Santa Muerte

Santa Muerte | |

|---|---|

Close-up of a Santa Muerte south of Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas | |

| Lady Sebastienne, Lady of the Shadows, Lady of the Night, Lady of the Seven Powers, White Girl, Skinny Lady, Holy Death, Our Lady of the Holy Death | |

| Venerated in | Folk Catholicism, Mexico and the United States |

| Major shrine | Sanctuary of La Santísima Muerte and Enriqueta Romero, Mexico City Templo Santa Muerte Kansas Internacional |

| Feast | November 1, August 15 |

| Attributes | Human female skeleton clad in a robe, globe, scales of justice, hourglass, owls, scythe |

| Patronage | Homosexuals, bisexuals, transvestites, transsexuals, transgender people, lesbians, prostitutes, people in poverty, police officers, smugglers, drug dealers, taxi drivers, bar owners, bicycle messengers, love, prosperity, good health, fortune, healing, safe passage, protection against witchcraft, protection against assaults, protection against gun violence, protection against violent death |

Nuestra Señora de la Santa Muerte or, colloquially, Santa Muerte (Spanish for Holy Death or Sacred Death), is a female folk saint venerated primarily in Mexico and the Southwestern United States. A personification of death, she is associated with healing, protection, and safe delivery to the afterlife by her devotees.[1] Despite opposition by the Catholic Church, her cult arose from popular Mexican folk belief, a syncretism between indigenous Mesoamerican and Spanish Catholic beliefs and practices.

Since the pre-Columbian era Mexican culture has maintained a certain reverence towards death,[2] which can be seen in the widespread commemoration of the Day of the Dead.[3] Elements of that celebration include the use of skeletons to remind people of their mortality.[4] The worship of Santa Muerte is condemned by the Catholic Church in Mexico as invalid, but it is firmly entrenched among an increasing percentage of Mexican culture.[5][6]

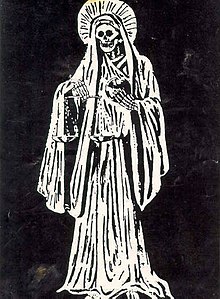

Santa Muerte generally appears as a female skeletal figure, clad in a long robe and holding one or more objects, usually a scythe and a globe.[7] Her robe can be of any color, as more specific images of the figure vary widely from devotee to devotee and according to the rite being performed or the petition being made.[8] As the worship of Santa Muerte was clandestine until the 20th century, most prayers and other rites have been traditionally performed privately in the home.[4]

Since the beginning of the 21st century, worship has become more public, especially in Mexico City after Enriqueta Romero initiated her famous Mexico City shrine in 2001.[4][9][10] The number of believers in Santa Muerte has grown over the past ten to twenty years, to several million followers in Mexico, the United States, and parts of Central America. Santa Muerte has similar male counterparts in the Americas, such as the skeletal folk saints San La Muerte of Argentina and Rey Pascual of Guatemala.[10]

Name and eponyms

The deity's Spanish name, Santa Muerte, which can be translated into English as either "Sacred Death" or "Holy Death", although religious studies scholar R. Andrew Chesnut believed that the former was a more accurate translation because it "better reveals" her identity as a folk saint.[11][5] A variant of this is Santísima Muerte, which is translated as "Most Holy Death" or "Most Saintly Death",[11] while devotees often call her Santisma Muerte during their rituals.[11]

Santa Muerte is also known by a wide variety of eponyms: the Skinny Lady (la flaquita),[12] the Bony Lady (la Huesuda),[12] the White Girl (la Niña Blanca),[13] the White Sister (la Hermana Blanca),[11] the Pretty Girl (la Niña Bonita),[14] the Powerful Lady (la Dama Poderosa),[14] and the Godmother (la Madrina).[13]

Santa Muerte is referred to by a number of names such as Señora de las Sombras ("Lady of the Shadows"), Señora Blanca ("White Lady"), Señora Negra ("Black Lady"), Niña Santa ("Holy Girl"), Santa Sebastiana (St. Sebastienne) or Doña Bella Sebastiana ("Our Beautiful Lady Sebastienne") and La Flaca ("The Skinny Woman").[15]

History

The precise origins of the worship of Santa Muerte are a matter of debate, but it is most likely a syncretism between Mesoamerican and Spanish Catholic beliefs.[5] Mesoamerica had always maintained a certain reverence towards death, which manifested itself among the religious practices of ancient Mexico, including in the Aztec religion. Death was personified in Aztec and other cultures in the form of humans with half their flesh missing, symbolizing the duality of life and death. From their ancestors the Aztecs inherited the gods Mictlantecuhtli and Mictecacihuatl, the lord and lady of Mictlan, the realm of those dead who died of natural causes. In order for the deceased to be accepted into Mictlan, offerings to the lord and lady of death were necessary. In European Christian tradition, many paintings employed skeletons to symbolize human mortality.[4]

According to INAH researcher Elsa Malvido Miranda, the worship of skeletal figures has precedent in Europe during times of epidemics. These skeletal figures would be dressed up as royalty with scepters and crowns, and be seated on thrones to symbolize the triumph of death.[16] In Latin America, the human skeleton was used to remind Catholics of the need for a "holy death," (muerte santa) fully confessed of sins. As relics, bones are also associated with certain saints, such as San Pascual Bailón in Guatemala and Chiapas.[4]

