombay</ref> |

Purdah was given religious significance under the [[Quran]], the Islamic holy book, and by the [[Hadith]] . <ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> Rules about the purdah were listed in Verse 53 of Surah 33, where the Prophet Muhammed put his wives behind the curtain during the wedding feast of his newest wife Zeinab. <ref> Engineer, Asghar Ali. (1980) The Origin and Development of Islam, Orient Longman, Bombay </ref> |

||

The verse reads: |

The verse reads: |

||

{{Quote| O ye who believe! Enter not the Prophet’s houses until leave is given you for a meal [...]. And when ye have taken your meal, disperse, without seeking familiar talk, such (behaviour) annoys the Prophet [...]. And when ye ask (his ladies) for anything you want, ask them from before a screen: that makes for greater purity for your hearts and for theirs.” ({{cite quran|53|33}})}} |

{{Quote| O ye who believe! Enter not the Prophet’s houses until leave is given you for a meal [...]. And when ye have taken your meal, disperse, without seeking familiar talk, such (behaviour) annoys the Prophet [...]. And when ye ask (his ladies) for anything you want, ask them from before a screen: that makes for greater purity for your hearts and for theirs.” ({{cite quran|53|33}})}} |

||

The Quranic verses stipulate modesty for both men and women, but lists many more restrictions for women’s movement.<ref>Engineer, Asghar Ali. (1980) The Origin and Development of Islam, Orient Longman, Bombay</ref> The most explicit passage in the Quran that regulates purdah and female modesty is Verse 31 of Surah 24, which specifies the men whom women may interact freely.<ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> |

The Quranic verses stipulate modesty for both men and women, but lists many more restrictions for women’s movement. <ref> Engineer, Asghar Ali. (1980) The Origin and Development of Islam, Orient Longman, Bombay </ref> The most explicit passage in the Quran that regulates purdah and female modesty is Verse 31 of Surah 24, which specifies the men whom women may interact freely. <ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> |

||

{{Quote| Say to the believing men that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty: that will make for greater purity for them [...]. And say to the believing women that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty; that they should not display their beauty and ornaments except what (ordinarily) appear thereof; that they should draw their veils over their bosoms and not display their beauty except to their husbands, their fathers, their husbands’ fathers, their sons, their husbands’ sons, their brothers or their brothers’ sons, or their sisters’ sons, or their women, or the slaves whom their right hands possess, or male attendants free of sexual desires. Or small children who have no carnal knowledge of women; And that they should not strike their feet in order to draw attention to their hidden ornaments. ({{cite quran|24|31}})}} |

{{Quote| Say to the believing men that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty: that will make for greater purity for them [...]. And say to the believing women that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty; that they should not display their beauty and ornaments except what (ordinarily) appear thereof; that they should draw their veils over their bosoms and not display their beauty except to their husbands, their fathers, their husbands’ fathers, their sons, their husbands’ sons, their brothers or their brothers’ sons, or their sisters’ sons, or their women, or the slaves whom their right hands possess, or male attendants free of sexual desires. Or small children who have no carnal knowledge of women; And that they should not strike their feet in order to draw attention to their hidden ornaments. ({{cite quran|24|31}})}} |

||

Lastly, Verse 59 of Surah 33 reveals a historical context of the |

Lastly, Verse 59 of Surah 33 reveals a historical context of the purdah-- it explains the necessity of a covering for women when they go outside as a way to signify their status so they would not be harassed by the [[Munafiq | hypocrites]] who habitually harassed female slave women. <ref> Mernissi, Fatima. (1993) Women and Islam, 1987 Trans. Mary Jo Lakeland, 1991, Kali for Women, New Delhi </ref> |

||

{{Quote| O Prophet! Tell thy wives and daughters and the believing women that they should cast their outer garments (jilbab) over their persons (when out of doors): That is most convenient that they should be known (as such) and not molested. ({{cite quran|59|33}})}} |

{{Quote| O Prophet! Tell thy wives and daughters and the believing women that they should cast their outer garments (jilbab) over their persons (when out of doors): That is most convenient that they should be known (as such) and not molested. ({{cite quran|59|33}})}} |

||

Notably, during the Prophet Muhammad’s life, the purdah was restricted to only women of his family and tribe.<ref>Ahmed, Leila. ‘Women and the Advent of Islam.’ Women Living under Muslim Laws June 1989 - Mar. 1990, 7/8 : 5-15</ref> |

Notably, during the Prophet Muhammad’s life, the purdah was restricted to only women of his family and tribe. <ref> Ahmed, Leila. ‘Women and the Advent of Islam.’ Women Living under Muslim Laws June 1989 - Mar. 1990, 7/8 : 5-15 </ref> |

||

=== Adoption and Spreading=== |

=== Adoption and Spreading=== |

||

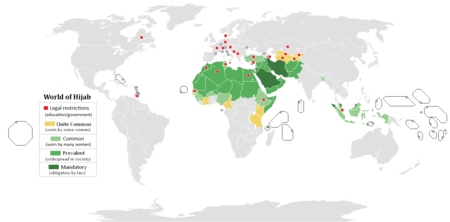

[[File:Hijab world2.png|450px|thumb|A map showing the prevalence of the Hijab{{Citation needed|date=September 2011}}]] |

[[File:Hijab world2.png|450px|thumb|A map showing the prevalence of the Hijab{{Citation needed|date=September 2011}}]] |

||

Historians believe purdah was originally a [[Persian]] practice that the Muslims adopted during the Arab conquest of modern-day [[Iraq]] in the 7th century C.E. .<ref>“Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah</ref> Later, Muslim rule of northern India during the [[Mughal Empire]] influenced the practice of Hinduism, and purdah spread to the Hindu upper classes of northern India.<ref>“Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah</ref> During the British colonialism period in India, purdah observance was widespread and strictly-adhered to among the Muslim minority.<ref>“Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah</ref> In modern times, the practice of veiling and secluding women is still present in mainly Islamic countries and South Asian countries.<ref>“Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah</ref> However, the practice is not monolithic. Purdah takes on different forms and significance depending on the region, time, socioeconomic status, and local culture.<ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> |

