Sodium amide

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Sodium amide, sodium azanide[1]

| |

| Other names

Sodamide

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.064 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UN number | 1390 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| NaNH2 | |

| Molar mass | 39.01 g mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colourless crystals |

| Odor | ammonia-like |

| Density | 1.39 g cm−3 |

| Melting point | 210 °C (410 °F; 483 K) |

| Boiling point | 400 °C (752 °F; 673 K) |

| reacts | |

| Solubility | 0.004 g/100 mL (liquid ammonia), reacts in ethanol |

| Acidity (pKa) | 38 (conjugate acid) [2] |

| Structure | |

| orthogonal | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C)

|

66.15 J/mol K |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

76.9 J/mol K |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

-118.8 kJ/mol |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵)

|

-59 kJ/mol |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 4.44 °C (39.99 °F; 277.59 K) |

| 450 °C (842 °F; 723 K) | |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Sodium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide |

Other cations

|

Potassium amide |

Related compounds

|

Ammonia |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Sodium amide, commonly called sodamide, is the inorganic compound with the formula NaNH2. This solid, which is dangerously reactive toward water, is white, but commercial samples are typically gray due to the presence of small quantities of metallic iron from the manufacturing process. Such impurities do not usually affect the utility of the reagent.[citation needed] NaNH2 conducts electricity in the fused state, its conductance being similar to that of NaOH in a similar state. NaNH2 has been widely employed as a strong base in organic synthesis.

Preparation and structure

Sodium amide can be prepared by the reaction of sodium with ammonia gas,[3] but it is usually prepared by the reaction in liquid ammonia using iron(III) nitrate as a catalyst. The reaction is fastest at the boiling point of the ammonia, c. −33 °C. An electride, [Na(NH3)6]+e−, is formed as an reaction intermediate.[4]

- 2 Na + 2 NH3 → 2 NaNH2 + H2

NaNH2 is a salt-like material and as such, crystallizes as an infinite polymer.[5] The geometry about sodium is tetrahedral.[6] In ammonia, NaNH2 forms conductive solutions, consistent with the presence of Na(NH3)6+ and NH2− ions.

Uses

Sodium amide is mainly used as a strong base in organic chemistry, often in liquid ammonia solution. It is the reagent of choice for the drying of ammonia (liquid or gaseous)[citation needed]. One of the main advantages to the use of sodamide is that it is rarely functions as a nucleophile. In the industrial production of indigo, sodium amide is a component of the highly basic mixture that induces cyclisation of N-phenylglycine. The reaction produces ammonia, which is recycled typically.[7]

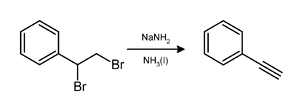

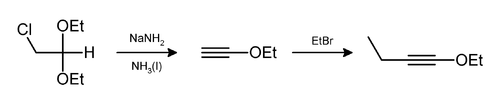

Dehydrohalogenation

Sodium amide induces the loss of two equivalents of hydrogen bromide from a vicinal dibromoalkane to give a carbon-carbon triple bond, as in a preparation of phenylacetylene.[8] Usually two equivalents of sodium amide yields the desired alkyne. Three equivalents are necessary in the preparation of a terminal alkynes because the terminal CH of the resulting alkyne protonates an equivalent amount of base.

Hydrogen chloride and ethanol can also be eliminated in this way,[9] as in the preparation of 1-ethoxy-1-butyne.[10]

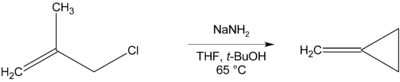

Cyclization reactions

Where there is no β-hydrogen to be eliminated, cyclic compounds may be formed, as in the preparation of methylenecyclopropane below.[11]

Cyclopropenes,[12] aziridines[13] and cyclobutanes[14] may be formed in a similar manner.

Deprotonation of carbon and nitrogen acids

Carbon acids which can be deprotonated by sodium amide in liquid ammonia include terminal alkynes,[15] methyl ketones,[16] cyclohexanone,[17] phenylacetic acid and its derivatives[18] and diphenylmethane.[19] Acetylacetone loses two protons to form a dianion.[20] Sodium amide will also deprotonate indole[21] and piperidine.[22]

Related nonnucleophilic bases

It is however poorly soluble in solvents other than ammonia. Its use has been superseded by the related reagents sodium hydride, sodium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (NaHMDS), and lithium diisopropylamide (LDA).

Other reactions

- Rearrangement with orthodeprotonation[23]

- Oxirane synthesis[24]

- Indole synthesis[25]

- Chichibabin reaction

Safety

Sodium amide reacts violently with water to produce ammonia and sodium hydroxide and will burn in air to give oxides of sodium and nitrogen.

- NaNH2 + H2O → NH3 + NaOH

- 2 NaNH2 + 4 O2 → Na2O + 2 NO2 + 2 H2O

In the presence of limited quantities of air and moisture, such as in a poorly closed container, explosive mixtures of peroxides may form. This is accompanied by a yellowing or browning of the solid. As such, sodium amide is to be stored in a tightly closed container, under an atmosphere of an inert gas. Sodium amide samples which are yellow or brown in color represent explosion risks.[26]

See also

References

- ^ http://goldbook.iupac.org/A00266.html

- ^ Buncel, E.; Menon, B. (1977). "Carbanion mechanisms: VII. Metallation of hydrocarbon acids by potassium amide and potassium methylamide in tetrahydrofuran and the relative hydride acidities". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 141 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)90661-2.

- ^ Bergstrom, F. W. (1955). "Sodium amide". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 3, p. 778.

