Tell Sabi Abyad

تل صبي أبيض | |

Excavations at Tell Sabi Abyad. | |

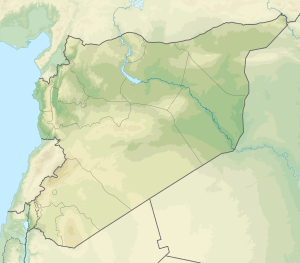

| Location | Syria |

|---|---|

| Region | Balikh River valley |

| Coordinates | 36°30′14″N 39°05′35″E / 36.504°N 39.093°E |

| Type | settlement |

| Area | 11 hectares (27 acres), 15–16 hectares (37–40 acres) (with city walls), 4 hectares (9.9 acres) (outer town) |

| Height | 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) |

| History | |

| Material | clay, limestone |

| Founded | c. 7550 BC |

| Abandoned | c. 1250 BC |

| Periods | Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, Neolithic, Transitional Neolithic-Halaf, Early Bronze Age-Halaf, Middle Assyrian period |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 2002–ongoing |

| Archaeologists | C. Castel, N. Awad, Peter Akkermans |

| Condition | ruins |

| Management | Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums |

| Public access | Yes |

Tell Sabi Abyad (Arabic: تل صبي أبيض) is an archaeological site in the Balikh River valley in northern Syria. It lies about 2 kilometers south of Tell Hammam et-Turkman.The site consists of four prehistoric mounds that are numbered Tell Sabi Abyad I to IV. Extensive excavations showed that these sites were inhabited already around 7500 to 5500 BC, although not always at the same time; the settlement shifted back and forth among these four sites.[1]

The earliest pottery of Syria was discovered here; it dates at ca. 6900-6800 BC, and consists of mineral-tempered, and sometimes painted wares.

Excavations

[edit]Excavations, by Peter Akkermans under the auspices of Leiden University, began with a sounding on the Tell Sabi Abyad I in 1986.[2] Actual excavations on the main mound began with a field season in 1988 which focused on the Neolithic areas. Among the finds were several labrets and stamp seals as well as over 1000 unbaked clay sling missiles stored in a container.[3] Two more seasons, in 1991 and 1992, were conducted on the main mound, concentrating on the Middle Assyrian remains at the summit.[4] Surveys were conducted at the fourth mound, but excavations were not possible because of its use as a local cemetery.[5] Further excavations were conducted from 1994 to 1999.[6] After a pause field work continued in 2001–2003.[7] In 2005 and 2010 soundings were conducted on Tell Sabi Abyad III. Excavation ceased then with the outbreak of warfare.[8]

Ceramics

[edit]It was discovered that around 6700 BC, pottery was already mass-produced.

The pottery of Tell Sabi Abyad is somewhat similar to what was found in the other prehistoric sites in Syria and south-eastern Turkey; for example in Tell Halula, tr:Akarçay Tepe Höyük, de:Mezraa-Teleilat, and Tell Seker al-Aheimar. Yet in Sabi Abyad, the presence of painted pottery is quite unique.[9]

Archaeologists discovered what seems like the oldest painted pottery here. Remarkably, the earliest pottery was of a very high quality, and some of it was already painted. Later, the painted pottery was discontinued, and the quality declined.

Our finds at Tell Sabi Abyad show an initial brief phase in which people experimented with painted pottery. This trend did not continue, however. As far as we can see now, people then gave up painting their pottery for centuries. Instead, people concentrated on the production of undecorated, coarse wares. It was not until around 6200 BC that people began to add painted decorations again. The question of why the Neolithic inhabitants of Tell Sabi Abyad initially stopped painting their pottery is unanswered for the time being.[9]

Pottery found at the site includes Dark Faced Burnished Ware and a Fine Ware that resembled Hassuna Ware and Samarra Ware. Bowls and jars often had angled necks and ornate geometric designs, some featuring horned animals. Only around six percent of the pottery found was produced locally.[10]

Cultural changes around 6200 BC

[edit]

Significant cultural changes are observed at c. 6200 BC, which seem to be connected to the 8.2 kiloyear event. Nevertheless, the settlement was not abandoned at the time.[11]

Important change took place around 6200 BC, involving new types of architecture, including extensive storehouses and small circular buildings (tholoi); the further development of pottery in many complex and often decorated shapes and wares; the introduction of small transverse arrowheads and short-tanged points; the abundant occurrence of clay spindle whorls, suggestive of changes in textile manufacture; and the introduction of seals and sealings as indicators of property and the organization of controlled storage.[1]

Burnt Village

[edit]An unusual "Burnt Village" was discovered here. It was destroyed by a violent fire ca. 6000 BC.

