Visby Cathedral

| Visby Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Visby Sankta Maria domkyrka | |

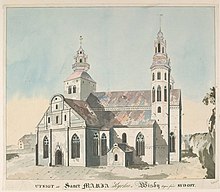

View from the northeast | |

| |

| 57°38′30″N 18°17′52″E / 57.64167°N 18.29778°E | |

| Location | Visby |

| Country | Sweden |

| Denomination | Church of Sweden |

| Previous denomination | Catholic Church Church of Denmark |

| Website | Official site (in Swedish) |

| History | |

| Dedication | Blessed Virgin Mary |

| Consecrated | 27 July 1225 (cathedral since 1572) |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Architect(s) | Axel Haig (1899–1903) Jerk Alton (1979–1985) |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 55.5 m (182 ft)[1] |

| Width | 24.7 m (81 ft) (at its widest point)[1] |

| Height | 58 m (190 ft) (tallest point of the west tower)[1] |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Diocese of Visby |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Thomas Petersson (bishop) |

Visby Cathedral (Swedish: Visby domkyrka), formally Visby Saint Mary's Cathedral (Visby Sankta Maria domkyrka), is a cathedral within the Church of Sweden, seat of the Bishop of Visby. It lies in the centre of Visby, the main town on the Swedish island Gotland. It was built as the church of the German traders in the city during the 13th century. The first church was probably a wooden church, which was later replaced by a stone building. Originally built as a basilica, it was successively expanded and rebuilt during the Middle Ages. At the end of this period it had been transformed to a hall church, which it still is. In 1361, Gotland and the church became part of Denmark. Following the Reformation, it was the only medieval church in the city left in use, and in 1572 raised to the status of cathedral. Since 1645 Gotland and the cathedral have been part of Sweden. A major renovation was carried out in 1899–1903 under the guidance of architect Axel Haig.

The cathedral consists of a nave with two aisles, a square chancel, a square western tower and two smaller, octagonal towers to the east. Stylistically, it is related to medieval German models, particularly from Westphalia and the Rhineland, but indirect influences from France are also discernible in the Gothic architecture of the cathedral. In turn, its architecture influenced both local church building on Gotland and certain elements in the cathedrals of Linköping and Uppsala on mainland Sweden. It contains furnishings from several centuries; its main altarpiece is a Gothic revival piece from 1905.

History

[edit]Foundation, construction and development during the Middle Ages

[edit]Visby Cathedral was not originally built as a cathedral, but as a church for the German traders who visited Visby during the 13th century.[2] The city was an important port of the powerful, German-dominated Hanseatic League, and the church was one of the most important churches of the city. At the end of the Middle Ages Saint Mary's Church was the richest church in Visby by far,[3] and it was the second-largest church of the city.[4] Being a church for itinerant traders, it originally lacked a territorial congregation and was not subjected to any bishop or lord. Instead, it would be used by the traders whenever they were in Visby, and they brought along their own clergy. At other times the church was simply unused and stood empty.[2] Eventually several of the traders settled permanently in Visby, and formed a territorial congregation subjected, like all of Gotland, to the Bishop of Linköping.[5] Henceforth Saint Mary's Church was used both by the German congregation of Visby, and by the visiting German traders who continued to bring their own priests.[2]

The first church building was probably wooden, but no traces remain of this building.[5] Construction of the current, stone building started during the second half of the 12th century.[6] Funding was supplied through a levy which all visiting German traders had to pay.[7] It was consecrated by Bishop Bengt of Linköping on 27 July 1225.[5] This first stone church was a basilica in Romanesque style. It had a nave, two aisles, a western tower and a transept. It had a square chancel and an apse-like east end. It is possible that also the transept arms had apses. Quite soon thereafter, the chancel was rebuilt into the square chancel seen today. At the same time the transept was enlarged and the two eastern, smaller towers built in the angle between the transept and the chancel. A new portal, the so-called bridal portal (Swedish: brudportalen) was constructed in the western transept where it still remains.[6]