After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, the worship of death diminished but was never eradicated.[2] John Thompson of the University of Arizona's Southwest Center has found references dating to 18th-century Mexico. According to one account, recorded in the annals of the Spanish Inquisition, indigenous people in central Mexico tied up a skeletal figure, whom they addressed as "Santa Muerte," and threatened it with lashings if it did not perform miracles or grant their wishes.[10] Another syncretism between Pre-Columbian and Christian beliefs about death can be seen in Day of the Dead celebrations. During these celebrations, many Mexicans flock to cemeteries to sing and pray for friends and family members who have died. Children partake in the festivities by eating chocolate or candy in the shape of skulls.[3]

In contrast to the Day of the Dead, overt veneration of Santa Muerte remained clandestine until the middle of the 20th century. When it went public in sporadic occurrences, reaction was often harsh, and included the desecration of shrines and altars.[10] At the beginning of the 20th century, José Guadalupe Posada created a similar, but secular figure by the name of Catrina, a female skeleton dressed in fancy clothing of the period.[4] José Guadelupe Posada began to evoke the idea that the universality of death generated a fundamental equality amongst man. His paintings of skeletons in daily life and that La Catrina were meant to represent the arbitrary and violent nature of an unequal society.[17]

Modern artists began to reestablish Posada's styles as a national artistic objective to push the limits of upper-class tastes, like that of Diego Rivera's mural painting Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central with the image La Catrina. The image of the skeleton and the Day of the Dead ritual that used to be held underground became commercialized and domesticated. The skeletal images became that of folklore, encapsulating Posada's message of "la muerte igualidad" (equal death) in time.[17]

The skeletons were put in extravagant dresses with braids in their hair, altering the image of Posada's original La Catrina. As opposed to being the political message Posada intended, the skeletons of equality became skeletal images that were appealing to tourists and the national folkloric Mexican identity. In the past decade the regeneration of the social and political meaning and emergence of Doña Queta's statue has formed the Catholic cult of death, although not recognized by the Catholic Church.[17]

Veneration of Santa Muerte was documented in the 1940s in working-class neighborhoods in Mexico City, such as Tepito.[18] Other sources state that the revival has its origins around 1965 in the state of Hidalgo. At present Santa Muerte can be found throughout Mexico and also in parts of the United States and Central America.[10] There are videos, web sites, and music composed in honor of this religious expression.[4] The cult of Santa Muerte first came to widespread popular attention in Mexico in August 1998, when police arrested notorious gangster Daniel Arizmendi López and discovered a shrine to the saint in his home. Widely reported in the press, this discovery inspired the common association between Santa Muerte, violence, and criminality in Mexican popular consciousness.[19]

Since 2001, there has been a "meteoric growth" in the size of the Santa Muerte cult, largely due to her reputation for performing miracles.[14] Worship has been made up of roughly two million adherents, mostly in Mexico State, Guerrero, Veracruz, Tamaulipas, Campeche, Morelos, and Mexico City, with a recent spread to Nuevo León.[4] In the late 2000s, the founder of Mexico City's first Santa Muerte church, David Romo, estimated that there were around 5 million devotees in Mexico, constituting approximately 5% of the country's population.[20]

By the late 2000s Santa Muerte had become Mexico's second-most popular saint, after Saint Jude,[21] and had come to rival the country's "national patroness", the Virgin of Guadalupe.[14] The cult's rise was controversial, and in March 2009 the Mexican army demolished 40 roadside shrines near the U.S. border.[21] Circa 2005, the Santa Muerte cult was brought to the United States by Mexican and Central American migrants, and by 2012 had tens of thousands of followers throughout the country, primarily in cities with high Latino populations.[22]

Attributes and iconography

Santa Muerte is a personification of death.[23] Unlike other folk saints like Niño Fidencio and Pedro Batista is not seen as a dead human being herself.[23] To her devotees, she is associated with healing, protection, and ensuring a path to the afterlife.[11]

Some devotees consider Santa Muerte to be an eighth archangel. Still some other followers[who?], albeit a minority, believe that Santa Muerte is not a saint, since she has traits of jealousy and granting evil requests. These same followers state that she is not Satanic, but merely a fallen angel in purgatory trying to win back God's favor, and that is the reason she grants so many miracles.[24]

Although there are other death saints in Latin America, such as Argentina's San La Muerte, Santa Muerte is the only female saint of death in either South or North America.[11] Iconographically, Santa Muerte is a female adaptation of the Grim Reaper, typically being depicted as a skeletal figure wearing a shroud and carrying both a scythe and a globe.[23][2] Santa Muerte is marked out as female not by her figure but by her attire and hair. The latter was introduced by Enriqueta Romero.[14]

There are variations on the color of the cloak, and on what Santa Muerte holds in her hands. Interpretations of the color of her robe and accoutrements vary as well.[2] Images of Santa Muerte range from mass-produced articles sold in shops throughout Mexico and the U.S. to handcrafted effigies. Sizes vary immensely from small images held in one hand to those requiring a pickup truck to transport them. Some people have the image tattooed on their bodies.[5]