Numerous artefacts were recovered from the burnt buildings; they include pottery and stone vessels, figurines, and all sorts of tools. There were also many storehouses.[1]

A sort of an 'archives' building was found, which contained hundreds of small objects such as ceramics, stone shells and axes, bone implements, and male and female clay figurines. Particularly surprising were the over 150 clay sealings with stamp-seal impressions, as well as the small counting stones (tokens) -- indicating a very early, well-developed registration and administration system.

Clay tokens

[edit]

The site has revealed the largest collection of clay tokens and sealings yet found at any site, with over two hundred and seventy-five, made by a minimum of sixty-one stamp seals.[10] All the sealings were produced with local clay.[12] Such exchange devices were first found in level III of Mureybet during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A and are well known to have developed in the Neolithic.[10][13]

Tell Sabi Abyad I

[edit]

Tell Sabi Abyad I is the largest of the sites (measuring about 240 meters by 170 meters with a height of 10 meters). The mound is actually the result of several smaller mounds merging. It was first occupied between 5200 and 5100 BC during the Neolithic. It showed a later phase of occupation, termed "transitional" by Akkermans, between 5200 and 5100 BC, which was followed by an early Halaf period between 5100 and 5000 BC. Architecture of the 6th-millennium settlement featured multi-room rectangular buildings with round structures called tholoi that were suggested to have been used for storage.[5]

Later remains of a massive structure (23 meters long by 21 meters wide oriented NE-SW) called the "Fortress" were dated to the Middle Assyrian period (Late Bronze Age) between 1550 and 1250 BC.[4] Domestic buildings were also found, suggesting that the settlement was an Assyrian border town where a garrison was stationed.[5] The Fortress structure contained eight rooms with 2.5-metre-wide (8.2 ft) walls constructed of mud bricks and featured a staircase that led to a second floor.[14] The structure was built on top of an existing Mitanni tower and residence.[15]

Cuneiform tablets

[edit]Over 400 cuneiform tablets from the late 13th and twelfth centuries BC have been discovered.

Shortly after 1180 BC, a violent conflagration is attested. Then the attempts were made to partially renovate and reconstruct the buildings. As the cuneiform texts indicate, the Assyrian administrators were still present until the end of the 12th century, although the size of the settlement declined.

Zooarchaeology and archaeobotany

[edit]In the Halaf period, Tell Sabi Abyad had a fully developed farming economy with animal domestication of predominantly goats, but also sheep, cattle and pigs. A small number of gazelle were also hunted, although evidence for hunting and fishing is not well attested at the site.[16]

Trees that would have grown at the time included poplar, willow and ash.[16]

Domesticated emmer wheat was the primary crop grown, along with domesticated einkorn, barley and flax. A low number of peas and lentils were found compared to similar sites.[16]

Tell Sabi Abyad II

[edit]Tell Sabi Abyad II measured 75 metres (246 ft) by 125 metres (410 ft) by 4.5 metres (15 ft) high. Artefacts found evidenced a very early occupation with calibrated dates of around 7550 and 6850 BC.[5][17]

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic B horizon is present; later the site shows an uninterrupted sequence from the pre-pottery to ceramic phase.[9]

2014 destruction

[edit]In 2014, Peter Akkermans revealed that the site and some storage facilities had been plundered as the result of the Syrian Civil War.[18] The site has suffered significant damage from military activity during the Syrian Civil War.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Fieldwork campaign: Tell Sabi Abyad (Syria) universiteitleiden.nl

- ^ Peter M. M. G. Akkermans. “Tell Sabi Abyad: 1986 Campaign.” Syria, vol. 65, no. 3/4, 1988, pp. 399–401

- ^ Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, and Marie le Mière. “The 1988 Excavations at Tell Sabi Abyad, a Later Neolithic Village in Northern Syria.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 96, no. 1, 1992, pp. 1–22

- ^ a b [1] Akkermans, Peter MMG, José Limpens, and Richard H. Spoor. "On the frontier of Assyria: excavations at Tell Sabi Abyad, 1991." (1993)

- ^ a b c d Gosden, 1999, p. 344.

