Teriitaria II

| Teriitaria II | |

|---|---|

| Queen regnant of Huahine and Mai’ao Queen and Regent of Tahiti | |

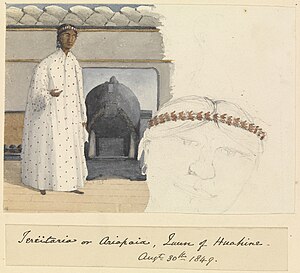

Portrait by Jules-Louis Lejeune, c. 1826 | |

| Queen regnant of Huahine and Mai’ao | |

| Reign | 1815–1852 |

| Predecessor | Mahine Tehei'ura |

| Successor | Ari'imate |

| Born | c. 1790 |

| Died | 1858 (aged 67–68) Papeete, Tahiti |

| Spouse | Pōmare II |

| House | House of Tamatoa |

| Father | Tamatoa III |

| Mother | Tura’iari’i Ehevahine |

| Religion | Tahitian later Protestant |

Teriitaria II or Teri'itari'a II, later known as Pōmare Vahine and Ari'ipaea Vahine, baptized Taaroamaiturai (c. 1790 – 1858), became Queen consort of Tahiti when she married King Pōmare II and later, she ruled as Queen of Huahine and Maiao in the Society Islands.

Teriitaria was the eldest child of King Tamatoa III of Raiatea and Tura’iari’i Ehevahine, a member of the royal family of Huahine. In 1809, Tamatoa arranged for the marriage of Teriitaria and her sister, Teriʻitoʻoterai Teremoemoe, to their widowed second cousin, Pōmare II of Tahiti. Teriitaria became Queen of Huahine in 1815, but did not govern it during the first decades of her rule. In 1815, she fought in the Battle of Te Feipī, which consolidated her husband's rule. Teriitaria had no children with Pōmare II, but Pōmare fathered the next two Tahitian monarchs, Pōmare III (r. 1821–1827) and Pōmare IV (r. 1827–1877), by Teremoemoe. Pōmare II died in 1821, and Teriitaria and Teremoemoe served as regents for Pōmare III and (after his death in 1827) Pōmare IV.

Teriitaria was removed from the regency in 1828, but continued to have an influential role in Tahiti. She led the Tahitian forces in the suppression of the Taiarapu rebellion of 1832. She accompanied her niece, Pōmare IV, into exile on Raiatea during the Franco-Tahitian War (1844–1847). Teriitaria repelled a French invasion force at the Battle of Maeva in 1846, which secured the independence of the Leeward Islands. She was deposed on 26 December 1851 by the governors, the nobility and the people of Huahine and replaced with Ari'imate Teurura'i. She was then banished from the island on 18 March 1854 for troubling the new government. She died in 1858 at Papeete, Tahiti.

Biography

[edit]Birth and family

[edit]In 1768, the islands of Raiatea and Tahaa were conquered by the warrior chief Puni of Faanui on Bora Bora and later ruled by his nephew Tapoa I until the end of the eighteenth-century. While still retaining their esteem because of their chiefly rank, the Tamatoa family, which Teriitaria II belonged to, had lost all secular power and had been displaced for half a century on Raiatea.[1][2][3] Thus, the Tamatoa family resided on Huahine where the chief U'uru had fled during Puni's conquest.[4][5] The Tamatoa line of Raiatea was traditionally considered one of the highest ranking lineages of chiefs. It was connected by marriage and adoption to the hereditary chiefs of the other Society Islands of Tahiti, Moorea, Huahine, Maiao, Tahaa, Bora Bora, and Maupiti. Raiatea and the temple complex of Taputapuatea marae at Opoa were considered the religious center of Eastern Polynesia and the birthplace of the cult of the war deity, 'Oro.[6][7][note 1]

Teriitaria was born around 1790.[9] As the eldest daughter of the family, she held special status since Tahitian society was organised as a matrilineality and therefore traditional titles were passed down by the first-born daughters.[10] Her father was U'uru's son, Tamatoa III, the Ariʻi rahi (King) of Raiatea.[11][note 2] The ariʻi class were the ruling caste of Tahitian society with both secular and religious powers over the common people.[12] Her mother was Tura’iari’i Ehevahine, the daughter of Queen Tehaʻapapa I of Huahine, who was ruling when Captain James Cook visited the Society Islands as part of his first voyage in 1769.[13] Her younger siblings included brother Tamatoa IV and sisters Teriʻitoʻoterai Teremoemoe, Temari'i Ma'ihara, and Teihotu Ta'avea.[14] Teriitaria shared her name with her half-uncle, King Teriʻitaria I, who was ruling Huahine when Cook brought the Tahitian explorer Omai back to the islands from Europe on his third voyage in 1777.[15]

Tahitian names were rooted in land and titles. In the Tahitian language, Teri'i is a contraction of Te Ari'i, meaning the "sovereign" or "chief". The name Teri'itari'a translated literally as "Carried-sovereign". Ari'ipaea (a name she later adopted) means "Sovereign-reserved" or "Sovereign-elect" while Pōmare (a name she later carried, courtesy of her marriage) means "night cougher" with Vahine meaning "woman".[16][17][note 3]

Marriage to Pōmare II

[edit]

During the late 1700s and the early 1800s, Pōmare I had established the Kingdom of Tahiti through the consolidation of traditional titles and the military advantage of Western weapons provided by explorers and traders such as Captain Cook. Protestant missionaries from the London Missionary Society (LMS) settled in Matavai Bay in 1797 under the protection of Pōmare I, although he did not officially convert to the new faith.[24][25] His successor Pōmare II saw this legacy unravel because of internal rivalries between the Pōmare regime and other chiefly families and the fear of foreign influence subverting the traditional Tahitian religion. The district chiefs of Tahiti had revolted, evicted the missionaries and thrown off the rule of the Pōmare family by 1808. Pōmare II and his followers fled into exile to his territorial possessions on the neighbouring island of Moorea after his war party was defeated in December 1808.[26][27]

