Scopes trial

| Tennessee v. Scopes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | Criminal Court of Tennessee |

| Full case name | The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes |

| Decided | July 21, 1925 |

| Citation | None |

| Case history | |

| Subsequent action | Scopes v. State (1926) |

| Court membership | |

| Judge sitting | John T. Raulston |

The Scopes Trial, formally known as The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes and commonly referred to as the Scopes Monkey Trial, was an American legal case in 1925 in which a substitute high school teacher, John Scopes, was accused of violating Tennessee's Butler Act, which had made it unlawful to teach human evolution in any state-funded school.[1] The trial was deliberately staged to attract publicity to the small town of Dayton, Tennessee, where it was held. Scopes was unsure whether he had ever actually taught evolution, but he purposely incriminated himself so that the case could have a defendant.

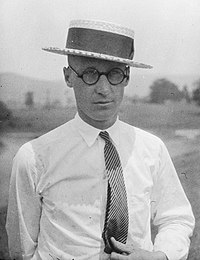

Scopes was found guilty and fined $100 (equivalent to $1,737 in 2023), but the verdict was overturned on a technicality. The trial served its purpose of drawing intense national publicity, as national reporters flocked to Dayton to cover the big-name lawyers who had agreed to represent each side. William Jennings Bryan, three-time presidential candidate, argued for the prosecution, while Clarence Darrow, the famed defense attorney, spoke for Scopes. The trial publicized the Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy, which set Modernists, who said evolution was not inconsistent with religion,[2] against Fundamentalists, who said the word of God as revealed in the Bible took priority over all human knowledge. The case was thus seen as both a theological contest and a trial on whether "modern science" should be taught in schools.

Origins

−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

State Representative John W. Butler, a Tennessee farmer and head of the World Christian Fundamentals Association, lobbied state legislatures to pass anti-evolution laws. He succeeded when the Butler Act was passed in Tennessee, on March 25, 1925.[3] Butler later stated, "I didn't know anything about evolution... I'd read in the papers that boys and girls were coming home from school and telling their fathers and mothers that the Bible was all nonsense." Tennessee governor Austin Peay signed the law to gain support among rural legislators, but believed the law would neither be enforced nor interfere with education in Tennessee schools.[4] William Jennings Bryan thanked Peay enthusiastically for the bill: "The Christian parents of the state owe you a debt of gratitude for saving their children from the poisonous influence of an unproven hypothesis."[5]

In response, the American Civil Liberties Union financed a test case in which John Scopes, a Tennessee high school science teacher, agreed to be tried for violating the Act. Scopes, who had substituted for the regular biology teacher, was charged on May 5, 1925, with teaching evolution from a chapter in George William Hunter's textbook, Civic Biology: Presented in Problems (1914), which described the theory of evolution, race, and eugenics. The two sides brought in the biggest legal names in the nation, William Jennings Bryan for the prosecution and Clarence Darrow for the defense, and the trial was followed on radio transmissions throughout America.[6][7]

Dayton

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) offered to defend anyone accused of teaching the theory of evolution in defiance of the Butler Act. On April 5, 1925, George Rappleyea, local manager for the Cumberland Coal and Iron Company, arranged a meeting with county superintendent of schools Walter White and local attorney Sue K. Hicks at Robinson's Drug Store, convincing them that the controversy of such a trial would give Dayton much needed publicity. According to Robinson, Rappleyea said, "As it is, the law is not enforced. If you win, it will be enforced. If I win, the law will be repealed. We're game, aren't we?" The men then summoned 24-year-old John T. Scopes, a Dayton high school science and math teacher. The group asked Scopes to admit to teaching the theory of evolution.[8][9]

Rappleyea pointed out that, while the Butler Act prohibited the teaching of the theory of evolution, the state required teachers to use a textbook that explicitly described and endorsed the theory of evolution, and that teachers were, therefore, effectively required to break the law.[10] Scopes mentioned that while he couldn't remember whether he had actually taught evolution in class, he had, however, gone through the evolution chart and chapter with the class. Scopes added to the group: "If you can prove that I've taught evolution and that I can qualify as a defendant, then I'll be willing to stand trial."[11]

Scopes urged students to testify against him and coached them in their answers.[12] He was indicted on May 25, after three students testified against him at the grand jury; one student afterwards told reporters, "I believe in part of evolution, but I don't believe in the monkey business."[13] Judge John T. Raulston accelerated the convening of the grand jury and "... all but instructed the grand jury to indict Scopes, despite the meager evidence against him and the widely reported stories questioning whether the willing defendant had ever taught evolution in the classroom".[14] Scopes was charged with having taught from the chapter on evolution to an April 24, 1925, high-school class in violation of the Butler Act and nominally arrested, though he was never actually detained. Paul Patterson, owner of The Baltimore Sun, put up $500 in bail for Scopes.[15][16]

The original prosecutors were Herbert E. and Sue K. Hicks, two brothers who were local attorneys and friends of Scopes, but the prosecution was ultimately led by Tom Stewart, a graduate of Cumberland School of Law, who later became a U.S. Senator. Stewart was aided by Dayton attorney Gordon McKenzie, who supported the anti-evolution bill on religious grounds, and described evolution as "detrimental to our morality" and an assault on "the very citadel of our Christian religion".[17]

Hoping to attract major press coverage, George Rappleyea went so far as to write to the British novelist H. G. Wells asking him to join the defense team. Wells replied that he had no legal training in Britain, let alone in America, and declined the offer. John R. Neal, a law school professor from Knoxville, announced that he would act as Scopes' attorney whether Scopes liked it or not, and he became the nominal head of the defense team.[citation needed]

Baptist pastor William Bell Riley, the founder and president of the World Christian Fundamentals Association, was instrumental in calling lawyer and three-time Democratic presidential nominee, former United States Secretary of State, and lifelong Presbyterian William Jennings Bryan to act as that organization's counsel. Bryan had originally been invited by Sue Hicks to become an associate of the prosecution and Bryan had readily accepted, despite the fact he had not tried a case in thirty-six years. As Scopes pointed out to James Presley in the book Center of the Storm, on which the two collaborated: "After [Bryan] was accepted by the state as a special prosecutor in the case, there was never any hope of containing the controversy within the bounds of constitutionality."[18][19]

In response, the defense sought out Clarence Darrow, an agnostic. Darrow originally declined, fearing that his presence would create a circus atmosphere, but eventually realized that the trial would be a circus with or without him, and agreed to lend his services to the defense, later stating that he "realized there was no limit to the mischief that might be accomplished unless the country was aroused to the evil at hand".[20] After many changes back and forth, the defense team consisted of Darrow, ACLU attorney Arthur Garfield Hays, and Dudley Field Malone, an international divorce lawyer who had worked at the State Department.[citation needed]

The prosecution team was led by Tom Stewart, district attorney for the 18th Circuit (and future United States Senator), and included, in addition to Herbert and Sue Hicks, Ben B. McKenzie and William Jennings Bryan.[citation needed]