Historians believe purdah was originally a [[Persian]] practice that the Muslims adopted during the Arab conquest of modern-day [[Iraq]] in the 7th century C.E. . <ref>“Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah </ref> Later, Muslim rule of northern India during the [[Mughal Empire]] influenced the practice of Hinduism, and purdah spread to the Hindu upper classes of northern India. <ref>“Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah </ref> During the British colonialism period in India, purdah observance was widespread and strictly-adhered to among the Muslim minority. <ref>“Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah </ref> In modern times, the practice of veiling and secluding women is still present in mainly Islamic countries and South Asian countries. <ref>“Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah </ref> However, the practice is not monolithic. Purdah takes on different forms and significance depending on the region, time, socioeconomic status, and local culture. <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> |

||

==Rationale== |

==Rationale== |

||

===Protection and Patriarchy=== |

===Protection and Patriarchy=== |

||

Some scholars argue that purdah was initially designed to protect women from being harassed, but later these practices became a way to justify efforts to subjugate women and limit their mobility and freedom .<ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> However, others argue that these practices were always in place as local custom, but were later adopted by religious rhetoric to control female behavior .<ref>Shaheed, F. “The Cultural Articulation of Patriarchy: Legal Systems, Islam and Women.” South Asia Bulletin 6, no. 1 (1986): 38–44.</ref> |

Some scholars argue that purdah was initially designed to protect women from being harassed, but later these practices became a way to justify efforts to subjugate women and limit their mobility and freedom . <ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> However, others argue that these practices were always in place as local custom, but were later adopted by religious rhetoric to control female behavior . <ref>Shaheed, F. “The Cultural Articulation of Patriarchy: Legal Systems, Islam and Women.” South Asia Bulletin 6, no. 1 (1986): 38–44. </ref> |

||

===Respect=== |

===Respect=== |

||

Some view purdah as a symbol of honor, respect, and dignity. It is seen as a practice that allows women to be judged by their inner beauty rather than physical beauty .<ref>Arnett, Susan. King's College History Department, "Purdah." Last modified 2001. Accessed March 18, 2013. http://departments.kings.edu/womens_history/purdah.html.</ref> |

Some view purdah as a symbol of honor, respect, and dignity. It is seen as a practice that allows women to be judged by their inner beauty rather than physical beauty . <ref> Arnett, Susan. King's College History Department, "Purdah." Last modified 2001. Accessed March 18, 2013. http://departments.kings.edu/womens_history/purdah.html. </ref> |

||

===Economic === |

===Economic === |

||

In many societies, the seclusion of women to the domestic sphere is a demonstration of higher socioeconomic status and prestige because women are not needed for manual labor outside the home .<ref> |

In many societies, the seclusion of women to the domestic sphere is a demonstration of higher socioeconomic status and prestige because women are not needed for manual labor outside the home . <ref> Veiling and the Seclusion of Women. US Library of Congress [http://countrystudies.us/india/84.htm] </ref> |

||

===Individual motivations=== |

===Individual motivations=== |

||

Rationale for individual women keeping purdah are complex and can be a combination of motivations: religious, cultural (desire for authentic cultural dress), political (Islamization of the society), economic (status symbol, protection from the public gaze), psychological (detachment from public sphere to gain respect), fashion and decorative purposes, and empowerment (donning veils to move in public space) .<ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> |

Rationale for individual women keeping purdah are complex and can be a combination of motivations: religious, cultural (desire for authentic cultural dress), political (Islamization of the society), economic (status symbol, protection from the public gaze), psychological (detachment from public sphere to gain respect), fashion and decorative purposes, and empowerment (donning veils to move in public space) . <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> |

||

==Dress== |

==Dress== |

||

See [[Hijab by country]] |

See [[Hijab by country]] |

||

| Line 54: | Line 63: | ||

*[[Chador]] : a full-body-length semicircle of fabric open down the front, that covers the female’s head, most commonly found on Iranian women in public spaces |

*[[Chador]] : a full-body-length semicircle of fabric open down the front, that covers the female’s head, most commonly found on Iranian women in public spaces |

||

* [[Burqa]] : a head-to-toe garment women wear when moving through public space, mainly found in Afghanistan, India, Pakistan, Israel, and Syria. |

* [[Burqa]] : a head-to-toe garment women wear when moving through public space, mainly found in Afghanistan, India, Pakistan, Israel, and Syria. |

||

* [[Ghoongat]] : a veil to cover the face of married Hindu women in India |

* [[Ghoongat]] : a veil to cover the face of married Hindu women in India |

||

==Conduct and Seclusion== |

==Conduct and Seclusion== |

||

Another important aspect of purdah is modesty for women, which includes minimizing the movement of women in public spaces and interactions of women with other males. The specific form varies widely based on religion, region, class, and culture. For instance, for some purdah might mean never leaving the home unless accompanied by a male relative, or limiting interactions to only other women and male relatives (for some Muslims) or avoiding all males outside of the immediate family (for some Hindus ) .<ref>Papanek, Hanna. “Purdah: Separate Worlds and Symbolic Shelter.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 15, no. 03 (1973): 289–325. doi:10.1017/S001041750000712X.</ref> For Muslims, seclusion begins at puberty while for Hindus, seclusion begins after marriage .<ref>Papanek, Hanna. “Purdah: Separate Worlds and Symbolic Shelter.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 15, no. 03 (1973): 289–325. doi:10.1017/S001041750000712X.</ref> |

Another important aspect of purdah is modesty for women, which includes minimizing the movement of women in public spaces and interactions of women with other males. The specific form varies widely based on religion, region, class, and culture. For instance, for some purdah might mean never leaving the home unless accompanied by a male relative, or limiting interactions to only other women and male relatives (for some Muslims) or avoiding all males outside of the immediate family (for some Hindus ) . <ref> Papanek, Hanna. “Purdah: Separate Worlds and Symbolic Shelter.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 15, no. 03 (1973): 289–325. doi:10.1017/S001041750000712X. </ref> For Muslims, seclusion begins at puberty while for Hindus, seclusion begins after marriage . <ref> Papanek, Hanna. “Purdah: Separate Worlds and Symbolic Shelter.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 15, no. 03 (1973): 289–325. doi:10.1017/S001041750000712X. </ref> |

||

==Effects of Purdah== |

==Effects of Purdah== |

||

===Psychology and Health=== |

===Psychology and Health=== |

||

By restricting women’s mobility, purdah results in the social and physical isolation of women .<ref>Michael A. Koenig, Saifuddin Ahmed, Mian Bazle Hossain, and A. B. M. Khorshed Alam Mozumder. “Women’s Status and Domestic Violence in Rural Bangladesh: Individual- and Community-level Effects.” Demography 40, no. 2 (May 1, 2003): 269–288. doi:10.1353/dem.2003.0014.</ref> Lack of a strong social network places women in a position of vulnerability with her husband and her husband’s family. Studies have shown that in conservative rural Bangladeshi communities, adherence to purdah is positively correlated with risk for domestic violence .<ref>Michael A. Koenig, Saifuddin Ahmed, Mian Bazle Hossain, and A. B. M. Khorshed Alam Mozumder. “Women’s Status and Domestic Violence in Rural Bangladesh: Individual- and Community-level Effects.” Demography 40, no. 2 (May 1, 2003): 269–288. doi:10.1353/dem.2003.0014.</ref> |

