Sumatran tiger

| Sumatran tiger | |

|---|---|

| |

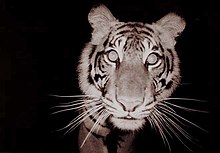

| Sumatran tiger in the Tierpark Berlin | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. t. sondaica

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera tigris sondaica (Temminck, 1844)

| |

| |

| Distribution map | |

| Synonyms | |

|

formerly P. t. sumatrae Pocock, 1929 | |

The Sumatran tiger is a Panthera tigris sondaica population in the Indonesian island of Sumatra.[2] This population was listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List in 2008, as it was estimated at 441 to 679 individuals, with no subpopulation larger than 50 individuals and a declining trend.[1]

The Sumatran tiger is the only surviving tiger population in the Sunda Islands, where the Bali and Javan tigers are extinct.[3] Sequences from complete mitochondrial genes of 34 tigers support the hypothesis that Sumatran tigers are diagnostically distinct from mainland subspecies.[4]

In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the Cat Specialist Group revised felid taxonomy and now recognizes the living and extinct tiger populations in Indonesia as P. t. sondaica.[2]

Characteristics

Pocock first described the Sumatran tiger on the basis of several skull, pelage, and striping features, which are distinct from the Bengal and Javan tigers. It is darker in fur colour and has broader stripes than the Javan tiger.[5] Stripes tend to dissolve into spots near their ends, and on the back, flanks and hind legs are lines of small, dark small spots between regular stripes.[6][7] The frequency of stripes is higher than in other subspecies.[8] Males have a prominent ruff, which is especially marked in the Sumatran tiger.[9]

The Sumatran tiger is one of the smallest tigers, and about the size of big leopards and jaguars. Males weigh 100 to 140 kg (220 to 310 lb) and measure 2.2 to 2.55 m (87 to 100 in) in length between the pegs with a greatest length of skull of 295 to 335 mm (11.6 to 13.2 in). Females weigh 75 to 110 kg (165 to 243 lb) and measure 2.15 to 2.30 m (85 to 91 in) in length between the pegs with a greatest length of skull of 263 to 294 mm (10.4 to 11.6 in).[6]

Charles Frederick Partington wrote that Sumatran and Javan tigers were strong enough to break legs of horses or buffaloes with their paws, even though they were not as heavy as Bengal tigers.[10]

Evolution

Analysis of DNA is consistent with the hypothesis that Sumatran tigers became isolated from other tiger populations after a rise in sea level that occurred at the Pleistocene to Holocene border about 12,000–6,000 years ago. In agreement with this evolutionary history, the Sumatran tiger is genetically isolated from all living mainland tigers, which form a distinct group closely related to each other.[4]

Distribution and habitat

Sumatran tigers persist in isolated populations across Sumatra.[11] They occupy a wide array of habitats, ranging from sea level in the coastal lowland forest of Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park on the southeastern tip of Lampung Province to 3,200 m (10,500 ft) in mountain forests of Gunung Leuser National Park in Aceh Province. They have been repeatedly photographed at 2,600 m (8,500 ft) in a rugged region of northern Sumatra, and are present in 27 habitat patches larger than 250 km2 (97 sq mi).[12]

In 1978, the Sumatran tiger population was estimated at 1,000 individuals,[13] based on responses to a questionnaire survey.[14] In 1985, a total of 26 protected areas across Sumatra containing about 800 tigers were identified.[15] In 1992, an estimated 400–500 tigers lived in five national parks and two protected areas.[16]

At that time, the largest population, comprising 110–180 individuals, was reported from the Gunung Leuser National Park.[17] However, a more recent study shows that the Kerinci Seblat National Park in central Sumatra has the highest population of tigers on the island, estimated to be 165–190 individuals. The park also was shown to have the highest tiger occupancy rate of the protected areas, with 83% of the park showing signs of tigers.[18] More tigers are in the Kerinci Seblat National Park than in all of Nepal, and more than in China, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam combined.[19][20]