After a short hiatus the nave was reconstructed in the middle of the 13th century. Saint Mary's Church was at the same time widened, integrating the transepts into the nave and transforming the church from a basilica to a hall church, again after models from western Germany.[8] About fifty years later, a large chapel was constructed to the south. The chapel is today simply called "the great chapel" (stora kapellet) but was in the Middle Ages dedicated to Saint Mary. New, larger tracery windows in Gothic style were also installed piecemeal during the 14th century.[8] The church roof was also raised, adding a clerestory whose windows however only provided light for a new, large attic; the exterior was thus changed to appear as that of a basilica, without altering the interior at all. These changes meant a departure from the typical hall church architecture and indicates inspiration from classical Gothic cathedral architecture.[9] The main purpose appears to have been to make the church appear more dominating from outside. The tower was heightened in 1423.[8]

Later changes

[edit]

Few changes have been made to the building since the end of the Middle Ages.[10] Since the Battle of Visby in 1361, Gotland was a Danish province, and hence was affected by the Danish Reformation. Changes in doctrine meant that the city of Visby thereafter only had need of a single church for a single congregation. The church of the German traders was chosen to serve the town, while the many other churches were left to decay; today they are preserved only as ruins on Gotland. Somewhat later, in 1572, the Diocese of Visby was established and Saint Mary's Church was promoted to the status of a cathedral.[8] In 1645, following the Treaty of Brömsebro, Gotland was ceded by Denmark to Sweden.

In 1611, a fire damaged the eastern part of the cathedral, and the spires of the east towers had to be replaced. The current wooden Baroque spires of these towers date from 1761, and the same year the gable of the great chapel was also rebuilt. The spire of the west tower is from 1746.[8] The roofs have been continually repaired since at least the 18th century, and at some point the roofs of the aisles were raised to cover the medieval clerestory.[11] The interior was renovated in 1890–93, and between 1899 and 1903 the cathedral was substantially renovated under the leadership of architect Axel Haig.[12]

Haig, who was born on Gotland but had pursued a career in the United Kingdom as an architect, produced a proposal for a renovation of the cathedral to the cathedral chapter on his own initiative. His proposal was with some minor adjustments accepted, after funding had been secured from the Swedish government. However, the funds did not include money to pay Haig, who did the work without a salary.[13] The work aimed to repair and preserve the cathedral without any major alterations, except where it was deemed necessary. The most far-reaching changes were that the 14th-century clerestory was restored, the roofs of the aisles lowered, the removal of whitewash from the facade, the construction of a new sacristy and the renovation of the gable of the great chapel in a Gothic revival style. The decoration of cathedral was also partially renewed, also in a Gothic revival style, with several new sculptures, wrought iron details and ridge turrets installed.[14] Further changes were made later during the 20th century. In 1906 electrical lighting was installed, and in 1928 a new heating system. A fire sprinkler system was installed in the west tower in 1959 and a heat system to keep downpipes from freezing in winter was installed in 1968.[15]

Another thorough renovation of the cathedral was carried out between 1979 and 1985 by architect Jerk Alton.[10] The most noticeable change made during this renovation was that the great chapel was closed off from the main room of the cathedral.[10] During the work, fragments of medieval murals were discovered in the north aisle.[16] Another renovation of the exterior and the interior was again carried out again in 2013–2015.[17]

Location and surroundings

[edit]

Visby Cathedral is located within the medieval centre of Visby, inside the city wall. Archaeologists believe that a medieval trading post for merchants from Germany was located nearby since the church was used by them; during archaeological excavations, enameled and gilded figures as well as 14th-century glassware from Syria has been unearthed nearby, indicating that goods from far away were handled in the vicinity of the church.[18] West of the cathedral lies the residence of the Bishop of Visby. Its current main building dates from 1938 to 1939 and is built in a style inspired by traditional parsonages on the countryside of Gotland. The residence complex also incorporates buildings of medieval origin.[19]

Immediately surrounding the cathedral is the irregularly shaped former cathedral cemetery. There are six entrances to the cemetery. The oldest of these is the northernmost, a crow-stepped medieval lychgate probably from the late 14th century. It retains some of its original sculpted decoration. The south entrance is Baroque in style, and contains the faded monogram of Christian IV of Denmark and the coat of arms of Jens Hög, governor of Gotland 1627–1633.[20]

