The Ipcress File (film)

| The Ipcress File | |

|---|---|

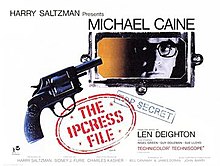

Original British 1965 quad film poster | |

| Directed by | Sidney J. Furie |

| Screenplay by | Bill Canaway James Doran |

| Produced by | Harry Saltzman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Otto Heller |

| Edited by | Peter R. Hunt |

| Music by | John Barry |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Rank Organisation (UK) Universal Pictures (US) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $3,000,000 (US/Canada rentals)[2] |

The Ipcress File is a 1965 British espionage film directed by Sidney J. Furie, starring Michael Caine and featuring Guy Doleman and Nigel Green. The screenplay by Bill Canaway and James Doran was based on Len Deighton's novel, The IPCRESS File (1962). It has won critical acclaim and a BAFTA award for best British film. In 1999 it was included at number 59 on the BFI list of the 100 best British films of the 20th century.

Plot

A scientist called Radcliffe is kidnapped and his security escort killed. Harry Palmer, a British Army sergeant with a criminal past now working for a Ministry of Defence organisation, is summoned by his boss, Colonel Ross, and transferred to a section of the organisation headed by Major Dalby.

Ross suspects that Radcliffe's disappearance is connected to a plot: sixteen top British scientists have inexplicably left their jobs at the peak of their careers. He threatens Dalby that his group will go if Radcliffe cannot be recovered. Palmer is then introduced as a replacement for the dead security escort.

At his first departmental meeting, Palmer befriends Jock Carswell. Dalby briefs his agents, saying that they suspect Eric Grantby and his chief of staff, codenamed "Housemartin". Using a Scotland Yard contact, Palmer locates Grantby, who gives him a phone number, but it does not work. When Palmer tries to stop Grantby, Housemartin attacks him and the two get away.

Housemartin is arrested, but before Palmer and Carswell can question him, he is killed by men impersonating them. Suspecting that Radcliffe is being held in a certain disused factory, Palmer orders a search, but nothing is found except a piece of audiotape marked "IPCRESS" that produces a meaningless noise when played.

Dalby then points out that the paper on which Grantby wrote the phone number is the programme for an upcoming military band concert. There they encounter Grantby and a deal is struck for Radcliffe's return. The exchange goes as planned, but as they are leaving, Palmer sees a man in the shadows and shoots him. It turns out to be a CIA agent who has also been following Grantby. Subsequently, another CIA operative threatens to kill Palmer if he discovers that the death was not a mistake.

Some days later, it becomes clear that while Radcliffe is physically unharmed, his mind has been affected and he can no longer function as a scientist. Carswell discovers a book titled "Induction of Psychoneuroses by Conditioned Reflex under Stress": IPCRESS, which he believes explains what has happened to Radcliffe and the other scientists. Carswell borrows Palmer's car to test his theory on Radcliffe, but is killed before reaching him.

Believing that he himself must have been the intended target, Palmer goes home to collect his belongings, and there discovers the body of the second CIA agent. When he returns to the office, the IPCRESS file is missing from his desk. Certain that he is being set up, Palmer tells Dalby what has happened and that he suspects Ross took the file, which Ross had previously asked him to microfilm. Dalby tells him to leave town for a while.

On the train to Paris, Palmer is kidnapped and wakes up imprisoned in a cell in Albania. After several days without sleep, food and warmth, Grantby reveals himself as his kidnapper. Having read the file, Palmer realises that they are preparing to brainwash him. He uses pain to distract himself, but after many sessions under stress from disorientating images and loud, meaningless electronic sounds, he succumbs. Grantby then instills a trigger phrase that will make Palmer follow any commands given to him.

Palmer eventually manages to escape to the street, and learns he is actually in London. He phones Dalby, who is in Grantby's company at the time. Dalby uses the trigger phrase and gets Palmer to call Ross to the warehouse.