The two most common objects that Santa Muerte holds in her hands are a scythe and a globe. The scythe can symbolize the cutting of negative energies or influences. Also, as a harvesting tool, it can symbolize hope and prosperity.[8] Her scythe reflects her origins as the Grim Reapress ("la Parca" of medieval Spain),[10] and can represent the moment of death, when it is said to cut a silver thread. The scythe has a long handle, indicating that it can reach anywhere. The globe represents Death's dominion over the earth,[2] and can be seen as a kind of a tomb to which we all return. Having the world in her hand also symbolizes vast power.[8]

Other objects that can appear with an image of Santa Muerte include scales, an hourglass, an owl, and an oil lamp.[8] The scales allude to equity, justice, and impartiality, as well as divine will.[2] An hourglass indicates the time of life on earth. It also represents the belief that death is not the end, but rather the beginning of something new, as the hourglass can be turned to start over.[2] The hourglass denotes Santa Muerte's relationship with time as well as with the worlds above and below. It also symbolizes patience. An owl symbolizes her ability to navigate the darkness and her wisdom. The owl is also said to act as a messenger.[10] A lamp symbolizes intelligence and spirit, to light the way through the darkness of ignorance and doubt.[8]

Often, Santa Muerte stands near statues of Catholic images of Jesus Christ, the Virgin of Guadalupe, St. Peter, St. Jude, or St. Lazarus.[3] In the north of Mexico, Santa Muerte is venerated alongside Jesús Malverde, with altars containing both frequently found in drug busts.[25][26] However, some warn that Santa Muerte is very jealous and that her image should not be placed next to Catholic saints or there will be consequences.[3]

Veneration

Rites associated with the image

Rites dedicated to Santa Muerte are predicated on Catholic ones, including processions and prayers with the aim of gaining a favor.[9] Many believers in Santa Muerte are self-professed Catholics, who invoke the name of God the Father, Christ, the Holy Virgin, and St. Michael the Archangel in their petitions to Santa Muerte.[15] Altars contain an image of Santa Muerte, generally surrounded by any or all of the following: cigarettes; flowers; fruit; incense; water; alcoholic beverages; coins; candies; and candles.[2][9]

According to popular belief, Santa Muerte is very powerful and is reputed to grant many favors. These images, like those of Catholic saints, are treated as holy and can give favors in return for the faith of the believer, with miracles playing a vital role. In many ways, Santa Muerte acts like Catholic saints. As Señora de la Noche ("Lady of the Night"), she is often invoked by those exposed to the dangers of working at night, such as taxi drivers, bar owners, police, soldiers, and prostitutes. As such, devotees believe she can protect against assaults, accidents, gun violence, and all types of violent death.[27]

The image is dressed differently depending on what is being requested. Usually, the vestments of the image are differently colored robes, but it is also common for the image to be dressed as a bride (for those seeking a husband)[2] or even in a colonial-era nun's habit.[4] The colors of Saint Death votive candles and vestments are associated with the type of petitions made.[28]

White is the most common color and can symbolize gratitude, purity, or the cleansing of negative influences. Red is for love and passion. It can also signal emotional stability. The color gold signifies economic power, success, money, and prosperity. Green symbolizes justice, legal matters, or unity with loved ones. Amber or dark yellow indicates health. Images with this color can be seen in rehabilitation centers, especially those for drug addiction and alcoholism.[10]

Black represents total protection against black magic or sorcery, or conversely negative magic or for force directed against rivals and enemies. Blue candles and images of the saint indicate wisdom, which is favored by students and those in education. It can also be used to petition for health. Brown is used to invoke spirits from beyond while purple, like yellow, usually symbolizes health.[28]

Devotees may present her with a polychrome seven-color candle, which Chesnut believed was probably adopted from the seven powers candle of Santería, a syncretic faith brought to Mexico by Cuban migrants.[29] Here the seven colors are gold, silver, copper, blue, purple, red, and green.[2][8] In addition to the candles and vestments, each devotee adorns his or her own image in his or her own way, using U.S. dollars, gold coins, jewelry, and other items.[9]

Santa Muerte also has a "saint's day", which varies from shrine to shrine. The most prominent is November 1, when Enriqueta Romero celebrates hers at her historic Tepito shrine where the famous effigy is dressed as a bride.[15] Others celebrate her day on August 15.[2]

Places of worship

According to Chesnut, Santa Muerte's cult is "generally informal and unorganized".[14] Since worship of this image has been, and to a large extent still is, clandestine, most rituals are performed in altars constructed at the homes of devotees.[4] Recently shrines to this image have been mushrooming in public. The one on Dr. Vertiz Street in Colonia Doctores is unique in Mexico City because it features an image of Jesús Malverde along with Santa Muerte. Another public shrine is in a small park on Matamoros Street very close to Paseo de la Reforma.[10]

Shrines can also be found in the back of all kinds of stores and gas stations. As veneration of Santa Muerte becomes more accepted, stores specializing in religious articles, such as botánicas, are carrying more and more paraphernalia related to the cult. Historian R. Andrew Chesnut has discovered that many botanicas in both Mexico and the U.S. are kept in business by sales of Saint Death paraphernalia, with numerous shops earning up to half of their profits on Santa Muerte items.[10] This is true even of stores in very well known locations such as Pasaje Catedral behind the Mexico City Cathedral, which is mostly dedicated to store selling Catholic liturgical items. Her image is a staple in esoterica shops.[9]