Pōmare II's union with his first wife Tetua remained childless since both were followers of the Arioi, a religious order that worshipped 'Oro and practiced infanticide. Tetua died following an abortion in 1806.[6][28][29] Around November 1808, Itia, Pōmare II's mother, sought to cement an alliance between the Pōmare dynasty and the established Tamatoa line of Raiatea. The alliance also was strategically important for the exiled king, who needed military assistance to reconquer Tahiti.[6][30] It is said that the ship bearing Teriitaria landed on Moorea a little after the one bearing her younger sister Teriʻitoʻoterai Teremoemoe and that Pomare fell in love with the younger sister. Teriitaria was described as having less feminine features than her fair and elegant younger sister. Unable to reject the older sister for fear of a casus belli (an act to justify war) with Tamatoa III, he married both sisters around 1809.[9][31] In some sources, the marriage is specifically dated to around 8 November 1811.[32][33] Pōmare II preferred her younger sister, but Teriitaria was given the status of queen and the honorary title of Pōmare Vahine.[34][note 4] Pōmare II's grandmother Tetupaia i Hauiri was also a scion of the Raiatea line making him second cousin of his two spouses.[25][36][37]

British missionary John Davies described the circumstances of the marriage and how Teriitaria remained on Huahine and was not brought over to Tahiti and Moorea until 1814–1815.[38][39]

During the absence of the miss. who had gone to the Colony king Pomare had been married to Terito second daughter of Tamatoa chief of Raiatea. His first daughter Teriitaria had been intended for Pomare, and had been in consequence called Pomare Vahine, but their father (much to the disappointment of his eldest daughter) thought proper to marry his second daughter to Pomare, and for this purpose he had her brought up to Tahiti, while the other was left at Huahine.[40]

Teriitaria's marriage with Pōmare II remained childless. Her sister Teremoemoe had three children with him including: Aimata (1813–1877), who ruled as Queen Pōmare IV from 1827 to 1877, Teinaiti (1817–1818), who died young, and Teriitaria (1820–1827), named after his aunt, who reigned as Pōmare III from 1821 to 1827.[41][42][note 5] She was considered the adoptive mother of the young Pōmare III.[44]

Battles for Christianity

[edit]While in exile, Pōmare II began to rely more on the Christian missionaries, including two who had remained—James Hayward and Henry Nott. The rest of the missionaries had fled to New South Wales following the defeat of the Tahitian king in 1808 but were asked to return in 1811 by Pōmare II. The following year, he publicly announced his conversion to Christianity.[45][46] Unlike his father, Pōmare II was not a warrior, and he left the active campaigning to his wives. Teriitaria supported her husband's armies in the reconquest of Tahiti and its eventual Christianization. Described as an Amazon queen, she was an energetic and courageous woman who personally led warriors into battle.[9][47]

In May 1815, Teriitaria and Teremoemoe visited the district of Pare where Teremoemoe‘s daughter Aimata (born 1813) resided with her wet nurse. The native Christians (known as "Bure Atua" or Prayers of God) had re-established themselves in the district. The two women intended to tour Tahiti since it was Teriitaria's first time visiting the island.[48][49][50] However, the Memoirs of Arii Taimai by Henry Adams later claimed they intended to proceed with "their arrangement for the overthrow of the native chiefs".[47] The chiefs of Pare, Hapaiano, and Matavai, who were adherents of the traditional religion, formed an alliance with enemies of Pōmare including the chief of Atehuru and Opuhara, chief of Paparā and a member of the rival Teva clan. They plotted to destroy the royal party and massacre the recent converts. On the night of 7 July, Teriitaria and her party narrowly escaped the plot. They survived largely because either Opuhara or the chief of Atehuru refused to harm women. They fled by night in canoes back to Moorea.[9][48][47][51]

In September 1815, the forces of Pōmare II returned to Pare on Tahiti to assert his paramountcy and reconquer the island from the traditionalists led by Opuhara. Teriitaria was at the head of the Christian warriors alongside Mahine, the king of Huahine and Maiao. The two opposing forces met on the shore in the vicinity of marae Utu'aimahurau (or Nari'i) in the district Pa'ea. The Battle of Te Feipī began on 11 November 1815.[note 6] The fate of the battle was decided when Opuhara was killed in the fighting by Raveae, one of Mahine's men. The Pōmare faction won a decisive victory and restored their rule over Tahiti.[54][55][56][57] British missionary William Ellis, who described the battle as "the most eventful day that had yet occurred in the history of Tahiti", gives a post-facto description of Mahine and Teriitaria preparing for the battle:[note 7]

Mahine, the king of Huahine, and Pomare-vahine, the heroic daughter of the king of Raiatea, with those of their people who had professed Christianity, arranged themselves in battle-array immediately behind the people of Eimeo [Moorea], forming the main body of the army. Mahine on this occasion wore a curious helmet, covered on the outside with plates of the beautifully spotted cowrie, or tiger shell, so abundant in the islands; and ornamented with a plume of the tropic, or man-of-war bird's feathers. The queen's sister, like a daughter of Pallas, tall, and rather masculine in her stature and features, walked and fought by Mahine's side; clothed in a kind of armour, or defence, made with strongly twisted cords of romaha, or native flax, and armed with a musket and a spear. She was supported on one side by Farefau, her steady and courageous friend, who acted as her squire or champion; while Mahine was supported on the other by Patini, a fine, tall, manly chief, a relative of Mahine's family.[58]

The Tahitians abandoned the old religion and converted en masse to Christianity following the battle. The king sanctioned a Tahitian iconoclasm, destroying the traditional foundation of the old religion for any remaining adherents. The marae temples were destroyed, the ti'i figures representing the traditional deities were burned and the construction of new churches commenced. He also sent a collection of his family gods to the London Missionary Society.[57][59][60] Teriitaria and Teremoemoe were already converted to the new faith as well and were numbered among a list of recent converts in December 1814.[61][62] In an 1817 letter to missionary John Eyre in Parramatta, Pōmare II wrote: "There is a great mortality this season. My wife Tarutaria is very ill. Perhaps she will die. The termination of life we know not. None but God knows. With him is life (or salvation.)" She survived the illness.[35]