The trial was covered by famous journalists from the South and around the world, including H. L. Mencken for The Baltimore Sun, which was also paying part of the defense's expenses. It was Mencken who provided the trial with its most colorful labels such as the "Monkey Trial" of "the infidel Scopes". It was also the first United States trial to be broadcast on national radio.[21]

Proceedings

The ACLU had originally intended to oppose the Butler Act on the grounds that it violated the teacher's individual rights and academic freedom, and was therefore unconstitutional. Principally because of Clarence Darrow, this strategy changed as the trial progressed. The earliest argument proposed by the defense once the trial had begun was that there was actually no conflict between evolution and the creation account in the Bible; later, this viewpoint would be called theistic evolution. In support of this claim, they brought in eight experts on evolution. But other than Dr. Maynard Metcalf, a zoologist from Johns Hopkins University, the judge would not allow these experts to testify in person. Instead, they were allowed to submit written statements so that their evidence could be used at the appeal. In response to this decision, Darrow made a sarcastic comment to Judge Raulston (as he often did throughout the trial) on how he had been agreeable only on the prosecution's suggestions. Darrow apologized the next day, keeping himself from being found in contempt of court.[22]

The presiding judge, John T. Raulston, was accused of being biased towards the prosecution and frequently clashed with Darrow. At the outset of the trial, Raulston quoted Genesis and the Butler Act. He also warned the jury not to judge the merit of the law (which would become the focus of the trial) but on the violation of the act, which he called a 'high misdemeanor.' The jury foreman himself was unconvinced of the merit of the Act but he acted, as did most of the jury, on the instructions of the judge.[23]

By the later stages of the trial, Clarence Darrow had largely abandoned the ACLU's original strategy and attacked the literal interpretation of the Bible as well as Bryan's limited knowledge of other religions and science. Only when the case went to appeal did the defense return to the original claim that the prosecution was invalid because the law was essentially designed to benefit a particular religious group, which would be unconstitutional.[citation needed]

Bryan chastised evolution for teaching children that humans were but one of (precisely) 35,000 types of mammals and bemoaned the notion that human beings were descended "Not even from American monkeys, but from old world monkeys".[24]

Malone responded for the defense in a speech that was universally considered the oratorical triumph of the trial.[25] Arousing fears of "inquisitions", Malone argued that the Bible should be preserved in the realm of theology and morality and not put into a course of science. In his conclusion, Malone declared that Bryan's "duel to the death" against evolution should not be made one-sided by a court ruling that took away the chief witnesses for the defense. Malone promised that there would be no duel because "there is never a duel with the truth." The courtroom went wild when Malone finished, and Scopes declared Malone's speech to be the dramatic highpoint of the entire trial and insisted that part of the reason Bryan wanted to go on the stand was to regain some of his tarnished glory.[26]

On the sixth day of the trial, the defense ran out of witnesses. The judge declared that all of the defense testimony on the Bible was irrelevant and should not be presented to the jury (which had been excluded during the defense). During the court proceedings (7th day of the trial) the defense asked the judge to call Bryan as a witness to question him on the Bible, as their own experts had been rendered irrelevant; Darrow had planned the day before and called Bryan a "Bible expert". This move surprised those present in the court, as Bryan was a counsel for the prosecution and Bryan himself (according to a journalist reporting the trial) never made a claim of being an expert; although he did tout his knowledge of the Bible.[27] This testimony revolved around several questions regarding biblical stories and Bryan's beliefs (as shown below), this testimony culminated in Bryan declaring that Darrow was using the court to "slur the Bible" while Darrow replied that Bryan's statements on the Bible were "foolish".[28]

Examination of Bryan

On the seventh day of the trial, Clarence Darrow took the unorthodox step of calling William Jennings Bryan, counsel for the prosecution, to the stand as a witness in an effort to demonstrate that belief in the historicity of the Bible and its many accounts of miracles was unreasonable. Bryan accepted, on the understanding that Darrow would in turn submit to questioning by Bryan. Although Hays would claim in his autobiography that the cross-examination of Bryan was unplanned, Darrow spent the night before in preparation. The scientists the defense had brought to Dayton—and Charles Francis Potter, a modernist minister who had engaged in a series of public debates on evolution with the fundamentalist preacher John Roach Straton[citation needed]—prepared topics and questions for Darrow to address to Bryan on the witness stand.[29] Kirtley Mather, chairman of the geology department at Harvard and also a devout Baptist, played Bryan and answered questions as he believed Bryan would.[30][31] Raulston had adjourned court to the stand on the courthouse lawn, ostensibly because he was "afraid of the building" with so many spectators crammed into the courtroom, but probably because of the stifling heat (p. 227; Scopes and Presley p. 164).

Adam and Eve

An area of questioning involved the book of Genesis, including questions such as if Eve was actually created from Adam's rib, where did Cain get his wife, and how many people lived in Ancient Egypt. Darrow used these examples to suggest that the stories of the Bible could not be scientific and should not be used in teaching science with Darrow telling Bryan, "You insult every man of science and learning in the world because he does not believe in your fool religion."[32] Bryan's declaration in response was, "The reason I am answering is not for the benefit of the superior court. It is to keep these gentlemen from saying I was afraid to meet them and let them question me, and I want the Christian world to know that any atheist, agnostic, unbeliever, can question me anytime as to my belief in God, and I will answer him."[33]

Stewart objected for the prosecution, demanding to know the legal purpose of Darrow's questioning. Bryan, gauging the effect the session was having, snapped that its purpose was "to cast ridicule on everybody who believes in the Bible". Darrow, with equal vehemence, retorted, "We have the purpose of preventing bigots and ignoramuses from controlling the education of the United States." (p. 299)

A few more questions followed in the charged open-air courtroom. Darrow asked where Cain got his wife; Bryan answered that he would "leave the agnostics to hunt for her" (pp. 302–03). When Darrow addressed the issue of the temptation of Eve by the serpent, Bryan insisted that the Bible be quoted verbatim rather than allowing Darrow to paraphrase it in his own terms. However, after another angry exchange, Judge Raulston banged his gavel, adjourning the court.[citation needed]

End of the Trial

The confrontation between Bryan and Darrow lasted approximately two hours on the afternoon of the seventh day of the trial. It is likely that it would have continued the following morning but for Judge Raulston's announcement that he considered the whole examination irrelevant to the case and his decision that it should be "expunged" from the record. Thus Bryan was denied the chance to cross-examine the defense lawyers in return, although after the trial Bryan would distribute nine questions to the press to bring out Darrow's "religious attitude." The questions and Darrow's short answers were published in newspapers the day after the trial ended, with The New York Times characterizing Darrow as answering Bryan's questions "with his agnostic's creed, 'I don't know,' except where he could deny them with his belief in natural, immutable law."[34]

After the defense's final attempt to present evidence was denied, Darrow asked the judge to bring in the jury only to have them come to a guilty verdict:

We claim that the defendant is not guilty, but as the court has excluded any testimony, except as to the one issue as to whether he taught that man descended from a lower order of animals, and we cannot contradict that testimony, there is no logical thing to come except that the jury find a verdict that we may carry to the higher court, purely as a matter of proper procedure. We do not think it is fair to the court or counsel on the other side to waste a lot of time when we know this is the inevitable result and probably the best result for the case.

