Transmembrane protein 89

| TMEM89 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | TMEM89, transmembrane protein 89 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | MGI: 1916634; HomoloGene: 52857; GeneCards: TMEM89; OMA:TMEM89 - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Transmembrane protein 89 (TMEM89) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TMEM89 gene.

Gene

[edit]Structure

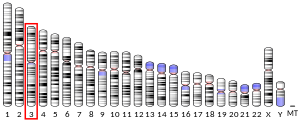

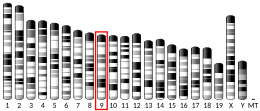

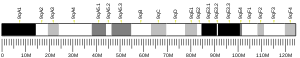

[edit]The TMEM89 gene is found on the minus strand of chromosome 3 (3p21.31) from 48,658,192 to 48,659,288 and is 1,011 nucleotides long.[5][6] The gene has two exons.[5][6] These two exons are not predicted to be alternatively spliced.[5][6]

Gene expression

[edit]The TMEM89 gene is most highly expressed in the testis.[5][6] TMEM89 is also found to be expressed at low levels in other tissues such as the stomach, kidneys, heart, ovaries, thyroid, colon, bone marrow, and in adrenal tissues.[5] This gene is also expressed in fetal heart, stomach, kidney, and intestine tissues.[5] Immunohistochemistry data has also found TMEM89 located in the cell membranes of the colon, fallopian tube, kidney, and testis tissues.[7][8] Expression of the TMEM89 gene has also been found in low amounts in the brain tissue from a mouse cerebellum.[9]

Gene expression neighborhood

[edit]Human TMEM89 is a part of the Human Protein Atlas expression cluster 23: SpermatidS - Flagellum & Golgi organization.[7][10] The 15 closest expression neighbors include OR4M1, ANTXRL, TGIF2LX, CPXCR1, C3orf84, CXorf66, CLDN17, C11orf94, USP50, SPDYE4, MMP20, SSMEM1, SPMAP1, SPACA1, and LYZL1.[10]

Differential gene expression

[edit]TMEM89 expression is much higher in amniotic fluid derived hAKPC-P cells compared with immortalized hIPod line cells.[11] TMEM89 expression is higher in cells that have macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) knocked down compared to the control.[12] TMEM89 expression is the lowest in cardiomyocytes from human embryonic stem cells, compared to expression in human embryonic stem cells, embryoid bodies with beating cardiomyocytes, and cardiomyocytes from fetal hearts.[13]

Clinical significance

[edit]Gene expression of TMEM89 was found to be upregulated in upper tract urothelial carcinomas, and therefore predicted as a possible biomarker secretory protein for these types of carcinomas.[14] The TMEM89 gene was found to be a potential modifier of autism spectrum disorder severity in a SNP analysis.[citation needed] Gene expression of TMEM89 was also used in a model that predicted the risk score for a potential relapse in stage 1 testicular germ cell tumors.[15]

Protein

[edit]Structure

[edit]Primary

[edit]The human TMEM89 protein is 159 amino acids long.[5] This protein has a molecular mass of ~17.5kDa and an isoelectric point of ~10 pI.[6][22] Proteins with a more basic pI are usually associated with the mitochondria or the plasma membrane and have fewer protein interactions.[23][24] The protein structure contains two topological domains (extracellular and cytoplasmic) and a helical transmembrane domain.[17][25][26] The human TMEM89 protein is rich in the amino acids histidine, leucine, and tryptophan.[18] The amino acids aspartate, asparagine, and phenylalanine are present in low amounts in the human TMEM89 protein.[18] Amino acid patterns such as ED are present in the human TMEM89 protein at low amounts, while the pattern KR-ED is present in high amounts.[18] Within the extracellular domain of the human TMEM89 protein, there are 3 cysteines with regular spacing.[18] In the cytoplasmic domain, there are two positive amino acid runs from amino acids 3-5 and 25-27.[18] These different amino acid patterns and protein domains can be visualized in the figures to the right.

Secondary

[edit]The TMEM89 protein is only made up of α-helices and strands.[27][28] The α-helices are distributed all throughout the protein in all three domains.[27][28]

Tertiary

[edit]The tertiary structure of Human TMEM89 was predicted using Alphafold and I-Tasser software.[27][28] These structures can be seen on the right.