There are those who now call themselves Santa Muerte priests or priestesses, such as Jackeline Rodríguez in Monterrey. She maintains a shop in Mercado Juárez in Monterrey, where tarot readers, curanderos, herbal healers and sorcerers can also be found.[30]

Sanctuary of La Santísima Muerte

The establishment of the first public sanctuary to the image began to change how Santa Muerte was venerated. The veneration has grown rapidly since then, and others have put their images on public display, as well.[4]

In 2001, a believer by the name of Enriqueta Romero Romero decided to take a life-sized image of Santa Muerte out of her home in Mexico City and build a shrine for it, visible from the street.[4] The shrine does not hold Catholic masses or occult rites, but people come here to pray and to leave offerings to the image.[15]

The effigy is dressed in different color garb depending on the season, with the Romero family changing the dress every first Monday of the month. Over the dress are large quantities of jewelry on her neck and arms, as well as pinned to her clothing. These are offerings that have been left to the image as well as the flowers, fruits (esp. apples) candles, toys, money, notes of thanks for prayers granted, cigarettes, and alcoholic beverages that surround it.[15]

Enriqueta considers herself the chaplain of the sanctuary, a role she says she inherited from her aunt, who began the practice in the family in 1962.[15] The shrine is located on 12 Alfarería Street in Tepito, Colonia Morelos. For many, this Santa Muerte is the patron saint of Tepito.[18] The house also contains a shop that sells amulets, bracelets, medallions, books, images, and other items, but the most popular item is votive candles.[9]

On the first day of every month Enriqueta or one of her sons lead prayers and the saying of the Santa Muerte rosary, which lasts for about an hour and is based on the Catholic rosary.[9][10] On the first of November the anniversary of the altar to Santa Muerte constructed by Enriqueta Romero is celebrated. The Santa Muerte of Tepito is dressed as a bride and wears hundreds of pieces of gold jewelry given by the faithful to show gratitude for favors received, or to ask for one.[18]

The celebration officially begins at the stroke of midnight of November 1. About 5,000 faithful turn out to pray the rosary. For purification, instead of incense there is the smoke of marijuana. Flowers, pan de muerto, sweets, and candy skulls among other things can be seen. Food such as cake, chicken with mole, hot chocolate, coffee, and atole are served. Mariachis and marimba bands play.[18]

Iglesia Católica Tradicional México-Estados Unidos

The Iglesia Católica Tradicional México-Estados Unidos, Misioneros del Sagrado Corazón y San Felipe de Jesús ("Mexican-US Traditional Catholic Church, Missionaries of the Sacred Heart and Saint Philip of Jesus") is based in a house that has been converted for veneration purposes, located on Nicolás Bravo Street 35 in Colonia Morelos, closer to Metro Candelaria than to Tepito. Attendees here tend to be people from the neighborhood and include the very young and the very old who are predominantly female.[28] The sanctuary here contains a cross, an Archangel Michael and the Virgin of Guadalupe as well as Santa Muerte, on the main altar adorned with flowers.[9]

The church publishes a magazine called Devoción a la Santa Muerte ("Devotion to Santa Muerte") which reports testimony of devotees and news associated with the faith. This magazine has a circulation of about 25,000 in Mexico. Events sponsored by this organization include processions with the image from Tepito to the Zócalo, both as an act of faith and of defiance.[9]

In 2005, the organization lost its official government registration as a religious association. According to the Ministry of the Interior, this occurred because the organization had not informed the government of changes in the organization’s doctrine.[4] The government claims that the church changed its focus from traditional Catholicism to the worship of Santa Muerte, violating Article 29 of the Law of Religious Associations.[2] However, the Law of Religious Association and Public Worship does not state that such changes merit sanction.[4] The government claims their official status was withdrawn in order to protect the public.[2]

After its recognition was withdrawn, devotees took to the streets with their images and marched to the Zócalo, Los Pinos and the offices of the Interior Ministry to protest. After this protest, a new version of Santa Muerte appeared, called the Ángel de la Santa Muerte. A petition to reregister the organization was made in 2006 but the organization was told this would not be possible for another five years. However, under Mexican law, they can still operate without official recognition.[9] In January, 2011, the self-proclaimed archbishop of the church, David Romo was arrested and charged with belonging to a kidnapping ring in Mexico City. In June, 2012, Romo was sentenced to 66 years in prison and ordered to pay a fine of 666 times the Mexican minimum wage for the crimes of robbery, kidnapping and extortion.[31]

Sociology of the cult

The cult of Santa Muerte is present throughout the strata of Mexican society, although the majority of devotees are from the urban working class.[32] Most are young people, aged in their teens, twenties, or thirties, and are also mostly female.[33] A large following developed among Mexicans who are disillusioned with the dominant, institutional Catholic Church and, in particular, with the inability of established Catholic saints to deliver them from poverty.[5]

The phenomenon is based among people with scarce resources, excluded from the formal market economy, as well as the judicial and educational systems, primarily in the inner cities and the very rural areas.[2] Devotion to Santa Muerte is what anthropologists call a "cult of crisis". Devotion to the image peaks during economic and social hardships, which tend to affect the working classes more. Santa Muerte tends to attract those in extremely difficult or hopeless situations but also appeals to smaller sectors of middle class professionals and even the affluent.[4][28] Some of her most devoted followers are those individuals associated with petty economic crimes, committed often out of desperation; such as prostitutes, pickpockets and thieves.[2]