After they were brought in, Darrow then addressed the jury, telling them that:

We came down here to offer evidence in this case and the court has held under the law that the evidence we had is not admissible, so all we can do is to take an exception and carry it to a higher court to see whether the evidence is admissible or not...we cannot even explain to you that we think you should return a verdict of not guilty. We do not see how you could. We do not ask it.

Darrow closed the case for the defense without a final summation. Under Tennessee law, when the defense waived its right to make a closing speech, the prosecution was also barred from summing up its case.

Scopes never testified since there was never a factual issue as to whether he had taught evolution. Scopes later admitted that, in reality, he was unsure of whether he had taught evolution (another reason the defense did not want him to testify), but the point was not contested at the trial (Scopes 1967: pp. 59–60).

William Jennings Bryan's summation of the Scopes trial (distributed to reporters but not read in court):

"Science is a magnificent force, but it is not a teacher of morals. It can perfect machinery, but it adds no moral restraints to protect society from the misuse of the machine. It can also build gigantic intellectual ships, but it constructs no moral rudders for the control of storm-tossed human vessel. It not only fails to supply the spiritual element needed but some of its unproven hypotheses rob the ship of its compass and thus endanger its cargo. In war, science has proven itself an evil genius; it has made war more terrible than it ever was before. Man used to be content to slaughter his fellowmen on a single plane, the earth's surface. Science has taught him to go down into the water and shoot up from below and to go up into the clouds and shoot down from above, thus making the battlefield three times as bloody as it was before; but science does not teach brotherly love. Science has made war so hellish that civilization was about to commit suicide; and now we are told that newly discovered instruments of destruction will make the cruelties of the late war seem trivial in comparison with the cruelties of wars that may come in the future. If civilization is to be saved from the wreckage threatened by intelligence not consecrated by love, it must be saved by the moral code of the meek and lowly Nazarene. His teachings, and His teachings alone, can solve the problems that vex the heart and perplex the world."[35]

After eight days of trial, it took the jury only nine minutes to deliberate. Scopes was found guilty on July 21 and ordered to pay a US$100 fine (approximately $1,700 in present day terms when adjusted from 1925 for inflation).[36] Raulston imposed the fine before Scopes was given an opportunity to say anything about why the court should not impose punishment upon him and after Neal brought the error to the judge's attention the defendant spoke for the first and only time in court:

Your honor, I feel that I have been convicted of violating an unjust statute. I will continue in the future, as I have in the past, to oppose this law in any way I can. Any other action would be in violation of my ideal of academic freedom—that is, to teach the truth as guaranteed in our constitution, of personal and religious freedom. I think the fine is unjust. (World's Most Famous Court Trial, p. 313.)

Bryan died suddenly five days after the trial's conclusion.[37] The connection between the trial and his death is still debated.

Appeal to Supreme Court of Tennessee

Scopes' lawyers appealed, challenging the conviction on several grounds.

First, they argued that the statute was overly vague because it prohibited the teaching of "evolution," a very broad term. The court rejected that argument, holding:

Evolution, like prohibition, is a broad term. In recent bickering, however, evolution has been understood to mean the theory which holds that man has developed from some pre-existing lower type. This is the popular significance of evolution, just as the popular significance of prohibition is prohibition of the traffic in intoxicating liquors. It was in that sense that evolution was used in this act. It is in this sense that the word will be used in this opinion, unless the context otherwise indicates. It is only to the theory of the evolution of man from a lower type that the act before us was intended to apply, and much of the discussion we have heard is beside this case.

Second, the lawyers argued that the statute violated Scopes' constitutional right to free speech because it prohibited him from teaching evolution. The court rejected this argument, holding that the state was permitted to regulate his speech as an employee of the state:

He was an employee of the state of Tennessee or of a municipal agency of the state. He was under contract with the state to work in an institution of the state. He had no right or privilege to serve the state except upon such terms as the state prescribed. His liberty, his privilege, his immunity to teach and proclaim the theory of evolution, elsewhere than in the service of the state, was in no wise touched by this law.

Third, it was argued that the terms of the Butler Act violated the Tennessee State Constitution, which provided that "It shall be the duty of the General Assembly in all future periods of this government, to cherish literature and science." The argument was that the theory of the descent of man from a lower order of animals was now established by the preponderance of scientific thought, and that the prohibition of the teaching of such theory was a violation of the legislative duty to cherish science.

The court rejected this argument (Scopes v. State, 154 Tenn. 105, 1927), holding that the determination of what laws cherished science was an issue for the legislature, not the judiciary:

The courts cannot sit in judgment on such acts of the Legislature or its agents and determine whether or not the omission or addition of a particular course of study tends "to cherish science."

Fourth, the defense lawyers argued that the statute violated the provisions of the Tennessee Constitution that prohibited the establishment of a state religion. The Religious Preference provisions of the Tennessee Constitution (section 3 of article 1) stated, "no preference shall ever be given, by law, to any religious establishment or mode of worship."[38]

Writing for the court, Chief Justice Grafton Green rejected this argument, holding that the Tennessee Religious Preference clause was designed to prevent the establishment of a state religion as had been the experience in England and Scotland at the writing of the Constitution, and held:

We are not able to see how the prohibition of teaching the theory that man has descended from a lower order of animals gives preference to any religious establishment or mode of worship. So far as we know, there is no religious establishment or organized body that has in its creed or confession of faith any article denying or affirming such a theory. So far as we know, the denial or affirmation of such a theory does not enter into any recognized mode of worship. Since this cause has been pending in this court, we have been favored, in addition to briefs of counsel and various amici curiae, with a multitude of resolutions, addresses, and communications from scientific bodies, religious factions, and individuals giving us the benefit of their views upon the theory of evolution. Examination of these contributions indicates that Protestants, Catholics, and Jews are divided among themselves in their beliefs, and that there is no unanimity among the members of any religious establishment as to this subject. Belief or unbelief in the theory of evolution is no more a characteristic of any religious establishment or mode of worship than is belief or unbelief in the wisdom of the prohibition laws. It would appear that members of the same churches quite generally disagree as to these things.

Further, the court held that while the statute forbade the teaching of evolution (as the court had defined it), it did not require the teaching of any other doctrine, so that it did not benefit any one religious doctrine or sect over the others.