Pōmare II, who had professed the faith since 1812, was officially baptized on 16 July 1819 in the Royal Mission Chapel at Papaoa, Tahiti. He was the first Tahitian to receive a baptism.[63][64] The remaining members of the royal family were baptized on 10 September 1820 at the Royal Mission Chapel at Papaoa in the presence of a thousand people. Teriitaria, the newborn son of Pōmare II, and Teremoemoe were baptized by missionary William Crook while the elder Teriitaria and Aimata were baptized by Nott. The sisters adopted the names Taaroavahine and Taaroamaiturai, respectively, although they do not seem to have regularly used these names. Despite the ceremony, Pōmare II, Aimata and the elder Teriitaria noticeably did not take part in the Lord’s Supper (Eucharist) because "they did not yet seem decidedly pious".[65][66][67] By 1821, Teriitaria was deemed "more correct in her conducts, and more amiable in her manner" and allowed to take part in the Eucharist.[66] In 1824, the LMS missionaries noted, "She is a member of the church at Papaete [sic], and is considered as a pious woman."[68] However, both sisters were described as "excommunicated members of the church" in 1829 by American missionary Charles Samuel Stewart.[69]

Regent of Tahiti

[edit]

After the death of Pōmare II in 1821, the younger Teriitaria succeeded as King Pōmare III of Tahiti.[9] Being a minor, Pōmare III was placed under a regency council consisting of his aunt Teriitaria, his mother Teremoemoe and the five principal chiefs of Tahiti.[70][71] The council was initially headed by Manaonao (or sometimes Paiti), a chief who took the name Ari'ipaea, with Teriitaria as co-regent. After Manaonao's death in 1823, Teriitaria assumed the head of the regency council.[9][72][73][74] Some argued that Pōmare II intended to choose Tati,[75] brother of the defeated Opuhara and the ruling chief of Paparā, as the regent and guardian for his son. Jacques-Antoine Moerenhout, the French consul in Tahiti, later claimed Pōmare II wanted Tati to succeed him. However, the decision was ignored by the British missionaries because of Tati's independent nature and the fear that he would establish his own dynasty.[76][77] Pōmare III was crowned in a European style coronation ceremony on 21 April 1824 and raised and educated on the island of Moorea by the missionaries.[70][78]

On 6 September 1826, Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones, while in command of the veteran sloop-of-war USS Peacock, signed a treaty with Queen regent Teriitaria and Pōmare III. The treaty established commercial relations between the United States and Tahiti. Thomas Elley, the British vice-consul for the Society Islands, and the resident British missionaries opposed this because the British had no formal treaties with Tahiti. Subsequently, the missionaries discouraged the Tahitian government from entering into treaties with other nations.[79] The regency council remained in power until the death of the young monarch from dysentery in 1827.[80][81][82] She continued ruling as regent for her niece Aimata who reigned as Pōmare IV.[80][69] Her administration was seen as economically oppressive to the Europeans. She sought to monopolize the pearl trade like Pōmare II had attempted with the pork trade, and ignored acts of piracy in the Tuamotus (dependencies of the Tahitian crown). She fixed prices and wages and sent agents to oversee all aspects of foreign trades to the consternation of the Tahitians and foreign merchants. Because of these ineptitudes, she was replaced as regent in April 1828 by Tati.[74] In the 1830s, she took the title and name of Ari'ipaea Vahine.[83][note 8]

Despite her removal from the regency, she continued to hold considerable influence and power and stood second in rank to her niece.[21] In February 1832, Teriitaria along with Tati and other chiefs led the forces of Queen Pōmare IV and suppressed a rebellion in Taiarapu (modern-day Taiarapu-Est and Taiarapu-Ouest) led by a local chief named Ta'aviri. The rebellion was supported by the Mamaia heresy, a millenarian movement which synchronized Christianity with traditional indigenous beliefs. The Mamaia movement prophesied a victory for the rebel forces. Teriitaria personally commanded her warriors with a sabre and pistol in her hand. The battle on 12 February resulted in a decisive defeat for the rebel forces and the eventual suppression of the Mamaia heresy.[9][89]

Ruler of Huahine

[edit]

In 1815, Teriitaria became the nominal Queen of Huahine and Maiao. The previous ruler, Mahine, fought alongside her at the Battle of Te Feipī. Ellis stated that by the 1820s, Mahine had formally presented the government of the islands to her while he remained the resident chief until his death in 1838.[90][91] She ruled largely as an absentee monarch while residing on Tahiti for the first few decades of her reign.[9] Her later reign coincided with the Franco-Tahitian War.[92] Pōmare IV was deposed in 1843 by French naval commander Abel Aubert du Petit-Thouars in an attempt to annex Tahiti. From 1844 to 1847, Teriitaria accompanied her niece into voluntary exile on Raiatea as a protest against the seizure of the Tahitian throne by the French.[9][93]

In 1845 she defeated an attempt by the French to establish a protectorate over the remaining independent states of the Leeward Islands (Bora Bora, Raiatea and Huahine). With the support of two local chiefs named Haperoa and Teraimano, the French planted a French flag on Huahine soil and threatened to retaliate against anyone who tried to remove it. While on Raiatea, Teriitaria learned of the actions of her subordinate and rallied a force of Raiatean warriors and sailed for Huahine in a whaler. She assembled the people and had them chop the flagstaff down. She then pulled it out herself before sending the flag back to Armand Joseph Bruat, the French governor of Tahiti.[9][94]

A renewed effort to conquer Huahine was made when Commandant Louis Adolphe Bonard was ordered to go to the island and make a show of force. On 17 January 1846, he landed 400 soldiers and marines at Fare harbour. During the Battle of Maeva, Territaria’s forces, supported by around 20 Europeans, held the French off for two days, killing 18 and wounding 43, before they abandoned the attempt and sailed away.[95][96] Edward Lucett, a British merchant and an island shipowner, noted, "Old Ariipae, musket in hand, and with half a dozen cartouch [sic] boxes belted round her slender waist, was there to encourage her people".[22] This decisive defeat lifted the French naval blockade of Raiatea and forced them to evacuate Bora Bora effectively liberating the Leeward Islands. The French returned to suppress the guerrilla war still waging on Tahiti.[97][98][99]

