User:HNlander/draft01

Political repression against ethnic Chinese in Russian Far East during the Great Purge

During the Great Purge in Russian Far East, ethnic Chinese underwent forced migration and political repression by the Soviet Communist Party. These Chinese included both the citizens of the Republic of China, and the Soviet citizens who were identified as ethnic Chinese (Китаец). Despite the Chinese origin, the Taz were free from repression as they were recognized as a different ethnic group from the Chinese. [1]: 172,173

By the 1940s, Chinese had became almost extinct in Russian Far East, despite the fact there were more than 200 thousands Chinese before the October Revolution in 1921, with detailed history still needed to be uncovered in Soviet records.[2] As local East Asians were forced to leave the area during the period, Europeans were also forced to migrate to Far East from Europe and Siberia, and eventually became dominant in the local population.[3]

Among the East Asian victims of the repression, there were at least 27,558 ethnic Chinese who were directly involved in the migration and repression directly and most of them were citizens of the Republic of China. [4]: 238 3,794 of them were released by the Soviet Government,[5] 3,922 executed,[6] 17,175 forced to migrate or banished, the rest detained in various places including Gulag.[7][8] In 1937, there were only 26,607 ethnic Chinese Soviet citizens in Far East[9].

On 30th October 2012, two monuments in memory of the Chinese and Korean victims were set up by Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights of Russia in Moscow and Blagoveshchensk.[10]

Background

[edit]Repression against Chinese during the civil war

[edit]In Russian Far East, the repression against ethnic Chinese began early before the Great Purge. As the October Revolution evoked Russian Civil War, ethnic Chinese were discriminated and repressed against by multiple parties of the war.

According to Chinese diplomatic documents, the dead bodies of Chinese nationals were left in the air where the White Army had passed, some wound by guns or blades, some frozen to death due after being robbed. The Red Army, accordingly, was also poorly disciplined, raping and torturing the Chinese, setting the Chinese houses and goods on fire. Radicals regarded anyone who could not speak Russian as spies, robbing their possessions and killing their lives. The allied army randomly checked the belongings of the Chinese workers and if they think anything in suspicion, they would regard the workers as communist and kill them without interrogation. [11]: 112–113 An extreme example was the case of Chinese businessmen from Changyi, Shandong, who were robbed and humiliated in Russia.[12] These series of events made some Chinese return to China or move to other countries.[13]

Racial tension under the New Economic Policy

[edit]The Communist Party started to carry out what was called New Economic Policy after the civil war, which soon attracted Chinese migrants back to Far East lacking in working forces. Although the Government also migrate 66,202 from Europe to the region, the rising number of Chinese made a tremendous impact on the local economy[14][15][16]. By the late 1920s, the Chinese had controlled more than half commerce places and share of trade in Far East. 48.5% of grocery retails, 22.1% of food, beverage, tobacco were sold by Chinese, 10.2% of the restaurants were run by Chinese.[17][18]

Tension escalated as fake and low-quality goods sold by some Chinese businessmen stereotyped the Chinese as swindlers and thieves among the local Russians.[4]: 276 On 1st June 1930, a small-scale armed conflict broke out between the two races in Leninskiy, Vladivostok, which injured 27, 3 permanently disabled. The conflict triggered further racial conflicts. Russians in the region viewed most Chinese new-comers as non-Russian-speakers, misers, renegers and cheaters, while the Chinese regarded the Russians as addicts to violence and brutality, frequent violent threateners, unreasonable people, and fools.[4]: 288–230

Governmental actions against the Chinese

[edit]The closure of the Chinese community also led to repugnance of the Government and the local Russians. District 18 of Vladivostok, densely populated by the Chinese and called "the Millionaires' village" (百万庄) in Chinese, was free from governmental control except for taxation. The Chinese were organized according to their origins in China, gangs, and religious groups, which was independent of the Soviet society. Thus, the Soviet Government regarded the Chinese as a potential threat as the community could cover the Japanese espionages.[19]

