Vastu shastra

Vastu shastra (vāstu śāstra) is a traditional Hindu system of architecture[3] which literally translates to "science of architecture."[4] These are texts found on the Indian subcontinent that describe principles of design, layout, measurements, ground preparation, space arrangement and spatial geometry.[5][6] Vastu Shastras incorporate traditional Hindu and in some cases Buddhist beliefs.[7] The designs are intended to integrate architecture with nature, the relative functions of various parts of the structure, and ancient beliefs utilizing geometric patterns (yantra), symmetry and directional alignments.[8][9]

Vastu Shastra are the textual part of Vastu Vidya, the latter being the broader knowledge about architecture and design theories from ancient India.[10] Vastu Vidya knowledge is a collection of ideas and concepts, with or without the support of layout diagrams, that are not rigid. Rather, these ideas and concepts are models for the organization of space and form within a building or collection of buildings, based on their functions in relation to each other, their usage and to the overall fabric of the Vastu.[10] Ancient Vastu Shastra principles include those for the design of Mandir (Hindu temples),[11] and the principles for the design and layout of houses, towns, cities, gardens, roads, water works, shops and other public areas.[6][12][13]

Terminology

The Sanskrit word vastu means a dwelling or house with a corresponding plot of land.[14] The vrddhi, vāstu, takes the meaning of "the site or foundation of a house, site, ground, building or dwelling-place, habitation, homestead, house". The underlying root is vas "to dwell, live, stay, reside".[15] The term shastra may loosely be translated as "doctrine, teaching".

Vastu-Sastras (literally, science of dwelling) are ancient Sanskrit manuals of architecture. These contain Vastu-Vidya (literally, knowledge of dwelling).[16]

History

Historians such as James Fergusson, Alexander Cunningham and Dr. Havell have suggested that Vastu Shastra developed between 6000 BCE and 3000 BCE, adding that the archaeological sites of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro stand on the principles of Vastu Shashtra.[17][verification needed]

Description

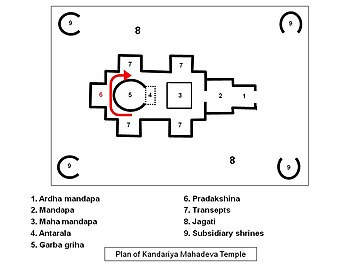

There exist many Vastu-Sastras on the art of building houses, temples, towns and cities. One such Vastu Sastra is by Thakkura Pheru, describing where and how temples should be built.[8][19] By 6th century AD, Sanskrit manuals for constructing palatial temples were in circulation in India.[20] Vastu-Sastra manuals included chapters on home construction, town planning,[16] and how efficient villages, towns and kingdoms integrated temples, water bodies and gardens within them to achieve harmony with nature.[12][13] While it is unclear, states Barnett,[21] as to whether these temple and town planning texts were theoretical studies and if or when they were properly implemented in practice, the manuals suggest that town planning and Hindu temples were conceived as ideals of art and integral part of Hindu social and spiritual life.[16]

The Silpa Prakasa of Odisha, authored by Ramacandra Bhattaraka Kaulacara sometime in ninth or tenth century CE, is another Vastu Sastra.[22] Silpa Prakasa describes the geometric principles in every aspect of the temple and symbolism such as 16 emotions of human beings carved as 16 types of female figures. These styles were perfected in Hindu temples prevalent in eastern states of India. Other ancient texts found expand these architectural principles, suggesting that different parts of India developed, invented and added their own interpretations. For example, in Saurastra tradition of temple building found in western states of India, the feminine form, expressions and emotions are depicted in 32 types of Nataka-stri compared to 16 types described in Silpa Prakasa.[22] Silpa Prakasa provides brief introduction to 12 types of Hindu temples. Other texts, such as Pancaratra Prasada Prasadhana compiled by Daniel Smith[23] and Silpa Ratnakara compiled by Narmada Sankara[24] provide a more extensive list of Hindu temple types.