Although Great Britain never intervened militarily, the British naval officer Henry Byam Martin and commander of HMS Grampus, was sent to the Society Islands to spy on the conflict. His account of the closing months of the conflict are recorded in The Polynesian Journal of Captain Henry Byam Martin, R.N. Marin had an audience with the aged warrior queen at Fare on 21 April 1847 where she told him that, "I would resist the French flag to the last." Below is an excerpt of Martin's impression of the queen:[100][101]

I landed at the dwelling of Ariipuia the Queen – for a roof resting on posts without any walls can hardly be called a house. Of this lady I had heard much – as being the most perfect type of an Amazon in the known world. Many good stories are told of her in the island wars – in which she always headed her people – and when their courage flagged – she seized a musket – denounced them as cowards, and by her own prowess & personal example retrieved the day. Ariipuia is certainly no beauty – a tough leathery old woman with a sharp quick eye and a certain look of the devil that fits her character very well. She is said to be every inch a griffon – and by Jove she looks it. She seems about 60 yrs old, but she has not yet renounced the foibles of her sex.[102]

Attempts to conquer the neighbouring kingdoms of the Leeward Islands ceased after the French withdrew their troops, but guerilla warfare continued between the French and Tahitians on Tahiti until 1846 when Fort Fautaua, the native stronghold, was captured by the French. In February 1847, Queen Pōmare IV returned from her exile and acquiesced to rule under the protectorate. Although victorious, the French were unable to annex the islands due to diplomatic pressure from Great Britain, so Tahiti and its dependency Moorea continued to be ruled under the French protectorate. The Jarnac Convention was also signed by France and Great Britain, in which the two powers agreed to respect the independence of Huahine, Raiatea, and Bora Bora.[92][103][104]

Not trusting the French would not seek reprisal for their defeat on Huahine, Teriitaria refused to return to Papeete with her niece in 1847.[9] She wrote a letter to Queen Victoria, dated 3 February 1847, asking her to protect the independence of the Leeward Islands.[105][106] The traditional alliance of the chiefly families of the Society Islands have been termed the hau pahu rahi ("government of the great drum") or hau feti'i (“family government"). This alliance was severely tested when the French attempted to characterize it as evidence of Queen Pōmare IV's dominion over the rest of the islands.[7] As a gesture to the enduring nature of the hau feti'i, Teriitaria adopted Queen Pōmare IV's second son Terātane as her heir to the throne of Huahine and named him Teriitaria. Instead of becoming the next king of Huahine, this boy would one day succeeded his mother as King Pōmare V.[107][108][109] She was also the adoptive mother Ninito Teraʻiapo Sumner (died 1898), one of the granddaughters of Tati. Betrothed to Prince Moses Kekūāiwa, she arrived in Hawaii after his death from measles in 1848 and later married into the prominent Sumner family on Hawaii.[110]

Deposition

[edit]

Between 1851 and 1854, she lost control over her rule of Huahine. The succession becomes confusing at this point in history, and historians have found the exact details of the transition of power hard to piece together.[20][111]

In 1850, Teriitaria's followers destroyed the cargo and plantation of European trader John Brander for refusing to pay port dues. A commission of French, American, and British officials forced the queen to pay a restitution of $287, which were collected from all the districts of Huahine.[112] Teriitaria was deposed on 26 December 1851 by the governors, nobility and common people of Huahine. In a letter written to the British consul, the people of Huahine cites the reasons for her deposition included her seizure of land, punishment of people without any regards to her own laws, and the oppression of foreigners.[113] Mahine's grandson Ari'imate Teurura'i (1824–1874) was chosen as the new king on January 5, 1852 to replace the deposed queen.[114]

A civil war broke out in 1852 on Huahine.[115] Reports of the political upheaval were written down in detail by the LMS missionary Charles Barff. Between June and September, a rebellion was staged by Otave, the king's advisor. Otave had been instrumental in deposing Teriitaria in favor of Teurura'i but now sought to elevate himself as king under the new name Kianmarama (the reign of the moon). The rebellion was briefly quelled by Teurura'i in a battle on 29 September where two rebels died, and many were exiled to Raiatea or Tahiti. Paoua, one of the rebels exiled to Tahiti, returned on 31 October and feigned submission to Teururai. However, he secretly messaged the rebels on Raiatea to row back to Huahine in the middle of the night thus restarting the rebellion. The rebels attacked Teururai on 18 December and fighting continued until 7 January 1853 when the two parties agreed to negotiate a peaceful settlement to the conflict. The rebels requested that Teriitaria's adopted son be installed as the new monarch of Huahine and Teurura'i and his supporters agreed as well. A treaty dated 11 January 1853 was drafted and signed by both parties and sent to the French governors and British consuls on Tahiti. Teriitaria and her adopted son were recalled on 15 June and returned to the island on a French steamer. Despite repeated promises by all islanders to abide by the treaty, hostilities recommenced with Teriitaria "continu[ing] to make unceasing threats of attack on Teururai". The supporters of Teriitaria were the first to attack the settlement of Teururai. Despite superior numbers, Teriitaria and her supporters were defeated after a violent battle on 18 March 1854.[116][117] Nine "Teriitarians" were killed and ten were wounded while Teururai's forces only suffered six injuries. On the following day, Paoua was sent by Teriitaria to surrender and give up their weapons and gunpowder. On 26 March, the French steamer took away the defeated parties to Tahiti including the twice deposed queen and her adopted son as "prisoners of war".[116]

Writing between 1852 and 1860, French naval physician Gilbert Henri Cuzent noted: "Terii-Taria, vieille reine de Huahine qui, restée sans postérité, a été détrônée il n'y a pas encore longtemps pour faire place à un de ses neveux." or "Terii-Taria, old queen of Huahine who, left without posterity, was dethroned not long ago to make room for one of her nephews."[20] Ari'imate was her nephew by marriage, having married her paternal niece who later reigned in her own right as Tehaʻapapa II in 1868.[118][119][120]

In the Histoire de Huahine et autres îles Sous-le-Vent written by Father Joseph Chesneau from 1907 to 1914 in collaboration with Pascal Marcantoni, an alternative history of Huahine is given. Teriitaria's reign ends before the Franco-Tahitian War and her immediate successor is named Queen Teuhe I (wife of Mahine's son Taaroarii),[note 9] and Chesneau names her as the queen who fought the French at Maeva. According to this alternative historical account, Teuhe I was followed by Ma'ihara Temari'i (1822–1877), who also reigned under the name of Teriitaria (adding more confusion) and this Teriitaria was deposed by her brother Ari'imate on 18 March 1854.[121][118]

