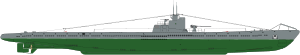

Soviet S-class submarine

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | S class |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Template:Sclass- |

| Succeeded by | K class |

| Completed | 56 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Attack submarine |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 77.8 m (255 ft 3 in) |

| Beam | 6.4 m (21 ft 0 in) |

| Draught | 4.4 m (14 ft 5 in) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed |

|

| Range |

|

| Test depth | 100 m (330 ft) |

| Complement |

|

| Sensors and processing systems |

|

| Armament |

|

The S-class or Srednyaya (Russian: Средняя, "medium") submarines were part of the Soviet Navy's underwater fleet during World War II. Unofficially nicknamed Stalinets (Russian: Сталинец, "follower of Stalin"; not to be confused with the submarine L-class L-2 Stalinets of 1931), boats of this class were the most successful and achieved the most significant victories among all Soviet submarines. In all, they sank 82,770 gross register tons (GRT) of merchant shipping and seven warships, which accounts for about one-third of all tonnage sunk by Soviet submarines during the war.

Project history

The history of the S class represents a turn in warship development. It was a result of international collaboration between Soviet and German engineers that resulted in two different (but nevertheless related) classes of submarines often pitted against each other in the war.

In the early 1930s the Soviet government started a massive program of general rearmament, including naval expansion. Submarines were one key point of this program, but currently available types did not completely satisfy naval authorities. The recently developed Template:Sclass- was satisfactory, but it was designed specifically for shallow Baltic Sea service and lacked true ocean-going capabilities. The larger boats of the Soviet Navy were quickly becoming obsolete.

As a result, the government commissioned several engineers to search for a suitable design for a medium-sized ocean-going submarine, and this search soon brought success. After its defeat in World War I, the German Weimar Republic was forbidden under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles to have submarines or build them in its own yards. Germany circumvented this restriction by creating various subsidiaries of their shipbuilding and design companies in third countries. One of these proxies, the Netherlands-based NV Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw (IvS), a subsidiary of Deutsche Schiff- und Maschinenbau AG-AG Weser, was developing a submarine that matched Soviet requirements. The Spanish government, during General Primo de Rivera's dictatorship, showed interest in obtaining such a submarine for the Spanish Navy. Several German naval officers (including Wilhelm Canaris) visited Spain and struck a deal with a Spanish businessman, Horacio Echevarrieta. A single submarine was built in 1929–1930, and was tested at sea early in 1931, under the manufacturer's designation of submarino E-1, since no navy had yet commissioned the ship.

The government of the Second Spanish Republic showed a clear preference for British submarine designs. Designers and builders then went to offer the design and the boat for sale to return their cost. Soviet engineers, among others, visited the yard in 1932 and were generally satisfied with the design, but suggested several modifications and improvements, in expectation of future local production. Another group of engineers went next year to the IvS office in The Hague, as well as the Bremen office of Deschimag, and then attended the completed boat's trials in Cartagena. Echevarrieta's imprisonment for his connection with the October 1934 Revolution made the Spanish Navy lose any interest in the submarine, which was finally sold to the Turkish Navy in 1935, in which it served until 1947 under the name of Gür.

Despite several problems encountered during the boat's trials, the design was considered satisfactory and the Soviet government bought it, with the condition Deschimag make the suggested improvements and assist with the building of several prototypes, which it did. The modifications resulted in a significant reworking of the project, redesignated E-2. Blueprints were received from Germany at the end of 1933 and on August 14, 1934, the design was officially approved for production, designated IX series. Construction of the first two prototypes commenced in December 1934 at the Baltic Shipyard (Baltiysky zavod) in Leningrad, using partially German equipment. In April 1935, the third prototype was laid down as well.

By the time the third prototype was started, it became obvious building the boats with foreign equipment would be too expensive, so the design was reworked slightly to use only domestically produced equipment. The result of this modification was the IX-bis series and went to mass production in 1936. Initially the first prototypes received the official designations N-1, N-2, and N-3 (Nemetskaya, "German") but in October 1937 they were re-designated S-x (Srednyaya, "Medium"). In the West, the class was much more widely known for its nickname, Stalinets, coined with reference to earlier boats of the Leninets type, but it was never featured in any official documents.