By restricting women’s mobility, purdah results in the social and physical isolation of women . <ref> Michael A. Koenig, Saifuddin Ahmed, Mian Bazle Hossain, and A. B. M. Khorshed Alam Mozumder. “Women’s Status and Domestic Violence in Rural Bangladesh: Individual- and Community-level Effects.” Demography 40, no. 2 (May 1, 2003): 269–288. doi:10.1353/dem.2003.0014. </ref> Lack of a strong social network places women in a position of vulnerability with her husband and her husband’s family. Studies have shown that in conservative rural Bangladeshi communities, adherence to purdah is positively correlated with risk for domestic violence . <ref> Michael A. Koenig, Saifuddin Ahmed, Mian Bazle Hossain, and A. B. M. Khorshed Alam Mozumder. “Women’s Status and Domestic Violence in Rural Bangladesh: Individual- and Community-level Effects.” Demography 40, no. 2 (May 1, 2003): 269–288. doi:10.1353/dem.2003.0014. </ref> |

||

===Economic participation=== |

===Economic participation=== |

||

By restricting women’s mobility, purdah places severe limits on women’s ability to participate in gainful employment. The ideology of purdah constricts women in the domestic sphere for reproductive role and places men in productive role as breadwinners who move through public space .<ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> However, due to economic needs and shifts in gender relations, some women are compelled to break purdah to gain income .<ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> Across countries, women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds tend to observe purdah less because they face greater financial pressures to work and gain income .<ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> For instance, rural women in Bangladesh have been found to be less concerned with propriety and purdah, and take up work where available, migrating if they need to. .<ref>Kabeer, N. “Poverty, purdah and women’s survival strategies in rural Bangladesh.” (1990): 134–148.</ref> They take up work in a variety of sectors from agriculture to manufacturing to the sex trade .<ref>Kabeer, N. “Poverty, purdah and women’s survival strategies in rural Bangladesh.” (1990): 134–148.</ref> However, other studies found that purdah still plays a significant role in women’s decisions to participate in the workforce, often prohibiting them from taking opportunities they would otherwise.<ref>Amin, Sajeda. “The Poverty–Purdah Trap in Rural Bangladesh: Implications for Women’s Roles in the Family.” Development and Change 28, no. 2 (1997): 213–233. doi 10.1111/1467-7660.00041.</ref> The degree to which women observe purdah and the pressures they face to conform or to earn income vary with their socioeconomic class. |

By restricting women’s mobility, purdah places severe limits on women’s ability to participate in gainful employment. The ideology of purdah constricts women in the domestic sphere for reproductive role and places men in productive role as breadwinners who move through public space . <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> However, due to economic needs and shifts in gender relations, some women are compelled to break purdah to gain income . <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> Across countries, women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds tend to observe purdah less because they face greater financial pressures to work and gain income . <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> For instance, rural women in Bangladesh have been found to be less concerned with propriety and purdah, and take up work where available, migrating if they need to. . <ref>Kabeer, N. “Poverty, purdah and women’s survival strategies in rural Bangladesh.” (1990): 134–148. </ref> They take up work in a variety of sectors from agriculture to manufacturing to the sex trade . <ref>Kabeer, N. “Poverty, purdah and women’s survival strategies in rural Bangladesh.” (1990): 134–148. </ref> However, other studies found that purdah still plays a significant role in women’s decisions to participate in the workforce, often prohibiting them from taking opportunities they would otherwise. <ref> Amin, Sajeda. “The Poverty–Purdah Trap in Rural Bangladesh: Implications for Women’s Roles in the Family.” Development and Change 28, no. 2 (1997): 213–233. doi 10.1111/1467-7660.00041. </ref> The degree to which women observe purdah and the pressures they face to conform or to earn income vary with their socioeconomic class. |

||

===Political participation=== |

===Political participation=== |

||

| ⚫ | Social and mobility restrictions under purdah severely limit women's involvement in political decision making in government institutions and in the judiciary .<ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> Lack of mobility and discouragement from participating in political life means women cannot easily exercise their right to vote, run for political office, participate in trade unions, or participate in community level decision-making .<ref>Shaheed, F. “The Cultural Articulation of Patriarchy: Legal Systems, Islam and Women.” South Asia Bulletin 6, no. 1 (1986): 38–44.</ref> Women’s limited participation in political decision-making therefore results in policies that do not sufficiently address needs and rights of women in areas such as access to healthcare, education and employment opportunities, property ownership, justice, and others .<ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> Gender imbalance in policy-making also reinforces institutionalization of gender disparities .<ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | In [[Tunisia]] and [[Turkey]], religious veiling is banned in public schools, universities, and government buildings as a measure to discourage displays of political Islam or fundamentalism .<ref>Turkey headscarf ruling condemned Al Jazeera English (07 June 2008). Retrieved on February 2013.</ref><ref>Abdelhadi, Magdi Tunisia attacked over headscarves, BBC News, September 26, 2006. Accessed February 2013.</ref> In western Europe, veiling is seen as symbol of Islamic presence, and movements to ban veils have stirred great controversy. For instance, since 2004 France has banned all overt religious symbols including the Muslim headscarf .<ref>French MPs back headscarf ban BBC News (BBC). Retrieved on 13 February 2009.</ref> In Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh where the word purdah is primarily used, the government has no policies either for or against veiling. |

||

| ⚫ | Social and mobility restrictions under purdah severely limit women's involvement in political decision making in government institutions and in the judiciary . <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> Lack of mobility and discouragement from participating in political life means women cannot easily exercise their right to vote, run for political office, participate in trade unions, or participate in community level decision-making . <ref>Shaheed, F. “The Cultural Articulation of Patriarchy: Legal Systems, Islam and Women.” South Asia Bulletin 6, no. 1 (1986): 38–44. </ref>. Women’s limited participation in political decision-making therefore results in policies that do not sufficiently address needs and rights of women in areas such as access to healthcare, education and employment opportunities, property ownership, justice, and others . <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> Gender imbalance in policy-making also reinforces institutionalization of gender disparities . <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> |