According to resident British missionary John Barff, Teriitaria's[note 10] deposition was rooted in the erosion of the traditional power of the ariʻi class and the civil unrest of the ra'atira class of freemen. They objected to "the encroachment of the supreme chiefs upon the powers of the district governors and the insecurity to property resulting from the continuance of the old practice in which the chiefs indulged of taking food from the plantation of their subjects whenever they chose to".[123]

Teriitaria died at Papeete in 1858, at the royal palace in the presence of her sister and her niece.[9][124]

Family tree

[edit]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes:

The numbering of the Tamatoa varies. An ancestor of the Tamatoa line named Fa'aniti is often counted as "Tamatoa I" and Moeore is sometime not considered Tamatoa IV.[125]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes:

Descending dotted lines denote adoptions.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes:

Descending dotted lines denote adoptions.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Society Islands are subdivided into the Windward Islands or Georgian Islands (in the southeast) and the Leeward Islands (in the northwest).[8]

- ^ He is sometimes referred to as Tamatoa II or Tamatoa IV depending on the sources.

- ^ There is no set spelling for the names of most Tahitian historical figures, nor is there any consensus on when to use the ʻeta (the Tahitian glottal stop); variations of her name include: Teriitaria, Teri'itaria, Teri'itari'a, Teari'itaria, Terii-Taria, Arepaea, Ariipae, Ariipuia, Ari'ipaea, Ariapaea, and variations of Pōmare Vahine.[18][19][20][21][22] One source confuses her with her sister Teriʻitoʻoterai Teremoemoe and calls her Teritoiterai.[23] For ease of understanding, she will be referred to as Teriitaria throughout the article.

- ^ One source refers to Teriitaria as a concubine.[9] Some sources do not mention her status as his wife (Ellis 1834; Newbury 1980; Adams 1901). The British missionaries recognized her sister as queen and referred to her as the queen's sister.[33] Although, in an 1817 letter, Pōmare II referred to her as "My wife Tarutaria".[35]

- ^ Early sources incorrectly state Aimata was Teriitaria's daughter.[43]

- ^ Te Feipī translates as "the Ripe Plantain" in Tahitian.[52] The British missionaries recorded that the Battle of Te Feipī occurred on the Sabbath on 12 November 1815. However, the local Tahitian calendar was one day ahead of the rest of the world and would not be corrected until 1848.[53]

- ^ None of the missionaries witnessed the battle and the earliest written accounts were not recorded until March 1816 in the letters of John Davies. In the 1820s, Ellis relied on a Tahitian informant named Auna to help him piece together the details of the battle.[54]

- ^ Ari'ipaea was also the name and title of many other Tahitian royal figures including the aforementioned Manaonao or Paiti, the half-brother and sister/aunt of Pōmare I.[84][85][86][87][88]

- ^ Not to be confused with her granddaughter Teuhe, who is sometimes called Teuhe II.[119]

- ^ It is uncertain if this refers to the elderly Teriitaria II or Ma'ihara Temari'i. Historian Colin Newbury adds more confusion by referring to the deposed Queen of Huahine in 1852 as a sister of Tamatoa V.[122]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Newbury 1980, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Newbury & Darling 1967, pp. 492–495.

- ^ Newbury 2009, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Newbury & Darling 1967, p. 493.

- ^ Pōmare II 1812, pp. 281–282.

- ^ a b c Dodd 1983, p. 69.

- ^ a b Newbury & Darling 1967, pp. 477–514.

- ^ Perkins 1854, pp. 439–446.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Teissier 1978, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Gunson 1964, p. 64.

- ^ Newbury & Darling 1967, pp. 493–494; Cuzent 1872, p. 4; Baré 1987, pp. 6, 83; Perkins 1854, p. 238

- ^ Newbury & Darling 1967, pp. 477–481.

- ^ Baré 1979, p. 6.

- ^ Henry & Orsmond 1928, pp. 252–253, 257; Teissier 1978, pp. 72–76; Cadousteau 1987, p. 49

- ^ Henry & Orsmond 1928, pp. 252, 257; Newbury & Darling 1967, pp. 493–494; Salmond 2009, p. 282; Beaglehole & Cook 2017, pp. 232–233

- ^ Henry & Orsmond 1928, pp. 220, 252.

- ^ Stevenson 2014, p. 142.

- ^ Davies 1961, p. 390.

- ^ Martin 1981, p. 191.

- ^ a b c Cuzent 1860, p. 45.

- ^ a b Wilkes 1845, p. 18.

- ^ a b Lucett 1851, p. 145.

- ^ Loud 1899, pp. 116, 120–123.

- ^ Newbury 1980, pp. 14–30.

- ^ a b Teissier 1978, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Newbury 1980, pp. 27–30.

- ^ Adams 1901, pp. 148–157.

- ^ Teissier 1978, pp. 51.

- ^ Ellis 1834, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Davies 1961, pp. 126, 153.

- ^ Ellis 1834, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Adams 1901, pp. 154–155.

- ^ a b Gunson 2016, p. 330.

- ^ Moerenhout & Borden 1993, pp. 514–515, 528; Adams 1901, pp. 154–155; Mortimer 1838, pp. 226–227; Calderon 1922, pp. 209–210; Dodd 1983, p. 69; Davies 1961, pp. 126, 153

- ^ a b Pōmare II 1817, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Orsmond & Smith 1893, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Henry & Orsmond 1928, pp. 247–252.

- ^ Davies 1961, pp. 137–138, 153.

- ^ Ellis 1831b, p. 10.

- ^ Davies 1961, p. 153.

- ^ Teissier 1978, pp. 50–54.

- ^ Henry & Orsmond 1928, p. 249.

- ^ Smith 1825, p. 86.

- ^ Tyerman & Bennet 1832b, p. 218.

- ^ Newbury 1980, pp. 33–44.

- ^ Ellis 1834, pp. 88–89, 93–96.

- ^ a b c Adams 1901, p. 157.

- ^ a b Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1816, pp. 406–407.

- ^ Newbury 1980, p. 37.

