Sophia (wisdom)

Sophia (σοφία, Greek for "wisdom") is a central idea in Hellenistic philosophy and religion, Platonism, Gnosticism, Orthodox Christianity, Esoteric Christianity, as well as Christian mysticism. Sophiology is a philosophical concept regarding wisdom, as well as a theological concept regarding the wisdom of the biblical God.

Sophia is honored as a goddess of wisdom by Gnostics, as well as by some Neopagan, New Age, and Goddess spirituality groups. In Orthodox and Roman Catholic Christianity, Sophia, or rather Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom), is an expression of understanding for the second person of the Holy Trinity, (as in the dedication of the church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople) as well as in the Old Testament, as seen in the Book of Proverbs 9:1, but not an angel or goddess.

Platonism

Plato, following his teacher, Socrates (and, it is likely, the older tradition of Pythagoras), understands philosophy as φιλοσοφία (philo-sophia, or, literally, a friend of Wisdom). This understanding of philosophia permeates Plato's dialogues, especially the Republic. In that work, the leaders of the proposed utopia are to be philosopher kings: rulers who are friends of sophia or Wisdom.

Sophia is one of the four cardinal virtues in Plato's Protagoras.

The Pythian Oracle (Oracle of Delphi) reportedly answered the question of "who is the wisest man of Greece?" with "Socrates!" Socrates defends this verdict in his Apology to the effect that he, at least, knows that he knows nothing. As is evident in Plato's portrayals of Socrates, this does not mean Socrates' wisdom was the same as knowing nothing; but rather that his skepticism towards his own self-made constructions of knowledge left him free to receive true Wisdom as a spontaneous insight or inspiration. This contrasted with the attitude of contemporaneous Greek Sophists, who claimed to be wise and offered to teach wisdom for pay.

Old Testament and Jewish texts

Septuagint

The Greek noun sophia is the translation of "wisdom" in the Greek Septuagint for Hebrew חכמות Ḥokmot. Wisdom is a central topic in the "sapiential" books, i.e. Proverbs, Psalms, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, Book of Wisdom, Wisdom of Sirach, and to some extent Baruch (the last three are Apocryphal / Deuterocanonical books of the Old Testament.)

Philo and the Logos

Philo, a Hellenised Jew writing in Alexandria, attempted to harmonise Platonic philosophy and Jewish scripture. Also influenced by Stoic philosophical concepts, he used the Greek term logos, "word," for the role and function of Wisdom, a concept later adapted by the author of the Gospel of John in the opening verses and applied to Jesus Christ as the eternal Word (Logos) of God the Father.[1]

Christianity

In Christian theology, "wisdom" (Hebrew: Chokhmah, Greek: Sophia, Latin: Sapientia) describes an aspect of God, or the theological concept regarding the wisdom of God.[citation needed]

New Testament

Jesus directly mentions Wisdom in the Gospel of Matthew:

The Son of man came eating and drinking, and they say, Behold a man gluttonous, and a winebibber, a friend of publicans and sinners. But wisdom is justified of her children.

St. Paul refers to the concept, notably in 1 Corinthians, but obscurely, deconstructing worldly wisdom:

Where is the wise? where is the scribe? where is the disputer of this world? hath not God made foolish the wisdom of this world?

Paul sets worldly wisdom against a higher wisdom of God:

But we speak the wisdom of God in a mystery, even the hidden wisdom, which God ordained before the world unto our glory.

The Epistle of James (James 3:13–18; cf. James 1:5) distinguishes between two kinds of wisdom. One is a false wisdom, which is characterized as "earthly, sensual, devilish" and is associated with strife and contention. The other is the 'wisdom that comes from above':

But the wisdom that is from above is first pure, then peaceable, gentle, [and] easy to be intreated, full of mercy and good fruits, without partiality, and without hypocrisy.

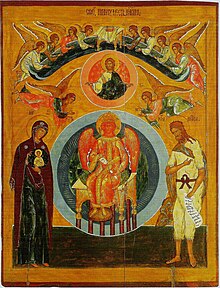

Eastern Orthodoxy

In the mystical theology of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Holy Wisdom is understood as the Divine Logos who became incarnate as Jesus Christ;[2] this belief being sometimes also expressed in some Eastern Orthodox icons.[3][4][5][6][7] In Eastern Orthodoxy humility is the highest wisdom and is to be sought more than any other virtue. Not only does humility cultivate the Holy Wisdom, but it (in contrast to knowledge) is the defining quality that grants people salvation and entrance into Heaven.[8] The Hagia Sophia or Holy Wisdom church in Constantinople was the religious center of the Eastern Orthodox Church for nearly a thousand years.