||

==Influences on Purdah== |

==Influences on Purdah== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | In [[Tunisia]] and [[Turkey]], religious veiling is banned in public schools, universities, and government buildings as a measure to discourage displays of political Islam or fundamentalism . <ref> Turkey headscarf ruling condemned Al Jazeera English (07 June 2008). Retrieved on February 2013. </ref> . <ref> Abdelhadi, Magdi Tunisia attacked over headscarves, BBC News, September 26, 2006. Accessed February 2013. </ref> In western Europe, veiling is seen as symbol of Islamic presence, and movements to ban veils have stirred great controversy. For instance, since 2004 France has banned all overt religious symbols including the Muslim headscarf . <ref> French MPs back headscarf ban BBC News (BBC). Retrieved on 13 February 2009.</ref >. In Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh where the word purdah is primarily used, the government has no policies either for or against veiling. |

||

===Women’s Movements=== |

===Women’s Movements=== |

||

[[File:Protest against Non-representation of Women.jpg|thumb|Protest against Non-representation of Women]] |

[[File:Protest against Non-representation of Women.jpg|thumb|Protest against Non-representation of Women]] |

||

Women have been engaging in efforts to challenge the gender inequality resulting from purdah. For instance, women in Pakistan (mainly from the middle and upper-classes) organized trade unions and exercise their right to vote and influence decision making .<ref>Shaheed, F. “The Cultural Articulation of Patriarchy: Legal Systems, Islam and Women.” South Asia Bulletin 6, no. 1 (1986): 38–44.</ref> However, their opponents accuse these women of falling for the pernicious influence of Westernization and turning their backs on tradition. .<ref>Shaheed, F. “The Cultural Articulation of Patriarchy: Legal Systems, Islam and Women.” South Asia Bulletin 6, no. 1 (1986): 38–44.</ref> |

Women have been engaging in efforts to challenge the gender inequality resulting from purdah. For instance, women in Pakistan (mainly from the middle and upper-classes) organized trade unions and exercise their right to vote and influence decision making . <ref>Shaheed, F. “The Cultural Articulation of Patriarchy: Legal Systems, Islam and Women.” South Asia Bulletin 6, no. 1 (1986): 38–44. </ref> However, their opponents accuse these women of falling for the pernicious influence of Westernization and turning their backs on tradition. . <ref>Shaheed, F. “The Cultural Articulation of Patriarchy: Legal Systems, Islam and Women.” South Asia Bulletin 6, no. 1 (1986): 38–44. </ref> |

||

===Globalization and migration=== |

===Globalization and migration=== |

||

| ⚫ | Globalization and Muslim women returning from diasporas has influenced Pakistani women’s purdah practice in areas outside of religious significance. .<ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> One major influence is the desire to be modern and keep up with latest fashion or refusal to do so as a source of autonomy and power .<ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> Simultaneously, due to modernization in many urban areas, purdah and face-veiling are seen as unsophisticated and backwards, creating a trend in less strict observance of purdah .<ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Globalization and Muslim women returning from diasporas has influenced Pakistani women’s purdah practice in areas outside of religious significance. . <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> One major influence is the desire to be modern and keep up with latest fashion or refusal to do so as a source of autonomy and power . <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> Simultaneously, due to modernization in many urban areas, purdah and face-veiling are seen as unsophisticated and backwards, creating a trend in less strict observance of purdah . <ref> Veiling and the Seclusion of Women. US Library of Congress [http://countrystudies.us/india/84.htm] </ref> |

||

| ⚫ | For Muslim South Asian diaspora living in secular non-Muslim communities such as Pakistani-Americans, attitudes about purdah have changed to be less strict. .<ref>Bokhari, Syeda Saba. “Attitudes of Migrant Pakistani-muslim Families Towards Purdah and the Education of Women in a Secular Environment.” Dissertation Abstracts International. Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 58, no. 01 (July 1997): 193–193.</ref> As it pertains to education and economic opportunities, these immigrant families hold less conservative views about purdah after moving to America; for the daughters who do choose to wear the veil, they usually do so out of their own volition as a connection to their Islamic roots and culture .<ref>Bokhari, Syeda Saba. “Attitudes of Migrant Pakistani-muslim Families Towards Purdah and the Education of Women in a Secular Environment.” Dissertation Abstracts International. Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 58, no. 01 (July 1997): 193–193.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | For Muslim South Asian diaspora living in secular non-Muslim communities such as Pakistani-Americans, attitudes about purdah have changed to be less strict. . <ref> Bokhari, Syeda Saba. “Attitudes of Migrant Pakistani-muslim Families Towards Purdah and the Education of Women in a Secular Environment.” Dissertation Abstracts International. Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 58, no. 01 (July 1997): 193–193. </ref> As it pertains to education and economic opportunities, these immigrant families hold less conservative views about purdah after moving to America; for the daughters who do choose to wear the veil, they usually do so out of their own volition as a connection to their Islamic roots and culture . <ref> Bokhari, Syeda Saba. “Attitudes of Migrant Pakistani-muslim Families Towards Purdah and the Education of Women in a Secular Environment.” Dissertation Abstracts International. Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 58, no. 01 (July 1997): 193–193. </ref> |

||

===Islamization=== |

===Islamization=== |

||

Nations such as Pakistan have been swinging to more conservative laws and policies that use rhetoric of following Islamic law, sometimes termed [[Islamization]].<ref>Shahab, Rafi Ullah. (1993). Muslim Women in Political Power. Lahore: Maqbool Academy</ref> The ideology is reinforcing traditional culture, traditional women’s roles in the domestic sphere, and the need to protect women’s honor. The result is policies that reinforce cultural norms that limit female mobility in the public sphere, promotion of gender segregation, and institutionalization of gender disparities.<ref>Jalal, Ayesha (1991). The Convenience of Subservience: Women in the State of Pakistan. Kandiyoti, Deniz., Women, Islam and the State. Philadelphia: Temple University Press</ref> |