Since the late 1920s, the Soviet Union tautened the control along the Sino-Soviet border with following measures: 1) stricter security check for entry into the Union; 2) taxing the outbound packages, whose worth should be less than 300 rubles, at a rate of 34%. When the Chinese were leaving the Union, they would need to pay a 14-ruble outbound fee and to be checked nakedly. Remittance of the Chinese was restricted. Extra taxation, including that of business license, business, income, profits, private debts, docks, poverty, school and etc., was assigned to the Chinese and their properties. They were forced to join the local workers' union, as a premise of their jobs. [20]: 28

In 1926, People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs resolved to use any means to stop Chinese and Koreans migrating into Soviet territory, as they were regarded to cause serious danger to the Soviet Union. Koreans were relocated from Far East, while measures were take to "squeeze out" the Chinese from the border area.[11]: 116–117

1929 Sino-Soviet conflict

[edit]

In 1928, Arsenyev Mikhail Mikhailovich (Арсеньев Михаил Михайлович), Staff Colonel of Red Army Headquarter, submitted a report to Far Eastern Commission, advising that free migration from China and Korea in the areas bordering the countries should be stopped, and that the area should be filled with migrants from Siberia and Europe instead. [2][11]

As the Sino-Soviet conflicts over the Chinese Eastern Railway worsened the bilateral relation, the Soviet Government began to stop Chinese crossing the border since 1931.[21] All Soviet diplomats in China were called back, all Chinese diplomats to Soviet Union expelled and train between China and Russia forced to be out of service. [20]: 30

The Soviet Government forced the Chinese to move to Northeast China. Thousands of Chinese in Irkutsk, Chita and Ulan-Ude were arrested due to reasons including breach of local orders and tax evasion. When they were to leave Russia, any Chinese to crash the border with more than 30 rubles in cash will need to pay the surplus to the authority. Any Chinese with more than 1,000 rubles in cash to cross the border will be arrested, with all the money confiscated.

The Chinese were massively detained. According to Shanghai newspaper Shen Bao on 24th July 1929, "Around a thousand Chinese who lived in Vladivostok were detained by the Soviet authority. They were all said to be bourgeoisie."[22] On 12 August, the newspaper stated that there were still 1,600-1,700 Chinese detained in Vladivostok, supplied with a piece of rye bread daily and undergoing various tortures.[23] On 12 August, the newspaper stated that those detained in Khabarovsk only had a bread soup for meal daily, among which a lot of people had hanged them due to starvation.[24] On 14th September, the newspaper stated that another thousand of Chinese in Vladivostok were arrested, with almost no Chinese remaining in the city. [25] On 15th September, the newspaper continued that Vladivostok had arrested more than 1,000 Chinese during the 8th and 9th of September, and that estimatedly there were more than 7,000 Chinese in jail in the city.[26] On 21st September, the newspaper said, "the Government in Russian Far East cheated the arrested Chinese, and forced them to construct the railway between Heihe and Khabarovsk. The forced workers only only two pieces of rye bread to eat daily. If they work with any delay, they will be whipped, making them at the edge of living and dead."[27][20]: 31

Although after signing the Treaty of Khabarovsk, the Soviet Government released most arrested Chinese, considering that the Chinese had been severely tortured by the Soviet Government, that the confiscated possessions of the Chinese were not returned, difficult situations among the workers and businessmen, the high prices of goods, and the unaffordable living costs, the Chinese all returned to China afterwards.[20]: 31

Great Purge

[edit]

Listed as a target for Great Purge

[edit]On 21st August 1937, the deportation of Koreans, the largest ethnic group of all Asians in Russian Far East, began being carried out.[28] On 23rd October, the Chinese were listed as a target of the purge after the Polish, the German and the Koreans, as announced by Order 693 of People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs.[29]Nikolai Yezhov permitted secret arrests of "all suspicious of spies and saboteurs".[29] On 10th November, the Republic of China Consulate in Chita reported to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that the Soviet was migrating 30,000 Europeans to Siberia and Far East monthly to strengthen defense and economic construction in the region, and that to save space for the European migrants and to avoid Chinese or Korean collusion with Japan and Manchukuo, the policy to remove Koreans and Chinese was enforced.[30]