In the Divine Liturgy of the Orthodox Church, the exclamation Sophia! or in English Wisdom! will be proclaimed by the deacon or priest at certain moments, especially before the reading of scripture, to draw the congregation's attention to sacred teaching.

The concept of Sophia has been championed as a key part of the Godhead by some Eastern Orthodox religious thinkers. These included Vladimir Solovyov, Pavel Florensky, Nikolai Berdyaev, and Sergei Bulgakov whose book Sophia: The Wisdom of God is in many ways the apotheosis of Sophiology. For Bulgakov, the Sophia is co-existent with the Trinity, operating as the feminine aspect of God in concert with the three masculine principles of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Vladimir Lossky rejects Solovyev and Bulgakov's teachings as error. Lossky states that Wisdom as an energy of God (just as love, faith and grace are also energies of God) is not to be ascribed to be the true essence of God, as to do so is to deny the apophatic and incomprehensible nature of the Divine essence.[9] Bulgakov's work was denounced by the Russian Orthodox as heretical.[2][10]

Roman Catholic mysticism

In Roman Catholic mysticism, the Doctor of the Church St. Hildegard of Bingen celebrated Sophia as a cosmic figure in both her writing and her art.[11] Sophia, in Catholic theology, is the Wisdom of God, and is thus eternal.

Protestant mysticism

Within the Protestant tradition in England, Jane Leade, 17th-century Christian mystic, Universalist, and founder of the Philadelphian Society, wrote copious descriptions of her visions and dialogues with the "Virgin Sophia" who, she said, revealed to her the spiritual workings of the Universe.[12]

Leade was hugely influenced by the theosophical writings of 16th century German Christian mystic Jakob Böhme, who also speaks of the Sophia in works such as The Way to Christ.[13] Jakob Böhme was very influential to a number of Christian mystics and religious leaders, including George Rapp and the Harmony Society.[14]

Sophia can be described as the wisdom of God, and, at times, as a pure virgin spirit which emanates from God. The Sophia is seen as being expressed in all creation and the natural world as well as, for some of the Christian mystics mentioned above, integral to the spiritual well-being of humankind, the church, and the cosmos. The Virgin is seen as outside creation but compassionately interceding on behalf of humanity to alleviate its suffering by illuminating true spiritual seekers with wisdom and the love of God.

The main difference between the concept of Sophia found in most traditional forms of Christian mysticism and the one more aligned with the Gnostic view of Sophia is that to many Christian mystics she is not seen as fallen or in need of redemption. Conversely, she is not as central in most forms of established Christianity as she is in Gnosticism, but to some Christian mystics the Sophia is a very important concept.

In the Heavenly Faith school of thought, the Holy Spirit is synonymous with Sophia, being the feminine counterpart to the masculine Logos. Whereas the latter is incarnated in Jesus of Nazareth, the former is effectively incarnate in the Church in so far as She is the spirit which circulates through and binds together all Christians.[15]

In Christology

The Old Testament theme of wisdom also proved its worth for the first Christians when reflecting on their experience of Jesus.[16] The conceptuality offered various possibilities.[17]

Proverbs vividly personifies the divine attribute or function of wisdom, which existed before the world was made, revealed God, and acted as God's agent in creation (Prov 8:22–31 cf. 3:19; Wis 8:4–6Template:Bibleverse with invalid book; Sir 1:4,9). Wisdom dwelt with God (Prov 8:22–31; cf. Sir 24:4; Wis 9:9–10Template:Bibleverse with invalid book) and being the exclusive property of God was as such inaccessible to human beings (Job 28:12–13,20–1,23–27). It was God who "found" wisdom (Bar 3:29–37) and gave her to Israel: "He found the whole way to knowledge, and gave her to Jacob his servant and to Israel whom he loved. Afterward she appeared upon earth and lived among human beings" (Bar 3:36–37; Sir 24:1–12). As a female figure (Sir. 1:15; Wis. 7:12), wisdom addressed human beings (Prov. 1:20-33; 8:1-9:6) inviting to her feast those who are not yet wise (Prov. 9:1-6). The finest passage celebrating the divine wisdom (Wis. 7:22b-8:1) includes the following description: "She is a breath of the power of God, and the radiance of the glory of the Almighty... She is a reflection of eternal light, a spotless mirror of the working of God, and an image of his goodness" (Wis 7:25–26Template:Bibleverse with invalid book). No wonder then that Solomon, the archetypal wise person, fell in love with wisdom: "I loved her and sought her from my youth; I desired to take her for my bride, and became enamored of her beauty" (Wis 8:2Template:Bibleverse with invalid book). Such was the radiant beauty of the wisdom exercised by God both in creation and in relations with the chosen people.[18]