Nations such as Pakistan have been swinging to more conservative laws and policies that use rhetoric of following Islamic law, sometimes termed [[Islamization]]. <ref> Shahab, Rafi Ullah. (1993). Muslim Women in Political Power. Lahore: Maqbool Academy </ref> The ideology is reinforcing traditional culture, traditional women’s roles in the domestic sphere, and the need to protect women’s honor. The result is policies that reinforce cultural norms that limit female mobility in the public sphere, promotion of gender segregation, and institutionalization of gender disparities. <ref>Jalal, Ayesha (1991). The Convenience of Subservience: Women in the State of Pakistan. Kandiyoti, Deniz., Women, Islam and the State. Philadelphia: Temple University Press</ref> |

||

==Controversy around women’s agency== |

==Controversy around women’s agency== |

||

===Purdah as protection=== |

===Purdah as protection=== |

||

Some scholars argue that purdah was originally designed to protect women from being harassed and seen as sexual objects .<ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> In contemporary times, some men and women still interpret the purdah as a way to protect women’s safety while moving in public sphere .<ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> Observing purdah is also seen as a way to uphold women’s honor and virtuous conduct .<ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> However, critics point out that this view engages victim-blaming and places the onus of preventing sexual assault on women rather than the perpetrators themselves. |

Some scholars argue that purdah was originally designed to protect women from being harassed and seen as sexual objects . <ref>Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51</ref> In contemporary times, some men and women still interpret the purdah as a way to protect women’s safety while moving in public sphere . <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> Observing purdah is also seen as a way to uphold women’s honor and virtuous conduct . <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> However, critics point out that this view engages victim-blaming and places the onus of preventing sexual assault on women rather than the perpetrators themselves. |

||

===Purdah as oppression=== |

===Purdah as oppression=== |

||

| ⚫ | Purdah is often criticized as oppression of women by limiting female autonomy, freedom of movement, and access to resources such as education, employment, and political participation.<ref>Engineer, Asghar Ali. (1980) The Origin and Development of Islam, Orient Longman, Bombay</ref> Some scholars such as P. Singh and Roy interpret purdah as a form of male domination in the public sphere, and an “eclipse of Muslim woman’s identity and individuality” .<ref>Singh, Prahlad (2004). “Purdah: the seclusion of body and mind”. Abstracts of Sikh Studies, Vol 5, issue 1</ref> According to scholars such as Elizabeth White, “purdah is an accommodation to and a means of perpetuating the perceived differences between the sexes: the male being self-reliant and aggressive, the female weak, irresponsible, and in need of protection” .<ref>White, Elizabeth H. “Purdah.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 2, no. 1 (April 1, 1977): 31–42. doi:10.2307/3346105</ref> Geraldine Books writes “in both cases [of spatial separation and veiling], women are expected to sacrifice their comfort and freedom to service the requirements of male sexuality: either to repress or to stimulate the male sex urge”.<ref>Brooks, Geraldine. Nine Parts of Desire: The Hidden World of Islamic Women. New York: Doubleday, 1995. </ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Purdah is often criticized as oppression of women by limiting female autonomy, freedom of movement, and access to resources such as education, employment, and political participation. <ref> Engineer, Asghar Ali. (1980) The Origin and Development of Islam, Orient Longman, Bombay </ref> Some scholars such as P. Singh and Roy interpret purdah as a form of male domination in the public sphere, and an “eclipse of Muslim woman’s identity and individuality” . <ref> Singh, Prahlad (2004). “Purdah: the seclusion of body and mind”. Abstracts of Sikh Studies, Vol 5, issue 1</ref> According to scholars such as Elizabeth White, “purdah is an accommodation to and a means of perpetuating the perceived differences between the sexes: the male being self-reliant and aggressive, the female weak, irresponsible, and in need of protection” . <ref> White, Elizabeth H. “Purdah.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 2, no. 1 (April 1, 1977): 31–42. doi:10.2307/3346105</ref> Geraldine Books writes “in both cases [of spatial separation and veiling], women are expected to sacrifice their comfort and freedom to service the requirements of male sexuality: either to repress or to stimulate the male sex urge”. <ref> Brooks, Geraldine. Nine Parts of Desire: The Hidden World of Islamic Women. New York: Doubleday, 1995. </ref> |

||

| ⚫ | When purdah is institutionalized into laws, it limits opportunity, autonomy, and [[agency]] in both private and public life .<ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> The result is policies that reinforce cultural norms that limit female mobility in the public sphere, promotion of gender segregation, and institutionalization of gender disparities .<ref>Jalal, Ayesha (1991). The Convenience of Subservience: Women in the State of Pakistan. Kandiyoti, Deniz., Women, Islam and the State. Philadelphia: Temple University Press</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | When purdah is institutionalized into laws, it limits opportunity, autonomy, and [[agency]] in both private and public life . <ref>Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310</ref> The result is policies that reinforce cultural norms that limit female mobility in the public sphere, promotion of gender segregation, and institutionalization of gender disparities . <ref> Jalal, Ayesha (1991). The Convenience of Subservience: Women in the State of Pakistan. Kandiyoti, Deniz., Women, Islam and the State. Philadelphia: Temple University Press</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Sometimes reactions to purdah adherence can become violent. For instance in 2001 in Srinagar, India, four young Muslim women were victimized by acid attacks for not veiling themselves in public; similar threats and attacks have occurred in Pakistan and Kashmir .<ref>Nelson, Dean. "Kashmir women ordered to cover up or risk acid attack." The Telegraph, , sec. World, August 13, 2012. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/india/9472909/Kashmir-women-ordered-to-cover-up-or-risk-acid-attack.html (accessed March 18, 2013).</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Sometimes reactions to purdah adherence can become violent. For instance in 2001 in Srinagar, India, four young Muslim women were victimized by acid attacks for not veiling themselves in public; similar threats and attacks have occurred in Pakistan and Kashmir . <ref> Nelson, Dean. "Kashmir women ordered to cover up or risk acid attack." The Telegraph, , sec. World, August 13, 2012. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/india/9472909/Kashmir-women-ordered-to-cover-up-or-risk-acid-attack.html (accessed March 18, 2013). </ref> |

||

===Purdah as empowerment=== |

===Purdah as empowerment=== |

||

The revival of purdah in modern times is sometimes perceived as a statement for progressive gender relations. Some women wear veils and head coverings as a symbol for protection and freedom of mobility. They perceive purdah as an empowerment tool, to exercise their rights to access public space for education and economic independence. For instance, in rural Bangladeshi villages, women who wear the burkha were found to have higher social participation, visibility, which overall contributes to an increase in women’s status .<ref>Feldman, Shelley, and Florence McCarthy. "Purdah and Changing Patterns of Social Control among Rural Women in Bangladesh." Journal of Marriage and Family. 45. no. 4 (1983): 949-959. http://www.jstor.org/stable/351808 . (accessed February 17, 2013).</ref> |