Post-translational modifications

[edit]The TMEM89 protein has a predicted N-myristylation site from amino acids 47-52, a predicted Src homology 3 (SH3) binding domain from amino acids 106-111, and one conserved predicted phosphorylation site at amino acid S117.[19][21][20] N-myristylation is a protein lipid modification that has roles in protein-protein interactions, cell signaling, and targeting proteins to endomembranes and the plasma membrane.[30] Proteins with SH3 binding domains are usually involved in signal transduction pathways, cytoskeleton organization, membrane trafficking, or organelle assembly.[31] Protein phosphorylation is an important process involved with signal transduction, protein synthesis, cell division, cell growth, development, and aging.[32]

Interactions

[edit]The human TMEM89 protein interacts with the proteins C4A, RBM15B, GOLGA6A, PFKFB4, DOCK3, MAPKAPK3, ZNF557, and ZBTB47.[35][36]

Homologs

[edit]Orthologs

[edit]Orthologs of TMEM89 are only found in mammals.[5] The only mammalian taxon that does not contain a TMEM89 ortholog is the monotremes.

Below is a table with information on some of the orthologs of human TMEM89. These orthologs were used to make the multiple sequence alignment and N-myristylation site alignment to the right.

| Genus and Species | Common Name | Taxon | Date of Divergence (MYA) | NCBI Accession Number | Sequence Length (aa) | % Identity | % Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens | Humans | Primate | 0 | NP_001008270.1 | 159 | 100 | 100 |

| Castor canadensis | American beaver | Rodentia | 87 | XP_020018275.1 | 158 | 73.1 | 81.2 |

| Urocitellus parryii | Arctic ground squirrel | Rodentia | 87 | XP_026239733.1 | 155 | 66.0 | 74.8 |

| Orcinus orca | Orca | Artiodactyla | 94 | XP_004283952.1 | 159 | 71.9 | 80.0 |

| Bos taurus | Cow | Artiodactyla | 94 | NP_001104538.1 | 159 | 63.5 | 73.5 |

| Odobenus rosmarus divergens | Pacific walrus | Carnivora | 94 | XP_004399365.2 | 159 | 67.9 | 77.4 |

| Canis lupus familiaris | Dog | Carnivora | 94 | XP_038283783.1 | 159 | 65.6 | 76.2 |

| Talpa occidentalis | Spanish mole | Eulipotphyla | 94 | XP_037376292.1 | 162 | 66.7 | 75.3 |

| Condylura cristata | Star-nosed mole | Eulipotphyla | 94 | XP_004676653.1 | 162 | 63.0 | 74.1 |

| Pteropus alecto | Black flying fox | Chiroptera | 94 | XP_006909233.1 | 156 | 65.2 | 74.5 |

| Desmodus rotundus | Common vampire bat | Chiroptera | 94 | XP_024421609.1 | 159 | 63.8 | 74.4 |

| Ceratotherium simum simum | Southern white rhinoceros | Perissodactyla | 94 | XP_004419716.1 | 159 | 64.2 | 78.0 |

| Equus caballus | Horse | Perissodactyla | 94 | XP_003363167.2 | 207 | 49.8 | 58.9 |

| Manis javanica | Malayan pangolin | Pholidota | 94 | KAI5937412.1 | 158 | 53.8 | 67.5 |

| Manis pentadactyla | Chinese pangolin | Pholidota | 94 | XP_036733472.1 | 158 | 53.1 | 66.0 |

| Orycteropus afer afer | Aardvark | Tubulidentata | 99 | XP_007953489.1 | 160 | 68.9 | 77.0 |

| Loxodonta africana | African bush elephant | Proboscidea | 99 | XP_003409726.1 | 160 | 68.8 | 79.4 |

| Dasypus novemcinctus | Nine-banded armadillo | Cingulata | 99 | XP_004451990.1 | 157 | 67.5 | 75.0 |

| Sarcophilus harrisii | Tasmanian devil | Dasyuromorphia | 160 | XP_031794457.1 | 168 | 41.0 | 52.2 |

| Trichosurus vulpecula | Common brushtail possum | Diprotodontia | 160 | XP_036595517.1 | 168 | 40.8 | 51.4 |

Conserved regions

[edit]Regions within the cytoplasmic and extracellular domains of the human TMEM89 protein seem to be the most conserved, as seen in figures on the right.[34][37] Some of these conserved amino acids are part of α-helices in the cytoplasmic and extracellular regions.[34][37]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000183396 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000025652 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sayers EW, Bolton EE, Brister JR, Canese K, Chan J, Comeau DC, et al. (January 2022). "Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information". Nucleic Acids Research. 50 (D1): D20–D26. doi:10.1093/nar/gkab1112. PMC 8728269. PMID 34850941.