Plan to suppress Chinese "traitors and spies"

[edit]

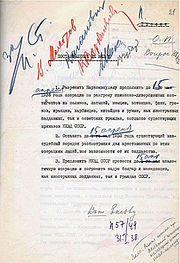

On 22nd December, Nikolai Yezhov ordered Genrikh Lyushkov, Chair of People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) in Far East, to arrest all Chinese with provocation and terrorist aims with no regard to their nationality.[31] On the following day (23rd), Yezhov published the Plan to Suppress Chinese Traitors and Spies, and order to remove any hiding places for the Chinese and other people, to search the places with care, and to arrest both tenants and landlords. Any anti-Soviet Chinese, Chinese spies, Chinese smugglers and Chinese criminals of Soviet nationality should be tried by a three-people group led by Lyushkov, anti-Soviet Chinese and Chinese spies to be suppressed. Any foreigners involved in these kinds of events should be expelled after tried. Any wanted suspicious was prohibited from living in Far East, Chita, and Irkutsk.[32][33]

Mikhail Iosifovich Dimentman led NKVD in Primorsky Krai to carry out the night purge of the Polish, the German, the Koreans and the Chinese in Vladivostok streets on 24th December 1937. The Catholic Polish celebrating the Christmas Eve were almost all captured at that night and then sent to Central Siberia.[34]: 171 7 neighborhoods residing the Korean were purged during three days and two nights afterwards, with all defenders killed. [35][36][34]: 173 District 18 populated by Chinese was once destroyed in 1936 and rebuilt by Chinese migrants. On that night, shootouts broke out in the neighborhood, killing 7 Soviets and 434 Chinese.[34]: 174 The Government spent 7 months to reconstruct the whole neighborhood after the conflict. Russian historian Oleg Khlevnyuk describes the night as "a racial massacre based on narrow Russian nationalism in the name of socialism".[34]: 175 Corpses of the Chinese victims were re-discovered on 8th June 2010 where used to be District 18, on 8th June 2010.[37]

On 29th December, Primorsky Krai launched a purge against the Chinese, leading to 853 arrests according to the Krai Governmental records.[38] The Republic of China consulates in Khabarovsk and Blagoveshchensk reported more than 200 and 100 Chinese arrested respectively. [39]During 12-13th January 1938, another 20 and more Chinese were reportedly arrested in Blagoveshchensk.[39]

Interferences by the Chinese Consulates and media

[edit]On 10th January 1938, Yu Ming, Charge-D of the Chinese embassy in Moscow, Soviet Union lodge representations to the Soviet Union, urging the authority to release the Chinese. The Chinese request to meet the chief officer of the Department of Far East of People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs on the following day (11th January 1938) was declined by the officer who claimed to be sick.[40] On 13th January, some Chinese reported to Chinese consulates in Vladivostok and Khabarovsk that the detained Chinese were starving and even tortured to death, yet the NKDA reject any meeting or food donation by the Chinese consulates.[41] On 28th January, the Chinese Consulate in Vladivostok reported to the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, "how could we believe that (the Soviet authority) said the Chinese all committed espionage!"