Nevertheless, having found the statute to be constitutional, the court set aside the conviction on appeal because of a legal technicality: the jury should have decided the fine, not the judge, since under the state constitution, Tennessee judges could not at that time set fines above $50, and the Butler Act specified a minimum fine of $100.[7]

Justice Green added a totally unexpected recommendation:

The court is informed that the plaintiff in error is no longer in the service of the state. We see nothing to be gained by prolonging the life of this bizarre case. On the contrary, we think that the peace and dignity of the state, which all criminal prosecutions are brought to redress, will be the better conserved by the entry of a nolle prosequi herein. Such a course is suggested to the Attorney General.

Attorney General L.D. Smith immediately announced that he would not seek a retrial, while Scopes' lawyers offered angry comments on the stunning decision.[39]

In 1968, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Epperson v. Arkansas 393 U.S. 97 (1968) that such bans contravene the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment because their primary purpose is religious.[10] Tennessee had repealed the Butler Act the previous year.[40]

Aftermath of the Trial

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Religion versus science debate

The trial revealed a growing chasm in American Christianity and two ways of finding truth, one "biblical" and one "evolutionist".[41] Author David Goetz writes that the majority of Christians denounced evolution at the time.[41]

Author Mark Edwards contests the conventional view that in the wake of the Scopes trial, a humiliated fundamentalism retreated into the political and cultural background, a viewpoint evidenced in the movie Inherit the Wind (1960) and the majority of contemporary historical accounts. Rather, the cause of fundamentalism's retreat was the death of its leader, Bryan. Most fundamentalists saw the trial as a victory and not a defeat, but Bryan's death soon after created a leadership void that no other fundamentalist leader could fill. Bryan, unlike the other leaders, brought name recognition, respectability, and the ability to forge a broad-based coalition of fundamentalist and mainline religious groups to argue for the anti-evolutionist position.[42]

Anti-evolution movement

The trial escalated the political and legal conflict between strict creationists and scientists to influence the extent to which evolution would be taught as science in Arizona and California schools. Before the Dayton trial only the South Carolina, Oklahoma, and Kentucky legislatures had dealt with anti-evolution laws or riders to educational appropriations bills. [citation needed]

After Scopes was convicted, creationists throughout the United States sought similar anti-evolution laws for their states.[43]

By 1927, there were 13 states, both in the North and South, that considered some form of anti-evolution law. At least 41 bills or resolutions were introduced into the state legislatures, with some states facing the issue repeatedly. Nearly all of these efforts were rejected, but Mississippi and Arkansas did put anti-evolution laws on the books after the Scopes trial that would outlive the Butler Act.[44][45]

In the Southwest, anti-evolution crusaders included ministers R. S. Beal and Aubrey L. Moore in Arizona and members of the Creation Research Society in California. They sought to ban evolution as a topic for study in the schools or, failing that, to relegate it to the status of unproven hypothesis perhaps taught alongside the biblical version of creation. Educators, scientists, and other distinguished laymen favored evolution. This struggle occurred later in the Southwest than elsewhere and persisted through the Sputnik era after 1957 when it collapsed, as the national mood inspired increased trust in science in general and support for evolution in particular.[45][46]

The opponents of evolution made a transition from the anti-evolution crusade of the 1920s to the creation science movement of the 1960s. Despite some similarities between these two causes, the creation science movement represented a shift from overtly religious to covertly religious objections to evolutionary theory — sometimes described as a Wedge Strategy — raising what it claimed to be scientific evidence in support of a literal interpretation of the Bible. Creation science also differed in terms of popular leadership, rhetorical tone, and sectional focus. It lacked a prestigious leader like Bryan, utilized pseudoscientific rather than religious rhetoric,[47] and was a product of California and Michigan instead of the South.[47]

Teaching of science

The Scopes trial had both short- and long-term effects in the teaching of science in schools in the United States. Though often upheld as a blow for the fundamentalists in the form of waning public opinion, the victory was not complete.[48] Though the ACLU had taken on the trial as a cause, in the wake of Scopes' conviction, they were unable to find any volunteers to take on the Butler law and by 1932, the ACLU gave up.[49] The anti-evolutionary legislation was not challenged again until 1965 and in the meantime William Jennings Bryan's cause was taken up by a number of organizations including the Bryan Bible League and the Defenders of the Christian Faith.[49]

The immediate effects of the trial are evident in the high school biology texts used in the second half of the 1920s and the early 1930s. Textbook publishers paid close attention to the trial to gauge what the public wanted or would tolerate in biology textbooks.[50] Of the most widely used textbooks after the trial, only one included the word "evolution" in its index; the relevant page includes biblical quotations.[48] The fundamentalists' target slowly veered off evolution in the mid-1930s. As the anti-evolutionist movement died out, biology textbooks began to include the previously removed evolutionary theory.[49] This also corresponds to the emerging demand that science textbooks be written by scientists rather than educators or education specialists.[48]

In 1958 the National Defense Education Act was passed with the encouragement of many legislators who feared the United States education system was falling behind that of the Soviet Union. The act yielded textbooks, produced in cooperation with the American Institute of Biological Sciences, which stressed the importance of evolution as the unifying principle of biology.[49] The new educational regime was not unchallenged. The greatest backlash was in Texas where attacks were launched in sermons and in the press.[48] Complaints were lodged with the State Textbook Commission. However, in addition to federal support, a number of social trends had turned public discussion in favor of evolution. These included increased interest in improving public education, legal precedents separating religion and public education, and continued urbanization in the South. This led to a weakening of the backlash in Texas, as well as to the repeal of the Butler Law in Tennessee in 1967.[48]

Publicity and Drama

Publicity

Edward J. Larson, an historian who won the Pulitzer Prize for History for his book Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion (2004), notes: "Like so many archetypal American events, the trial itself began as a publicity stunt."[51] The press coverage of the "Monkey Trial" was overwhelming.[52] The front pages of newspapers like The New York Times were dominated by the case for days. More than 200 newspaper reporters from all parts of the country and two from London were in Dayton.[53] Twenty-two telegraphers sent out 165,000 words per day on the trial, over thousands of miles of telegraph wires hung for the purpose;[53] more words were transmitted to Britain about the Scopes trial than for any previous American event.[53] Trained chimpanzees performed on the courthouse lawn.[53] Chicago's WGN radio station broadcast the trial with announcer Quin Ryan via clear-channel broadcasting first on-the-scene coverage of the criminal trial. Two movie cameramen had their film flown out daily in a small plane from a specially prepared airstrip.

H.L. Mencken's trial reports were heavily slanted against the prosecution and the jury, which were "unanimously hot for Genesis." He mocked the town's inhabitants as "yokels" and "morons." He called Bryan a "buffoon" and his speeches "theologic bilge." In contrast, he called the defense "eloquent" and "magnificent." Even today, some American creationists, fighting in courts and state legislatures to demand that creationism be taught on an equal footing with evolution in the schools, have claimed that it was Mencken's trial reports in 1925 that turned public opinion against creationism.[54] The media's portrayal of Darrow's cross-examination of Bryan, and the play and movie Inherit the Wind (1960), caused millions of Americans to ridicule religious-based opposition to the theory of evolution.[55]

The trial also brought publicity to the town of Dayton, Tennessee, and was hatched as a publicity stunt.[52] From The Salem Republican, June 11, 1925:

The whole matter has assumed the portion of Dayton and her merchants endeavoring to secure a large amount of notoriety and publicity with an open question as whether Scopes is a party to the plot or not.