The E-1 boat was eventually sold to Turkey in 1935, and was a prototype for German's own boats of Type I. This design was later improved to become the famous Type VII[citation needed] and Type IX U-boats of the Kriegsmarine[citation needed].

Building and trials

Five navy yards were employed in series production of the class, three in Leningrad (#189, #194 and #196), one in Nikolayev (#198) and one in Gorky (#112). Boats for Pacific Fleet were assembled from prefabricated sections, delivered by railroad, in Vladivostok's plant #202. The first boat was completed in the beginning of December 1935, and made her first dive on December 15. Next August both first boats entered official trials, and while several requirements were not met (for example, speed was 0.5 kt (0.9 km/h, 0.6 mph) lower than the specified 20 kt {37 km/h, 22 mph}) and there were some technical difficulties, the project was considered successful and the boats were commissioned into the Soviet Navy.

The third boat, while still using other German machinery, was powered by Soviet-made diesels, due to delays in delivery of originally intended ones. However, adaptation to significantly different domestic engines required significant redesigns that slowed construction. These modifications were later included into the official blueprints and were the foundation of the later, completely domestically build production series. These series were produced for all four fleets, with boats for Baltic, Northern, and Pacific Fleets being built in Leningrad, Black Sea Fleet boats in Nikolayev, and some boats for Baltic and North in Gorky.

During the war, the former riverboat production yard #638 in Astrakhan was employed for completion of several boats constructed in Leningrad and Gorky. Several boats were not completed: S-36, S-37 and S-38 were scuttled in the Nikolayev yard before the city was captured by Germans, and S-27 to S-30, S-45 and S-47, frozen during the war, were not completed after it, as their design was considered already obsolete. These boats were generally scrapped; S-27's hull was eventually utilized for a workshop ship.

Technical description

There existed three series-produced variations, differing mostly in their equipment. The first series utilized German engines and batteries, while the second was produced with domestic machinery. The third series introduced further improvements aimed mostly at lowering production cost and time, and the fourth series, albeit planned, was cancelled due to the beginning of the war.

IX series

Only three ships were built in this group, S-1, S-2 and S-3, using partially German-supplied machinery. The boats were of semi-double hull type, with riveted pressure hull and welded light hull sections in the superstructure and extremities for improved seaworthiness. The sail was medium-sized and oval in plane, to reduce water drag. It housed the conning tower, the bridge, periscope fairings and a 45 mm (1.77 in) anti-aircraft gun. A net cutter was fitted atop the bow. The hull was separated into seven compartments, three of which were able to withstand 10 atm pressure. Nine main ballast tanks, separated into three groups (4 bow, 2 stern, 3 midships), together with a balancing tank and a quick dive tank were placed in the light hull. Trimming tanks were inside the pressure hull. Ballast tanks were emptied by pressurized air or engines exhaust, thus removing the need for ballast pumps.

The boats were powered by two MAN М6V49/48 four-stroke atmospheric reversive diesels (2000 hp each at 465 rev/min) that drove two fixed pitch propellers together with two Electrosila PG-72/35 electric motors (550 hp at 275 rev/min), connecting by BAMAG (Berlin-Anhaltische Maschinenbau AG) type friction clutches. Delivery of the engines for the third boat was constantly delayed and eventually it was equipped with domestically produced ones. For underwater propulsion energy was supplied by 124 APA 38-MAK-760 accumulators, equipped with K-5 hydrogen burners. The batteries lacked the traditional central walkway, instead using special service trolleys suspended from the deckhead. This design significantly decreased the height of the battery compartment, freeing space for the crew. The electrical system omitted the complicated layout common on earlier Soviet designs, and was simple and reliable. All connections were insulated and the bulkhead feedthroughs were designed to withstand the same pressure as the bulkheads themselves. It had better maneuverability than other smaller Soviet, German, British and Italian submarines (e.g. the British U-class submarines, the German Type VII submarines and the Italian Template:Sclass-).[citation needed]

The vessels were equipped with six torpedo tubes (four bow and two stern) of 533 mm (21 in) caliber. Six spare torpedoes could be stored in the racks of the bow torpedo compartment, so the complete load was 12 torpedoes. Usually 53-38 torpedoes were used, as the high-speed 53-39 torpedoes were available only in limited numbers, and the electric ET-80 torpedoes were unreliable and the crews did not like them. It was also possible to launch mines through the torpedo tubes. No torpedo automation was installed, and all shooting was manual. The stern tubes had an interesting feature: instead of the usual doors, they were closed by a special rotating cylinder that streamlined the contour of the stern when the tubes were not in use. A 45 mm (1.77 in) semi-automatic anti-aircraft gun was mounted on the conning tower, and a 100 mm (3.9 in) gun on the deck for surface combat.