Ancient Sanskrit manuals for temple construction discovered in Rajasthan, in northwestern region of India, include Sutradhara Mandana’s Prasadamandana (literally, manual for planning and building a temple) with chapters on town building.[25] Manasara shilpa and Mayamata, texts of South Indian origin, estimated to be in circulation by 5th to 7th century AD, is a guidebook on South Indian Vastu design and construction.[8][26] Isanasivagurudeva paddhati is another Sanskrit text from the 9th century describing the art of building in India in south and central India.[8][27] In north India, Brihat-samhita by Varāhamihira is the widely cited ancient Sanskrit manual from 6th century describing the design and construction of Nagara style of Hindu temples.[18][28][29]

These ancient Vastu Sastras, often discuss and describe the principles of Hindu temple design, but do not limit themselves to the design of a Hindu temple.[30] They describe the temple as a holistic part of its community, and lay out various principles and a diversity of alternate designs for home, village and city layout along with the temple, gardens, water bodies and nature.[13][31]

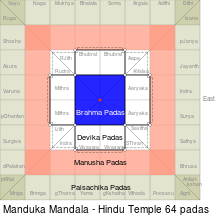

Mandala types and properties

The central area in all mandala is the Brahmasthana. Mandala "circle-circumference" or "completion", is a concentric diagram having spiritual and ritual significance in both Hinduism and Buddhism. The space occupied by it varies in different mandala – in Pitha (9) and Upapitha (25) it occupies one square module, in Mahaapitha (16), Ugrapitha (36) and Manduka (64), four square modules and in Sthandila (49) and Paramasaayika (81), nine square modules.[32] The Pitha is an amplified Prithvimandala in which, according to some texts, the central space is occupied by earth. The Sthandila mandala is used in a concentric manner.[32]

The most important mandala is the Manduka/ Chandita Mandala of 64 squares and the Paramasaayika Mandala of 81 squares. The normal position of the Vastu Purusha (head in the northeast, legs in the southwest) is as depicted in the Paramasaayika Mandala. However, in the Manduka Mandala the Vastu Purusha is depicted with the head facing east and the feet facing west. [citation needed]

It is believed that every piece of a land or a building has a soul of its own and that soul is known as Vastu Purusha.[33]

A site of any shape can be divided using the Pada Vinyasa. Sites are known by the number of squares. They range from 1x1 to 32x32 (1024) square sites. Examples of mandalas with the corresponding names of sites include:[8]

- Sakala (1 square) corresponds to Eka-pada (single divided site)

- Pechaka (4 squares) corresponds to Dwi-pada (two divided site)

- Pitha (9 squares) corresponds to Tri-pada (three divided site)

- Mahaapitha (16 squares) corresponds to Chatush-pada (four divided site)

- Upapitha (25 squares) corresponds to Pancha-pada (five divided site)

- Ugrapitha (36 squares) corresponds to Shashtha-pada (six divided site)

- Sthandila (49 squares) corresponds to sapta-pada (seven divided site)

- Manduka/ Chandita (64 square) corresponds to Ashta-pada (eight divided site))

- Paramasaayika (81 squares)

- Paramasaayika (81 squares) corresponds to Nava-pada (nine divided site)

- Aasana (100 squares) corresponds to Dasa-pada (ten divided site)

- bhadrmahasan (196 squares) corresponds to chodah -pada (14 divided sites)

Modern adaptations and usage

Vastu sastra represents a body of ancient concepts and knowledge to many modern architects, a guideline but not a rigid code.[9][35] The square-grid mandala is viewed as a model of organization, not as a ground plan. The ancient Vastu sastra texts describe functional relations and adaptable alternate layouts for various rooms or buildings and utilities, but do not mandate a set compulsory architecture. Sachdev and Tillotson state that the mandala is a guideline, and employing the mandala concept of Vastu sastra does not mean every room or building has to be square.[9] The basic theme is around core elements of central space, peripheral zones, direction with respect to sunlight, and relative functions of the spaces.[9][35]

The pink city Jaipur in Rajasthan was master planned by Rajput king Jai Singh and built by 1727 CE, in part around Vastu Shilpa Sastra principles.[9][36][36] Similarly, modern era projects such as the architect Charles Correa's designed Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya in Ahmedabad, Vidhan Bhavan in Bhopal,[37] and Jawahar Kala Kendra in Jaipur, adapt and apply concepts from the Vastu Shastra Vidya.[9][35] In the design of Chandigarh city, Le Corbusier incorporated modern architecture theories with those of Vastu Shastra.[38][39][40]

During the colonial rule period of India, town planning officials of the British Raj did not consider Vastu Vidya, but largely grafted Islamic Mughal era motifs and designs such as domes and arches onto Victorian-era style buildings without overall relationship layout.[41][42] This movement, later known as the Indo-Saracenic style, is found in chaotically laid out, but externally grand structures in the form of currently used major railway stations, harbors, tax collection buildings, and other colonial offices in South Asia.[41]