As Dalby and Ross arrive, Palmer holds them both at gunpoint. Dalby accuses Ross of killing Carswell; Ross tells Palmer that he had been suspicious of Dalby and was investigating him. Dalby uses the trigger phrase again and commands Palmer to "Shoot the traitor now". Palmer wavers; his hand strikes against a piece of metal and the pain reminds him of his conditioning. Dalby goes for his gun and Palmer shoots him.

Ross remarks that in choosing Palmer for the assignment, he had hoped that Palmer's tendency to insubordination would be useful. When Palmer reproaches Ross for endangering him, he is told that it is part of his job.

Main cast

- Michael Caine as Harry Palmer

- Guy Doleman as Colonel Ross

- Nigel Green as Major Dalby

- Sue Lloyd as Jean Courtney

- Gordon Jackson as Carswell

- Aubrey Richards as Dr. Radcliffe

- Frank Gatliff as Eric Grantby (Bluejay)

- Thomas Baptiste as Barney

- Oliver MacGreevy as Housemartin

- Freda Bamford as Alice

- Pauline Winter as Charlady

- Anthony Blackshaw as Edwards

- Barry Raymond as Gray

- David Glover as Chilcott-Oakes

- Stanley Meadows as Inspector Keightley

- Peter Ashmore as Sir Robert

- Michael Murray as Raid Inspector

- Anthony Baird as Raid Sergeant

- Tony Caunter as O.N.I. man

- Douglas Blackwell as Murray

- Glynn Edwards as Police Station Sergeant

Production and contrast with Bond franchise

The film was intended as an ironically downbeat alternative portrait of the world of spies portrayed in the successful and popular James Bond films, even though one of the producers and others in the production team were also responsible for the Bond franchise. In contrast to Bond's public school background and playboy lifestyle, Palmer is a working class Londoner who lives in a Notting Hill bedsit and has to put up with red tape and inter-departmental rivalries. When appointed to a new post, he immediately asks whether he will get a pay rise (by contrast, Bond's salary is hardly mentioned and he only goes to the best hotels, often using the presidential suite). The action is set entirely in "a gritty, gloomy, decidedly non-swinging" London with humdrum locations.[3] And although Palmer is, like Bond, a gourmet, he shops in a supermarket.

In this respect, it is a tribute to the complexity and flexibility of the mind of Harry Saltzman, who was an acknowledged master of proposing "bigger and more extravagant ideas" for Bond films according to the MGM Home Entertainment documentary Harry Saltzman: Showman. Five prominent members of the production team – producer Harry Saltzman, executive producer Charles Kasher (who also produced the sequel Funeral In Berlin), film editor Peter R. Hunt, composer John Barry and production designer Ken Adam – also worked on the James Bond film series, and projects like this ultimately led to Saltzman's departure from Eon Productions and his sale of Danjaq, LLC to United Artists in 1975.

Harry Saltzman gave Jimmy Sangster a copy of the novel to read. Sangster enjoyed the book and was eager to adapt the novel, and suggested Michael Caine play the role and Sidney J. Furie direct. However, Saltzman would not commit to the timeframe that Sangster insisted upon.[4] Ken Hughes wrote a script which Saltzman rejected.[5]

Ipcress had two immediate sequels: Funeral in Berlin (1966) and Billion Dollar Brain (1967). Decades later Michael Caine returned to his Harry Palmer character in Harry Alan Towers's Bullet to Beijing (1995) and Midnight in Saint Petersburg (1996).

The film was shot in Techniscope, an economical 2 perf (each frame taking up only two perforations of film length rather than four or more) widescreen format introduced by Technicolor Italia in 1963. Techniscope allowed a greater depth of field because it was shot with shorter focal length lenses than the anamorphic widescreen processes. This allowed cinematographer Otto Heller to construct images in deep focus, shooting behind objects and allowing both the objects in the foreground and the action taking place in the background to be in focus.[6]

The complex electronic sound effect of the brain-washing process was conceived by sound engineer Norman Wanstall and created by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.[7]

