Spanish military orders

The Spanish military orders or Spanish Medieval knights orders are a set of religious-military institutions which arose in the context of the Reconquista, the most important are arising in the 12th century in the Crowns of León and Castile (Order of Santiago, Order of Alcántara and Order of Calatrava) and in 14th century in the Crown of Aragon (Order of Montesa); preceded by many others that have not survived, such as the Aragonese Militia Christi of Alfonso of Aragon and Navarre, the Confraternity of Belchite (founded in 1122) or the Military order of Monreal (created in 1124), which after being refurbished by Alfonso VII of León and Castile took the name of Cesaraugustana and in 1149 with Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona, are integrated into the Knights Templar. The Portuguese Order of Aviz responded to identical circumstances, in the remaining peninsular Christian kingdom.

During the Middle Ages, like elsewhere in the Christianity, in the Iberian Peninsula appeared native Military orders, who, while sharing many similarities with other international orders, also these had own peculiarities due to the special peninsular historical circumstances marked by the confrontation between Muslim and Christians.

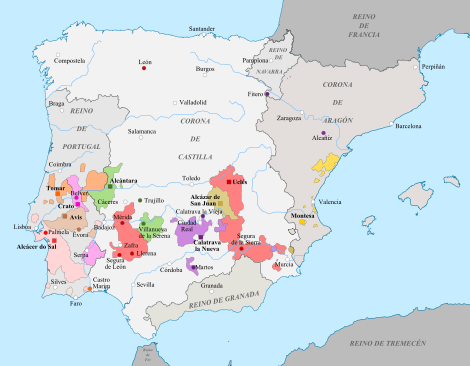

The birth and expansion of these native orders came mostly at the stage of the Reconquista in which were occupied the territories south of the Ebro and Tagus, so their presence in those areas of La Mancha, Extremadura and Sistema Ibérico (Campo de Calatrava, Maestrazgo, etc.) came to mark the main feature of the Repoblación, in large areas in which each Order, through their encomiendas, exercised a political and economic role similar to that of manor feudal. The presence of other foreign military orders, such as the Templar or the Saint John was simultaneously, and in the case of the Knights Templar, their suppression in the 14th century benefited significantly to the Spanish.

The social implementation of the military orders between the noble families was very significant, extending even through related female orders (Comendadoras de Santiago and others similar).

After the turbulent period of the late medieval crisis, in which the position of Grand Master of the orders was the subject of violent disputes between the aristocracy, the monarchy and the favourites (infantes of Aragon, Álvaro de Luna, etc.); Ferdinand II of Aragon, in the late 15th century managed to politically neutralize to obtain the papal concession of the unification in the person of that position for all of them, and its joint inheritance for its heirs, the kings of the later Spanish Catholic monarchy, that administered through the Royal Council of the Military Orders.

Gradually lost any military function along the Antiguo Régimen, the territorial wealth of the military orders was the subject of confiscation in the 19th century, being reduced these thereafter to the social function of representing, as honorary positions, an aspect of the noble status.[1]

Birth and evolution

Although the appearance of the Hispanic military orders can be interpreted as pure imitation of the international arisen following the Crusades, both its birth and its subsequent evolution have distinctive features, as they played a leading role in the struggle of Christian kingdoms against the Muslims, in the repopulation of large territories, especially between the Tagus and the Guadalquivir and became a political and economic force of the first magnitude, besides having great role in the noble struggles held between the 13th and 15th centuries, when finally the Catholic Monarchs managed to gain its control.

For the Arabists, the birth of the Spanish military orders was inspired by the Muslims ribat, but other authors believe that its appearance was the result of a merger of confraternities and council militias tinged with religiosity, by absorption and concentration gave rise to the large orders at a time when the struggle against the Almohad power required every effort by the Christian side.

Traditionally it is accepted that the first to appear was that of Order of Calatrava, born in that village of the Castilian kingdom in 1158, followed by that of Order of Santiago, founded in Cáceres, in the Leonese kingdom, in 1170. Six years later was created the Order of Alcántara, initially called ¨of San Julián del Pereiro¨. The last to appear was the Order of Montesa it did later on, during the 14th century, in the Crown of Aragon due to the dissolution of the Order of the Templar.