Architecture

[edit]Overview

[edit]

The medieval church was stylistically closely related to German models, particularly from Westphalia and the Rhineland, which was where a large part of the German traders active on Gotland came from.[21] The so-called bridal portal, for example, is in a typically late Romanesque Rhenish style.[6] Even so, some features were local innovations. The hipped tower with its galleries, for example, had a lasting influence on church architecture on Gotland, and it inspired towers of similar design on several of the island's churches.[21] It is also probable that the development of the medieval church was influenced by developments on mainland Sweden. Some of the changes during the 14th century, e.g. the new tracery windows and the addition of a clerestory not visible from the interior, may have been inspired from the construction of Uppsala Cathedral.[9] Conversely, the architecture of the church is Visby, and in general a supply of limestone and stonemasons from Gotland to mainland Sweden, may have had an influence on elements both in Uppsala and Linköping Cathedral during the Middle Ages.[22]

Visby Cathedral has a nave with two aisles, a square chancel, a square western tower and two smaller, octagonal towers in the angle between the chancel and the nave. To the south there is a large chapel, the so-called great chapel, which projects from the south facade. A smaller chapel next to it is known as the merchants' chapel (Swedish: köpmankoret). The roof of the nave is higher than the roofs above the aisles, and supported by a clerestory which provides light to a large attic.[1] The oldest parts of the cathedral are the lower part of the western tower (up to the upper lombard band), the gables of the original transepts (incorporated in the present north and south walls), the portal from the sacristy to the church and some of the pillars and vaults.[6]

Exterior

[edit]

During the Middle Ages, the facade was probably covered with whitewash with the exception of more finely sculpted details. All whitewash was removed during the renovation by Haig.[23] The facade of the eastern part of the church, including the chancel and the two east towers, is more richly decorated than the western part of the building. A lombard band runs around the chancel, the bay with the bridal portal and the west tower, a decoration which originally ran around the entire facade.[24] The east facade has three rows of openings above the three chancel windows. These openings, which were repaired and reconstructed at the turn of the last century, originally led to the attic of the cathedral. A sculpture of Christ was also installed by Haig at the gable top; it was made in England in the 1890s.[25] The facade of the great chapel is clearly distinguished from the rest of the building, and is also the most lavishly decorated, with its large un-decorated walls, its buttresses, pinnacles and gargoyles.[26] The tabernacle frames on the buttresses next to the chapel portal are of a type quite common in continental Europe but in Sweden only known from Visby and Uppsala cathedrals.[27] Of the gargoyles, three are original and one (depicting Samson's fight with the lion) a 19th-century copy of the original. A fifth gargoyle was installed by Haig at the turn of the last century. Such gargoyles are unknown from other Swedish medieval churches, though they were copied in some churches on Gotland (e.g. Lärbro and Stånga churches).[28] Much of the upper part of the facade of the great chapel dates from Haig's restoration, including the flèche and the large sculpture of Christ and its surrounding Gothic revival framing elements.[29]

The cathedral has five portals. The tower portal is a simple Romanesque portal, slightly altered in 1821.[30] A comparatively small northwestern portal, originally medieval, has also been rebuilt several times.[31] The entrance to the sacristy dates from the restoration by Haig and its tympanum is decorated with a relief depicting Saint Nicholas. The face of Saint Nicholas bears a close resemblance to that of Bishop Knut Henning Gezelius von Schéele, who was bishop in Visby at the time.[32] The former main north portal, which today connects the sacristy with the church and thus is not visible for regular visitors, is one of the oldest preserved parts of the cathedral.[33] The aforementioned so-called bridal portal, in the south facade, is from the 13th century. Its capitals are decorated with floral ornaments, and stylistically the portal is related to Magdeburg Cathedral and the north portal of Riga Cathedral, and more generally to influences originally from Westphalia.[34] The south entrance to the great chapel is the most elaborate of the entrances. Something comparable to its unusual decoration with a succession of pinnacles as it were climbing the sides of the wimperg is only known from Strasbourg Cathedral and Cologne Cathedral; it has been assumed that it is a decorative element which arrived via French stonemasons who came to Sweden to work on Uppsala Cathedral.[35]