Vastu sastra vidya was ignored, during colonial era construction, for several reasons. These texts were viewed by 19th and early 20th century architects as archaic, the literature was inaccessible being in an ancient language not spoken or read by the architects, and the ancient texts assumed space to be readily available.[35][41] In contrast, public projects in the colonial era were forced into crowded spaces and local layout constraints, and the ancient Vastu sastra were viewed with prejudice as superstitious and rigid about a square grid or traditional materials of construction.[41] Sachdev and Tillotson state that these prejudices were flawed, as a scholarly and complete reading of the Vastu sastra literature amply suggests the architect is free to adapt the ideas to new materials of construction, local layout constraints and into a non-square space.[41][43] The design and completion of a new city of Jaipur in early 1700s based on Vastu sastra texts, well before any colonial era public projects, was one of many proofs.[41][43] Other examples include modern public projects designed by Charles Correa such as Jawahar Kala Kendra in Jaipur, and Gandhi Ashram in Ahmedabad.[9][34] Vastu Shastra remedies have also been applied by Khushdeep Bansal in 1997 to the Parliament complex of India, when he contented that the library being built next to the building is responsible for political instability in the country.[44]

Klaus-Peter Gast states that the principles of Vastu Shastras is witnessing a major revival and wide usage in the planning and design of individual homes, residential complexes, commercial and industrial campuses, and major public projects in India, along with the use of ancient iconography and mythological art work incorporated into the Vastu vidya architectures.[34][45]

Vastu and superstition

The use of Vastu shastra and Vastu consultants in modern home and public projects is controversial.[43] Some architects, particularly during India's colonial era, considered it arcane and superstitious.[35][41] Other architects state that critics have not read the texts and that most of the text is about flexible design guidelines for space, sunlight, flow and function.[35][45]

Vastu Shastra is considered as pseudoscience by rationalists like Narendra Nayak of Federation of Indian Rationalist Associations.[46] Scientist and astronomer Jayant Narlikar considers Vastu Shastra as pseudoscience and writes that Vastu does not have any "logical connection" to the environment.[4] One of the examples cited by Narlikar arguing the absence of logical connection is the Vastu rule, "sites shaped like a triangle ... will lead to government harassment, ... parallelogram can lead to quarrels in the family." Narlikar notes that sometimes the building plans are changed and what has already been built is demolished to accommodate for Vastu rules.[4] Regarding superstitious beliefs in Vastu, Science writer Meera Nanda cites the case of N.T.Rama Rao, the ex-chief minister of Andhra Pradesh, who sought the help of Vastu consultants for his political problems. Rama Rao was advised that his problems would be solved if he entered his office from an east facing gate. Accordingly, a slum on the east facing side of his office was ordered to be demolished, to make way for his car's entrance.[47][48] The knowledge of Vastu consultants is questioned by Pramod Kumar, "Ask the Vaastu folks if they know civil engineering or architecture or the local government rules on construction or minimum standards of construction to advise people on buildings. They will get into a barrage of "ancient" texts and "science" that smack of the pseudo-science of astrology. Ask them where they were before the construction boom and if they will go to slum tenements to advise people or advise on low-cost community-housing—you draw a blank."[49]

Vastu Shastras — Sanskrit treatises on architecture

Of the numerous Sanskrit treatises mentioned in ancient Indian literature, some have been translated in English. Many Agamas, Puranas and Hindu scriptures include chapters on architecture of temples, homes, villages, towns, fortifications, streets, shop layout, public wells, public bathing, public halls, gardens, river fronts among other things.[6] In some cases, the manuscripts are partially lost, some are available only in Tibetan, Nepalese or South Indian languages, while in others original Sanskrit manuscripts are available in different parts of India. Some treatises, or books with chapters on Vaastu Shastra include:[6]

See also

- Aranmula Kottaram

- Feng Shui

- Kanippayyur Shankaran Namboodiripad

- Maharishi Vastu Architecture

- Shilpa Shastras

- Tiang Seri

References

- ^ "Angkor Temple Guide". Angkor Temple Guide. 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ R Arya, Vaastu: The Indian Art of Placement, ISBN 978-0892818853

- ^ Quack, Johannes (2012). Disenchanting India: Organized Rationalism and Criticism of Religion in India. Oxford University Press. p. 119. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ a b c Narlikar, Jayant V. (2009). "Astronomy, pseudoscience and rational thinking". In Percy, John; Pasachoff, Jay (eds.). Teaching and Learning Astronomy: Effective Strategies for Educators Worldwide. Cambridge University Press. p. 165.