Court house

At the site of the trial, in a $1-million restoration of the Rhea County Courthouse in Dayton, completed in 1979, the second-floor courtroom was restored to its original appearance during the Scopes trial. A museum of trial events in its basement contains such memorabilia as the microphone used to broadcast the trial, trial records, photographs, and an audiovisual history. Every July, local people re-enact key moments in the courtroom.[56] In front of the courthouse stands a commemorative plaque erected by the Tennessee Historical Commission:

2B 23

THE SCOPES TRIAL Here, from July 10 to 21, 1925 John

Thomas Scopes, a County High School

teacher, was tried for teaching that

a man descended from a lower order

of animals in violation of a lately

passed state law. William Jennings

Bryan assisted the prosecution;

Clarence Darrow, Arthur Garfield

Hays, and Dudley Field Malone the

defense. Scopes was convicted.

Rhea County Courthouse was designated a National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service in 1976.[57] It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.[58]

Humor

Anticipating that Scopes would be found guilty, the press fitted the defendant for martyrdom and created an onslaught of ridicule, and hosts of cartoonists added their own portrayals to the attack. For example:

- American Experience has published a gallery of such cartoons,[59] and perhaps the greatest collection of cartoons available would be the 14 reprinted in L. Sprague de Camp's The Great Monkey Trial.[citation needed])

- TIME magazine's initial coverage of the trial focused on Dayton as "the fantastic cross between a circus and a holy war."

- Life adorned its masthead with monkeys reading books and proclaimed, "the whole matter is something to laugh about."[60]

- Both Literary Digest and the popular humor magazine Life (1890–1930) ran compilations of jokes and humorous observations garnered from newspapers around the country.[61]

Overwhelmingly, the butt of these jokes was the prosecution and those aligned with it: Bryan, the city of Dayton, the state of Tennessee, and the entire South, as well as fundamentalist Christians and anti-evolutionists. Rare exceptions were found in the Southern press, where the fact that Darrow had saved Leopold and Loeb from the death penalty continued to be a source of ugly humor. The most widespread form of this ridicule was directed at the inhabitants of Tennessee.[62] Life described Tennessee as "not up to date in its attitude to such things as evolution."[63] TIME related Bryan's arrival in town with the disparaging comment, "The populace, Bryan's to a moron, yowled a welcome."[64]

Attacks on Bryan were frequent and acidic: Life awarded him its "Brass Medal of the Fourth Class," for having "successfully demonstrated by the alchemy of ignorance hot air may be transmuted into gold, and that the Bible is infallibly inspired except where it differs with him on the question of wine, women, and wealth."[65] Papers across the country routinely dismissed the efforts of both sides in the trial, while the European press reacted to the entire affair with amused condescension.[citation needed]

Famously vituperative attacks came from journalist H. L. Mencken, whose syndicated columns from Dayton for The Baltimore Sun drew vivid caricatures of the "backward" local populace, referring to the people of Rhea County as "Babbits", "morons", "peasants", "hill-billies", "yaps", and "yokels". He chastised the "degraded nonsense which country preachers are ramming and hammering into yokel skulls". However, Mencken did enjoy certain aspects of Dayton, writing, "The town, I confess, greatly surprised me. I expected to find a squalid Southern village, with darkies snoozing on the horse-blocks, pigs rooting under the houses and the inhabitants full of hookworm and malaria. What I found was a country town full of charm and even beauty—a somewhat smallish but nevertheless very attractive Westminster or Balair." He described Rhea County as priding itself on a kind of tolerance or what he called "lack of Christian heat", opposed to outside ideas but without hating those who held them.[66] He pointed out, "The Klan has never got a foothold here, though it rages everywhere else in Tennessee."[67] Mencken attempted to perpetrate a hoax, distributing flyers for the "Rev. Elmer Chubb", but the claims that Chubb would drink poison and preach in lost languages were ignored as commonplace by the people of Dayton, and only the Commonweal bit.[68] Mencken continued to attack Bryan, including in his famously withering obituary of Bryan, "In Memoriam: W.J.B.", in which he charged Bryan with "insincerity"—not for his religious beliefs but for the inconsistent and contradictory positions he took on a number of political questions during his career.[69] Years later, Mencken did question whether dismissing Bryan "as a quack pure and unadulterated" was "really just".[70] Mencken's columns made the Dayton citizens irate and drew general fire from the Southern press.[71] After Raulston ruled against the admission of scientific testimony, Mencken left Dayton, declaring in his last dispatch, "All that remains of the great cause of the State of Tennessee against the infidel Scopes is the formal business of bumping off the defendant."[72] Consequently, the journalist missed Darrow's cross-examination of Bryan on Monday.

Cartoons

"Gallery: Monkey Trial". American Experience. PBS. A gallery of cartoons produced in reaction to the trial, from PBS' American Experience.

Stage and film

- Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee's play Inherit the Wind (1955), fictionalizes the 1925 Scopes "Monkey" Trial as a means to discuss the then-contemporary McCarthy trials. It portrays Darrow and Bryan as the characters named Henry Drummond and Matthew Brady.[73] The playwrights state in a note at the opening of the play that it is not meant to be a historical account,[74] and there are numerous instances where events were substantially altered or invented.[75][76] Despite the disclaimer in the play's preface, that states, while the trial was its "genesis", it is "not history",[77] Lawrence and Lee later said that it was written in response to McCarthyism and was chiefly about intellectual freedom.[78][79] and the fact that it deviates from actual events in many ways, the play has largely been accepted as history by the public.[76][80][81][82]

- Adaptations:

- Inherit the Wind was made into a 1960 film directed by Stanley Kramer, with Spencer Tracy as Drummond and Fredric March as Brady. Although there are numerous changes in the plot, they include more of the actual events recorded in the trial transcript, such as when Darrow implies the court is prejudiced, being cited for contempt of court for his comments and his subsequent statement of contrition that persuaded the judge to drop the charge.

- There has also been a trio of television versions, with Melvyn Douglas and Ed Begley in 1965, Jason Robards and Kirk Douglas in 1988, and Jack Lemmon and George C. Scott in 1999.