The worship of Santa Muerte also attracts those who are not inclined to seek the traditional Catholic Church for spiritual solace, as it is part of the "legitimate" sector of society. Many followers of Santa Muerte live on the margins of the law or outside it entirely. Many street vendors, taxi drivers, vendors of counterfeit merchandise, street people, prostitutes, pickpockets, petty drug traffickers and gang members are not practicing Catholics or Protestants, but neither are they atheists.[2]

In essence they have created their own new religion that reflects their realities, identity, and practices, especially since it speaks to the violence and struggles for life that many of these people face.[2] Conversely both police and military in Mexico can be counted among the faithful who ask for blessings on their weapons and ammunition.[2]

While worship is largely based in poor neighborhoods, Santa Muerte is also venerated in affluent areas such as Mexico City's Condesa and Coyoacán districts.[16] However, negative media coverage of the worship and condemnation by the Catholic Church in Mexico and certain Protestant denominations have influenced public perception of the cult of Saint Death. With the exception of some artists and politicians, some of whom perform rituals secretly, those in higher socioeconomic strata look upon the veneration with distaste as a form of superstition.[4]

Association with the LGBT community

Santa Muerte is also seen as a protector of homosexual, bisexual, and transgender communities in Mexico,[34] since many are considered to be outcast from society.[35] Many LGBT people ask her for protection from violence, hatred, disease, and to help them in search of love.[36][37]

Her intercession is commonly invoked in same-sex marriage ceremonies performed in Mexico.[38][39] The Iglesia Católica Tradicional México-Estados Unidos, also known as the Church of Saint Death, recognizes gay marriage and performs religious wedding ceremonies for homosexual couples.[40][41][42][43]

Association with criminality

In the Mexican and U.S. press, the Santa Muerte cult is often associated with violence, criminality, and the illegal drug trade.[44] She is a popular deity in prisons, both among inmates and staff, and shrines dedicated to her can be found in many cells.[45][16][46] The majority of believers are poor people who are not necessarily criminals, but the public belief in her by several drug traffickers and small numbers of other petty criminals has indirectly associated her with crime, especially low-level organized crime.[18]

In Mexico, authorities have linked the worship of Santa Muerte to prostitution, drug trafficking, kidnapping, smuggling, and homicides.[2][5][15] Criminals, among her most fervent believers, are likely to pray to her for successful completion of a job as well as escaping from the police or jail. In the north of Mexico, she is venerated along with Jesús Malverde, the so-called "Saint of Drug Traffickers". Malverde's following is strong, especially in his hometown of Sinaloa, but the symbol of Santa Muerte is much more aggressive.[47]

Altars with images of Santa Muerte have been found in many drug houses in both Mexico and the United States.[2] Among Santa Muerte's more famous devotees are kidnapper Daniel Arizmendi López, known as El Mochaorejas, and Gilberto García Mena, one of the bosses of the Gulf Cartel.[16][46] In March 2012, the Sonora State Investigative Police announced that they had arrested eight people for murder for allegedly having performed a human sacrifice of a woman and two ten-year-old boys to Santa Muerte (see: Silvia Meraz).[48]

In December 2010, the self-acclaimed bishop David Romo was arrested on charges of banking funds of a kidnapping gang linked to a cartel. He continues to lead his sect from his prison, but it is unfeasible for Romo or anyone else to gain dominance over the Santa Muerte cult. Her faith is spreading rapidly and "organically" from town to town, so that is easy to become a preacher or messianic figure. Drug lords, like that of La Familia Cartel, take advantage of "gangster foot soldiers'" vulnerability and enforced religious obedience to establish a holy meaning to their cause that would keep their soldiers disciplined.[47]

Votive candles

Santa Muerte is a multifaceted saint, with various symbolic meanings and her devotees can call upon her a wide range of reasons. In herbal shops and markets one can find a plethora of Santa Muerte paraphernalia like the votive candles that have her image on the front and in a color representative of its purpose. On the back of the candles are prayers associated with the color's meaning and may sometimes come with additional prayer cards.[49]

The candles are placed on altars and devotees turn to specific colored candles depending on their circumstance. Some keep the full range of colored candle while others focus on one aspect Santa Muerte's spirit. Santa Muerte's image as satanic or evil has been derived from her association with drug trafficking and the dead bodies found at her altar, however, the specific colors for the candles indicate that Santa Muerte's devotees stem from many walks of life beyond crime, violence, and the drug trade. Santa Muerte is called upon for matters of the heart, health, money, wisdom, and justice. There is the brown candle of wisdom, the white candle of gratitude and consecration, the black candle for protection and vengeance, the red candle of love and passion, the gold candle for monetary affairs, the green candle for crime and justice, the purple candle for healing.[50]

The black votive candle is lit for prayer in order to implore La Flaca's protection and vengeance. It is the lowest selling candle due to its association with "black magic" and witchcraft. It is not regularly seen at devotional sites, and is usually kept and lit in the privacy of one's home. To avert from calling upon official Catholic saints for illegal purpose, drug trafficker will light Santa Muerte's black candle to ensure protection of shipment of drugs across the border.[50]