In understanding and interpreting Christ, the New Testament uses various strands from these accounts of wisdom. First, like wisdom, Christ pre-existed all things and dwelt with God John 1:1–2); second, the lyric language about wisdom being the breath of the divine power, reflecting divine glory, mirroring light, and being an image of God, appears to be echoed by 1 Corinthians 1:17-18, 24-5 (verses which associate divine wisdom with power), by Hebrew 1:3Template:Bibleverse with invalid book ("he is the radiance of God's glory"), John 1:9 ("the true light that gives light to everyone"), and Colossians 1:15 ("the image of the invisible God"). Third, the New Testament applies to Christ the language about wisdom's cosmic significance as God's agent in the creation of the world: "all things were made through him, and without him nothing was made that was made" (John 1:3; see Col 1:16 Heb 1:2). Fourth, faced with Christ's crucifixion, Paul vividly transforms the notion of divine wisdom's inaccessibility (1 Cor. 1:17-2:13). "The wisdom of God" (1 Cor. 1:21) is not only "secret and hidden" (1 Cor. 2:7) but also, defined by the cross and its proclamation, downright folly to the wise of this world (1 Cor. 1:18-25; see also Matt 11:25–7). Fifth, through his parables and other ways, Christ teaches wisdom (Matt 25:1–12 Luke 16:1–18, cf. also Matt 11:25–30). He is 'greater' than Solomon, the Old Testament wise person and teacher par excellence (Matt 12:42). Sixth, the New Testament does not, however, seem to have applied to Christ the themes of Lady Wisdom and her radiant beauty. Pope Leo the Great (d. 461), however, recalled Proverbs 9:1 by picturing the unborn Jesus in Mary's womb as "Wisdom building a house for herself" (Epistolae, 31. 2-3).[16] Strands from the Old testament ideas about wisdom are more or less clearly taken up (and changed) in New Testament interpretations of Christ. Here and there the New Testament eventually not only ascribes wisdom roles to Christ, but also makes the equation "divine wisdom=Christ" quite explicit. Luke reports how the boy Jesus grew up "filled with wisdom" (Luke 2:40; see Luke 2:52). Later, Christ's fellow-countrymen were astonished "at the wisdom given to him" (Mark 6:2). Matthew 11:19 thinks of him as divine wisdom being "proved right by his deeds" (see, however, the different and probably original version of Luke 7:35).[19] Possibly Luke 11:49 wishes to present Christ as "the wisdom of God". Paul names Christ as "the wisdom of God" (1 Cor. 1:24) whom God "made our wisdom" (1 Cor. 1:30; cf. 1:21). A later letter softens the claim a little: in Christ "all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge lie hidden" (Col 2:3). Beyond question, the clearest form of the equation "the divine wisdom=Christ" comes in 1 Corinthians 1:17-2:13. Yet, even there Paul's impulse is to explain "God's hidden wisdom" not so much as the person of Christ himself, but rather as God's "wise and hidden purpose from the very beginning to bring us to our destined glory" (1 Cor. 2:7). In other words, when Paul calls Christ "the wisdom of God", even more than in the case of other titles, God's eternal plan of salvation overshadows everything.[16]