- ^ a b c d e Stelzer G, Rosen N, Plaschkes I, Zimmerman S, Twik M, Fishilevich S, et al. (June 2016). "The GeneCards Suite: From Gene Data Mining to Disease Genome Sequence Analyses". Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. 54 (1): 1.30.1–1.30.33. doi:10.1002/cpbi.5. PMID 27322403. S2CID 26619932.

- ^ a b "The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2022-12-15.

- ^ Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. (January 2015). "Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome". Science. 347 (6220): 1260419. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. PMID 25613900. S2CID 802377.

- ^ Daigle TL, Madisen L, Hage TA, Valley MT, Knoblich U, Larsen RS, et al. (July 2018). "A Suite of Transgenic Driver and Reporter Mouse Lines with Enhanced Brain-Cell-Type Targeting and Functionality". Cell. 174 (2): 465–480.e22. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.035. PMC 6086366. PMID 30007418.

- ^ a b Karlsson M, Zhang C, Méar L, Zhong W, Digre A, Katona B, et al. (July 2021). "A single-cell type transcriptomics map of human tissues". Science Advances. 7 (31): eabh2169. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.2169K. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abh2169. PMC 8318366. PMID 34321199.

- ^ Da Sacco S, Lemley KV, Sedrakyan S, Zanusso I, Petrosyan A, Peti-Peterdi J, et al. (12 December 2013). "A novel source of cultured podocytes". PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e81812. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...881812D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0081812. PMC 3861313. PMID 24349133.

- ^ Liu L, Ji C, Chen J, Li Y, Fu X, Xie Y, et al. (June 2008). "A global genomic view of MIF knockdown-mediated cell cycle arrest". Cell Cycle. 7 (11): 1678–1692. doi:10.4161/cc.7.11.6011. PMID 18469521. S2CID 28241410.

- ^ Cao F, Wagner RA, Wilson KD, Xie X, Fu JD, Drukker M, et al. (22 October 2008). "Transcriptional and functional profiling of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes". PLOS ONE. 3 (10): e3474. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3474C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003474. PMC 2565131. PMID 18941512.

- ^ Li Y, He S, He A, Guan B, Ge G, Zhan Y, et al. (May 2019). "Identification of plasma secreted phosphoprotein 1 as a novel biomarker for upper tract urothelial carcinomas". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 113: 108744. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108744. PMID 30844659. S2CID 73493678.

- ^ Zhou JG, Yang J, Jin SH, Xiao S, Shi L, Zhang TY, et al. (30 July 2020). "Development and Validation of a Gene Signature for Prediction of Relapse in Stage I Testicular Germ Cell Tumors". Frontiers in Oncology. 10: 1147. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.01147. PMC 7412879. PMID 32850325.

- ^ "Six-Frame Translation". www.bioline.com. Retrieved 2022-12-15.

- ^ a b Bateman A, Martin M, Orchard S, Magrane M, Agivetova R, Ahmad S, et al. (UniProt Consortium) (January 2021). "UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2021". Nucleic Acids Research. 49 (D1): D480–D489. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa1100. PMC 7778908. PMID 33237286.

- ^ a b c d e f Brendel V, Bucher P, Nourbakhsh IR, Blaisdell BE, Karlin S (March 1992). "Methods and algorithms for statistical analysis of protein sequences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 89 (6): 2002–2006. Bibcode:1992PNAS...89.2002B. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.6.2002. PMC 48584. PMID 1549558.

- ^ a b c d Pagni M, Ioannidis V, Cerutti L, Zahn-Zabal M, Jongeneel CV, Hau J, et al. (July 2007). "MyHits: improvements to an interactive resource for analyzing protein sequences". Nucleic Acids Research. 35 (Web Server issue): W433–W437. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm352. PMC 1933190. PMID 17545200.

- ^ a b c "Kinexus PhosphoNET". www.phosphonet.ca.

- ^ a b c Kumar M, Michael S, Alvarado-Valverde J, Mészáros B, Sámano-Sánchez H, Zeke A, et al. (January 2022). "The Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource: 2022 release". Nucleic Acids Research. 50 (D1): D497–D508. doi:10.1093/nar/gkab975. PMC 8728146. PMID 34718738.

- ^ Bjellqvist B, Hughes GJ, Pasquali C, Paquet N, Ravier F, Sanchez JC, et al. (October 1993). "The focusing positions of polypeptides in immobilized pH gradients can be predicted from their amino acid sequences". Electrophoresis. 14 (10): 1023–1031. doi:10.1002/elps.11501401163. PMID 8125050. S2CID 38041111.

- ^ Baskin EM, Bukshpan S, Zilberstein GV (May 2006). "pH-induced intracellular protein transport". Physical Biology. 3 (2): 101–106. Bibcode:2006PhBio...3..101B. doi:10.1088/1478-3975/3/2/002. PMID 16829696. S2CID 41599078.