- Adaptations:

- Peter Goodchild's play, The Great Tennessee Monkey Trial (1993), was written based on original sources and transcripts from the Scopes trial, and aims to be historically accurate.[83] It was produced as part of L.A. Theatre Works’ Relativity Series, which features science-themed plays and receives major funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, which seeks "to enhance public understanding of science and technology in the modern world".[84] According to Audiofile Magazine, which pronounced this production the 2006 D.J.S. Winner of AudioFile Earphones Award: "Because there are no recordings of the actual trial, this production is certainly the next best thing."[85] BBC broadcast The Great Tennessee Monkey Trial in 2009, in a version starring Neil Patrick Harris and Ed Asner.[86]

- Gale Johnson's play Inherit the Truth (1987) was based on the original transcripts of the case.[87] Inherit the Truth was performed yearly during the Dayton Scopes Festival until it ended its run in 2009.[88] The play was written as a rebuttal to the 1955 play and the 1960 film, which local Daytons claim did not accurately depict the trial or William Jennings Bryan.[89] In 2007 Bryan College purchased the rights to the production and began work on a student film version of the film, which it viewed at that year's Scopes Festival.[90][91]

- The film Alleged (2011), a romantic drama set around the Scopes Trial, starring Brian Dennehy as Clarence Darrow and Fred Thompson as William Jennings Bryan, was released by Two Shoes Productions.[92] While the main storyline is fictional, all of the courtroom scenes are accurate to the actual trial transcript. Coincidentally, Dennehy had played Matthew Harrison Brady, the fictionalized counterpart of Bryan, in the 2007 Broadway revival of Inherit the Wind.

- In 2013, the Comedy Central series Drunk History retold portions of the trial.[93]

Literature

- Ronald Kidd's novel, Monkey Town: The Summer of the Scopes Trial (2006), set in summer 1925, in Dayton, Tennessee, is based on the Scopes Trial.[94]

Music

Multiple musical works were created about the trial, as well as in reaction to trial coverage. For example:

- "Monkey Music". American Experience. PBS. A series of folk songs produced in reaction to the trial, from PBS' American Experience, includes:

- "Bryan's Last Fight"

- "Can't Make a Monkey of Me"

- "Monkey Business"

- "Monkey Out of Me"

- "The John Scopes Trial"

- "There Ain't No Bugs"

- The International Novelty Orchestra with Billy Murray. "Monkey Biz-Ness (Down In Tennessee 1925)". Internet Archive (public domain ed.). is comedy song about the Scopes Monkey Trial.[95]

Non-fiction

- The Scopes trial did not appear in the Encyclopædia Britannica until 1957, when its inclusion was spurred by the successful run of Inherit the Wind on Broadway, which was mentioned in the citation.

- It was not until the 1960s that the Scopes trial began to be mentioned in the history textbooks of American high schools and colleges, usually as an example of the conflict between fundamentalists and modernists, and often in sections that also talked about the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the South.[96]

See also

References

- ^ "Tennesse Anti-evolution Statute – UMKC School of Law". umkc.edu.

- ^ Cotkin, George (2004) [1992]. Reluctant Modernism: American Thought and Culture, 1880–1900. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 7–14. ISBN 978-0-7425-3746-0. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ^ Ferenc M. Szasz, "William B. Riley and the Fight against Teaching of Evolution in Minnesota." Minnesota History 1969 41(5): 201-216.

- ^ Balmer, Randall (2007). Thy Kingdom Come. Basic Books.p.111

- ^ Larson 1997, p. 59

- ^ Edward J. Larson, Summer for the Gods: And America's Continuing Debate over Science And Religion (2006)

- ^ a b See Supreme Court of Tennessee John Thomas Scopes v. The State, at end of opinion filed January 17, 1927. The court did not address the question of how the assessment of the minimum possible statutory fine, when the defendant had been duly convicted, could possibly work any prejudice against the defendant.

- ^ "A Monkey on Tennessee's Back: The Scopes Trial in Dayton". Tennessee State Library and Archives. Retrieved 2011-11-13.

- ^ The Great Monkey Trial, by L. Sprague de Camp, Doubleday, 1968

- ^ a b An introduction to the John Scopes (Monkey) Trial by Douglas Linder. UMKC Law. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- ^ Presley, James and Scopes, John T. Center of the Storm. p. 60. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. (1967)

- ^ Larson 1997, p. 108 "Scopes had urged the students to testify against him, and coached them in their answers."

- ^ Larson 1997, p. 89,107

- ^ Larson 1997, p. 108

- ^ The New York Times May 26, 1925: pp. 1, 16

- ^ de Camp, pp. 81–86.

- ^ Larson 1997, p. 107

- ^ de Camp, pp. 72–74, 79

- ^ Scopes and Presley, Center of the Storm. pp. 66–67.

- ^ Larson 1997, p. 101

- ^ Clark, Constance Areson (2000). "Evolution for John Doe: Pictures, The Public, and the Scopes Trial Debate". Journal of American History. 87 (4): 1275–1303. JSTOR 2674729.

- ^ "Evolution in Tennessee". Outlook 140 (29 July 1925), pp. 443-44.

- ^ Larson, Edward J., Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion (1997), pp. 108-109. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press (1998).

- ^ Scopes, John Thomas (1971), The world's most famous court trial, State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes; complete stenographic report of the court test of the Tennessee anti-evolution act at Dayton, July 10 to 21, 1925, including speeches and arguments of attorneys, New York: Da Capo Press, pp. 174–78, ISBN 978-1-886363-31-1

- ^ de Camp, p335

- ^ Scopes and Presley, Center of the Storm, pp. 154–56.

- ^ de Camp, p.412.

- ^ Scopes, John Thomas (1971), The world's most famous court trial, State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes; complete stenographic report of the court test of the Tennessee anti-evolution act at Dayton, July 10 to 21, 1925, including speeches and arguments of attorneys, New York: Da Capo Press, p. 304, ISBN 978-1-886363-31-1

- ^ Arthur Garfield Hays, Let Freedom Ring (New York: Liveright, 1937), pp. 71–72; Charles Francis Potter, The Preacher and I (New York: Crown, 1951), pp. 275–76.

- ^ de Camp, pp. 364–65

- ^ Kirtley F. Mather, "Creation and Evolution", in Science Ponders Religion, ed. Harlow Shapley (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1960), pp. 32–45.

- ^ Moran, 2002, p. 150

- ^ Moran, 2002, p157

- ^ The New York Times, July 22, 1925: p. 2.

- ^ "Faith of Our Fathers". Beliefnet.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Kazin, M. A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan. Anchor Press (2007), p. 134. ISBN 0385720564.

- ^ The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution was not, at the time of the Scopes decision in the 1920s, deemed applicable to the states. Thus, Scopes' constitutional defense on establishment of religion grounds rested—and had to rest—solely on the state constitution, as there was no federal Establishment Clause protection available to him. See Court's opinion. See generally Incorporation doctrine and Everson v. Board of Education (seminal U.S. Supreme Court opinion finally applying the Establishment Clause against states in 1947).

- ^ The New York Times 16 January 1927: 1, 28.

- ^ "Butler Act Repeal – Tennessee House Bill No. 48 (1967)". todayinsci.com.