Harry Palmer character

Harry Palmer character page: Harry Palmer

The protagonist of Deighton's novel was nameless, but in Chapter 5 he remarks, "My name isn't Harry, but in this business it's hard to remember whether it ever had been." In the opening scenes of the film, Palmer is shown to care little for authority, to indulge in quick repartee and to have an interest in good food. Newspaper cuttings shown in Palmer's kitchen are actually cookery articles written for The Observer by Deighton, an accomplished cook and cookery writer.[8][9] In a scene where Palmer prepares a meal, the hands in close-up are Deighton's.[6]

Soundtrack

John Barry, who had worked on all the Bond films at the time, composed the soundtrack. As opposed to the electric guitar which carried the melody in The James Bond Theme, Barry made prominent use of a cimbalon played by John Leach.[10] The main theme entitled A Man Alone was released in several cover versions including a vocal song by Pat Boone.

Reception

When the film premiered at the Leicester Square Theatre in London on 18 March 1965, the film critic for The Times had mixed feelings about it. While enjoying the first part of the film, and generally praising Michael Caine, the critic found the second half bewildering to the extent that the characters "cease to be pleasantly mystifying and become just irritatingly obscure."[1] A review in Variety was largely positive, describing the film as "anti-Bond" for its unglamorous depiction of espionage, and praising Caine's understated performance but criticizing the sometimes "arty-crafty" camera work.[11]

Subsequently, the film has come to be recognized as a classic. The Ipcress File is included on the British Film Institute's BFI 100, a list of 100 of the best British films of the 20th century, at No. 59,[12] and currently holds a "Fresh" rating of 100% at Rotten Tomatoes.

Awards

The film won the BAFTA Award for Best British Film, and Ken Adam won the award for 'Best British Art Direction, Colour'.[13]

Screenwriters Bill Canaway and James Doran received a 1966 Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America for Best Foreign Film Screenplay.

The film was entered into the 1965 Cannes Film Festival, and was nominated for the Palme d'Or award.[14]

References

- ^ a b The Times, 18 March 1965, page 9: Film review of The Ipcress File – read 13 September 2013 in The Times Digital Archive

- ^ This figure consists of anticipated rentals accruing distributors in North America. See "Top Grossers of 1965", Variety, 5 January 1966 p 36

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (13 January 2006). "The Ipcress File". The Guardian. London. p. 8.

- ^ Sangster, Jimmy (1997). Do You Want It Good or Tuesday?: From Hammer Films to Hollywood! : A Life in the Movies : An Autobiography. Midnight Marquee Press. p. 78. ISBN 9781887664134.

- ^ Sheffy, Pearl (29 January 1966). "The Man who got the Bond Going". Calgary Herald. pp. unnumbered.

- ^ a b Lewis, Paul. "The Ipcress File Blu-ray review". Rewind/DVDCompare. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ "Interview with Norman Wanstall". James Bond Radio. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ https://www.fantasticfiction.com, webmaster@fantasticfiction.com -. "Action Cook Book by Len Deighton". www.fantasticfiction.co.uk.

{{cite web}}: External link in|last= - ^ Deighton, Len (5 December 1965). "Len Drghton's Cookstrip Cook Book". B. Geis Associates – via Amazon.

- ^ "500". The Telegraph.

- ^ Staff, Variety (1 January 1965). "The Ipcress File".

- ^ "The BFI 100 – A selection of the favourite British films of the 20th century".

- ^ "The British Film Designers Guild :: Helpful Information".

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: The Ipcress File". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

External links

- Template:BFI Explore

- The Ipcress File at the BFI's Screenonline

- The Ipcress File at IMDb

- The Ipcress File at the TCM Movie Database

- The Ipcress File at AllMovie

- The Ipcress File at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Ipcress File - Photos

- Kees Stam's Harry Palmer movie site and filming locations

- The Deighton Dossier

- The Ipcress File Blu-ray review

- 1965 films

- British films

- British spy films

- Cold War spy films

- 1960s spy films

- 1960s thriller films

- Political thriller films

- Films based on British novels

- Films based on mystery novels

- Films set in London

- Films directed by Sidney J. Furie

- Films shot at Pinewood Studios

- Mind control in fiction

- Films scored by John Barry (composer)

- Best British Film BAFTA Award winners

- Films produced by Harry Saltzman

- Cold War in popular culture

- Universal Pictures films