- ^ Greenlee, K. W.; Henne, A. L.; Fernelius, W. C. (1946). "Sodium Amide". Inorganic Syntheses. 2: 128–135. doi:10.1002/9780470132333.ch38.

- ^ Zalkin, A.; Templeton, D. H. (1956). "The Crystal Structure Of Sodium Amide". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 60 (6): 821–823. doi:10.1021/j150540a042.

- ^ Wells, A. F. (1984). Structural Inorganic Chemistry. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-855370-6.

- ^ L. Lange, W. Treibel "Sodium Amide" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a24_267

- ^ Campbell, K. N.; Campbell, B. K. (1950). "Phenylacetylene". Organic Syntheses. 30: 72

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 4, p. 763. - ^ Jones, E. R. H.; Eglinton, G.; Whiting, M. C.; Shaw, B. L. (1954). "Ethoxyacetylene". Organic Syntheses. 34: 46

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 4, p. 404.

Bou, A.; Pericàs, M. A.; Riera, A.; Serratosa, F. (1987). "Dialkoxyacetylenes: di-tert-butoxyethyne, a valuable synthetic intermediate". Organic Syntheses. 65: 58{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 8, p. 161.

Magriotis, P. A.; Brown, J. T. (1995). "Phenylthioacetylene". Organic Syntheses. 72: 252{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 9, p. 656.

Ashworth, P. J.; Mansfield, G. H.; Whiting, M. C. (1955). "2-Butyn-1-ol". Organic Syntheses. 35: 20{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 4, p. 128. - ^ Newman, M. S.; Stalick, W. M. (1977). "1-Ethoxy-1-butyne". Organic Syntheses. 57: 65

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 6, p. 564. - ^ Salaun, J. R.; Champion, J.; Conia, J. M. (1977). "Cyclobutanone from methylenecyclopropane via oxaspiropentane". Organic Syntheses. 57: 36

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 6, p. 320. - ^ Nakamura, M.; Wang, X. Q.; Isaka, M.; Yamago, S.; Nakamura, E. (2003). "Synthesis and (3+2)-cycloaddition of a 2,2-dialkoxy-1-methylenecyclopropane: 6,6-dimethyl-1-methylene-4,8-dioxaspiro(2.5)octane and cis-5-(5,5-dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-2-ylidene)hexahydro-1(2H)-pentalen-2-one". Organic Syntheses. 80: 144

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ Bottini, A. T.; Olsen, R. E. (1964). "N-Ethylallenimine". Organic Syntheses. 44: 53

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 541. - ^ Skorcz, J. A.; Kaminski, F. E. (1968). "1-Cyanobenzocyclobutene". Organic Syntheses. 48: 55

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 263. - ^ Saunders, J. H. (1949). "1-Ethynylcyclohexanol". Organic Syntheses. 29: 47; Collected Volumes, vol. 3, p. 416.

Peterson, P. E.; Dunham, M. (1977). "(Z)-4-Chloro-4-hexenyl trifluoroacetate". Organic Syntheses. 57: 26{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 6, p. 273.

Kauer, J. C.; Brown, M. (1962). "Tetrolic acid". Organic Syntheses. 42: 97{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 1043. - ^ Coffman, D. D. (1940). "Dimethylethynylcarbinol". Organic Syntheses. 20: 40; Collected Volumes, vol. 3, p. 320.Hauser, C. R.; Adams, J. T.; Levine, R. (1948). "Diisovalerylmethane". Organic Syntheses. 28: 44

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 3, p. 291. - ^ Vanderwerf, C. A.; Lemmerman, L. V. (1948). "2-Allylcyclohexanone". Organic Syntheses. 28: 8

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 3, p. 44. - ^ Hauser, C. R.; Dunnavant, W. R. (1960). "α,β-Diphenylpropionic acid". Organic Syntheses. 40: 38

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 526.

Kaiser, E. M.; Kenyon, W. G.; Hauser, C. R. (1967). "Ethyl 2,4-diphenylbutanoate". Organic Syntheses. 47: 72{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 559.

Wawzonek, S.; Smolin, E. M. (1951). "α,β-Diphenylcinnamonitrile". Organic Syntheses. 31: 52{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 4, p. 387. - ^ Murphy, W. S.; Hamrick, P. J.; Hauser, C. R. (1968). "1,1-Diphenylpentane". Organic Syntheses. 48: 80

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 523. - ^ Hampton, K. G.; Harris, T. M.; Hauser, C. R. (1971). "Phenylation of diphenyliodonium chloride: 1-phenyl-2,4-pentanedione". Organic Syntheses. 51: 128

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 6, p. 928.

Hampton, K. G.; Harris, T. M.; Hauser, C. R. (1967). "2,4-Nonanedione". Organic Syntheses. 47: 92{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 848. - ^ Potts, K. T.; Saxton, J. E. (1960). "1-Methylindole". Organic Syntheses. 40: 68

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 769. - ^ Bunnett, J. F.; Brotherton, T. K.; Williamson, S. M. (1960). "N-β-Naphthylpiperidine". Organic Syntheses. 40: 74

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 816. - ^ Brazen, W. R.; Hauser, C. R. (1954). "2-Methylbenzyldimethylamine". Organic Syntheses. 34: 61

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 4, p. 585. - ^ Allen, C. F. H.; VanAllan, J. (1944). "Phenylmethylglycidic ester". Organic Syntheses. 24: 82

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 3, p. 727. - ^ Allen, C. F. H.; VanAllan, J. (1942). "2-Methylindole". Organic Syntheses. 22: 94

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 3, p. 597. - ^ "Sodium Amide". Princeton, NJ: Princeton University. 2011-03-16. Retrieved 2011-07-20.