- ^ "GOLDEN PRINCIPLES OF VASTU SHASTRA Vastukarta". www.vastukarta.com. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d Acharya P.K. (1946), An Encyclopedia of Hindu Architecture, Oxford University Press

- ^ Kumar, Vijaya (2002). Vastushastra. New Dawn/Sterling. p. 5. ISBN 978-81-207-2199-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Stella Kramrisch (1976), The Hindu Temple Volume 1 & 2, ISBN 81-208-0223-3

- ^ a b c d e f g h Vibhuti Sachdev, Giles Tillotson (2004). Building Jaipur: The Making of an Indian City. pp. 155–160. ISBN 978-1861891372.

- ^ a b Vibhuti Sachdev, Giles Tillotson (2004). Building Jaipur: The Making of an Indian City. p. 147. ISBN 978-1861891372.

- ^ George Michell (1988), The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226532301, pp 21-22

- ^ a b GD Vasudev (2001), Vastu, Motilal Banarsidas, ISBN 81-208-1605-6, pp 74-92

- ^ a b c Sherri Silverman (2007), Vastu: Transcendental Home Design in Harmony with Nature, Gibbs Smith, Utah, ISBN 978-1423601326

- ^ Gautum, Jagdish (2006). Latest Vastu Shastra (Some Secrets). Abhinav Publications. p. 17. ISBN 978-81-7017-449-3.

- ^ Monier-Williams (1899).

- ^ a b c BB Dutt (1925), Town planning in Ancient India at Google Books, ISBN 978-81-8205-487-5; See critical review by LD Barnett, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol 4, Issue 2, June 1926, pp 391

- ^ Vāstu, Astrology, and Architecture: Papers Presented at the First All India Symposium on Vāstu. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. 1998. p. 74.

- ^ a b Meister, Michael W. (1983). "Geometry and Measure in Indian Temple Plans: Rectangular Temples". Artibus Asiae. 44 (4): 266–296. doi:10.2307/3249613. JSTOR 3249613.

- ^ Jack Hebner (2010), Architecture of the Vastu Sastra - According to Sacred Science, in Science of the Sacred (Editor: David Osborn), ISBN 978-0557277247, pp 85-92; N Lahiri (1996), Archaeological landscapes and textual images: a study of the sacred geography of late medieval Ballabgarh, World Archaeology, 28(2), pp 244-264

- ^ Susan Lewandowski (1984), Buildings and Society: Essays on the Social Development of the Built Environment, edited by Anthony D. King, Routledge, ISBN 978-0710202345, Chapter 4

- ^ LD Barnett, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol 4, Issue 2, June 1926, pp 391

- ^ a b Alice Boner and Sadāśiva Rath Śarmā (1966), Silpa Prakasa Medieval Orissan Sanskrit Text on Temple Architecture at Google Books, E.J. Brill (Netherlands)

- ^ H. Daniel Smith (1963), Ed. Pāncarātra prasāda prasādhapam, A Pancaratra Text on Temple-Building, Syracuse: University of Rochester, OCLC 68138877

- ^ Mahanti and Mahanty (1995 Reprint), Śilpa Ratnākara, Orissa Akademi, OCLC 42718271

- ^ Amita Sinha (1998), Design of Settlements in the Vaastu Shastras, Journal of Cultural Geography, 17(2), pp 27-41, doi:10.1080/08873639809478319

- ^ Tillotson, G. H. R. (1997). Svastika Mansion: A Silpa-Sastra in the 1930s. South Asian Studies, 13(1), pp 87-97

- ^ Ganapati Sastri (1920), Īśānaśivagurudeva paddhati, Trivandrum Sanskrit Series, OCLC 71801033

- ^ Heather Elgood (2000), Hinduism and the religious arts, ISBN 978-0304707393, Bloomsbury Academic, pp 121-125

- ^ H Kern (1865), The Brhat Sanhita of Varaha-mihara, The Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta

- ^ S Bafna, On the Idea of the Mandala as a Governing Device in Indian Architectural Tradition, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 59, No. 1 (Mar., 2000), pp. 26-49

- ^ Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, Vol 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0222-3

- ^ a b Vibhuti Chakrabarti (2013). Indian Architectural Theory: Contemporary Uses of Vastu Vidya. Routledge. pp. 86–99. ISBN 978-0700711130.

- ^ http://www.rockingbaba.com/blog/index.php/2015/07/06/vastu-for-beginners-blog-3/

- ^ a b c Klaus-Peter Gast (2011). Modern Traditions: Contemporary Architecture in India. Birkhäuser Architecture. p. 11. ISBN 978-3764377540.