Black candles are presented to Santa Muerte's altars that drug traffickers used to ensure protection from violence of rival gangs as well as ensure harm to their enemies in gangs and law enforcement. As the drug war in Mexico escalates, Santa Muerte's veneration by drug bosses increases and her image is seen again and again in various drug houses. Ironically, the military and police officers that are employed to dismantle the White Lady's shrines make up a large portion of her devotees. Furthermore, even though her presence in the drug world is becoming routine, the sale of black candles pales in comparison to top selling white, red, and gold candles.[51]

One of Santa Muerte's more popular uses is in matters of the heart. The red candle that symbolizes love is helpful in various situations having to do with love. Her initial main purpose was in that of love magic during the colonial era in Mexico, which may have been derived from the love magic being brought over from Europe. Her origins are still unclear but it is possible that the image of the European Grim Reaper combined with the indigenous celebrations of death are at the root of La Flaca's existence, in so that the use of love magic in Europe and that of pre-Columbian times that was also merging during colonization may have established the saint as manipulator of love.[52]

The majority of anthropological writing on Santa Muerte discuss her significance as provider of love magic and miracles.[10] The candle can be lit for Santa Muerte to attract a certain lover and ensure their love. In contrast though, the red candle can be prayed to for help in ending a bad relationship in order to start another one. These love miracles require specific rituals to increase their love doctors power. The rituals require several ingredients including red roses and rose water for passion, binding stick to unite the lovers, cinnamon for prosperity, and several others depending on the specific ritual.[10]

Santa Muerte and the Catholic Church

The Vatican has condemned the cult of Santa Muerte in Mexico as blasphemous, calling it a "degeneration of religion".[53] Mexico's Catholic Church has accused Santa Muerte devotees of mixing Christianity with devil-worshiping cultism.[5] The Catholic Church has linked Santa Muerte to Satanist practices, saying she is being used to mislead desperate people.[3]

They state that Santa Muerte is an idol, the worship of which has been rejected by God in the Old Testament. Veneration of this or any other idol can be a form of inadvertent devil-worship, because regardless of the intent of the worshipers; the devil can trick people into doing such things. Priests regularly chastise parishioners, telling them that death is not a person but rather a phase of life.[4] However, the Church stops short of labeling such followers as heretics, instead accusing them of heterodoxy.[54]

Another reason the Mexican Catholic Church condemns worship of Santa Muerte is that most of her rites are based on Catholic liturgy.[2] It is felt that at best the worship of a "Saint of Holy Death" is a misinterpretation of Catholic doctrine. A holy death or muerte santa means that the deceased has had the benefits of being spiritually prepared for death via the sacraments and confession, but the concept is not personified.[54] Another reason is that some of its devotees eventually split from the Mexican Catholic Church and began vying for control of those same buildings.[5] Some Mexican Catholic and Protestant churches both view the worship of the saint of death as a kind of cult of black magic that should be condemned as trickery.[4] The majority of devotees of Santa Muerte, however, do not worry about any contradiction between the church and the worship of Santa Muerte.[2]

Santa Muerte in the United States

The Santa Muerte cult established itself in the United States circa 2005, brought to the country by Mexican and Central American migrants.[33] By 2012, Chesnut suggested that there were tens of thousands of devotees in the U.S.,[55] This cult is primarily visible in cities with high populations, such as New York City, Chicago, Houston, San Antonio, Tucson, and Los Angeles,[3][5] although it has also been located in cities with small Latino communities like Richmond, Virginia.[56] There are fifteen religious groups dedicated to her in Los Angeles alone,[2] which include the Temple of Santa Muerte.[57]

In some places, such as Northern California and New Orleans, her popularity has spread beyond the Latino community. For instance, The Santisima Muerte Chapel of Perpetual Pilgrimage is maintained by a woman of Danish descent, while The New Orleans Chapel of the Santisima Muerte was founded in 2012 by a European-American devotee.[58][59]

As in Mexico, some elements of the Catholic Church in the United States are trying to combat Santa Muerte worship, especially in Chicago.[3][5][60][61] But compared to the Catholic Church in Mexico, the official reaction in the U.S. is mostly either non-existent or muted. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has not issued an official position on this relatively new phenomenon in the country.[5] Opposition to the veneration of Saint Death took an unprecedented violent turn in late January, 2013, when vandal(s) smashed a controversial statue of the folk saint, which had appeared in the San Benito, Texas, municipal cemetery at the beginning of the month.[62]

Popular culture

- In the documentary La Santa Muerte, Mexican filmmaker Eva Aridjis explores the origins of the cult and takes us on a tour of the altars, prisons and neighborhoods in Mexico City where some of the saint's most devoted followers can be found.

- In the Criminal Minds Season 5 episode "Rite of Passage", Santa Muerte is mentioned several times, and appears as a painting on a barn.

- In Dexter, Santa Muerte is featured as prominently involved in a case that Miami Metro - Homicide Division is working on throughout Season 5.

- The Breaking Bad episode "No Más" opens with two Mexican cartel hit men crawling to a statue of Santa Muerte to pray for assistance in their mission to kill Walter White.

- In American Horror Story: Coven, Sarah Paulson's name card in the opening sequence shows Santa Muerte, also known as the Lady of the Seven Powers, to foreshadow that Paulson's character Cordelia would perform the seven wonders and become the next supreme witch in the season finale.