- ^ Kiraga J, Mackiewicz P, Mackiewicz D, Kowalczuk M, Biecek P, Polak N, et al. (June 2007). "The relationships between the isoelectric point and: length of proteins, taxonomy and ecology of organisms". BMC Genomics. 8 (1): 163. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-8-163. PMC 1905920. PMID 17565672.

- ^ a b c Hirokawa T, Boon-Chieng S, Mitaku S (1998-05-01). "SOSUI: classification and secondary structure prediction system for membrane proteins". Bioinformatics. 14 (4): 378–379. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/14.4.378. PMID 9632836.

- ^ a b Omasits U, Ahrens CH, Müller S, Wollscheid B (March 2014). "Protter: interactive protein feature visualization and integration with experimental proteomic data". Bioinformatics. 30 (6): 884–886. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt607. hdl:20.500.11850/82692. PMID 24162465.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, et al. (August 2021). "Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold". Nature. 596 (7873): 583–589. Bibcode:2021Natur.596..583J. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. PMC 8371605. PMID 34265844.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yang J, Zhang Y (July 2015). "I-TASSER server: new development for protein structure and function predictions". Nucleic Acids Research. 43 (W1): W174–W181. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv342. PMC 4489253. PMID 25883148.

- ^ a b c d e f Wang Y, Geer LY, Chappey C, Kans JA, Bryant SH (June 2000). "Cn3D: sequence and structure views for Entrez". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 25 (6): 300–302. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01561-9. PMID 10838572.

- ^ Udenwobele DI, Su RC, Good SV, Ball TB, Varma Shrivastav S, Shrivastav A (2017-06-30). "Myristoylation: An Important Protein Modification in the Immune Response". Frontiers in Immunology. 8: 751. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00751. PMC 5492501. PMID 28713376.

- ^ Kumar M, Michael S, Alvarado-Valverde J, Mészáros B, Sámano-Sánchez H, Zeke A, et al. (January 2022). "The Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource: 2022 release". Nucleic Acids Research. 50 (D1): D497–D508. doi:10.1093/nar/gkab975. PMC 8728146. PMID 34718738.

- ^ Ardito F, Giuliani M, Perrone D, Troiano G, Lo Muzio L (August 2017). "The crucial role of protein phosphorylation in cell signaling and its use as targeted therapy (Review)". International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 40 (2): 271–280. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2017.3036. PMC 5500920. PMID 28656226.

- ^ Liu W, Xie Y, Ma J, Luo X, Nie P, Zuo Z, et al. (October 2015). "IBS: an illustrator for the presentation and visualization of biological sequences". Bioinformatics. 31 (20): 3359–3361. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv362. PMC 4595897. PMID 26069263.

- ^ a b c d Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, et al. (October 2011). "Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega". Molecular Systems Biology. 7 (1): 539. doi:10.1038/msb.2011.75. PMC 3261699. PMID 21988835. S2CID 3084940.

- ^ Huttlin EL, Ting L, Bruckner RJ, Gebreab F, Gygi MP, Szpyt J, et al. (July 2015). "The BioPlex Network: A Systematic Exploration of the Human Interactome". Cell. 162 (2): 425–440. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.043. PMC 4617211. PMID 26186194.

- ^ Ghani M, Reitz C, Cheng R, Vardarajan BN, Jun G, Sato C, et al. (November 2015). "Association of Long Runs of Homozygosity With Alzheimer Disease Among African American Individuals". JAMA Neurology. 72 (11): 1313–1323. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.1700. PMC 4641052. PMID 26366463.

- ^ a b c d e Madden, Thomas L.; Tatusov, Roman L.; Zhang, Jinghui (1996), "Applications of network BLAST server", Computer Methods for Macromolecular Sequence Analysis, Methods in Enzymology, vol. 266, Elsevier, pp. 131–141, doi:10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66011-x, ISBN 978-0-12-182167-8, PMID 8743682, retrieved 2022-12-15

- ^ Kumar S, Suleski M, Craig JM, Kasprowicz AE, Sanderford M, Li M, et al. (August 2022). "TimeTree 5: An Expanded Resource for Species Divergence Times". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 39 (8): msac174. doi:10.1093/molbev/msac174. PMC 9400175. PMID 35932227.

- ^ Needleman SB, Wunsch CD (March 1970). "A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequence of two proteins". Journal of Molecular Biology. 48 (3): 443–453. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(70)90057-4. PMID 5420325.

- ^ "drawtree". evolution.genetics.washington.edu. Retrieved 2022-12-15.