In Patristics

At times the Church Fathers named Christ as "Wisdom". Therefore, when rebutting claims about Christ's ignorance, Gregory of Nazianzus insisted that, inasmuch as he was divine, Christ knew everything: "How can he be ignorant of anything that is, when he is Wisdom, the maker of the worlds, who brings all things to fulfilment and recreates all things, who is the end of all that has come into being?" (Orationes, 30.15). Irenaeus represents another, minor patristic tradition which identified the Spirit of God, and not Christ himself, as "Wisdom" (Adversus haereses, 4.20.1-3; cf. 3.24.2; 4.7.3; 4.20.3). He could appeal to Paul's teaching about wisdom being one of the gifts of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor. 12:8). However, the majority applied to Christ the title/name of "Wisdom". Eventually the Emperor Constantine set a pattern for Eastern Christians by dedicating a church to Christ as the personification of divine wisdom.[16] In Constantinople, under Emperor Justinian, Santa Sophia ("Holy Wisdom") was rebuilt, consecrated in 538, and became a model for many other Byzantine churches. Nevertheless, in the New testament and subsequent Christian thought (at least Western thought) "the Word" or Logos came through more clearly than "the Wisdom" of God as a central, high title of Christ. The portrayal of the Word in the prologue of John's Gospel shows a marked resemblance to what is said about wisdom in Proverbs 8:22–31 and Sirach 24:1–2. Yet, that Prologue speaks of the Word, not the Wisdom, becoming flesh and does not follow Baruch in saying that "Wisdom appeared upon earth and lived among human beings" (Bar 3:37. When focusing in a classic passage on what "God has revealed to us through the Spirit" (1 Cor. 2:10), Paul had written of the hidden and revealed wisdom of God (1 Cor. 1:17-2:13). Despite the availability of this wisdom language and conceptuality, John prefers to speak of "the Word" (John 1:1,14; cf. 1 John 1:1; Rev 19:13), a term that offers a rich array of meanings.[16]

Gnosticism

Contemporary pagan Goddess worship

Sophia is widely worshiped as a goddess of wisdom by gnostics and pagans today, including wiccan spirituality.[20][21] Books relating to the contemporary pagan worship of the goddess Sophia include: Sophia, Goddess of Wisdom, by Caitlin Matthews, The Cosmic Shekinah by Sorita d'Este and David Rankine (which includes Sophia as one of the major aspects of the goddess of wisdom), and Inner Gold: Understanding Psychological Projection by Robert A. Johnson.

New Age spirituality

The goddess Sophia was introduced into Anthroposophy by its founder, Rudolf Steiner, in his book The Goddess: From Natura to Divine Sophia[22] and a later compilation of his writings titled Isis Mary Sophia. Sophia also figures prominently in Theosophy, a spiritual movement which Anthroposophy was closely related to. Helena Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy, described it in her essay What is Theosophy? as an esoteric wisdom doctrine, and said that the "Wisdom" referred to was "an emanation of the Divine principle" typified by "...some goddesses -- Metis, Neitha, Athena, the Gnostic Sophia..."[23]

A New Age[24] Ascended Master Teachings[25] esoteric interfaith spiritual community currently has its center at what it calls Sancta Sophia Seminary located in Tahlequah, Oklahoma.[26]

Art

The artwork The Dinner Party features a place setting for Sophia.[27]

See also

- Christology

- Re-Imagining: Christian feminist conference

- Sophia (name)

- Sophiology

- Sophism

- Sufism

- Valentinus

- Wisdom literature

References

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "John" p. 302-310

- ^ a b Pomazansky, Protopresbyter Michael (1963, in Russian), Orthodox Dogmatic Theology: A Concise Exposition, Platina CA: St Herman of Alaska Brotherhood (published 1994, Eng. Tr. Hieromonk Seraphim Rose), pp. 357 ff, ISBN 0-938635-69-7

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=and|publication-date=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) Text available online Intratext.com - ^ "OCA - Feasts and Saints". Ocafs.oca.org. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ Artist Olga B. Kuznetsova - various icon. "Private collection - Saint Sophia the Wisdom of God, 27х31 sm, 2009 year". Iconpaint.ru. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ "Orthodox icons, Byzantine icons, Greek icons - Religious icons: Holy Sophia the Wisdom of God". Istok.net. 2012-07-20. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Holy Wisdom - F78". Skete.com. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ St. Nikitas Stithatos (1999), "On the Practice of the Virtues - On the Inner Nature of Things", The Philokalia: The Complete Text, vol. Four, London: Faber and Faber, ISBN 0-571-19382-X

- ^ This was the basis of the theological development of Fr. Bulgakov, and also his fundamental error: for he sought to see in the energy of Wisdom (Sophia), which he identified with the essence, the very principle of the Godhead. In fact, God is not determined by any of his attributes: all determinations are inferior to Him, logically posterior to His being in itself, in its essence. pgs 80-81 The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church, by Vladimir Lossky SVS Press, 1997. (ISBN 0-913836-31-1) James Clarke & Co Ltd, 1991. (ISBN 0-227-67919-9)

- ^ "Orthodoxwiki states this also as heresy". Orthodoxwiki.org. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ Painting by Hildegard of Bingen depicting Sophia.GCSU.edu Also, there's a CD of music written by Hildegard of Bingen entitled "Chants in Praise of Sophia". Classicsonline.com

- ^ Hirst, Julie (2005). Jane Leade: Biography of a Seventeenth-Century Mystic.