Ecology and behaviour

Sumatran tigers strongly prefer uncultivated forest and make little use of plantations of acacia and oil palm even if these are available. Within natural forest areas, they tend to use areas with higher elevation, lower annual rainfall, farther from forest edge, and closer to forest centres. They prefer forest with dense understory cover and steep slope, and they strongly avoid forest areas with high human influence in the forms of encroachment and settlement. In acacia plantations, they tend to use areas closer to water, and prefer areas with older plants, more leaf litter, and thicker subcanopy cover. Tiger records in oil palm plantations and in rubber plantations are scarce. The availability of adequate vegetation cover at the ground level serves as an environmental condition fundamentally needed by tigers regardless of the location. Without adequate understory cover, tigers are even more vulnerable to persecution by humans. Human disturbance-related variables negatively affect tiger occupancy and habitat use. Variables with strong impacts include settlement and encroachment within forest areas, logging, and the intensity of maintenance in acacia plantations.[21] Camera trapping surveys conducted in southern Riau revealed an extremely low abundance of potential prey and a low tiger density in peat swamp forest areas. Repeated sampling in the newly established Tesso Nilo National Park documented a trend of increasing tiger density from 0.90 individuals per 100 km2 (39 sq mi) in 2005 to 1.70 individuals per 100 km2 (39 sq mi) in 2008.[22]

In the Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park, nine prey species larger than 1 kg (2.2 lb) of body weight were identified including great argus, pig-tailed macaque, Malayan porcupine, Malayan tapir, banded pig, greater and lesser mouse-deer, Indian muntjac, and Sambar deer.[11] As Sumatran tigers are apex predators in their habitat, the continuing decline in their population numbers is likely to destabilize food chains and lead to various ecosystem changes when these prey species experience a release from predation pressure and increase in numbers.[23]

Threats

Major threats include habitat loss due to expansion of palm oil plantations and planting of acacia plantations, prey-base depletion, and illegal trade primarily for the domestic market.[1]

Tigers need large contiguous forest blocks to thrive.[21] Between 1985 and 1999, forest loss within Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park averaged 2% per year. A total of 661 km2 (255 sq mi) of forest disappeared inside the park, and 318 km2 (123 sq mi) were lost in a 10-km buffer, eliminating forest outside the park. Lowland forest disappeared faster than montane forest, and forests on gentle slopes disappeared faster than forests on steep slopes. Most forest conversion resulted from agricultural development, leading to predictions that by 2010, 70% of the park will be in agriculture. Camera-trap data indicated avoidance of forest boundaries by tigers. Classification of forest into core and peripheral forest based on mammal distribution suggests that by 2010, core forest area for tigers will be fragmented and reduced to 20% of remaining forest.[24]

Kerinci Seblat National Park, which has the largest recorded population of tigers, is suffering a high rate of deforestation in its outer regions. Drivers are an unsustainable demand for natural resources created by a human population with the highest rate of growth in Indonesia, and a government initiative to increase tree-crop plantations and high-intensity commercial logging, ultimately promoting forest fires. The majority of the tigers found in the park were relocated to its center where conservation efforts are focused, but issues in the lowland hill forests of the outskirts remain. While being highly suitable tiger habitat, these areas are also heavily targeted by logging efforts, which substantially contributes to declines in local tiger numbers.[25] A major driver for forest clearance are oil-palm plantations, which form a major part of Indonesia’s economy. Global consumption of palm oil has increased five-fold over the past decade, presenting a challenge for many conservation efforts.[26]

The expansion of plantations is also increasing greenhouse-gas emissions, playing a part in anthropogenic climate change, thus further adding to environmental pressures on endangered species.[27] Climate-based movement of tigers northwards may lead to increased conflict with human populations. From 1987 to 1997, Sumatran tigers reportedly killed 146 people and at least 870 livestock. In West Sumatra, Riau, and Aceh, a total of 128 incidents were reported; 265 tigers were killed and 97 captured in response, and 35 more tigers were killed from 1998 to 2002. From 2007 to 2010, the tigers caused the death of 9 humans and 25 further tigers were killed.[28]

Despite being given full protection in Indonesia and internationally, tiger parts are still found openly in trade in Sumatra. In 1997, an estimated 53 tigers were reported to have been poached and their parts sold throughout most of northern Sumatra. Numbers for all of Sumatra are likely to be higher. Many of the tigers were also found to have been killed by farmers claiming that the tigers were endangering their livestock. These tigers were then sold to gold shops, souvenir shops, and pharmacies.[29] Farmers are probably the main hunters of tigers in Sumatra.[29] In 2006, surveys were conducted over a seven-month period in 28 cities in seven Sumatran provinces and nine seaports. A total of 326 retail outlets were surveyed, and 33 (10%) were found to have tiger parts for sale, including skins, canines, bones, and whiskers. Tiger bones demanded the highest average price of US$116 per kg, followed by canines. Some evidence shows that tiger parts are smuggled out of Indonesia. In July 2005, over 140 kg of tiger bones and 24 skulls were confiscated in Taiwan in a shipment from Jakarta.[30]

Conservation

Panthera tigris is listed on CITES Appendix I. Hunting is prohibited in Indonesia.[9]