- ^ a b David Goetz, "The Monkey Trial". Christian History 1997 16(3): pp. 10-18. 0891-9666

- ^ Edwards (2000)

- ^ William V. Trollinger, God's Empire: William Bell Riley and Midwestern Fundamentalism (1991).

- ^ R. Halliburton, Jr., "The Adoption of Arkansas' Anti-Evolution Law," Arkansas Historical Quarterly 23 (Autumn 1964): 280

- ^ a b Christopher K. Curtis, "Mississippi's Anti-Evolution Law of 1926." Journal Of Mississippi History 1986 48(1): pp. 15-29.

- ^ George E. Webb, "The Evolution Controversy in Arizona and California: From the 1920s to the 1980s". Journal of the Southwest 1991 33(2): pp. 133-150. 0894-8410.

- ^ a b Gatewood (1969)

- ^ a b c d e Grabiner, J.V. & Miller, P.D., Effects of the Scopes Trial, Science, New Series, Vol. 185, No. 4154 (September 6, 1974), pp. 832-837

- ^ a b c d Moore, Randy, The American Biology Teacher, Vol. 60, No. 8 (Oct., 1998), pp. 568-577

- ^ Adam R. Shapiro, Trying Biology: The Scopes Trial, Textbooks, and the Antievolution Movement in American Schools (2013) excerpt and text search

- ^ Larson 2004, p. 211

- ^ a b Larson 2004, pp. 212–213

- ^ a b c d Larson 2004, p. 213

- ^ Harrison, S. L. (1994). "The Scopes 'Monkey Trial' Revisited: Mencken and the Editorial Art of Edmund Duffy". Journal of American Culture. 17 (4): 55–63. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.1994.t01-1-00055.x.

- ^ Larson 2004, p. 217

- ^ "Scopes Trial Museum". Tennessee History for Kids. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- ^ National Park Service (April 2007). "National Historic Landmarks Survey: List of National Historic Landmarks by State".

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Database and Research Page". National Register Information System. National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ^ "Gallery: Monkey Trial". American Experience. PBS. A gallery of cartoons produced in reaction to the trial, from PBS' American Experience.

- ^ E.S. Martin, Life 86 (July 16, 1925): p. 16.

- ^ "Life Lines", Life 85 (June 18, 1925): 10; 85 (June 25, 1925): 6, 86 (July 2, 1925): 8; 86 (July 9, 1925): 6; 86 (July 30, 1925): 6; "Life's Encyclopedia," Life 85 (July 25, 1925): 23; Kile Croak, "My School in Tennessee," Life 86 (July 2, 1925); 4; Arthur Guiterman, "Notes for a Tennessee Primer," Life 86 (July 16, 1925): 5; "Topics in Brief," Literary Digest, for 86 (July 4, 1925): 18; 86 (July 11, 1925): 15; 86 (July 18, 1925): 15; 86 (July 25, 1925): 15, 86 (August 1, 1925): 17; 86 (August 8, 1925): 13.

- ^ "Tennessee Goes Fundamentalist," New Republic 42 (April 29, 1925): pp. 258–60; Howard K. Hollister, "In Dayton, Tennessee," Nation 121 (July 8, 1925): pp. 61–62; Dixon Merritt, "Smoldering Fires," Outlook 140 (July 22, 1925): pp. 421–22.

- ^ Martin, Life 86 (July 16, 1925): p. 16.

- ^ "The Great Trial," Time 6 (July 20, 1926): p. 17.

- ^ Life 86 (July 9, 1925): p. 7.

- ^ Mencken, H.L., "Sickening Doubts About Value of Publicity", The Baltimore Evening Sun, July 9, 1925.

- ^ Edgar Kemler, The Irreverent Mr. Mencken (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1948), pp. 175–90. For excerpts from Mencken's reports see William Manchester, Sage of Baltimore: The Life and Riotous Times of H.L. Mencken (New York: Andrew-Melrose, 1952) pp. 143–45, and D-Days at Dayton: Reflections on the Scopes Trial, ed. Jerry R. Tompkins (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Univ. Press, 1965) pp. 35–51.

- ^ H.L. Mencken, Heathen Days, 1890–1936 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1943) pp. 231–34; Michael Williams, "Sunday in Dayton", Commonweal 2 (July 29, 1925): pp. 285–88.

- ^ "In Memoriam: W.J.B." was first printed in The Baltimore Evening Sun, July 27, 1925; rpt. by Mencken in the American Mercury 5 (October 1925) pp. 158–60 in his Prejudices (Fifth Series), pp. 64–74; and in https://archive.org/details/mencken017105mbp Cooke, Alistair, The Vintage Mencken, Vintage Books, pp. 161-167.

- ^ Mencken, Heathen Days, pp. 280–87.

- ^ "Mencken Epithets Rouse Dayton's Ire", The New York Times, July 17, 1925, 3.

- ^ "Battle Now Over, Mencken Sees; Genesis Triumphant and Ready for New Jousts", H.L. Mencken, The Baltimore Evening Sun, July 18, 1925, http://www.positiveatheism.org/hist/menck04.htm#SCOPES9, URL accessed April 27, 2008.

- ^ Notes on Inherit the Wind UMKC Law School. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- ^ "Inherit the Wind: The Playwrights' Note". xroads.virginia.edu.

- ^ "Inherit the Wind, Drama for Students". Gale Group. 1 January 1998. Retrieved 31 August 2012. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required)

- ^ a b Riley, Karen L.; Brown, Jennifer A.; Braswell, Ray (1 January 2007). "Historical Truth and Film: Inherit the Wind as an Appraisal of the American Teacher". American Educational History Journal. Retrieved 31 August 2012. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required)

- ^ "Inherit the Wind". virginia.edu.

- ^ Larson 1997, p. 240

- ^ Inherit the controversy

- ^ Benen, Steve (July 1, 2000). "Inherit the Myth?". Church and State. Retrieved August 31, 2012. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required)

- ^ Ronald L. Numbers, Darwinism Comes to America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998), p. 85, 86.

- ^ "Evolution of a Scholar". Pepperdine Law. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- ^ "The Great Tennessee Monkey Trial: Details". Worldcat. 2006. ISBN 9781580813525.

- ^ Goodchild, Peter (2006). The Great Tennessee Monkey Trial. L.A. Theatre Works. ISBN 9781580813525.

- ^ "The Great Tennessee Monkey Trial: AudioFile Review". AudioFile Magazine. Portland, ME. December 2006.

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00nwz36

- ^ 'Inherit the Wind' opens at the Springer Opera House Ledger-Enquirer

- ^ Play based on Scopes trial ending 20-year run Wate.com

- ^ Play based on Scopes trial ending 20-year run TimesNews.net

- ^ Scopes trial film begins July 14 Times Free Press

- ^ Associated Press. College plans own version of movie on evolution trial. Times Daily, July 7, 2007, p48

- ^ "Synopsis > Alleged". Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ^ "Comedy Central: Drunk History: Clip".