- In American Horror Story: Hotel, Episode 10 "She Gets Revenge", John Lowe goes to a temple dedicated to the "Lady of the Shadows", where he kills several worshippers and takes their ears as part of the chamber collection.

- In Paranormal Activity: The Marked Ones, the apartment has various Santa Muerte statues and in a botánica, there are many statues and a large wall mural of a winged Santa Muerte with a crown, hourglass and a globe. The official poster shows Santa Muerte in prayer.

- In the True Detective Season 2 episode "The Western Book of the Dead," a Santa Muerte statue is kept inside the city manager's home.

- The 2014 movie "The Book of Life" features a major character named La Muerte, who shows many similarities to Santa Muerte and whose physical appearance is based on La Calavera Catrina.

See also

- Azrael

- Blasphemy

- Día de los Muertos

- Death deity

- Death (personification)

- Heresy

- La Calavera Catrina

- Maximón, Contemporary Mayan worship, Guatemala.

- Psychopomp

- Shinigami

- Skull art

References

- ^ Chesnut 2012, pp. 6–7. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Araujo Peña, Sandra Alejandro; Barbosa Ramírez Marisela; Galván Falcón Susana; García Ortiz Aurea; Uribe Ordaz Carlos. "El culto a la Santa Muerte: un estudio descriptivo". Revista Psichologia (in Spanish). Mexico City: Universidad de Londres. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Ramirez, Margaret. "'Saint Death' comes to Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Garma, Carlos (2009-04-10). "El culto a la Santa Muerte" (in Spanish). Mexico City: El Universal. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gray, Steven (2007-10-16). "Santa Muerte: The New God in Town". Time.com. Chicago: Time. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- ^ Vatican in a Bind About Santa Muerte

- ^ "Los Angeles believers in La Santa Muerte say they aren't a cult | The Madeleine Brand Show | 89.3 KPCC". 66.226.4.226. 2012-01-10. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ^ a b c d e f Velazquez, Oriana (2007). El libro de la Santa Muerte (in Spanish). Mexico City: Editores Mexicanos Unidos, S.A. pp. 13–18. ISBN 978-968-15-2040-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Villarreal, Hector (2009-04-05). "La Guerra Santa de la Santa Muerte". Milenio semana (in Spanish). Mexico City: Milenio. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint, R. Andrew Chesnut, OUP, 2012

- ^ a b c d e f Chesnut 2012, p. 7. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ a b Chesnut 2012, p. 3. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ a b Chesnut 2012, p. 5. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ a b c d e f Chesnut 2012, p. 8. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ a b c d e f g Velazquez, Oriana (2007). El libro de la Santa Muerte (in Spanish). Mexico City: Editores Mexicanos Unidos, S.A. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-968-15-2040-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Pacheco Colín, Ricardo. "El culto a la Santa Muerte pasa de Tepito a Coyoacán y la Condesa". La Cronica de Hoy (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Fragoso, Perla. "De la "calavera domada" a la subversión santificada. La Santa Muerte, un nuevo imaginario religioso en México".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e "La Santa Muerte de Tepito cumple seis años" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Radio Trece. Archived from the original on 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Chesnut 2012, pp. 15–16. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ Chesnut 2012, pp. 8–9. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ a b Chesnut 2012, p. 4. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ Chesnut 2012, pp. 9–11. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ a b c Chesnut 2012, p. 6. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ Ramirez, Margaret (2007-09-30). "'Saint Death' comes to Chicago". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "El culto a la Santísima Muerte, un boom en México". terra (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Santa Muerte: The Extraordinary Devotion To Mexico's Saint Of Death (PHOTOS)". Huffington Post. 2012-03-08.

- ^ Velazquez, Oriana (2007). El libro de la Santa Muerte (in Spanish). Mexico City: Editores Mexicanos Unidos, S.A. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-968-15-2040-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "World Religions & Spirituality | Cronica De La Santa Muerte". Has.vcu.edu. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ^ Chesnut 2012, pp. 19–20, 26. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ Harden Cooper, Ricardo (2008-02-14). "Vende bien aquí la Santa Muerte". El Porvenir (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Dan 66 aĂąos de cĂĄrcel a lĂder de la Santa Muerte - DF". El Universal. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ^ Chesnut 2012, pp. 11–12. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ a b Chesnut 2012, p. 13. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ "Archives". outinthebay.com. Out In The Bay. 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-04-24.

- ^ "Redux: A Catholic Saint and an Aztec God". The Last Word On Nothing. 2012-04-11. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ^ "Santa Muerte is no saint, say Mexican bishops". Speroforum.com. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ^ Comments Leave a Comment Categories Santa Muerte (2011-05-19). "Santa Muerte « bonemojo". Bonemojo.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ^ "Iglesia de Santa Muerte casa a gays - El Universal - Sociedad". El Universal. 2010-03-03. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ^ (MÉXICO) SOCIEDAD-SALUD > AREA: Asuntos sociales. "La Iglesia de Santa Muerte mexicana celebró su primera boda gay y prevé 9 más - ABC.es - Noticias Agencias". ABC.es. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ los21com on Martes, enero 24, 2012 (2012-01-24). "La Nueva Iglesia De La Santa Muerte Permite Bodas Gay". Los21.com. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "La Santa Muerte celebra "bodas homosexuales" en México - México y Tradición" (in Spanish). Mexicoytradicion.over-blog.org. 2010-06-02. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ^ "Culto a la santa muerte casará a gays". Tendenciagay.com. 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ^ "Mexico's Holy Death Church Will Conduct Gay Weddings". Ross Institute. 2010-01-07. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ^ Chesnut 2012, pp. 10, 14. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ Chesnut 2012, pp. 14–15. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ a b Chesnut, R. Andrew; Borealis, Sarah (2012-02-20). Santa Muerte - Cronica de la Santa Muerte - Santa Muerte Timeline. World Religions & Spirituality Project VCU, Virginia Commonwealth University, 20 January 2012. Retrieved from http://www.has.vcu.edu/wrs/profiles/SantaMuerte.htm.