- ^ Jakob Böhme, The Way to Christ (1622) Passtheword.org

- ^ Arthur Versluis, "Western Esotericism and The Harmony Society", Esoterica I (1999) pp. 20-47 MSU.edu

- ^ [2]

- ^ a b c d e For this specific section and themes, compare Gerald O'Collins, Christology: A Biblical, Historical, and Systematic Study of Jesus. Oxford:Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 35-41.

- ^ Cf. R. E Murphy, The Tree of Life: An Exploration of Biblical Wisdom Literature. New York: Doubleday (2002); A. O'Boyle, Towards a Contemporary Wisdom Christology. Rome: Gregorian University Press (1993); G. O'Collins, Salvation for All: God's Other Peoples. Oxford: OUP (2008), pp. 54-63, 230-247.

- ^ For a summary account of wisdom in pre-Christian Judaism, cf. R.E. Murphy, "Wisdom in the Old Testament", Anchor Bible Dictionary (1992), vi. 920-931.

- ^ On Matthew's identification of Jesus with wisdom, cf. J. D. G. Dunn, Christology in the Making. London: SCM Press (1989), pp. 197-206.

- ^ "Sophia : Goddess of Wisdom". Sistersofearthsong.com. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ "Goddess Sophia". Sophiastemple.com. 2012-06-20. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ Steiner, Rudolf (2001). The Goddess: From Natura to the Divine Sophia : Selections from the Work of Rudolf Steiner. Sophia Books, Rudolf Steiner Press. p. 96. ISBN 1855840944.

- ^ "What is Theosophy?". Age-of-the-sage.org. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ [4][dead link]

- ^ "Sancta Sophia Seminary website". Sanctasophia.org. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ Place Settings. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved on 2015-08-06.

Bibliography

- Caitlin Matthews, Sophia: Goddess of Wisdom (London: Mandala, 1991) ISBN 0-04-440590-1.

- Brenda Meehan, "Wisdom/Sophia, Russian identity, and Western feminist theology", Cross Currents, 46(2), 1996, pp. 149–168.

- Thomas Schipflinger, Sophia-Maria (in German: 1988; English translation: York Beach, ME: Samuel Wiser, 1998) ISBN 1-57863-022-3.

- Arthur Versluis, Theosophia: hidden dimensions of Christianity (Hudson, NY: Lindisfarne Press, 1994) ISBN 0-940262-64-9.

- Arthur Versluis, Wisdom’s children: a Christian esoteric tradition (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1999) ISBN 0-7914-4330-2.

- Arthur Versluis (ed.) Wisdom’s book: the Sophia anthology (St.Paul, Min: Paragon House, 2000) ISBN 1-55778-783-2.

- Priscilla Hunt, "The Wisdom Iconography of Light: The Genesis, Meaning and Iconographic Realization of a Symbol" due to appear in “'Spor o Sofii' v Khristianskoi Kul’ture", V.L. Ianin, A.E. Musin, ed., Novgorodskii Gos. Universitet, forthcoming in 2008.

- Priscilla Hunt, "Confronting the End: The Interpretation of the Last Judgment in a Novgorod Wisdom Icon", ru, 65, 2007, 275-325.

- Priscilla Hunt, "The Novgorod Sophia Icon and 'The Problem of Old Russian Culture' Between Orthodoxy and Sophiology", Symposion: A Journal of Russian Thought, vol. 4-5, (2000), 1-41.

- Priscilla Hunt, "Andrei Rublev’s Old Testament Trinity Icon in Cultural Context", The Trinity-Sergius Lavr in Russian History and Culture: Readings in Russian Religious Culture, vol. 3, Deacon Vladimir Tsurikov, ed., Jordanville, NY: Holy Trinity Seminary Press, 2006, 99-122.