The Politburo extended the purges against nationalists including the Chinese by passing the Repressions against "national lines" in the USSR (1937-1938), which began to be carried out in February. The Soviet abuse of the Chinese was reported by the Central Daily News on 6th February.[42] On 14th, the Chinese Consulate in Vladivostok reported to the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, "the Soviet robbed everything, especially money and possessions; if they are hidden somewhere, the Chinese would be extorted by tortures, numerous people killed by such detention, which was miserable and harsh to an extreme."[43] On 17th, the Chinese Consulate in Khabarovsk protested against the torture during interrogation, urging the Soviet Union to release the Chinese. On 19th, the Central Daily News again protested against the Soviet abuse of the Chinese.[44] On 21st, Hong Kong-based Kung Sheung Daily News re-posted a Japanese newspaper coverage of the event, expressing outrage against the deeds of the Soviet Union.[45] On 22nd, the Chinese Consulate in Khabarovsk reported another hundred of innocent Chinese arrested over the previous night by NKVD and that it was heard previously arrested Chinese were forced to work in those remote, cold areas.[46] On 2nd March, the Chinese Consulate in Vladivostok stated, "the Soviet authority searched for the Chinese day and night, arresting the Chinese even when they were at work. The Soviet was so aggressive that there was no space for any concession. The deeds was as brutal as the exclusion of China in 1900, during which many were drowned in the Heilongjiang River. Recalling the miserable history makes people tremble with fear."[47]

After times of massive arrests, there were only more than a thousand Chinese in Vladivostok. The Soviet authority stopped the search and arrest for a month. After the Chinese sheltered by the Chinese Consulate all left the Consulate, the Soviet authority restarted to search for and arrest the Chinese. As the Soviet had established tremendous checkpoints around the Chinese Consulate, the Chinese were unable to return to the Consulate for help, which made almost all the Chinese in Vladivostok arrested.[48][49] The second and third massive search-and-seizure operation arrested 2,005 and 3,082 Chinese respectively. On 7th May, the Chinese Consulate in Vladivostok reported 7 to 8 thousand Chinese under detention. Local prisons were filled by the Chinese, which, added by tortures during interrogations, often caused deaths.[50]

Wang Chonghui, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the China Nationalist Government, and Ivan Trofimovich, Soviet Ambassador to China, had a 4-day talk over the detention of the Chinese nationals in Russian Far East since 18th April, which was concluded with 7 articles:[51][52]

- the Soviet Union is willing to pay the expenditure of relocation of the Chinese nationals to the inner land of the Union and Xinjiang, but this should be done by the Soviet local governments stage by stage.

- the Soviet Union provides the Chinese nationals with certain duration of time, which ranges from two weeks to one month, to conclude personal issues.

- the Soviet Union will only relocate the Chinese with capability and willingness to work in the Soviet Union to her inland and she will provide convenience for the rest of the Chinese to return to China via Xinjiang.

- the Soviet Union will assist the Chinese to dispose of their real estates, either for sale or for trusteeship. If there is no available trustee, the Chinese consulates can serve as the trustee, only if not massive real estates are under the trusteeship of the consulates. City authorities will send specialized official to make the assistance.

- Foreign affairs sections of city authorities should create a name list of Chinese for the relocation as is defined by Article 3, a copy of the list to state the time for relocation. The two documents should be submitted via diplomatic representations to the Chinese Consulate in Vladivostok, Khabarovsk and Prague for backup.

- the Soviet Union allows the Soviet wives of the Chinese to go to China.

- the Soviet Union principally agrees to release Chinese under detention, unless the person commit severe crimes.

On 10th June 1938, the Politburo passed the resolution on Relocation of the Chinese in Far East, stopping compelling Chinese. The Chinese were allowed to move to Xinjiang. If the Chinese person was unwilling to move to Xinjiang, he/she would be relocated to a Soviet territory except for the frontier closed and forted area in Far East. If the Chinese person was unwilling to move to Xinjiang but he has no property in Far East, he/she should be relocated to Kazakhstan. If the Chinese was accused of espionage and sabotage, he/she should not be released.[53]