- ^ Davies 1961, p. 188.

- ^ Ellis 1834, pp. 134–142.

- ^ Adams 1901, p. 158.

- ^ Newbury 1980, pp. 37, 124.

- ^ a b Newbury 1980, pp. 37–39.

- ^ Ellis 1834, pp. 145–151.

- ^ Adams 1901, pp. 148–160.

- ^ a b Gleizal, Christian. "1815 – La bataille de Fei Pi". Histoire de l'Assemblée de la Polynésie française. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Ellis 1834, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Newbury 1980, p. 38.

- ^ Sissons 2014, pp. 29–61.

- ^ Davies 1961, p. 185.

- ^ Newbury 1980, pp. 34.

- ^ Ellis 1834, pp. 93–96.

- ^ Garrett 1982, pp. 21–24.

- ^ Crook 1822, pp. 148–149.

- ^ a b Mortimer 1838, p. 328.

- ^ Tyerman & Bennet 1832a, pp. 99, 142.

- ^ Smith 1825, p. 91.

- ^ a b Stewart 1832, pp. 262–263.

- ^ a b O'Reilly & Teissier 1962, pp. 366–367.

- ^ Tyerman & Bennet 1832a, p. 144.

- ^ Lescure 1948, p. 422.

- ^ Newbury 1980, pp. 49–50, 56.

- ^ a b Gleizal, Christian. "La régence". Histoire de l'Assemblée de la Polynésie française. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Teissier 1978, pp. 81–86.

- ^ Tyerman & Bennet 1832a, pp. 111, 144.

- ^ Adams 1901, p. 176.

- ^ Tyerman & Bennet 1832b, pp. 218–222.

- ^ O'Reilly & Teissier 1962, pp. 366–367; Newbury 1980, p. 70; Pritchard 1983, p. 53; Smith 2000, pp. 56–59; Bolton 1937, pp. 45–46

- ^ a b Calderon 1922, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Kirk 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Stevenson & Rousseau 1982, p. 20.

- ^ Davies 1961, p. 126.

- ^ Salmond 2009, p. 282.

- ^ Adams 1901, p. 111.

- ^ Teissier 1978, p. 47.

- ^ Bligh & Oliver 1988, p. 109.

- ^ Newbury 1980, pp. 18, 26, 50.

- ^ Gunson 1962, pp. 208–243.

- ^ Ellis 1831a, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Ellis 1834, pp. 346, 389.

- ^ a b Matsuda 2005, pp. 91–112.

- ^ Pritchard 1878, p. 60.

- ^ Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1845, pp. 585–586.

- ^ Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1846, pp. 585–586.

- ^ Newbury 1973, pp. 13–14; Matsuda 2005, pp. 97, 101–102; McArthur 1967, p. 267; Kirk 2012, p. 153; Layton 2015, p. 177

- ^ Matsuda 2005, pp. 97, 101–102.

- ^ Newbury 1980, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Martin 1981, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Martin 1981, pp. 7–11.

- ^ Martin 1981, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Martin 1981, p. 132.

- ^ Olson & Shadle 1991, p. 329.

- ^ Gonschor 2008, pp. 32–39, 42–51.

- ^ Baré 1987, p. 557.

- ^ Gonschor 2008, p. 45.

- ^ Newbury 1967, p. 18.

- ^ Martin 1981, pp. 133.

- ^ Teissier 1978, pp. 42–44.

- ^ Henry & Orsmond 1928, pp. 220, 270–271.

- ^ Newbury 1967, p. 20; Newbury 1980, pp. 190–191; Christian 1989, p. 30

- ^ Newbury 1956, pp. 396–398.

- ^ "Consuls for Society and Navigator Islands: Miller, Nicolas, Pritchard".

- ^ "Consuls for Society and Navigator Islands: Miller, Nicolas, Pritchard".

- ^ McArthur 1967, p. 267.

- ^ a b "Missionary In℡Ligence". Launceston Examiner. 25 July 1854.

- ^ "Nouvelles Diverses". Messager de Tahiti. Vol. I, no. 13. Papeete. 26 March 1854. p. 3. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ a b Teissier 1978, pp. 59, 110–113.

- ^ a b Chesneau 1928, pp. 88–90.

- ^ Henry & Orsmond 1928, pp. 253–255.

- ^ Chesneau 1928, pp. 81–88.

- ^ Newbury 1967, pp. 18, 20.

- ^ Newbury 1967, p. 20.

- ^ Cuzent 1872, p. 6.

- ^ Henry & Orsmond 1928, p. 248.

Sources

[edit]- Adams, Henry (1901). Tahiti: Memoirs of Arii Taimai. Ridgewood, NJ: The Gregg Press. OCLC 21482.

- Baré, Jean-François (1979). Huahine. Dossiers Tahitiens (in French). Vol. 26. Translated by Colin W. Newbury. Paris: Nouvelles Editions Latines. ISBN 9782723300773. OCLC 760977322. GGKEY:LEP1CU9W5JS.

- Baré, Jean-François (1987). Tahiti, les temps et les pouvoirs: pour une anthropologie historique du Tahiti post-européen (in French). Paris: ORSTOM, Institut français de recherche scientifique pour le développement en coopération. ISBN 978-2-7099-0847-4. OCLC 16654716.

- Beaglehole, J. C.; Cook, James (2017). The Journals of Captain James Cook on his Voyages of Discovery: Volume III, Part I: The Voyage of the Resolution and Discovery 1776–1780. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-54322-4.

- Bligh, William; Oliver, Douglas L. (1988). Return to Tahiti: Bligh's Second Breadfruit Voyage. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1184-6. OCLC 153702166.

- Bolton, W. W. (23 July 1937). "The Boy-King of Tahiti and His Treaty". Pacific Islands Monthly. Vol. VII, no. 12. Sydney: Pacific Publications. pp. 45–46. OCLC 780465500.

- Cadousteau, Mai-Arii (1987). "CHAPITRE VIII: AHU'URA FILLE DU ROI MAI III". Généalogies Commentées des Arii des Îles de la Société (in French). Papeete: Société des Études Océaniennes. pp. 45–50. OCLC 9510786.

- Calderon, George (1922). Tahiti by Tihoti. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. OCLC 757277273.