Hierarchical organization

Imitating the international orders, the Spanish adopted their organization. The master was the highest authority of the order, with an almost absolute power, both militarily, and politically or religiously. It was chosen by the council, made up of thirteen friars, where it comes to its components the name of "Thirteens". The office of Master is life-time and in his death the Thirteen, convened by the greater prior of the order, choose the new. It should be the removal of the master by incapacity or pernicious conduct for the order. To carry out it needed the agreement of its governing bodies: council of the thirteen, "greater prior" and "greater convent".

The General Chapter is a kind of representative assembly that controls the entire order. What are the thirteen, the priors of all the convents and all commanders. It should meet annually a certain day in the greater convent, although in the practice these meetings were held where and when the master wanted.

In each kingdom there was a "greater commander", based in a town or fortress. The priors of each convent were elected by the canons, because it must bear in mind that within the orders were freyles milites (knights) and freyles clérigos, professed monks who taught and administering the sacraments.

Territorial organization

the end of 15th century:

Residence of the Grand Master

Residence of the Grand MasterBecause of their dual nature as military and religious institutions, territorially the orders develop a separate double organization for each of these areas, although sometimes not completely detached.

In the political-military these were divided into "major encomiendas" there greater encomienda by each peninsular kingdom in which was present the order in question. In front of them was the main commander. It was followed by the encomiendas, which were a set of goods, not always territorial nor grouped, but generally constituted territorial demarcations. The encomiendas were administered by a commander. The fortresses, that by any type of cause were not under the command of the commander, were headed by an alcaide appointed by him.

Religiously were organized by convents, existing a main convent, which was the headquarters of the order. In the case of the Order of Santiago was based in Uclés, after the rifts of the order with the Leonese monarch Ferdinand II. The Order of Alcántara had it in the Extremaduran village that gave it its name.

The convents were not only places where lived the professed monks, but constituted priories, religious territorial demarcations where the respective priors with the time had the same powers as the bishoprics, resulting in the military orders were subtracted to the episcopal power in extensive territories.

Army

The command of the army it exercised the highest dignities of each order. At the apex the master, followed by the main commanders. The figure of alférez was highlighted at beginning, but in the Middle Ages had disappeared. The command of the fortresses was in the hands of the commander or an alcaide appointed by him.

The recruitment was used to do by encomiendas, contributing presumably each with a number of lances or men related to the economic value of the demarcation.

Of note is the surprising bellicosity of the orders and its rigorous promise to fight the infidel, which often manifested itself in the continuation of authentic "private wars" against the Muslims when, for various reasons, the Christian kings gave up the struggle, because signing truces or to direct its military actions in other ways, as when Ferdinand III of Castile, crowned king of León, abandoned the interests of this kingdom to pursue the conquest of Andalusia in favor of the Crown of Castile.

Repopulation and social policy

To be important the military role played by the military orders, was no less its repopulater, economic and social role. Because not enough to wrest territories to the enemy if they are not populated enough to occupy and use it, thus facilitating their defense.

The orders received large tracts of land, whose repopulation reported it great political and economic power. To attract people to the acquired lands, they used similar methods to those used by other institutions. One was to grant fueros to the villages of their jurisdiction that made them attractive to people of the north. Generally it copied the models of fueros more generous, such as that of Cáceres or of Sepúlveda. An example of this generosity was the tax exemptions by marriage, taken from the Fuero of Usagre.

Moreover, some unproductive land were useless, so they worried about its economic development. In this sense, besides the advantages given to the new settlers, as the donations of disused public lands, were achieved fairs to their villages or were carried out important infrastructure works on the network communications. The fairs had the advantage of being tax-free, which fomented trade, which was also driven by improving communications (bridges, roads, etc.).

Relations with other institutions

The relations of the Hispanic military orders with other powers and institutions were diverse. Generally enjoyed the papal support, because they constituted a solid basis for the reconquista and depended directly on its authority. The Popes granted episcopal attributions to the priors of the orders in their struggle with the bishops, giving them greater independence.

