Rudra veena

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

Rudra veena | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Rudra vīnā, Been, Bin |

| Classification | String instrument |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 311.222 (True stick zither: instruments in which sound is produced by one or more vibrating strings, which consist solely of a string bearer or a string bearer with a resonator that is not integral to the instrument, with a string bearer shaped like a bar (bar zither), has a rigid and inflexible string carrier (stick zither), has no curved or flexible end (true stick zither), has more than one resonator gourds.) |

| Developed | By late 15th century |

| Musicians | |

| Asit Kumar Banerjee, Anant Bedekar, Bahauddin Dagar (b. 1970), Zia Mohiuddin Dagar (1929–1990), Mohammed Khan Faridi, Ustad Shamsuddin Faridi Desai (1936–2011), Zahid Faridi Desai, Hindraj Divekar (1954–2019), Jyoti Hegde, R.V. Hegde (b. 1953), Ustad Abid Hussain Khan, Ustad Asad Ali Khan (1937–2011), Bande Ali Khan (1826–1890), Jamaluddin Khan, Murad Khan, Naubat Khan, Omrao Khan, Rajab Ali Khan, Wazir Khan (Rampur), Zahid Khan, Krishnarao Kholapure, Sharada Mushti, Madhuvanti Pal (b. 1992), Dattatreya Rama Rao Parvatikar (1916–1990), Bindu Madhav Pathak (1935–2004), Shrikant Pathak, Peter Row (1944–2018), P.D. Shah (1911–1975), Carsten Wicke (b. 1970) | |

| Builders | |

| Kanailal & Brother, Kolkata | |

| More articles or information | |

| Veena, Saraswati veena, Vichitra veena, Chitra veena, Pinaka vina, Ālāpiṇī vīṇā | |

The Rudra veena (Sanskrit: रुद्र वीणा) (also spelled Rudraveena[1] or Rudra vīnā[2])—also called Bīn in North India[3]—is a large plucked string instrument used in Hindustani Music, especially dhrupad.[2] It is one of the major types of veena played in Indian classical music, notable for its deep bass resonance.[4]

The rudra veena is seen in temple architecture predating the Mughals. It is also mentioned in court records as early as the reign of Zain-ul Abidin (1418–1470),[3] and attained particular importance among Mughal court musicians.[3] Before Independence, rudra veena players, as dhrupad practitioners, were supported by the princely states; after Independence and the political integration of India, this traditional patronage system ended.[5] With the end of this traditional support, dhrupad's popularity in India declined, as did the popularity of the rudra veena.[5] However, in recent years, the rudra veena has seen a resurgence in popularity, driven at least partly by interest among non-Indian practitioners.[5][6]

Names and etymology

[edit]The name "rudra veena" comes from Rudra, a name for the Lord Shiva; rudra vina means "the veena of Shiva"[3] (compare Saraswati veena). According to oral tradition, Shiva created the rudra vina, with the two tumba resonator gourds, representing the breasts of either his wife Parvati or the goddess of arts and learning Saraswati, and the long dandi tube as the merudanda, both the human spine and the cosmic axis.[3] The length of the fretted area of the dandi is traditionally given as nine fists—the distance from the navel to the top of the skull.[3]

However it is strongly believed that Shiva created the rudra veena for the entertainment of the other gods as Shiva always enjoyed dancing and singing.

Another explanation is that the asura Ravana is said to have invented the rudra veena; inspired as he was with his devotion to Lord Shiva, or Rudra, he named the instrument Rudra veena. [citation needed]

The North Indian vernacular name "bīn" (sometimes written "bīṇ") is derived from the preexisting root "veena," the term generally used today to refer to a number of South Asian stringed instruments.[3] While the origins of "veena" are obscure, one possible derivation is from a pre-Aryan root meaning "bamboo" (possibly Dravidian, as in the Tamil veṟam, "cane," or South Indian bamboo flute, the venu), a reference to early stick or tube zithers[3]—as seen in the modern bīn, whose central dandi tube is still sometimes made from bamboo.[2]

Form and construction

[edit]The rudra veena is classified either as a stick zither[2] or tube zither[7][8] in the Sachs-Hornbostel classification system. The veena's body (dandi) is a tube of bamboo or teak between 137 and 158 cm (54 and 62 inches) long, attached to two large tumba resonators made from calabash gourds.[3][8] The tumbas on a rudra veena are around 34 to 37 cm (13 to 15 inches) in diameter; while veena players once attached tumbas to the dandi with leather thongs, modern instruments use brass screw tubes to attach the tumbas.[3]

Traditionally, the bottom end of the dandi, where the strings attach below the bridge (jawari), is finished with a peacock carving.[3] This peacock carving is hollow, to enhance the resonance of the instrument.[9] This hollow opens into the tube of the dandi, and is covered directly by the main jawari.[9] The other end of the instrument, holding most or all of the pegs, is finished with a carved makara.[9] Like the peacock at the other end and the dandi tube connecting them, the makara pegbox is also hollow.[9]

The rudra veena has twenty-one to twenty-four moveable frets (parda) on top of the dandi.[3][5][8] These frets are made of thin plates of brass with flat tops but curved wooden bases to match the shape of the dandi, each about two to four centimeters (0.75-1.5 inches) high.[3][6] While these frets were once attached to the instrument with wax, contemporary veena players use waxed flax ties to attach the frets.[8][4][3] This allows for players to adjust the frets to the individual microtones (shruti) of a raga.[8] By pulling the string up or down alongside the fret, the veena player can bend the pitch (meend) by as much as a fifth.[3]