- Christian, Erwin (1989). Bora Bora. Edison, NJ: Hunter Publishing, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-55650-198-2. OCLC 21321148.

- Chesneau, Joseph (August 1928). "Notes sur Huahine et autres Iles-Sous-le-Vent". Bulletin de la Société des Études Océaniennes (in French) (26). Papeete: Société des Études Océaniennes: 81–98. OCLC 9510786. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Crook, William (January 1822). "Extracts from the Journal of Mr. Crook, Mount Hope, Taheite, 1820". The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle. London: Williams and Son. pp. 148–149. OCLC 682032291.

- Cuzent, Gilbert (1860). Îles de la société Tahiti: considérations géologiques, météorologiques et botaniques sur l'île. État moral actuel des Tahitiens, traits caractéristiques de leurs moeurs, végétaux susceptibles de donner des produits utiles au commerce et a l'industrie, et de procurer des frets de retour aux navires, cultures et productions horticoles, catalogue de la flore de Tahiti, dictionnaire Tahitien (in French). Rochefort: Impr. Thèze. OCLC 13494527. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Cuzent, Gilbert (1872). Voyage aux îles Gambier (Archipel de Mangarèva) (in French). Paris: V. Masson et Fils. OCLC 41189850.

- Davies, John (2017) [1961]. Newbury, Colin W. (ed.). The History of the Tahitian Mission, 1799–1830, Written by John Davies, Missionary to the South Sea Islands: With Supplementary Papers of the Missionaries. London: The Hakluyt Society. doi:10.4324/9781315557137. ISBN 978-1-317-02871-0. OCLC 992401577.

- Dodd, Edward (1983). The Rape of Tahiti. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. ISBN 978-0-396-08114-2. OCLC 8954158. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Ellis, William (1834). Polynesian Researches, During a Residence of Nearly Eight Years in the Society and Sandwich Islands. Vol. II (2nd ed.). London: Fisher, Son, & Jackson. OCLC 1061902349.

- Ellis, William (1831). Polynesian Researches, During a Residence of Nearly Eight Years in The Society and Sandwich Islands. Vol. III (2nd ed.). London: Fisher, Son & Jackson. OCLC 221587368.

- Ellis, William (1831). A Vindication of the South Sea Missions from the Misrepresentations of Otto Von Kotzebue, Captain in the Russian Navy: With an Appendix. London: F. Westley and A.H. Davis. OCLC 14184834.

- Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle (October 1816). "South Sea Mission". The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle. London: Williams and Son. pp. 405–409. OCLC 682032291.

- Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle (December 1845). "The French at Huahine". The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle. Vol. XXIII (New ed.). London: Thomas Ward and Co. pp. 585–586. OCLC 682032291.

- Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle (August 1846). "Destruction of the Town of Fare by the French". The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle. Cambridge: Andover-Harvard Theological Library. pp. 437–438.

- Garrett, John (1982). To Live Among the Stars: Christian Origins in Oceania. Suva, Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific. ISBN 978-2-8254-0692-2. OCLC 17485209. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Gonschor, Lorenz Rudolf (August 2008). Law as a Tool of Oppression and Liberation: Institutional Histories and Perspectives on Political Independence in Hawaiʻi, Tahiti Nui/French Polynesia and Rapa Nui (PDF) (MA thesis). Honolulu: University of Hawaii at Manoa. hdl:10125/20375. OCLC 798846333. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Gunson, Niel (June 1962). "An Account of the Mamaia or Visionary Heresy of Tahiti, 1826–1841". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 71 (2). Wellington: The Polynesian Society: 209–243. JSTOR 20703998. OCLC 5544737364. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Gunson, Niel (March 1964). "Great Women and Friendship Contract Rites in Pre-Christian Tahiti". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 73 (1). Wellington: The Polynesian Society: 53–69. JSTOR 20704150. OCLC 5544738069. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Gunson, Niel (July 2016). "Manuscript XXX: The Letters of Pā". The Journal of Pacific History. 51 (3). Canberra: Australian National University: 330–342. doi:10.1080/00223344.2016.1230076. OCLC 6835510203. S2CID 163709722.

- Henry, Teuira; Orsmond, John Muggridge (1928). Ancient Tahiti. Vol. 48. Honolulu: Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum. OCLC 3049679. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Kirk, Robert W. (2012). Paradise Past: The Transformation of the South Pacific, 1520–1920. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7864-9298-5. OCLC 1021200953.

- Layton, Monique (2015). The New Arcadia: Tahiti's Cursed Myth. Victoria, BC: FriesenPress. ISBN 978-1-4602-6860-5. OCLC 930600657. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Lescure, Rey (1948). "Documents pour l'histoire de Tahiti". Bulletin de la Société des Études Océaniennes (in French) (82). Papeete: Société des Études Océaniennes. OCLC 9510786. Archived from the original on 20 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Loud, Emily Syrena (1899). Taurua: Or, Written in the Book of Fate. Cincinnati: Editor Publishing Company. OCLC 1029662317.

- Lucett, Edward (1851). Rovings in the Pacific, from 1837 to 1849: With a Glance at California. Vol. 2. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. OCLC 6786628. Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- Martin, Henry Byam (1981). The Polynesian Journal of Captain Henry Byam Martin, R. N. (PDF). Canberra: Australian National University Press. hdl:1885/114833. ISBN 978-0-7081-1609-8. OCLC 8329030. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Matsuda, Matt K. (2005). "Society Islands: Tahitian Archives". Empire of Love: Histories of France and the Pacific. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 91–112. ISBN 978-0-19-534747-0. OCLC 191036857. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- McArthur, Norma (1967). Island Populations of the Pacific (PDF). Canberra: Australian National University Press. OCLC 1647169. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Moerenhout, Jacques Antoine (1837). Voyages aux îles du Grand Océan (in French). Paris: Arthur Bertrand. OCLC 962425535.

- Moerenhout, Jacques Antoine; Borden, Arthur R. (1993). Travels to the Islands of the Pacific Ocean. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-8191-8898-4. OCLC 26503299.

- Mortimer, Favell Lee (1838). The Night of Toil; Or a Familiar Account of the Labours of the First Missionaries in the South Sea islands: By the Author of the 'Peep of Day'. London: J. Hatchard and Son. OCLC 752899081.