統計

[edit]一般来说,遭受肃反或受肃反影响的华人可以分为四大类:一、就地释放;二、返回新疆;三、流放哈萨克或其他远东以外的苏联地区;四、处决与进古拉格。另有若干华人在拘捕或审讯过程中死亡,具体数量无法得知。

| 处分方法 | 处分人数 |

| 就地释放 | 3,794人 |

| 返回新疆 | 11,412人 |

| 流放至远东以外的苏联地区 | 5,763人 |

| 拘禁或处决 | 9,830人 |

| 总受害人数 | 30,899人

直接因肃反受难者为27,558人 |

远东本地释放

[edit]| 释放方法 | 释放人数 |

| 就地释放 | 2,853人 |

| 迁移至库尔—乌尔米地区释放 | 941人 |

| 总释放人数 | 3,794人 |

1938年6月,内务人民委员部远东边疆区内务管理局按照联共(布)中央的指示,重新查看部分侦讯文件后,从羁押中释放2,853人[54]。当中艾戈尔舍尔德(Эгершельд)车站第五列车的941人开往哈巴罗夫斯克边疆区的库尔—乌尔米地区[註 1],这些人在抵达当地后亦获赦[55]。

返回新疆

[edit]| 回疆出发日期 | 返回人数 |

| 6月13日至7月8日 | 释囚6,189人 |

| 7月11至7月14日 | 民众3,341人[註 2] |

| 10月11至10月12日 | 释囚1,882人 |

| 总返回人数 | 11,412人 |

由于华侨进入新疆需要中国使领机构的签证,根据中国驻海参崴、伯力、布拉哥三所总领馆上报的1938年移侨新疆签证统计数字:“海参崴总领馆为8,025名华侨发放入境新疆签证,伯力领馆为3,004名,布拉哥领馆为2.714名[56]”。由于当时东北已为日本傀儡国满州国所据,而蒙古人民共和国内又尚未有铁路连接中俄两国,因此被释华人经西伯利亚铁路向西进发,抵新西伯利亚后转乘南下列车经阿勒泰地区抵新疆。1938年6月13日至7月8日,在海参崴的艾戈尔舍尔德(Эгершельд)车站,7,130名华人分乘5列火车被强行迁走,前四列列车6189人(分别为1379人、1637人、1613人和1560人)遣返新疆。其馀941人坐第五列车北上。第二次出发在7月11至7月14日,共3,341名普通平民先后乘车返回新疆。第三次出发在10月11至10月12日,释放罪行较轻的囚犯1,882人。共11,412人返回新疆。其中滨海州6189名、乌苏里斯克州1665名、布拉哥1815名、伯力1743名[57]。

流放至远东以外的苏联地区

[edit]| 流放地点 | 流放人数 |

| 哈萨克斯坦 | 5,116人 |

| 乌兹别克斯坦 | 451人 |

| 其他地区 | 196人 |

| 总流放人数 | 5,763人 |

依据苏联统计机关的人口普查结果,在1926—1937年这段时间内,中亚地区中国人数量极少,可是在[[:ru:Перепись населения СССР (1939)|1939年苏联人口普查

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

别里科夫等was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b 刘涛,卜君哲 (2010). "俄罗斯远东开发与华人华侨(1860-1941)". 延边大学学报: 社会科学版 (in 中文).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ 安妮·阿普尔鲍姆作,戴大洪译 (2013). 古拉格:一部历史 (in 中文). 北京: 新星出版社. p. 134.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b c Бугай Н.Ф. (2018). И. Сталин - Мао Цзэдун: судьбы китайцев в СССР – России (in Russian). Москва: Филин. ISBN 978-5-9216-0566-4.

- ^ Чернолуцкая Е. Н. (2014年). "Принудительные миграции на советском Дальнем Востоке в 1920-1950-е гг". Специальность ВАК РФ (in Russian) (7): 262.

- ^ 尹广明 (2016年). "苏联处置远东华人问题的历史考察(1937—1938)". 近代史研究 (in 中文) (2).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Списки жертв" (in Russian). Retrieved 2019/11/30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Бугай Н. Ф. (2015). "Политические репрессии в СССР граждан Монголии и Китая на территории БМ АССР". Научные журналы БГУ (in Russian) (1): 72–77.