- ^ AudioFile Magazine. "The Great Tennessee Monkey Trial: Description". audiobooksync.com.

- ^ Mr. Fab. "Silly 78s: International Novelty Orchestra with Billy Murray "Monkey Biz-ness (Down in Tennessee)" [GOTTA have some Billy Murray in any survey of 78s- he was the early 20th century's biggest recording star, and certainly one of the most prolific]". Music For Maniacs.

- ^ Lawrance Bernabo and Celeste Michelle Condit (1990). "Two Stories of the Scopes Trial: Legal and Journalistic Articulations of the Legitimacy of Science and Religion" in Popular Trials: Rhetoric, Mass Media, and the Law, edited by Robert Hariman. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, pp. 82–83.

Bibliography

- de Camp, L. Sprague (1968), The Great Monkey Trial, Doubleday, ISBN 0-385-04625-1

- Clark, Constance Areson (2000), "Evolution for John Doe: Pictures, The Public, and the Scopes Trial Debate", Journal of American History, 87 (4): 1275–1303, ISSN 0021-8723, JSTOR 2674729

- Conkin, Paul K. (1998), When All the Gods Trembled: Darwinism, Scopes, and American Intellectuals, pp. 185 pp., ISBN 0-8476-9063-6

- Edwards, Mark (2000), "Rethinking the Failure of Fundamentalist Political Antievolutionism after 1925", Fides et Historia, 32 (2): 89–106, ISSN 0884-5379, PMID 17120377

- Folsom, Burton W., Jr. (1988), "The Scopes Trial Reconsidered", Continuity (12): 103–127, ISSN 0277-1446

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gatewood, Willard B., Jr., ed., ed. (1969), Controversy in the Twenties: Fundamentalism, Modernism, & Evolution

{{citation}}:|editor-first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Harding, Susan (1991), "Representing Fundamentalism: The Problem of the Repugnant Cultural Other", Social Research, 58 (2): 373–393

- Larson, Edward J. (1997), Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion, BasicBooks, ISBN 0-465-07509-6

- Larson, Edward J. (2004), Evolution, Modern Library, ISBN 0-679-64288-9

- Lienesch, Michael (2007), In the Beginning: Fundamentalism, the Scopes Trial, and the Making of the Antievolution Movement, University of North Carolina Press, pp. 350pp, ISBN 0-8078-3096-8

- Menefee, Samuel Pyeatt (2001), "Reaping the Whirlwind: A Scopes Trial Bibliography", Regent University Law Review, 13 (2): 571–595

- Moran, Jeffrey P. (2002), The Scopes Trial: A Brief History with Documents, Bedford/St. Martin's, pp. 240pp, ISBN 0-312-24919-5

- Moran, Jeffrey P. (2004), "The Scopes Trial and Southern Fundamentalism in Black and White: Race, Region, and Religion", Journal of Southern History, 70 (1): 95–120, doi:10.2307/27648313, JSTOR 27648313

- Shapiro, Adam R. Trying Biology: The Scopes Trial, Textbooks, and the Antievolution Movement in American Schools (2013) excerpt and text search

- Smout, Kary Doyle (1998), The Creation/Evolution Controversy: A Battle for Cultural Power, pp. 210 pp, ISBN 0-275-96262-8

- Scopes, John T.; Presley, James (June 1967), Center of the Storm: Memoirs of John T. Scopes, Henry Holt & Company, ISBN 0-03-060340-4

- Tompkins, Jerry R. (1968), D-Days at Dayton: Reflections on the Scopes Trial, Louisiana State University Press, OCLC 411836

Further reading

- Cline, Austin. "Atheism: Scopes Monkey Trial". About.com.

- Ginger, Ray. Six Days or Forever?: Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes. London: OUP, 1974 [1958].

- Haldeman-Julius, Marcet. "Impressions of the Scopes Trial." Haldeman-Julius Monthly, vol. 2.4 (Sept. 1925), pp. 323–347 (excerpt - included in "Clarence Darrow's Two Great Trials (1927). Haldeman-Julius was an eye-witness and a friend of Darrow’s.

- Lamb, Brian (June 28, 1998). "Interview with Edward Larson about Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion". Booknotes. WBGH.

- Larson, Edward John. Summer for the Gods: the Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion. New York: Basic Books, 1997.

- McKay, Casey Scott (2013). "Tactics, Strategies, & Battles – Oh My!: Perseverance of the Perpetual Problem Pertaining to Preaching to Public School Pupils & Why it Persists". University of Massachusetts Law Review. 8 (2): 442–464. Article 3.

- Mencken, H.L.. A Religious Orgy in Tennesse: A Reporter's Account of the Scopes Monkey Trial. Hoboken: Melville House, 2006.

- "Monkey Trial". American Experience |. PBS.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Scopes, John Thomas and William Jennings Bryan. The World's Most Famous Court Trial: Tennesse Evolution Case: A Complete Stenographic Report of the Famous Court Test. Cincinnati: National Book Co., ca. 1925.

- Shapiro, Adam R. Trying Biology: The Scopes Trial, Textbooks, and the Antievolution Movement in American Schools. Chicago: UCP, 2013.

- Shapiro, Adam R. “‘Scopes Wasn't the First’: Nebraska's 1924 Anti-Evolution Trial.” Nebraska History, vol. 94 (Fall 2013), pp. 110–119.

- The Church Case between Prof. Johannes du Plessis and the Dutch Reformed Church in Cape Town, South Africa, on 27 February 1930 – 1931, regarding the Biblical chapter of Genesis and evolution, was a similar event. The Church lost its case. [1]

External

Original materials from and news coverage of the trial:

- Complete trial transcripts and other court documents at darrow.aw.umn.edu/trials

- Mencken's complete columns on the Scopes Trial at the Internet Archive

- Papers of Warner B. Ragsdale, a reporter covering the trial.

- Readings (audio) of H.L. Mencken's reports of the trial from The Baltimore Evening Sun

- Scopes Trial Home Page by Douglas Linder. University of Missouri at Kansas City Law School

- Bryan, William Jennings (1925). "Text of the Closing Statement of William Jennings Bryan at the trial of John Scopes". csudh.edu. Dayton, Tennessee.

- Marks, Jonathan. "Transcript of Bryan's cross-examination". University of North Carolina. Charlotte, NC.

- "Unpublished Photographs from 1925 Tennessee vs. John Scopes "Monkey Trial"". Smithsonian Archives.

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

- 20th century American trials

- Education in Tennessee

- Legal history of Tennessee

- Rhea County, Tennessee

- History of the United States (1918–45)

- Tennessee state case law

- United States creationism and evolution case law

- Evolution and religion

- 1925 in religion

- 1925 in Tennessee

- Scopes Trial

- American Civil Liberties Union litigation

- William Jennings Bryan