As for the relationship with the kings, followed several stages. At first the monarchs impelled the Orders because they came to regard the "most precious jewel" of their crowns. Conscious of its enormous potential in the reconquest task, and later repopulation, the kings fostered it and introduced in their respective realms. As with Alfonso of Aragon and Navarre, when in 1122 he founded the confraternity of Belchite, or Alfonso VIII of Castile and Alfonso IX of León, who offered possessions to the orders of Santiago and Calatrava, respectively, lure it to their kingdoms. Although the royal donations for the most part were constituted by territories, to make them effective in the fight against Muslims, also received from the monarchs other donations not strictly military or political, such as those motivated by reasons of charity, mercy, hospitality and friendship. Often the favor of the kings also it manifested in the numerous lawsuits that arose with other powers, which generally the monarchs ruled in favor of the orders. The tax privileges or other were equally frequent, which sometimes caused the irritation of the concejos of realengo, whose neighbors paid tribute to a greater extent.

In exchange for the royal favor, the orders carried out the missions that were entrusted and were loyal to the monarchs, whose side were placed since the late 13th century the noble disputes became so frequent. Thereafter, the kings took conscience of the enormous power of the orders and the danger that could suppose having them against, hence with Alfonso XI of Castile began a struggle to get its control, to through the designation of the master. This struggle continued throughout the High Middle Ages until the absolute attainment of the royal purposes by the Catholic Monarchs, who managed to hold the mastership of all of them in perpetuity. With their descendants this mastership became hereditary.

More problematic was the relationship with the concejos of realengo (kind of councils of municipalities into royal territory), especially those endowed with extensive domains of difficult control and occupation. Often suffered the predation of unpopulated areas by the orders until the kings ended the usurpations, but from the 14th century these councils suffered the same predation by lay lords. There were also disputes with neighboring, sometimes prolonged and even so vehement that these produced physical confrontations.

Equally diverse resulted the relationship with the rest of the clergy. This contest of it was fundamental for the configuration of the orders, as happened with the support of the Archbishop of Santiago de Compostela regarding the order of Santiago or the bishop of Salamanca regarding that of the Alcántara. But later there was everything, from pious donations to endless lawsuits and skirmishes, and even some feat of arms, like the attack to the bishops of Cuenca and Sigüenza by the Santiago's commander of Uclés. And the tensions with the bishops were frequent in the struggle for the ecclesiastical jurisdiction, which were subtracted the priors, who finally received the papal support.

The brotherhood and coordination were the dominant attitudes in the relations between orders. Calatrava and Alcántara were united by relations of affiliation, without incurring lack of autonomy of Alcántara. There were agreements between orders of mutual aid and sharing the archieved. Even agreements such as the tripartite of friendship, mutual defense, coordination and centralization signed in 1313 by Santiago, Calatrava and Alcántara.

Dissolution

The Military Orders were dissolved the April 29 of 1931 by mandate of the Republican government.

During the Spanish Civil War were murdered many of their knights, killing nineteen of the Military Order of Santiago, fifteen of the Military Order of Calatrava, five of the Military Order of Alcántara and four of the Military Order of Montesa.

The balance of Knights of 1931 to 1935 is as follows:

- Military Order of Santiago, 68 of 116.

- Military Order of Calatrava, 89 of 139.

- Military Order of Alcántara, 19 of 42.

- Military Order of Montesa, 51 of 70.

In 1985 lived only 19 knights who professed before 1931.

After the Spanish Civil War began talks with the dictator Francisco Franco, inviting to the bishop-prior Emeterio Echeverría Barrena, did not get any results, so over these years they subsitieron marginally, until April 2 of 1980 were recorded separately on the record of associations of Civil Government of Madrid. The May 26 of that year are registered as federation. The Order of Santiago, along with those of Calatrava, Alcántara and Montesa, were reinstated as civil associations in the reign of Juan Carlos I with the character of honorable and religious noble organization and as such remain today.