Observation and communication equipment was somewhat less than top-level, but generally adequate. The boats were equipped with two periscopes, observation PZ-7.5 and targeting PA-7.5, mounted very close to each other and reports existed of difficulties in using them simultaneously. Several radios were installed. The Mars-12 microphone system was primary an underwater sensor, and an underwater communication system was also installed on all boats. No radars were installed on any series of the type.

IX-bis series

Instead of German engines, domestically produced 1D turbo-diesels were installed. Unlike their foreign counterparts, they had (for the same power) slightly higher speeds and were non-reversible. To accommodate turbocompressors and other additional systems, exhaust manifolds were enlarged and various subsystems completely redesigned. In addition, domestically produced batteries were used. The open bridge was redesigned after requests from the crews, returning to traditional closed type. Later in the war boats were equipped with a Burun-M radio director, and the radios received an upgrade. Some boats were also equipped with periscope aerials, allowing the use of radio at periscope depths, and an ASDIC was mounted on most of the boats, significantly increasing patrolling and fire efficiency.

S-56 survives as a museum ship and is on display in Vladivostok.

IX-bis-2 series

Many minor improvements were introduced in this series, mostly to reduce cost and production time. Welding started to be implemented in building the pressure hull as well.

Project 97

A major redesign of the series was started in the early 1940s, including new engines, increased torpedo load and an all-welded pressure hull, but war interrupted the work and all six boats of first series were scuttled soon after laying down.

Postwar

Two submarines of this class, S-52 and S-53, along with two Soviet M-class submarines, and two Template:Sclass-s (under lease, S-121 and S-123) were handed to People's Liberation Army Navy in June 1954, thus becoming the foundation of the submarine force of the People's Republic of China. Two more S-class submarines, S-24 and S-25, were sold to China a few years later. Those purchased by China received new names, but the two leased Shchuka-class submarines did not. S-52, S-53, S-24 and S-25 were renamed in China 11, 12, 13 and 14' respectively.

List

IX series

| Name | Commissioned | Fate |

|---|---|---|

| S-1 | 11 September 1939 | Scuttled at Libava to prevent capture by the Germans, 23 June 1941 |

| S-2 | 23 September 1936 | Sunk by a mine off Märket in Swedish territorial waters, 3 January 1940 |

| S-3 | 8 July 1938 | Sunk in a surface action with E-boats S-60 and S-35, Libava, 24 June 1941 |

IX-bis series

| Name | Commissioned | Fate |

|---|---|---|

| S-4 | 30 October 1939 | Sunk by ramming by German torpedo boat T3 in Danzig Bay, 15 January 1945 |

| S-5 | 30 October 1939 | Sunk by a mine in the Gulf of Finland, 28 August 1941 |

| S-6 | 30 October 1939 | Sunk by a mine off Öland, Sweden, last heard of 6 August 1941 |

| S-7 | 30 June 1940 | Sunk in the Sea of Åland by Finnish submarine Vesihiisi, 21 October 1942 |

| S-8 | 30 Jun 1940 | Sunk by a mine off Öland, Sweden, last heard of 11 October 1941 |

| S-9 | 31 October 1940 | Went missing in August 1943, presumed sunk by mine |

| S-10 | 25 December 1940 | Believed to be sunk by mine in the Irbe Strait around 28 June 1941 |

| S-11 | 27 June 1941 | Sunk by mine off Hiiumaa, Estonia, 2 August 1941 |

| S-12 | 24 July 1941 | Believed to be sunk by mine north of Naissaar, Estonia, last heard of 1 August 1943 |

