Somatostatin

Somatostatin, also known as growth hormone–inhibiting hormone (GHIH) or by several other names, is a peptide hormone that regulates the endocrine system and affects neurotransmission and cell proliferation via interaction with G protein-coupled somatostatin receptors and inhibition of the release of numerous secondary hormones. Somatostatin inhibits insulin and glucagon secretion.[5]

Somatostatin has two active forms produced by alternative cleavage of a single preproprotein: one of 14 amino acids (shown in infobox to right), the other of 28 amino acids[6] which is the short form with another 14 amino acids at one end.[7]

Among the vertebrates, there exist six different somatostatin genes that have been named SS1, SS2, SS3, SS4, SS5, and SS6.[8] Zebrafish have all 6.[8] The six different genes along with the five different somatostatin receptors allows somatostatin to possess a large range of functions.[9] Humans have only one somatostatin gene, SST.[10][11][12]

Nomenclature

Synonyms of somatostatin are as follows:

- growth hormone–inhibiting hormone (GHIH)

- growth hormone release–inhibiting hormone (GHRIH)

- somatotropin release–inhibiting factor (SRIF)

- somatotropin release–inhibiting hormone (SRIH)

Production

Digestive system

Somatostatin is secreted at several locations in the digestive system:

- Delta cells in the pyloric antrum, the duodenum and the pancreatic islets[13]

Somatostatin released in the pyloric antrum travels via the portal venous system to the heart, then enters the systemic circulation to reach the locations where it will exert its inhibitory effects. In addition, somatostatin release from delta cells can act in a paracrine manner.[13]

In the stomach, somatostatin acts directly on the acid-producing parietal cells via a G-protein coupled receptor (which inhibits adenylate cyclase, thus effectively antagonising the stimulatory effect of histamine) to reduce acid secretion.[13] Somatostatin can also indirectly decrease stomach acid production by preventing the release of other hormones, including gastrin, secretin and histamine which effectively slows down the digestive process.

Brain

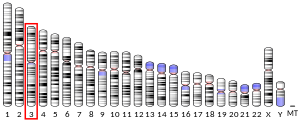

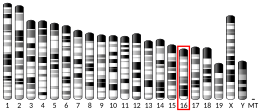

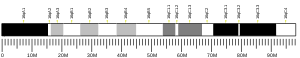

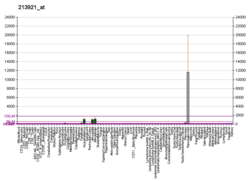

|

|

Somatostatin is produced by neuroendocrine neurons of the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus. These neurons project to the median eminence, where somatostatin is released from neurosecretory nerve endings into the hypothalamo-hypophysial system through neuron axons. Somatostatin is then carried to the anterior pituitary gland, where it inhibits the secretion of growth hormone from somatotrope cells. The somatostatin neurons in the periventricular nucleus mediate negative feedback effects of growth hormone on its own release; the somatostatin neurons respond to high circulating concentrations of growth hormone and somatomedins by increasing the release of somatostatin, so reducing the rate of secretion of growth hormone.

Somatostatin is also produced by several other populations that project centrally, i.e., to other areas of the brain, and somatostatin receptors are expressed at many different sites in the brain. In particular, there are populations of somatostatin neurons in the arcuate nucleus,[citation needed] the hippocampus,[citation needed] and the brainstem nucleus of the solitary tract.[citation needed]

Actions

Somatostatin is classified as an inhibitory hormone,[6] and is induced by low pH.[citation needed]. Its actions are spread to different parts of the body.

Anterior pituitary

In the anterior pituitary gland, the effects of somatostatin are:

- Inhibit the release of growth hormone (GH)[14] (thus opposing the effects of growth hormone–releasing hormone (GHRH))

- Inhibit the release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)[15]

- Inhibit adenylyl cyclase in parietal cells.

- Inhibits the release of prolactin (PRL)

Gastrointestinal system

- Somatostatin is homologous with cortistatin (see somatostatin family) and suppresses the release of gastrointestinal hormones

- Decrease rate of gastric emptying, and reduces smooth muscle contractions and blood flow within the intestine[14]

- Suppresses the release of pancreatic hormones

- Suppresses the exocrine secretory action of pancreas.