The revival of purdah in modern times is sometimes perceived as a statement for progressive gender relations. Some women wear veils and head coverings as a symbol for protection and freedom of mobility. They perceive purdah as an empowerment tool, to exercise their rights to access public space for education and economic independence. For instance, in rural Bangladeshi villages, women who wear the burkha were found to have higher social participation, visibility, which overall contributes to an increase in women’s status . <ref> Feldman, Shelley, and Florence McCarthy. "Purdah and Changing Patterns of Social Control among Rural Women in Bangladesh." Journal of Marriage and Family. 45. no. 4 (1983): 949-959. http://www.jstor.org/stable/351808 . (accessed February 17, 2013). </ref> |

||

==See |

==See Also == |

||

*[[Awrah]] |

*[[Awrah]] |

||

*[[Burqa]] |

*[[Burqa]] |

||

| Line 117: | Line 132: | ||

*[[Women in Pakistan]] |

*[[Women in Pakistan]] |

||

*[[Zenana]] |

*[[Zenana]] |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

{{Islamic female dress}} |

|||

[[Category:Islamic dress (female)]] |

|||

[[Category:Afghan clothing]] |

|||

[[Category:Indian clothing]] |

|||

[[Category:Pakistani clothing]] |

|||

[[Category:Purdah| ]] |

|||

Revision as of 18:41, 10 April 2013

“‘Purdah”’ or “‘pardah”’ (from Persian : پرده, meaning "curtain") is a religious and social institution of female seclusion in Muslim-majority countries and South Asian countries. The Arabic equivalent is hijab. The term purdah is predominantly used in South Asia.

Purdah has “visual, spatial, and ethical dimensions”. [1] It refers three main components: veiling of women, segregation of sexes, and a set of norms and attitudes that sets boundaries for Muslim women’s moral conduct . [2]

Purdah is primarily practiced in majority-Muslim countries and Hindu communities in South Asia ( India, Pakistan, Bangladesh ) . [3] It varies broadly according to religions, region, nationality, cultures, and socioeconomic classes . [4] . [5]

Origins

Pre-Islamic Roots

Although purdah is commonly associated with Islam, many scholars argue that veiling and secluding women pre-dates Islam; these practices were commonly found among various groups in the Middle East such as Druze, Christian, and Jewish communities . [6] For instance, the burqa existed in Arabia before Islam, and the mobility of upper-class women were restricted in Babylonia, Persian, and Byzantine Empire before the advent of Islam . [7] Historians believe purdah was acquired by the Muslims during the expansion of the Arab Empire into modern-day Iraq in the 7th century C.E. . [8] Historians argue that Islam merely added religious significance to already existing local practices of the times.

From the Quran

Purdah was given religious significance under the Quran, the Islamic holy book, and by the Hadith . [9] Rules about the purdah were listed in Verse 53 of Surah 33, where the Prophet Muhammed put his wives behind the curtain during the wedding feast of his newest wife Zeinab. [10]

The verse reads:

O ye who believe! Enter not the Prophet’s houses until leave is given you for a meal [...]. And when ye have taken your meal, disperse, without seeking familiar talk, such (behaviour) annoys the Prophet [...]. And when ye ask (his ladies) for anything you want, ask them from before a screen: that makes for greater purity for your hearts and for theirs.” ([Quran 53:33])

The Quranic verses stipulate modesty for both men and women, but lists many more restrictions for women’s movement. [11] The most explicit passage in the Quran that regulates purdah and female modesty is Verse 31 of Surah 24, which specifies the men whom women may interact freely. [12]

Say to the believing men that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty: that will make for greater purity for them [...]. And say to the believing women that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty; that they should not display their beauty and ornaments except what (ordinarily) appear thereof; that they should draw their veils over their bosoms and not display their beauty except to their husbands, their fathers, their husbands’ fathers, their sons, their husbands’ sons, their brothers or their brothers’ sons, or their sisters’ sons, or their women, or the slaves whom their right hands possess, or male attendants free of sexual desires. Or small children who have no carnal knowledge of women; And that they should not strike their feet in order to draw attention to their hidden ornaments. ([Quran 24:31])

Lastly, Verse 59 of Surah 33 reveals a historical context of the purdah-- it explains the necessity of a covering for women when they go outside as a way to signify their status so they would not be harassed by the hypocrites who habitually harassed female slave women. [13]

O Prophet! Tell thy wives and daughters and the believing women that they should cast their outer garments (jilbab) over their persons (when out of doors): That is most convenient that they should be known (as such) and not molested. ([Quran 59:33])

Notably, during the Prophet Muhammad’s life, the purdah was restricted to only women of his family and tribe. [14]

Adoption and Spreading

Historians believe purdah was originally a Persian practice that the Muslims adopted during the Arab conquest of modern-day Iraq in the 7th century C.E. . [15] Later, Muslim rule of northern India during the Mughal Empire influenced the practice of Hinduism, and purdah spread to the Hindu upper classes of northern India. [16] During the British colonialism period in India, purdah observance was widespread and strictly-adhered to among the Muslim minority. [17] In modern times, the practice of veiling and secluding women is still present in mainly Islamic countries and South Asian countries. [18] However, the practice is not monolithic. Purdah takes on different forms and significance depending on the region, time, socioeconomic status, and local culture. [19]

Rationale

Protection and Patriarchy

Some scholars argue that purdah was initially designed to protect women from being harassed, but later these practices became a way to justify efforts to subjugate women and limit their mobility and freedom . [20] However, others argue that these practices were always in place as local custom, but were later adopted by religious rhetoric to control female behavior . [21]

Respect

Some view purdah as a symbol of honor, respect, and dignity. It is seen as a practice that allows women to be judged by their inner beauty rather than physical beauty . [22]

Economic

In many societies, the seclusion of women to the domestic sphere is a demonstration of higher socioeconomic status and prestige because women are not needed for manual labor outside the home . [23]

Individual motivations

Rationale for individual women keeping purdah are complex and can be a combination of motivations: religious, cultural (desire for authentic cultural dress), political (Islamization of the society), economic (status symbol, protection from the public gaze), psychological (detachment from public sphere to gain respect), fashion and decorative purposes, and empowerment (donning veils to move in public space) . [24]

Dress

See Hijab by country

One aspect of purdah is the physical veiling of women through coverings such as

- Dupatta : a scarf or end of the sari that cover the tops of their heads in northern Indian, traditionally dressed women wear

- Chador : a full-body-length semicircle of fabric open down the front, that covers the female’s head, most commonly found on Iranian women in public spaces

- Burqa : a head-to-toe garment women wear when moving through public space, mainly found in Afghanistan, India, Pakistan, Israel, and Syria.