In 1994, the Indonesian Sumatran Tiger Conservation Strategy addressed the potential crisis that tigers faced in Sumatra. The Sumatran Tiger Project (STP) was initiated in June 1995 in and around the Way Kambas National Park to ensure the long-term viability of wild Sumatran tigers and to accumulate data on tiger life-history characteristics vital for the management of wild populations.[31] By August 1999, the teams of the STP had evaluated 52 sites of potential tiger habitat in Lampung Province, of which only 15 were intact enough to contain tigers.[32] In the framework of the STP, a community-based conservation programme was initiated to document the tiger-human dimension in the park to enable conservation authorities to resolve tiger-human conflicts based on a comprehensive database rather than anecdotes and opinions.[33]

In 2007, the Indonesian Forestry Ministry and Safari Park established cooperation with the Australia Zoo for the conservation of Sumatran tigers and other endangered species. The program includes conserving Sumatran tigers and other endangered species in the wild, efforts to reduce conflicts between tigers and humans, and rehabilitating Sumatran tigers and reintroducing them to their natural habitat. One hectare of the 186-hectare Taman Safari is the world's only Sumatran tiger captive-breeding center that also has a sperm bank.[34]

Indonesia's struggle with conservation has caused an upsurge in political momentum to protect and conserve wildlife and biodiversity. In 2009, Indonesia's president made a commitment to substantially reduce deforestation and policies across the nation[35] requiring spatial plans that would be environmentally sustainable at national, provincial and district levels.[35] Over the past decade, about US$210 million have been invested into the tiger law-enforcement activities that support forest ranger patrols, as well as the implementations of front-line law-enforcement activities by the Global Tiger Recovery Plan, which aims to double the number of wild tigers by 2020.[36]

A 2008 study used simple spatial analyses on readily available datasets to compare the distribution of five ecosystem services across tiger habitat in central Sumatra.[35] The study examined a decade of law-enforcement patrol data within a robust mark and recapture statistical framework to assess the effectiveness of law-enforcement interventions in one of Asia’s largest tiger habitats.[35] In 2013–2014, Kerinci Seblat experienced an upsurge in poaching, with the highest annual number of snare traps being removed for a patrol effort similar to previous years. Evidence is scarce and misunderstood on whether the strategies implemented to diminish poaching are succeeding despite the investment of millions of dollars annually into conservation strategies.

A 2010 study examined a different strategy for promoting Sumatran tiger conservation while at the same time deriving a financial profit, by promoting "tiger-friendly" vegetable margarine as an alternative to palm oil. The study concluded that consumers were willing to pay a premium for high-quality margarine connected with tiger conservation.[37]

A 110,000-acre conservation area and rehabilitation center, Tambling Wildlife Nature Conservation, has been set up on the edge of a national park on the southern tip of Sumatra (Lampung).[38] On 26 October 2011, a tigress that had been captured with an injured leg in early October delivered three male cubs in a temporary cage while waiting for release after her recovery.[39]

Due to Indonesia's need for more sanctuaries for the Sumatran tiger, Sumatran elephant, Sumatran orangutan and Sumatran rhinoceros, the government opened the Batu Nanggar Sanctuary for the Sumatran tiger at North Padang Lawas Regency, North Sumatra in November 2016.[40]

In captivity

On 3 February 2014, three Sumatran tiger cubs were born to a five-year-old tigress in London Zoo's Tiger Territory, a £3.6m facility to encourage endangered subspecies of tiger to breed.[41][42]

On 26 June 2016, two tiger cubs were born at London Zoo after a 108-day pregnancy, the first cub was delivered at 9:19 am, and the second shortly after at 10:02 am.[43]

In August 2017, two Sumatran tiger cubs (Anala and Jeda) were born from mother, Sohni and father, Malosi at Disney's Animal Kingdom in Orlando, Florida.[44]

See also

- Bornean tiger

- Caspian tiger

- Indochinese tiger

- Malayan tiger

- Siberian tiger

- South China tiger

- Ngandong tiger

- Trinil tiger

- Wanhsien tiger

- Physical comparison of tigers and lions

References

- ^ a b c Template:IUCN

- ^ a b Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11).

- ^ Mazák, J. H.; Groves, C. P. (2006). "A taxonomic revision of the tigers (Panthera tigris)" (PDF). Mammalian Biology. 71 (5): 268–287. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2006.02.007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-13.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Cracraft, J.; Feinstein, J.; Vaughn, J.; Helm-Bychowski, K. (1998). "Sorting out tigers (Panthera tigris): Mitochondrial sequences, nuclear inserts, systematics, and conservation genetics" (PDF). Animal Conservation. 1 (2): 139–150. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.1998.tb00021.x.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1929). "Tigers". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 33: 505–541.