Synthetic substitutes

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2009) |

Octreotide (brand name Sandostatin, Novartis Pharmaceuticals) is an octapeptide that mimics natural somatostatin pharmacologically, though is a more potent inhibitor of growth hormone, glucagon, and insulin than the natural hormone and has a much longer half-life (approximately 90 minutes, compared to 2–3 minutes for somatostatin). Since it is absorbed poorly from the gut, it is administered parenterally (subcutaneously, intramuscularly, or intravenously). It is indicated for symptomatic treatment of carcinoid syndrome and acromegaly. It is also finding increased use in polycystic diseases of the liver and kidney.

Lanreotide (brand name Somatuline, Ipsen Pharmaceuticals)is a medication used in the management of acromegaly and symptoms caused by neuroendocrine tumors, most notably carcinoid syndrome. It is a long-acting analog of somatostatin, like octreotide. It is available in several countries, including the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada, and was approved for sale in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on August 30, 2007.

Evolutionary history

There are six somatostatin genes that have been discovered in vertebrates. The current proposed history as to how these six genes arose is based on the three whole-genome duplication events that took place in vertebrate evolution along with local duplications in teleost fish. An ancestral somatostatin gene was duplicated during the first whole-genome duplication event (1R) to create SS1 and SS2. These two genes were duplicated during the second whole-genome duplication event (2R) to create four new somatostatin genes: SS1, SS2, SS3, and one gene that was lost during the evolution of vertebrates. Tetrapods retained SS1 (also known as SS-14 and SS-28) and SS2 (also known as cortistatin) after the split in the sarcopterygii and actinopterygii lineage split. In teleost fish, SS1, SS2, and SS3 were duplicated during the third whole-genome duplication event (3R) to create SS1, SS2, SS4, SS5, and two genes that were lost during the evolution of teleost fish. SS1 and SS2 went through local duplications to give rise to SS6 and SS3.[8]

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000157005 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000004366 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "somatostatin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2016. Web. 04 mag. 2016 <http://www.britannica.com/science/somatostatin>.

- ^ a b Costoff A. "Sect. 5, Ch. 4: Structure, Synthesis, and Secretion of Somatostatin". Endocrinology: The Endocrine Pancreas. Medical College of Georgia. p. 16. Archived from the original on April 5, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ somatostatin preproprotein [Homo sapiens] See Features

- ^ a b c Liu Y, Lu D, Zhang Y, Li S, Liu X, Lin H (2010). "The evolution of somatostatin in vertebrates". Gene. 463 (1–2): 21–28. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2010.04.016. PMID 20472043.

- ^ Gahete MD, Cordoba-Chacón J, Duran-Prado M, Malagón MM, Martinez-Fuentes AJ, Gracia-Navarro F, Luque RM, Castaño JP (2010). "Somatostatin and its receptors from fish to mammals". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1200: 43–52. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05511.x. PMID 20633132.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: Somatostatin".

- ^ Shen LP, Pictet RL, Rutter WJ (August 1982). "Human somatostatin I: sequence of the cDNA". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79 (15): 4575–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.79.15.4575. PMC 346717. PMID 6126875.

- ^ Shen LP, Rutter WJ (April 1984). "Sequence of the human somatostatin I gene". Science. 224 (4645): 168–71. doi:10.1126/science.6142531. PMID 6142531.

- ^ a b c Boron, Walter F.; Boulpaep, Emile L. (2012). Medical Physiology, 2e Updated Edition, 2nd Edition (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 9781437717532.

- ^ a b Bowen R (2002-12-14). "Somatostatin". Biomedical Hypertextbooks. Colorado State University. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ^ First Aid for the USMLE Step 1, 2010. Page 286.

- ^ a b Costoff A. "Sect. 5, Ch. 4: Structure, Synthesis, and Secretion of Somatostatin". Endocrinology: The Endocrine Pancreas. Medical College of Georgia. p. 17. Archived from the original on March 31, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Van der Meulen T, Donaldson CJ, Cáceres E, Hunter AE, Cowing-Zitron C, Pound LD, Adams MW, Zembrzycki A, Grove KL, Huising MO (2016-06-15). "Urocortin3 mediates somatostatin-dependent negative feedback control of insulin secretion". Nature Medicine. doi:10.1038/nm.3872. PMID 26076035. Retrieved 2016-05-30.