A modern rudra veena has a total of seven or eight strings: four main melody strings, two or three chikari strings (which are used in rhythmic sections of the rag to delineate or emphasize the pulse, or taal), and one drone (laraj) string.[3][8] These strings are made of steel or bronze, and run from the pegs (and over the nut if coming from the pegbox) down to the peacock, passing over the jawari near the peacock.[9] A rudra veena will have three jawari; a main one covering an opening on the hollow peacock, and two smaller ones on the sides of the peacock, supporting the chikari and drone strings.[9] These jawari and other strings supports are traditionally made of Sambar stag antler; however, India has banned trade in Sambar deer antler since 1995, due to the deer's declining population and vulnerable status.[9][10] Strings are tuned by turning the ebony pegs to tighten or loosen the strings; the antler string supports can be moved for fine tuning.[9]

Unlike European stringed instruments, where strings are almost always tuned to the same notes on all instruments—a modern cello, for example, will usually have its open strings tuned to C2 (two octaves below middle C), followed by G2, D3, and then A3—the rudra veena follows Hindustani classical practice of a movable root note or tonic (moveable do). The four melody strings are tuned to the ma a fifth below the tonic; the tonic (sa); the pa a fifth above the tonic; and the sa an octave above the tonic.[3][4] Thus, if the lowest ma string was tuned to D2, then the four melody strings would be tuned to D2, A2, E3, and A3; if the lowest ma string was instead tuned to B♭1, then the four melody strings would be tuned to B♭1, F2, C3, and F3[3]

History

[edit]The rudra veena declined in popularity in part due to the introduction in the early 19th century of the surbahar, which allowed sitarists to more easily present the alap sections of slow dhrupad-style ragas. In the 20th century, Zia Mohiuddin Dagar modified and redesigned the rudra veena to use bigger gourds, a thicker tube (dandi), thicker steel playing strings (0.45-0.47 mm) and closed javari that. This produced a soft and deep sound when plucked without the use of any plectrum (mizrab). The instrument was further modified as the shruti veena by Lalmani Misra to establish Bharat's Shadja Gram and obtain the 22 shrutis.[11]

Gallery

[edit]-

Ca. 1605. Portrait of Naubat Khan by Ustad Mansur, Mughal School ca. 1605, British Museum, London.[12] The instrument is depicted with two strings.

-

Naubat Khan Kalawant playing a three-stringed rudra veena.

-

1690-1696 C.E. Man playing rudra veena

-

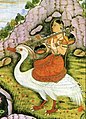

Ca. 1700. Saraswati riding a white bird and holding a northern style bīn (rudra vīnā). The instrument is depicted with four strings.

-

1808-1812. Illustration of a bīn, labeled "qaplious". At the time, the instrument illustrated was fretless; similar to the pinaka vina, it used a stick to slide on the string and choose notes.

-

1825. Miyan Himmat Khan Kalawant playing a bin, page from the Tasrih al-aqvam. The bin has four main strings that could be fretted and two side strings.

-

1891. A Bin Player, by William Gibb. The instrument depicted had four main strings that could be fretted and three side strings.

-

Bird on rudra veena, string holder.

-

Veena Maharaj Dattatreya Rama Rao Parvatikar (1916-1990) playing the Rudra veena

-

Ustad Asad Ali Khan playing the Rudra veena in traditional style

-

Video. A rudra veena or bīn is played by Mohi Baha'ud-din Dagar in dagarbani style.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Peddi, Sowjanya (26 November 2015). "Mastering the king of instruments". Thehindu.com. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Stick Zither with Gourd Resonators (Rudra Vina or Bin), Northern India, at the National Music Museum". Collections.nmmusd.org. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Dick, Alastair; Widdess, Richard; Bruguière, Philippe; Geekie, Gordon (29 October 2019), "Vīṇā", Grove Music Online, doi:10.1093/omo/9781561592630.013.90000347354, ISBN 9781561592630, retrieved 13 July 2021

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India - Arts Tribune". Tribuneindia.com. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Ustad Bahauddin Dagar interview: 'Dhrupad - flourishing branches, dwindling roots?'". Darbar.org. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ a b "What is the future of ancient rudra veena in Hindustani classical?". 17 October 2017.

- ^ Knight, Roderick. "The Knight Revision of Hornbostel-Sachs: a new look at musical instrument classification" (PDF). p. 23. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Brizard, Renaud (2018). Raga Yaman (Sleeve notes). Ustad Zia Mohiuddin Dagar. Ideologic Organ/Editions Mego.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Koch, Lars-Christian (direction). Rudra vina: der Bau eines nordindischen Saiteninstruments in der Tradition von Kanailal & Bros [Rudra veena: manufacturing of an Indian string instrument in the tradition of Kanailal & Bros] (DVD) (in English with German and English subtitles). Berlin: Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz. 2007. OCLC 662735435.

- ^ Timmins, R.J.; Kawanishi, K.; Giman, B.; Lynam, A.J.; Chan, B.; Steinmetz, R.; Baral, H. S.; Samba Kumar, N. (2015). "Rusa unicolor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T41790A85628124.

- ^ "Shruti Veena - Articles OMENAD". Omenad.net. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Bonnie C. Wade (January 1998). Imaging Sound: An Ethnomusicological Study of Music, Art, and Culture in Mughal India. University of Chicago Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-226-86841-7.

![Ca. 1605. Portrait of Naubat Khan by Ustad Mansur, Mughal School ca. 1605, British Museum, London.[12] The instrument is depicted with two strings.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2c/Work_of_Ustad_Mansur%2C_British_Museum.jpg/99px-Work_of_Ustad_Mansur%2C_British_Museum.jpg)