- ^ a b Mazák, V. (1981). "Panthera tigris" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 152 (152): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504004. JSTOR 3504004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-09.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mazák, J.H.; Groves, C.P. (2006). "A taxonomic revision of the tigers (Panthera tigris) of Southeast Asia". Mammalian Biology-Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 71 (5): 268–287. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2006.02.007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Kitchener, A. (1999). "Tiger distribution, phenotypic variation and conservation issues". In Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S., Jackson, P. (eds.). Riding the Tiger. Tiger Conservation in human-dominated landscapes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–39. ISBN 0-521-64057-1.

{{cite book}}:|archive-url=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b Nowell, K., Jackson, P. (1996). Tiger Panthera tigris (Linnaeus 1758) in: Wild Cats: status survey and conservation action plan. IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland

- ^ Partington, C. F. (1835). "Felis, the cat tribe". The British cyclopæedia of natural history. Orr & Smith.

- ^ a b O’Brien, T. G.; Kinnard, M. F.; Wibisono, H. T. (2003). "Crouching tigers, hidden prey: Sumatran tiger and prey populations in a tropical forest landscape". Animal Conservation. 6 (2): 131–139. doi:10.1017/S1367943003003172.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Wibisono, H. T.; Pusarini, W. (2010). "Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae): A review of conservation status". Integrative Zoology. 5 (4): 313–23. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00219.x. PMID 21392349.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Poston, Lee (2013-10-29). "The final days of the Sumatran tiger?". CNN. Archived from the original on 2013-11-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Borner, M. (1978). "Status and conservation of the Sumatran tiger". Carnivore. 1 (1): 97–102.

- ^ Santiapillai, C., Ramono, W. S. (1987). Tiger numbers and habitat evaluation in Indonesia, pp. 85–91 in: Tilson, R. L., Seal, U. S. (eds.) Tigers of the World: The Biology, Biopolitics, Management, and Conservation of an Endangered Species. Noyes Publications, New Jersey, ISBN 0815511337.

- ^ Tilson, R. L., Soemarna, K., Ramono, W. S., Lusli, S., Traylor-Holzer, K., Seal, U. S. (1994). Sumatran Tiger Populations and Habitat Viability Analysis. Indonesian Directorate General of Forest Protection and Nature Conservation, and IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, Apple Valley.

- ^ Griffiths, M. (1994). Population density of Sumatran tigers in Gunung Leuser National Park, pp. 93–102 in: Tilson, R., Soemarna, K., Ramono, W. S., Lusli, S., Traylor-Holzer, K., Seal, U. (eds.) Sumatran Tiger Population and Habitat Viability Analysis Report. Directorate of Forest Protection and Nature Conservation and IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, Apple Valley, Minnesota.

- ^ Wibisono HT, Linkie M, Guillera-Arroita G, Smith JA, Sunarto, et al. (2011). Gratwicke B (ed.). "Population Status of a Cryptic Top Predator: An Island-Wide Assessment of Tigers in Sumatran Rainforests". PLoS ONE. 6 (11): e25931. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625931W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025931. PMC 3206793. PMID 22087218.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kutarumalos, Ali (2011-04-28). "Road-building plans threaten Indonesian tigers". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 2014-01-02.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "No humour, not this time – 26th of April 2011". 21st Century Tiger. 2011-04-26. Archived from the original on 2014-01-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Sunarto, S.; Kelly, M. J.; Parakkasi, K.; Klenzendorf, S.; Septayuda, E.; Kurniawan, H. (2012). Gratwicke, Brian (ed.). "Tigers Need Cover: Multi-Scale Occupancy Study of the Big Cat in Sumatran Forest and Plantation Landscapes". PLoS ONE. 7 (1): e30859. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...730859S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030859. PMC 3264627. PMID 22292063.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Sunarto, S. (2011), Ecology and restoration of Sumatran tigers in forest and plantation landscapes (PhD dissertation), Virginia Tech, archived from the original on 2013-05-26

- ^ "Periyar Tiger Reserve". www.periyartigerreserve.org. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ Kinnaird, M. F.; Sanderson, E. W.; O'Brien, T. G.; Wibisono, H.; Woolmer, G. (2003). "Deforestation trends in a tropical landscape and implications for forest mammals" (PDF). Conservation Biology. 17: 245–257. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.02040.x.