- ^ a b c d e f V Chakrabarti (2013). Indian Architectural Theory: Contemporary Uses of Vastu Vidya. Routledge. pp. 86–92. ISBN 978-0700711130.

- ^ a b Jantar Mantar & Jaipur - Section II National University of Singapore, pp. 17-22

- ^ Irena Murray (2011). Charles Correa: India's Greatest Architect. RIBA Publishing. ISBN 978-1859465172.

- ^ Gerald Steyn (2011). "Le Corbusier's research-based design approaches" (PDF). SAJAH. 26 (3). Tshwane University of Technology: 45–56.

- ^ H Saini (1996). Vaastu ordains a full flowering for Chandigarh. The Tribune.

- ^ Reena Patra (2009). "Vaastu Shastra: Towards Sustainable Development". Sustainable Development. 17. Wiley InterScience: 244–256.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vibhuti Sachdev, Giles Tillotson (2004). Building Jaipur: The Making of an Indian City. pp. 149–157. ISBN 978-1861891372.

- ^ Anthony D'Costa. A New India?: Critical Reflections in the Long Twentieth Century. pp. 165–168. ISBN 978-0857285041.

- ^ a b c V Chakrabarti (2013). Indian Architectural Theory: Contemporary Uses of Vastu Vidya. Routledge. pp. 86–99. ISBN 978-0700711130.

- ^ "'Harmonising' homes, hearts". Hindustan Times. 9 June 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ a b Stephen Marshall (2011). Urban Coding and Planning. Routledge. pp. 83–103. ISBN 978-0415441261.

- ^ Quack, Johannes (2012). Disenchanting India: Organized Rationalism and Criticism of Religion in India. Oxford University Press. p. 170. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ Sokal, Alan (2008). Beyond the Hoax: Science, Philosophy and Culture. Oxford University Press. pp. 306–307.

- ^ Nanda, Meera (1997). "The Science Wars in India". DISSENT. 44 (1).

- ^ Kumar, Pramod (14 May 2013). "Akshaya Tritiya and the great Indian superstition industry". Firstpost. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

Further reading

- Acharya P.K. (1946), An Encyclopedia of Hindu Architecture, Oxford University Press - Terminology of Ancient Architecture

- Acharya P.K. (1946), Bibliography of Ancient Sanskrit Treatises on Architecture and Arts, in An Encyclopedia of Hindu Architecture, Oxford University Press - pages 615-659

- B.B. Dutt (1925), Town Planning in Ancient India at Google Books

- V. Chakraborty, Indian Architectural Theory: Contemporary Uses of Vastu Vidya at Google Books

- Arya, Rohit Vaastu: the Indian art of placement : design and decorate homes to reflect eternal spiritual principles Inner Traditions / Bear & Company, 2000, ISBN 0-89281-885-9.

- Important Concepts of Vasthu Shasthra Traditional Indian Architecture

- Vastu: Transcendental Home Design in Harmony with Nature, Sherri Silverman

- Prabhu, Balagopal,T.S and Achyuthan,A, "A text Book of Vastuvidya", Vastuvidyapratisthanam, Kozhikode, New Edition, 2011.

- Prabhu, Balagopal,T.S and Achyuthan,A, "Design in Vastuvidya", Vastuvidyapratisthanam, Kozhiko

- Prabhu, Balagopal,T.S, "Vastuvidyadarsanam",(Malayalam) Vastuvidyapratisthanam, Kozhikode.

- Prabhu, Balagopal,T.S and Achyuthan,A, "Manusyalaya candrika- An Engineering Commentary", Vastuvidyapratisthanam, Kozhikode, New Edition, 2011.

- Vastu-Silpa Kosha, Encyclopedia of Hindu Temple architecture and Vastu/S.K.Ramachandara Rao, Delhi, Devine Books, (Lala Murari Lal Chharia Oriental series) ISBN 978-93-81218-51-8 (Set)

- D. N. Shukla, Vastu-Sastra: Hindu Science of Architecture, Munshiram Manoharial Publishers, 1993, ISBN 978-81-215-0611-3.

- B. B. Puri, Applied vastu shastra vaibhavam in modern architecture, Vastu Gyan Publication, 1997, ISBN 978-81-900614-1-4.

- Vibhuti Chakrabarti, Indian Architectural Theory: Contemporary Uses of Vastu Vidya Routledge, 1998, ISBN 978-0-7007-1113-0.

- Dr. Puneet Chwala, Vaastu Passage To Fortune amazon.in, 2015,ISBN 8192948218

ISBN 978-8192948218.