- ^ Жиромская Б. В. ,Поляков Ю. А. (1996). "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1937 года" (PDF) (in Russian). НАУКА. Retrieved 2019/12/2.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:3was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c 谢清明 (2014年). "十月革命前后的旅俄华工及苏俄相关政策研究". 江汉学术 (in 中文) (2).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "报载苏俄虐待华侨乞饬严重交涉由" (in 中文). 山东昌邑县商会. 1923年03月. Retrieved 2019/11/30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ 谢清明 (2014年). "十月革命前后的旅俄华工及苏俄相关政策研究". 江汉学术 (in 中文) (2): 115–116.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ 谢清明 (2015年). "抗战初期的苏联远东华侨问题(1937-1938)". 西伯利亚研究 (in 中文) (1).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ K·A·特卡乔娃,林凤江 (1995年). "俄罗斯远东移民史初探". 西伯利亚研究 (in 中文) (1).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Залесская О. В. (2009). "Китайские мигранты на Дальнем Востоке России : 1858-1938 гг". Археологии и этнографии народов Дальнего Востока ДВО РАН (in Russian) (1). Благовещенск.

- ^ 尹广明 (2016年). "苏联处置远东华人问题的历史考察(1937—1938)". 近代史研究 (in 中文) (2): 41.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Шишлянников Р. Рясенцев А. Мевзос Г. (1929). Дальневосточный край в цифрах (in Russian). Хабаровский край: страницы истории. p. 196.

- ^ Ларин А.Г. (2009). Китайские мигранты в России. История и современность (in Russian). Восточная книга. p. 124.

- ^ a b c d 卜君哲 (2003年). "近代俄罗斯西伯利亚及远东地区华侨华人社会研究(1860—1931年)" (PDF). 东北师范大学 (in 中文).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Маленкова А. А. (2014). "Политика советских властей в отношении китайской диаспоры на Дальнем Востоке СССР в 1920— 1930 -Е ГГ". Проблемы Дальнего Востока (in Russian) (4): 129.

- ^ "海参威华侨被拘禁" (in 中文). 申报. 1929年7月24日. pp. 第六版. Retrieved 2019/12/4.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "威部在狱华侨受虐待" (in 中文). 申报. 1929年8月12日. pp. 第七版. Retrieved 2019/12/4.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "伯力华侨备受虐待" (in 中文). 申报. 1929年8月26日. pp. 第八版. Retrieved 2019/12/4.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "威埠华侨复遭逮捕" (in 中文). 申报. 1929年9月17日. pp. 第四版. Retrieved 2019/12/4.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "苏俄大捕华侨" (in 中文). 申报. 1929年9月15日. pp. 第八版. Retrieved 2019/12/4.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "威部在狱华侨受虐待" (in 中文). 申报. 1929年9月21日. pp. 第四版. Retrieved 2019/12/4.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ СНК СССР и ЦК ВКП(б) (1937年8月21日). "О выселении корейского населения пограничных районов Дальневосточного края" (in Russian). ЦК ВКП(б). Retrieved 2019/11/30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Ежов Н. И. (1937年10月23日). "Оперативный приказ НКВД СССР № 00693 «Об операции по репрессированию перебежчиков — нарушителей госграницы СССР" (in Russian). НКВД. Retrieved 2019/12/01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "苏联为巩固远东防务及发展经济向西伯利亚远东一带移民" (in 中文). 驻赤塔领事商务组. 1937年11月10日. Retrieved 2019/12/05.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Ежов Н. И. (1937年12月22日). "Указание наркома НКВД Н.И. Ежова начальнику УНКВД по ДВК Г.С. Люшкову об аресте китайцев" (in Russian). НКВД. Retrieved 2019/11/30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Ежов Н. И. (1937年12月23日). "Указание наркома НКВД Н.И. Ежова начальнику УНКВД по ДВК Г.С. Люшкову об аресте китайцев" (in Russian). ЦА ФСБ. Retrieved 2019/11/30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ 尹广明 (2016年). "苏联处置远东华人问题的历史考察(1937—1938)". 近代史研究 (in 中文) (2): 43.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b c d Хлевнюк О.В. (1992). 1937-й: Сталин, НКВД и советское общество (in Russian). Москва: Республика.