- Ghoongat : a veil to cover the face of married Hindu women in India

Conduct and Seclusion

Another important aspect of purdah is modesty for women, which includes minimizing the movement of women in public spaces and interactions of women with other males. The specific form varies widely based on religion, region, class, and culture. For instance, for some purdah might mean never leaving the home unless accompanied by a male relative, or limiting interactions to only other women and male relatives (for some Muslims) or avoiding all males outside of the immediate family (for some Hindus ) . [25] For Muslims, seclusion begins at puberty while for Hindus, seclusion begins after marriage . [26]

Effects of Purdah

Psychology and Health

By restricting women’s mobility, purdah results in the social and physical isolation of women . [27] Lack of a strong social network places women in a position of vulnerability with her husband and her husband’s family. Studies have shown that in conservative rural Bangladeshi communities, adherence to purdah is positively correlated with risk for domestic violence . [28]

Economic participation

By restricting women’s mobility, purdah places severe limits on women’s ability to participate in gainful employment. The ideology of purdah constricts women in the domestic sphere for reproductive role and places men in productive role as breadwinners who move through public space . [29] However, due to economic needs and shifts in gender relations, some women are compelled to break purdah to gain income . [30] Across countries, women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds tend to observe purdah less because they face greater financial pressures to work and gain income . [31] For instance, rural women in Bangladesh have been found to be less concerned with propriety and purdah, and take up work where available, migrating if they need to. . [32] They take up work in a variety of sectors from agriculture to manufacturing to the sex trade . [33] However, other studies found that purdah still plays a significant role in women’s decisions to participate in the workforce, often prohibiting them from taking opportunities they would otherwise. [34] The degree to which women observe purdah and the pressures they face to conform or to earn income vary with their socioeconomic class.

Political participation

Social and mobility restrictions under purdah severely limit women's involvement in political decision making in government institutions and in the judiciary . [35] Lack of mobility and discouragement from participating in political life means women cannot easily exercise their right to vote, run for political office, participate in trade unions, or participate in community level decision-making . [36]. Women’s limited participation in political decision-making therefore results in policies that do not sufficiently address needs and rights of women in areas such as access to healthcare, education and employment opportunities, property ownership, justice, and others . [37] Gender imbalance in policy-making also reinforces institutionalization of gender disparities . [38]

Influences on Purdah

Governmental Policies on Purdah

In Tunisia and Turkey, religious veiling is banned in public schools, universities, and government buildings as a measure to discourage displays of political Islam or fundamentalism . [39] . [40] In western Europe, veiling is seen as symbol of Islamic presence, and movements to ban veils have stirred great controversy. For instance, since 2004 France has banned all overt religious symbols including the Muslim headscarf . [41]. In Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh where the word purdah is primarily used, the government has no policies either for or against veiling.

Women’s Movements

Women have been engaging in efforts to challenge the gender inequality resulting from purdah. For instance, women in Pakistan (mainly from the middle and upper-classes) organized trade unions and exercise their right to vote and influence decision making . [42] However, their opponents accuse these women of falling for the pernicious influence of Westernization and turning their backs on tradition. . [43]

Globalization and migration

Globalization and Muslim women returning from diasporas has influenced Pakistani women’s purdah practice in areas outside of religious significance. . [44] One major influence is the desire to be modern and keep up with latest fashion or refusal to do so as a source of autonomy and power . [45] Simultaneously, due to modernization in many urban areas, purdah and face-veiling are seen as unsophisticated and backwards, creating a trend in less strict observance of purdah . [46]

For Muslim South Asian diaspora living in secular non-Muslim communities such as Pakistani-Americans, attitudes about purdah have changed to be less strict. . [47] As it pertains to education and economic opportunities, these immigrant families hold less conservative views about purdah after moving to America; for the daughters who do choose to wear the veil, they usually do so out of their own volition as a connection to their Islamic roots and culture . [48]

Islamization

Nations such as Pakistan have been swinging to more conservative laws and policies that use rhetoric of following Islamic law, sometimes termed Islamization. [49] The ideology is reinforcing traditional culture, traditional women’s roles in the domestic sphere, and the need to protect women’s honor. The result is policies that reinforce cultural norms that limit female mobility in the public sphere, promotion of gender segregation, and institutionalization of gender disparities. [50]

Controversy around women’s agency

Purdah as protection

Some scholars argue that purdah was originally designed to protect women from being harassed and seen as sexual objects . [51] In contemporary times, some men and women still interpret the purdah as a way to protect women’s safety while moving in public sphere . [52] Observing purdah is also seen as a way to uphold women’s honor and virtuous conduct . [53] However, critics point out that this view engages victim-blaming and places the onus of preventing sexual assault on women rather than the perpetrators themselves.

Purdah as oppression

Purdah is often criticized as oppression of women by limiting female autonomy, freedom of movement, and access to resources such as education, employment, and political participation. [54] Some scholars such as P. Singh and Roy interpret purdah as a form of male domination in the public sphere, and an “eclipse of Muslim woman’s identity and individuality” . [55] According to scholars such as Elizabeth White, “purdah is an accommodation to and a means of perpetuating the perceived differences between the sexes: the male being self-reliant and aggressive, the female weak, irresponsible, and in need of protection” . [56] Geraldine Books writes “in both cases [of spatial separation and veiling], women are expected to sacrifice their comfort and freedom to service the requirements of male sexuality: either to repress or to stimulate the male sex urge”. [57]

When purdah is institutionalized into laws, it limits opportunity, autonomy, and agency in both private and public life . [58] The result is policies that reinforce cultural norms that limit female mobility in the public sphere, promotion of gender segregation, and institutionalization of gender disparities . [59]

Sometimes reactions to purdah adherence can become violent. For instance in 2001 in Srinagar, India, four young Muslim women were victimized by acid attacks for not veiling themselves in public; similar threats and attacks have occurred in Pakistan and Kashmir . [60]

Purdah as empowerment

The revival of purdah in modern times is sometimes perceived as a statement for progressive gender relations. Some women wear veils and head coverings as a symbol for protection and freedom of mobility. They perceive purdah as an empowerment tool, to exercise their rights to access public space for education and economic independence. For instance, in rural Bangladeshi villages, women who wear the burkha were found to have higher social participation, visibility, which overall contributes to an increase in women’s status . [61]