- Newbury, Colin W. (1956). The Administration of French Oceania, 1842–1906 (PDF) (PhD thesis). Canberra: A Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Australian National University. hdl:1885/9609. OCLC 490766020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- Newbury, Colin W. (March 1967). "Aspects of Cultural Change in French Polynesia: The Decline of the Ari'i". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 76 (1). Wellington: The Polynesian Society: 7–26. JSTOR 20704439. OCLC 6015277685. Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Newbury, Colin W. (September 2009). "Pacts, Alliances and Patronage: Modes of Influence and Power in the Pacific". The Journal of Pacific History. 44 (2). Canberra: Australian National University: 141–162. doi:10.1080/00223340903142108. JSTOR 40346712. OCLC 4648099874. S2CID 142362747.

- Newbury, Colin W. (March 1973). "Resistance and Collaboration in French Polynesia: the Tahitian War: 1844–7". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 82 (1). Wellington: The Polynesian Society: 5–27. JSTOR 20704899. OCLC 5544738080. Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Newbury, Colin W. (1980). Tahiti Nui: Change and Survival in French Polynesia, 1767–1945 (PDF). Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii. hdl:10125/62908. ISBN 978-0-8248-8032-3. OCLC 1053883377. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Newbury, Colin W.; Darling, Adam J. (December 1967). "Te Hau Pahu Rahi: Pomare II and the Concept of Interisland Government in Eastern Polynesia". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 76 (4). Wellington: The Polynesian Society: 477–514. JSTOR 20704508. OCLC 6015244633. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Olson, James Stuart; Shadle, Robert (1991). Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism. New York: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-26257-9. OCLC 21950673. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- O'Reilly, Patrick; Teissier, Raoul (1962). Tahitiens: répertoire bio-bibliographique de la Polynésie française (in French) (1st ed.). Paris: Musée de l'homme. OCLC 1001078211.

- Orsmond, John Muggridge; Smith, S. Percy (March 1893). "The Genealogy of the Pomare Family of Tahiti, from the Papers of the Rev. J. M. Orsmond. With Notes Thereon by S. Percy Smith". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 2 (1). Wellington: The Polynesian Society: 25–43. JSTOR 20701269. OCLC 5544732839. Archived from the original on 18 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Perkins, Edward T. (1854). Na Motu, or, Reef-Rovings in the South Seas: a Narrative of Adventures at the Hawaiian, Georgian and Society Islands. New York: Pudney & Russell. ISBN 9785870949536. OCLC 947055236.

- Pōmare II (July 1812). "Translation of a Letter from Pomarre, King of Otaheite, to the Rev. W. Henry, one of the Missionaries who had long resided on that Island, and who has, with several others, lately returned to it". The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle. London: Williams and Son. pp. 281–282. OCLC 682032291.

- Pōmare II (1819). "Translation Of A Letter From Pomare, King of Otaheite, &c. To Mr. John Eyre, At Paramatta". The American Baptist Magazine, and Missionary Intelligencer. Vol. 2. Boston: James Loring, and Lincoln & Edmands. pp. 69–70. OCLC 1047669001.

- Pritchard, George (1983). The Aggressions of the French at Tahiti: And Other Islands in the Pacific. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-647994-1. OCLC 10470657.

- Pritchard, George (1878). Queen Pomare and Her Country. London: Elliot Stock. OCLC 663667911. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Salmond, Anne (2009). Aphrodite's Island: The European Discovery of Tahiti. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26114-3. OCLC 317461764.

- Sissons, Jeffrey (2014). The Polynesian Iconoclasm: Religious Revolution and the Seasonality of Power. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78238-414-4. JSTOR j.ctt9qcvw9. OCLC 885451227.

- Smith, Thomas (1825). The History and Origin of the Missionary Societies, Etc. (Appendix.). London. OCLC 1063996422.

- Smith, Gene A. (2000). Thomas Ap Catesby Jones: Commodore of Manifest Destiny. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-848-5. OCLC 247899223.

- Stevenson, Karen; Rousseau, Cécile (1982). Artifacts of the Pomare Family. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Commons Gallery, Punaauia : Le musée de Tahiti et des îles, 1981. OCLC 490711845.

- Stevenson, Karen (June 2014). "ʻAimata, Queen Pomare IV: Thwarting Adversity in Early 19th Century Tahiti". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 123 (2). Wellington: The Polynesian Society: 129–144. doi:10.15286/jps.123.2.129-144. JSTOR 43286236. OCLC 906004458.[permanent dead link]

- Stewart, Charles Samuel (1832). A Visit to the South Seas, in the U.S. Ship Vincennes, During the Years 1829 and 1830: With Notices of Brazil, Peru, Manilla, the Cape of Good Hope, and St. Helena. Vol. 1. London: Fisher, Son, & Jackson. OCLC 1021222101. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Teissier, Raoul (1978). "Chefs et notables des Établissements Français de l'Océanie au temps du protectorat: 1842–1850". Bulletin de la Société des Études Océaniennes (in French) (202). Papeete: Société des Études Océaniennes. OCLC 9510786. Archived from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Tyerman, Daniel; Bennet, George (1832). Journal of Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq: Deputed from the London Missionary Society, to Visit Their Various Stations in the South Sea Islands, China, India, &c. Between the Years 1821 and 1829. Vol. 1. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. OCLC 847088.

- Tyerman, Daniel; Bennet, George (1832). Journal of Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq: Deputed from the London Missionary Society, to Visit Their Various Stations in the South Sea Islands, China, India, &c. Between the Years 1821 and 1829. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. OCLC 254679265.

- Wilkes, Charles (1845). Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition: During the Years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. Vol. II. London: Lea and Blanchard. OCLC 1335141.

Further reading

[edit]- Saura, Bruno (2015). Histoire et mémoire des temps coloniaux en Polynésie françasie (in French). Papeete: Au vent des îles. ISBN 978-2-36734-178-1. OCLC 933526850.

- Saura, Bruno (2005). Huahine Aux Temps Anciens (in French). Papeete: Ministère de la culture de Polynésie française. ISBN 978-2-912409-02-7. OCLC 493919438.