| S-13 | 31 July 1941 | Decommissioned 7 September 1954 |

| S-27 | Not commissioned | Canceled in July 1941 |

| S-28 | Not commissioned | Canceled in July 1941 |

| S-29 | Not commissioned | Canceled in July 1941 |

| S-30 | Not commissioned | Canceled in July 1941 |

| S-31 | 19 June 1940 | Decommissioned 14 March 1955 |

| S-32 | 19 June 1940 | Believed to be sunk by a German bomber south of Crimea, 26 June 1942 |

| S-33 | 18 November 1940 | Decommissioned 14 March 1955 |

| S-34 | 29 March 1941 | Sunk on 12 November 1941 by a mine of a flanking barrage laid by the Romanian minelayers Amiral Murgescu and Dacia [1] or by the Bulgarian defensive field S-39 [2][3] |

| S-35 | 2 June 1948 | Decommissioned 17 February 1956 |

| S-36 | Not commissioned | The incomplete ship was scuttled to prevent capture by the Germans at Nikolayev, 15 August 1941 |

| S-37 | Not commissioned | The incomplete ship was scuttled to prevent capture by the Germans at Nikolayev, 15 August 1941 |

| S-38 | Not commissioned | The incomplete ship was scuttled to prevent capture by the Germans at Nikolayev, 15 August 1941 |

| S-45 | Not commissioned | Canceled 22 June 1941 |

| S-46 | Not commissioned | Canceled 22 June 1941 |

| S-51 | 30 November 1941 | Decommissioned 7 September 1954, converted into memorial in 1973 |

| S-52 | 9 June 1943 | Stricken from the navy list on 24 August 1954 and transferred to the People's Republic of China |

| S-53 | 30 January 1943 | Stricken from the navy list on 24 August 1954 and transferred to the People's Republic of China |

| S-54 | 31 December 1940 | Went missing, believed to have been sunk by a mine near Kongsfjord, Norway after 5 March 1944 |

| S-55 | 25 July 1941 | Lost to unknown cause, maybe from attack by German subchasers or a mine in December 1943 |

| S-56 | 20 October 1941 | Decommissioned 14 March 1955, turned into museum ship in 1975 |

| S-101 | 15 December 1940 | Stricken from the navy list, 17 February 1956 |

| S-102 | 16 December 1940 | Decommissioned 14 March 1955 |

IX-bis-2 series

| Name | Commissioned | Fate |

|---|---|---|

| S-14 | 21 April 1942 | Stricken from the navy list 9 February 1978 |

| S-15 | 20 December 1942 | Stricken from the navy list 20 June 1956 |

| S-16 | 10 February 1943 | Decommissioned 29 December 1955 |

| S-17 | 20 April 1945 | Decommissioned 29 December 1955 |

| S-18 | 20 June 1945 | Decommissioned 17 February 1956 |

| S-19 | 21 February 1944 | Decommissioned 10 December 1955 |

| S-20 | 19 February 1945 | Decommissioned 17 February 1956 |

| S-21 | 29 March 1946 | Decommissioned 14 March 1959 |

| S-22 | 25 May 1946 | Decommissioned 14 March 1956 |

| S-23 | 27 June 1947 | Decommissioned 18 April 1958 |

| S-24 | 18 December 1947 | Stricken from the navy list on 6 June 1955 and transferred to the People's Republic of China |

| S-25 | 29 March 1948 | Stricken from the navy list on 6 June 1955 and transferred to the People's Republic of China |

| S-26 | 29 March 1948 | Decommissioned 18 April 1958 |

| S-39 | Not commissioned | The incomplete ship was scuttled to prevent capture by the Germans at Nikolayev, 15 August 1941 |

| S-103 | 30 June 1942 | Stricken from the navy list 29 December 1955 |

| S-104 | 22 September 1942 | Decommissioned 14 March 1955 |

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2014) |

- ^ Mikhail Monakov, Jurgen Rohwer, Stalin's Ocean-going Fleet: Soviet Naval Strategy and Shipbuilding Programs 1935-1953, p. 265

- ^ "russian Russian Navy - Soviet Navy - Soviet Union (1918-1991) S-34 (+1941)". wrecksite.eu. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ "(Russian) S-34". sovboat.ru. Retrieved 20 May 2018.