See Also

- Awrah

- Burqa

- Chador

- Dupatta

- Ghoonghat

- Hijab

- Hijab by country

- Sex segregation and Islam

- Women in Bangladesh

- Women in India

- Women in Islam

- Women in Pakistan

- Zenana

References

- ^ Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51

- ^ Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51

- ^ “Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah

- ^ Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51

- ^ Ahmed, Leila. ‘Women and the Advent of Islam.’ Women Living under Muslim Laws June 1989 - Mar. 1990, 7/8 : 5-15

- ^ “Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah

- ^ Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51

- ^ Engineer, Asghar Ali. (1980) The Origin and Development of Islam, Orient Longman, Bombay

- ^ Engineer, Asghar Ali. (1980) The Origin and Development of Islam, Orient Longman, Bombay

- ^ Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51

- ^ Mernissi, Fatima. (1993) Women and Islam, 1987 Trans. Mary Jo Lakeland, 1991, Kali for Women, New Delhi

- ^ Ahmed, Leila. ‘Women and the Advent of Islam.’ Women Living under Muslim Laws June 1989 - Mar. 1990, 7/8 : 5-15

- ^ “Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah

- ^ “Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah

- ^ “Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah

- ^ “Purdah (Islamic Custom) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 17, 2013. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483829/purdah

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51

- ^ Shaheed, F. “The Cultural Articulation of Patriarchy: Legal Systems, Islam and Women.” South Asia Bulletin 6, no. 1 (1986): 38–44.

- ^ Arnett, Susan. King's College History Department, "Purdah." Last modified 2001. Accessed March 18, 2013. http://departments.kings.edu/womens_history/purdah.html.

- ^ Veiling and the Seclusion of Women. US Library of Congress [1]

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Papanek, Hanna. “Purdah: Separate Worlds and Symbolic Shelter.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 15, no. 03 (1973): 289–325. doi:10.1017/S001041750000712X.

- ^ Papanek, Hanna. “Purdah: Separate Worlds and Symbolic Shelter.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 15, no. 03 (1973): 289–325. doi:10.1017/S001041750000712X.

- ^ Michael A. Koenig, Saifuddin Ahmed, Mian Bazle Hossain, and A. B. M. Khorshed Alam Mozumder. “Women’s Status and Domestic Violence in Rural Bangladesh: Individual- and Community-level Effects.” Demography 40, no. 2 (May 1, 2003): 269–288. doi:10.1353/dem.2003.0014.

- ^ Michael A. Koenig, Saifuddin Ahmed, Mian Bazle Hossain, and A. B. M. Khorshed Alam Mozumder. “Women’s Status and Domestic Violence in Rural Bangladesh: Individual- and Community-level Effects.” Demography 40, no. 2 (May 1, 2003): 269–288. doi:10.1353/dem.2003.0014.

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Kabeer, N. “Poverty, purdah and women’s survival strategies in rural Bangladesh.” (1990): 134–148.

- ^ Kabeer, N. “Poverty, purdah and women’s survival strategies in rural Bangladesh.” (1990): 134–148.

- ^ Amin, Sajeda. “The Poverty–Purdah Trap in Rural Bangladesh: Implications for Women’s Roles in the Family.” Development and Change 28, no. 2 (1997): 213–233. doi 10.1111/1467-7660.00041.

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Shaheed, F. “The Cultural Articulation of Patriarchy: Legal Systems, Islam and Women.” South Asia Bulletin 6, no. 1 (1986): 38–44.

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Turkey headscarf ruling condemned Al Jazeera English (07 June 2008). Retrieved on February 2013.

- ^ Abdelhadi, Magdi Tunisia attacked over headscarves, BBC News, September 26, 2006. Accessed February 2013.

- ^ French MPs back headscarf ban BBC News (BBC). Retrieved on 13 February 2009.

- ^ Shaheed, F. “The Cultural Articulation of Patriarchy: Legal Systems, Islam and Women.” South Asia Bulletin 6, no. 1 (1986): 38–44.

- ^ Shaheed, F. “The Cultural Articulation of Patriarchy: Legal Systems, Islam and Women.” South Asia Bulletin 6, no. 1 (1986): 38–44.

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Veiling and the Seclusion of Women. US Library of Congress [2]

- ^ Bokhari, Syeda Saba. “Attitudes of Migrant Pakistani-muslim Families Towards Purdah and the Education of Women in a Secular Environment.” Dissertation Abstracts International. Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 58, no. 01 (July 1997): 193–193.

- ^ Bokhari, Syeda Saba. “Attitudes of Migrant Pakistani-muslim Families Towards Purdah and the Education of Women in a Secular Environment.” Dissertation Abstracts International. Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 58, no. 01 (July 1997): 193–193.

- ^ Shahab, Rafi Ullah. (1993). Muslim Women in Political Power. Lahore: Maqbool Academy

- ^ Jalal, Ayesha (1991). The Convenience of Subservience: Women in the State of Pakistan. Kandiyoti, Deniz., Women, Islam and the State. Philadelphia: Temple University Press

- ^ Asha, S. “Narrative Discourses on Purdah in the Subcontinent.” ICFAI Journal of English Studies 3, no. 2 (June 2008): 41–51

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Engineer, Asghar Ali. (1980) The Origin and Development of Islam, Orient Longman, Bombay

- ^ Singh, Prahlad (2004). “Purdah: the seclusion of body and mind”. Abstracts of Sikh Studies, Vol 5, issue 1

- ^ White, Elizabeth H. “Purdah.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 2, no. 1 (April 1, 1977): 31–42. doi:10.2307/3346105

- ^ Brooks, Geraldine. Nine Parts of Desire: The Hidden World of Islamic Women. New York: Doubleday, 1995.

- ^ Haque, Riffat. “Gender and Nexus of Purdah Culture in Public Policy.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X) 25, no. 2 (July 2010): 303–310

- ^ Jalal, Ayesha (1991). The Convenience of Subservience: Women in the State of Pakistan. Kandiyoti, Deniz., Women, Islam and the State. Philadelphia: Temple University Press

- ^ Nelson, Dean. "Kashmir women ordered to cover up or risk acid attack." The Telegraph, , sec. World, August 13, 2012. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/india/9472909/Kashmir-women-ordered-to-cover-up-or-risk-acid-attack.html (accessed March 18, 2013).

- ^ Feldman, Shelley, and Florence McCarthy. "Purdah and Changing Patterns of Social Control among Rural Women in Bangladesh." Journal of Marriage and Family. 45. no. 4 (1983): 949-959. http://www.jstor.org/stable/351808 . (accessed February 17, 2013).