- ^ Linkie, Matthew (2003). "Habitat Destruction and Poaching Threaten the Sumatran Tiger in Kerinci Seblat National Park, Sumatra". Oryx. 37. doi:10.1017/s0030605303000103.

- ^ Campbell, Charlie. "Palm Oil Is Killing the Sumatran Tiger". Time. No. 0040-718X. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ Aldred, Jessica. "Sumatran deforestation driving climate change and species extinction, report warns". the Guardian. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ^ Wibisono, Hariyo T.; Pusparini, Wulan (2010-12-01). "Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae): A review of conservation status". Integrative Zoology. 5 (4): 313–323. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00219.x. PMID 21392349.

- ^ a b Plowden, Campbell (1997). "The Illegal Market in Tiger Parts in Northern Sumatra, Indonesia". Oryx. 31: 59. doi:10.1017/s0030605300021918.

- ^ Ng, J. and Nemora. (2007). Tiger trade revisited in Sumatra, Indonesia. Traffic Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia.

- ^ Franklin, N., Bastoni, Sriyanto, Siswomartono, D., Manansang, J. and R. Tilson (1999). Last of the Indonesian tigers: a cause for optimism, pp. 130–147 in: Seidensticker, J., Christie, S. and Jackson, P. (eds). Riding the tiger: tiger conservation in human-dominated landscapes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, ISBN 0521648351.

- ^ Tilson, R. (1999). Sumatran Tiger Project Report No. 17 & 18: July − December 1999. Grant number 1998-0093-059. Indonesian Sumatran Tiger Steering Committee, Jakarta.

- ^ Nyhus, P., Sumianto and R. Tilson (1999). The tiger-human dimension in southeast Sumatra, pp. 144–145 in: Seidensticker, J., Christie, S. and Jackson, P. (eds). Riding the tiger: tiger conservation in human-dominated landscapes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, ISBN 0521648351.

- ^ Boediwardhana, Wahyoe (2012-12-15). "Sumatran tiger sperm bank". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 2014-10-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Bhagabati, Nirmal K.; Ricketts, Taylor; Sulistyawan, Thomas Barano Siswa; Conte, Marc; Ennaanay, Driss; Hadian, Oki; McKenzie, Emily; Olwero, Nasser; Rosenthal, Amy (2014-01-01). "Ecosystem services reinforce Sumatran tiger conservation in land use plans". Biological Conservation. 169: 147–156. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2013.11.010.

- ^ Linkie, Matthew; Martyr, Deborah J; Harihar, Abishek; Risdianto, Dian; Nugraha, Rudijanta T; Maryati; Leader-Williams, Nigel; Wong, Wai-Ming (2015-08-01). "Safeguarding Sumatran tigers: evaluating effectiveness of law enforcement patrols and local informant networks". Journal of Applied Ecology. 52 (4): 851–860. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12461.

- ^ Bateman, Ian J.; Fisher, Brendan; Fitzherbert, Emily; Glew, David; Naidoo, Robin (2010-04-01). "Tigers, markets and palm oil: market potential for conservation". Oryx. 44 (2): 230–234. doi:10.1017/S0030605309990901.

- ^ Williams, Ian (2010-11-19). "On the prowl for man-eating tigers". NBC News. Archived from the original on 2013-11-13.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tambling Ketambahan Tiga Anak Harimau". Media Indonesia. 2011-11-01. Archived from the original on 2012-04-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) English translation at Google Translate - ^ Apriadi Gunawan; Jon Afrizal (2016). "Sumatran tigers need more sanctuaries: Government".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sumatran tiger cubs born at London Zoo". BBC News. 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-03-25. Retrieved 2015-01-15.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Aldred, J. (2014). "Sumatran tiger triplets born at London zoo". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2014-10-24. Retrieved 2015-01-15.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "ZSL London Zoo welcomes tiger cub twins". Pressat.

- ^ "Disney's Animal Kingdom Celebrates Birth of Critically Endangered Sumatran Tiger Cubs". Disney Parks Blog.

External links

- "Species portrait Panthera tigris". International Union for Conservation of Nature/SSC Cat Specialist Group. Archived from the original on 2014-11-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) and "short portrait P. t. sumatrae". International Union for Conservation of Nature/SSC Cat Specialist Group. Archived from the original on 2014-12-13.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Sumatran Tiger Trust Conservation Program". World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Archived from the original on 2015-03-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Tiger Facts − Sumatran Tiger". The Tiger Foundation. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Overweight captive Sumatran tiger (338 lb (153 kg)) at the National Zoological Park (United States)

- Indonesia races to catch tiger alive as villagers threaten to ‘kill the beast’