The 9 April 1981, and after fifty years of long vacant, the King of Spain, Juan Carlos I, names to his father Juan of Bourbon President of the Royal Council of the Military Orders. Since the April 28, 2014 holds this presidency Don Pedro of Bourbon, Duke of Noto.

List

- Medieval knights orders founded in Spain (by alphabetic order)

- Female orders

Mostly were honorific orders in payment of efforts by warrior girls attacking Muslims or English, and their high contribution to the conquest of cities, some came to become in reconquista's female military orders.[17]

| Emblem | Name | Founded | Founder | Origin | Recognition | Protection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female order of the Band | 1387 | John I of Castile | Palencia, Castile and León (Crown of Castile) | Crown of Castile (1387- )[18] | ||

| Female order of the Hatchet | 1149 | Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona | Tortosa, Catalonia (County of Barcelona) | County of Barcelona (1149- )[19] | ||

| Order of Santiago | 1151 | Ferdinand II of León and Pedro Suárez de Deza | Uclés, Castile-La Mancha (Kingdom of Castile) and León, Castile and León (Kingdom of León) | July 5, 1175 by Pope Alexander III, Pope Urban III, Pope Innocent III | Kingdom of León (1158- ), Kingdom of Castile (1158- )[20] |

- Both Medieval naval and knights orders, fulfilling dual function, but mainly naval

| Emblem | Name | Founded | Founder | Origin | Recognition | Protection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Order of Saint Mary of Spain | 1270 | Alfonso X of Castile | Cartagena, Region of Murcia (Crown of Castile) | Crown of Castile (1177- )[21] |

See also

References

- ^ Miguel Artola, Enciclopedia de Historia de España, Alianza Editorial, tomo 5 pg. 892

- ^ "The militar order of Alcántara", Heraldaria.com

- ^ "MÁS SOBRE LA ORDEN DE LA BANDA", aristo.hypotheses.org

- ^ "The creation of the militar confraternity of Belchite", Basque digital memory (pdf file)

- ^ Book: Hispania incognita, Publisher: TEMPLESPAÑA

- ^ "The militar order of Calatrava", heraldaria.com

- ^ "Orden del Armiño.", enciclonet 3.0

- ^ "La Orden de Caballería de la Jarra y el Grifo celebra su día grande en Medina", El Norte de Castilla (newspaper)

- ^ Manuel Fuertes de Gilbert y Rojo (2007). Corporate peerage in Spain: Nine centuries of noble entities.. Ediciones Hidalguía, Madrid. pp. 60 and follows. ISBN 978-84-89851-57-3.

- ^ "La orden militar de Montesa", heraldaria.com

- ^ "The Monastic Military Order of Jerusalem and St. Mary of Mountjoy.", arcomedievo.es

- ^ "ORDEN DE LA PALOMA.- España", ordenbonariacolegioheraldico.blogspot.com

- ^ "ORDEN DE LA RAZON.- España", ordenbonariacolegioheraldico.blogspot.com

- ^ "La Orden de San Jorge", heraldaria.com

- ^ "ORDEN DE LA PALOMA.- España", ordenbonariacolegioheraldico.blogspot.com

- ^ "LAS DIVISAS DEL REY: ESCAMAS Y RISTRES EN LA CORTE DE JUAN II DE CASTILLA", Álvaro Fernández de Córdova Miralles, (pdf file)

- ^ [(http://www.erroreshistoricos.com/curiosidades-historicas/militar/1485-las-mujeres-en-las-ordenes-de-caballeria.html "THE WOMEN IN THE KNIGHT ORDERS"]

- ^ [(http://www.erroreshistoricos.com/curiosidades-historicas/militar/1485-las-mujeres-en-las-ordenes-de-caballeria.html "THE WOMEN IN THE KNIGHT ORDERS"]

- ^ "Hacha" dibujoheraldico.blogspot.com (in Spanish)

- ^ "ORDEN DE LA PALOMA.- España", ordenbonariacolegioheraldico.blogspot.com

- ^ "La orden militar de Santa María de España", http://historiadealcaladelosgazules.blogspot.com