- ^ Akkermans, Peter, et al., "Excavations at late neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria: the 1994-1999 field seasons", Brepols Publishers, 2014 ISBN 978-2-503-53111-3

- ^ Akkermans, Peter M. M. G., et al., "Investigating the Early Pottery Neolithic of Northern Syria: New Evidence from Tell Sabi Abyad", American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 110, no. 1, pp. 123–56, 2006

- ^ [2] Akkermans, Peter & Brüning, Merel, "Architecture and Social Continuity at Neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad III, Syria", 2019

- ^ a b c The very oldest pottery of Tell Sabi Abyad (and of Syria), 7000-6700 BC www.sabi-abyad.nl (archived DEC 14, 2017)

- ^ a b c Maisels, 1999, p. 144.

- ^ J van der Plicht, P G Akkermans, O Nieuwenhuyse, A Kaneda, A Russell, Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria: Radiocarbon Chronology, Cultural Change, and the 8.2 ka Event RADIOCARBON, Vol 53, Nr 2, 2011, p 229–243

- ^ DUISTERMAAT, Kim, and Gerwulf SCHNEIDER. “Chemical Analyses of Sealing Clays and the Use of Administrative Artefacts at Late Neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad (Syria).” Paléorient, vol. 24, no. 1, 1998, pp. 89–106

- ^ Sanner, 1991, p. 29.

- ^ Lipiński, 2000, p. 122.

- ^ [3] Düring, Bleda S., Eva Visser, and Peter MMG Akkermans. "Skeletons in the Fortress: The Late Bronze Age Burials of Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria." Levant 47.1 (2015): 30-50

- ^ a b c Maisels, 1993, p. 136.

- ^ M. Verhoeven, P.M.M.G. Akkermans (eds.), Tell Sabi Abyad II – The Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Settlement - Report on the Excavations of the National Museum of Antiquities Leiden in the Balikh Valley, Syria, (PIHANS vol. 90) VIII, pp. 188, 2000. ISBN 978-90-6258-090-3

- ^ Depots of Leiden archaeologists in Syria plundered archaeology.wiki

- ^ Casana J, Laugier EJ (2017) Satellite imagery-based monitoring of archaeological site damage in the Syrian civil war. PLoS ONE 12(11): e0188589. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188589

Bibliography

[edit]- Akkermans, Peter M. M. G., "A Late Neolithic and Early Halaf Village at Sabi Abyad, Northern Syria", Paléorient, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 23–40, 1987

- Gosden, Chris (1999). The Prehistory of Food: Appetites for Change. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-11765-4.

- Lipiński, Edward (2000). The Aramaeans: Their Ancient History, Culture, Religion. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-0859-8.

- Maisels, Charles (1993). The Near East: Archaeology in the 'Cradle of Civilization'. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-04742-5.

- Maisels, Charles (1999). Early Civilizations of the Old World: The Formative Histories of Egypt, the Levant, Mesopotamia, India and China. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-10975-8.

- Maria Grazia Masetti-Rouault; Olivier Rouault; M. Wafler (2000). La Djéziré et l'Euphrate syriens de la protohistoire à la fin du second millénaire av. J.C, Tendances dans l'interprétation historique des données nouvelles, (Subartu) - Chapter : Old and New Perspectives on the Origins of the Halaf Culture by Peter Akkermans. pp. 43–44.

- Nieuwenhuyse, Olivier P., et al., "Tracing pottery use and the emergence of secondary product exploitation through lipid residue analysis at Late Neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad (Syria)", Journal of Archaeological Science 64, pp. 54–66, 2015

- Rooijakkers, C. Tineke, "Spinning Animal Fibres at Late Neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria?", Paléorient, vol. 38, no. 1/2, pp. 93–109, 2012

- Senner, Wayne M. (1991). The Origins of Writing. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9167-6.

- Verhoeven, Marc, "Traces and Spaces : Microwear Analysis and Spatial Context of Later Neolithic Flint Tools from Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria", Paléorient, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 147–66, 1999