- ^ 李朔根 (2017年8月29日). "驱逐、被迫移徙和定居中亚的进程" (PDF) (in Korean). 国史馆論丛 第103辑. Retrieved 2019/12/05.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Земсков, В. Н. (1990). "Спецпоселенцы" (PDF) (in Russian). МВД СССР. Retrieved 2019/12/05.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "俄远东挖掘政治大清洗牺牲者尸骨 发现华人遗骸" (in 中文). 新华网. 2010年6月8日. Retrieved 2019/12/05.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Чернолуцкая Е. Н. (2014年). "Принудительные миграции на советском Дальнем Востоке в 1920-1950-е гг". Специальность ВАК РФ (in Russian) (7): 259.

- ^ a b 尹广明 (2016年). "苏联处置远东华人问题的历史考察(1937—1938)". 近代史研究 (in 中文) (2): 44.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "俄远东一带有大批华侨被捕事" (in 中文). 中华民国驻苏联大使馆(莫斯科总领馆). 1938年1月11日. Retrieved 2019/11/30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "关于苏联大捕华侨案" (in 中文). 驻海参崴总领事馆. 1938年1月13日. Retrieved 2019/11/30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ 周成芳、耿明、马兴华等编纂 (民国27年2月6日). "苏俄虐待华侨 民国27年2月6日 中央日报头版" (in 中文). 中央日报. p. 1. Retrieved 2019/12/1.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "苏联逮捕华侨附移新侨民卷(1937-08~1938-07)" (in 中文). 中华民国驻海参崴总领馆. 1937年-1938年. p. 176. Retrieved 2019/11/30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ 周成芳、耿明、马兴华等编纂 (民国27年2月19日). "赤俄虐待华侨 民国27年2月19日 中央日报次版" (in 中文). 中央日报. p. 2. Retrieved 2019/12/1.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "苏联虐俄华侨之可愤 民国27年2月21日 工商日报第四版" (in 中文). 工商日报. 民国27年2月21日. p. 4. Retrieved 2019/12/1.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "华侨被捕" (in 中文). 中华民国驻伯力总领馆. 1937年2月22日. Retrieved 2019/11/30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "俄境远东逮捕华侨事" (in 中文). 驻伯利总领馆;驻海参崴总领馆. 1937年3月2日. Retrieved 2019/11/30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "电俄境远东逮捕华侨事" (in 中文). 驻海参崴总领馆;驻伯利总领馆. 1937年3月29日. Retrieved 2019/11/30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ 谢清明 (2015年). "抗战初期的苏联远东华侨问题(1937-1938)". 西伯利亚研究 (in 中文) (1): 87.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "海参崴总领馆电外交部" (in 中文). 驻海参崴总领馆. 1937年5月7日. Retrieved 2019/12/05.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "与苏外部谈判移侨问题" (in 中文). 中华民国驻苏联大使馆,外交部. 1938年4月16日. Retrieved 2019/11/30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ 尹广明 (2016年). "苏联处置远东华人问题的历史考察(1937—1938)". 近代史研究 (in 中文) (2): 50.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Сталин И. В. (1937年6月10日). "АП РФ,Ф. 3. Оп. 58. Д. 139. Л. 106 - 107" (in Russian). ЦК ВКП(б). Retrieved 2019/11/30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Чернолуцкая Е. Н. (2014年). "Принудительные миграции на советском Дальнем Востоке в 1920-1950-е гг". Специальность ВАК РФ (in Russian) (7): 262.

- ^ Фартусов Д. Б. (2015). "Принудительные миграции на советском Дальнем Востоке в 1920-1950-е гг". Гуманитарные исследования Внутренней Азии, БГУ (in Russian) (1).

- ^ 《海参崴总领馆电外交部》(1939年1月26日),国民政府外交部档案,04/02/009/01/142

- ^ Фартусов Д. Б. (2015). "Принудительные миграции на советском Дальнем Востоке в 1920-1950-е гг". Гуманитарные исследования Внутренней Азии, БГУ (in Russian) (1).

Cite error: There are <ref group=註> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=註}} template (see the help page).