- ^ a b Grillo, Ioan (2011). El Narco. Bloomsbury Press.

- ^ CNN Wire Staff (2012-03-30). "Officials: 3 killed as human sacrifices in Mexico". CNN.com. CNN. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Thompson, John (Winter 1998). "Santísma Muerte: Origin and Development of a Mexican Occult Image". Journal of the Southwest. 40 (4).

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Chesnut, R. Andrew (2012). Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint. Oxford University Press, Inc. pp. 3–27.

- ^ Chesnut, Andrew (2012). Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint. Oxford University Press. pp. 102, 103.

- ^ Thompson, John (Winter 1998). "Santísma Muerte: Origin and Development of a Mexican Occult Image". Journal of the Southwest. 40 (4).

- ^ "BBC News - Vatican declares Mexican Death Saint blasphemous". Bbc.co.uk. 2013-05-09. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ^ a b Garcia Meza, Daniel (2008-11-01). "La "Niña blanca" mejor conocida como La Santa Muerte". El Siglo de Torreon (in Spanish). Torreon, Mexico. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Chesnut 2012, p. 11. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ Chesnut 2012. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChesnut2012 (help)

- ^ "Templo a la Santa Muerte". Archived from the original on 2009-05-22. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- ^ "Santisima Muerte Chapel of Perpetual Pilgrimage". Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ "The New Orleans Chapel of the Santisima Muerte". Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ^ Martin, Michelle (2012-02-19). "Our Lady of Guadalupe battles 'Holy Death' for devotion of Mexican faithful". Our Sunday Visitor. Archived from the original on 2012-02-17.

- ^ Lorentzen, Lois Ann (2009-05-28). "Holy Death on the US/Mexico Border". The University of Chicago Divinity School.

- ^ Rodriguez, Michael; Jimenez, Francisco E. (2013-01-25). Q&A – Occult experts weigh in on Saint Death's 'desecration'. San Benito News, 25 January 2013. Retrieved from http://news.yahoo.com/q-occult-experts-weigh-saint-015947105.html.

Bibliography

- Aridjis, Homero. La Santa Muerte (Alfaguara, Mexico, 2004)

- D'Angelo Mauro. Oracion de la Santisima Muerte (Sole Nero Edizioni, 2007)

- Lorusso, Fabrizio. Santa Muerte. Patrona dell'umanità (Stampa Alternativa/Nuovi Equilibri, 2013) ISBN 9788862223300

- Chesnut, R. Andrew. Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint (Oxford University Press, 2012) ISBN 0199764654

External links

- [1] La Santa Muerte, Full length documentary about Santa Muerte, Spanish, English subtitles.

- Santa Muerte: Inspired and Ritualistic Killings FBI

- Santa Muerte Web Page with selected materials in Spanish, English and Italian

- Dr. R. Andrew Chesnut Research Activities

- Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint, Dr. R. Andrew Chesnut's book talk at the Library of Congress

- Authorities in the northern Mexican state of Sonora have arrested eight people accused of killing two boys and one woman as human sacrifices for Santa Muerte -- the saint of death

- Leovy J (2009-12-07). Santa Muerte in L.A.: A gentler vision of 'Holy Death'. Los Angeles Times, viewed 2009-12-07.

- Santa Muerte a photo essay from Mexico City

- World Religions & Spirituality Project | Santa Muerte

- Cronica de la Santa Muerte

- Santa Muerte: Mexico's Devotion to The Saint of Death

- Santa Muerte: The Skeleton Saint's Deadly American Debut

- Santa Muerte: A Familiar Death

- I Call Her La Flaca

- Santa Muerte and Black Magic Murder on the Border

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZgQftFWM41Q

- "La Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint article on Atlas Obscura

- Nuestra Santisima Muerte A documentary online

- Angels in Christianity

- Archangels

- Christianity and death

- Christian folklore

- Christianity in Mexico

- Christianity in the United States

- Christianity and syncretic religions

- Culture in Mexico City

- Death goddesses

- Demons in Christianity

- Fictional skeletons

- Folk saints

- Fortune goddesses

- Homosexuality and Catholicism

- Illegal drug trade in Mexico

- LGBT culture in Mexico

- LGBT Hispanic and Latino American culture

- Mexican folklore

- North American deities

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Religion in Mexico

- Religion in the United States

- Religiously motivated violence in Mexico

- Roman Catholic Church in the United States

- Roman Catholic Church in Mexico

- Wonderworkers

- Superstitions of Mexico

- Syncretism

- Vengeance goddesses

- Individual angels