Interior

[edit]

The nave and two aisles form a hall church five bays long. The aisles are slightly lower than the nave, and narrower. The last bay of the nave lies a few steps higher than the rest of the church, and the square chancel a few further steps higher. The chancel itself is spatially conceived as a continuation of the nave. The walls and vaults of the church are covered with yellowish plaster, and for the rest the limestone is exposed in e.g. piers and vault ribs.[36] The vaults are supported by four pairs of piers.[37] The successive changes to the church throughout the centuries has led to an irregular and variegated interior.[36] The most south-westerly pier still support a round arch from the first building period, the only visible remnant of the basilica.[38] The capitals of the pillars are also different, ranging from capitals from the earliest building phase to capitals made during the renovation at the turn of the last century.[39] The vaults of the church are all groin vaults.[40]

The great chapel is shaped as a room of its own, consisting of three bays of equal height. It is connected with the rest of the church through a pointed arch through the west wall of the church.[41] The keystones of the vaults are decorated with sculptures depicting the Lamb of God, the head of Christ and floral motifs.[42] The capitals and corbels in the great chapel are also richly decorated with Gothic sculptures.[43]

Furnishings

[edit]

The main altarpiece of the cathedral was installed in 1905 and designed by Haig. It is in a Gothic revival style, displaying the Adoration of the Magi in the central panel, flanked by depictions of Saint Nicholas, Catherine of Vadstena, Bridget of Sweden and Saint Olaf.[44] A 16th-century altarpiece originally from the cathedral is preserved in Källunge Church, to which it was sold in 1684.[45] At that time it was replaced by a sandstone altarpiece made in Burgsvik on Gotland, today preserved in the cathedral in one of the aisles. It contains the monograms of King Charles XI of Sweden and Queen Ulrika Eleonora.[46]

A rood cross from the 15th century from the cathedral is today preserved in Gotland Museum. It is inspired by the so-called Holy Face of Lucca.[47] The cathedral is still in possession of a 13th-century wooden sculpture of the resurrected Christ, placed in the rood.[48] A church tabernacle made of oak and dating from the middle of the 13th century is also still in the cathedral.[49] The decorated wooden pulpit dates from 1684. It was a gift by a trader and later mayor of Visby, Johan Wolters, who had moved to Visby from Germany in 1684.[50] Of more recent date is a nativity scene, displayed at Christmas annually, made in 1981 by Margaretha Ingelse.[51]

All the windows of the cathedral probably contained medieval stained glass once, but none have been preserved.[52] The three stained glass in the east wall of the chancel were installed in 1892 and were made by Karl de Bouché in Munich, inspired by the medieval stained glass in Bourges Cathedral.[53] The five windows in the great chapel are made by artist Per Andersson, installed between 1985 and 1990. Each window has a theme: "the guardian of truth", "the vine", "New Jerusalem", "the Apocalypse" and "the gardener".[54]

The cathedral has five church organs. The oldest is from 1599, and has been restored in modern times by Grönlunds Orgelbyggeri. It is located on the west gallery above the nave. The so-called large organ is from 1892 and located on a gallery above the north aisle. Two smaller, modern organs stand on the floor next to the pulpit and in the north aisle. The organ in the great chapel was originally built for Klinte Church and dates from 1870.[55] In addition, the church is also in possession of a harpsichord, placed in the chancel, which earlier belonged to harpsichordist Eva Nordenfelt.[55] There is also a carillon with 45 bells from 1960.[56]

Visby Cathedral also contains a large amount of tombstones and funerary memorials. The oldest dates from the 14th century, and the last was installed in the church during the 18th century.[57] Among these, there is the grave of Eric, son of Albert, the Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and at one time king of Sweden.[58] There is also a memorial in remembrance of the sinking of a Danish-Lübeck fleet outside Visby in 1566 and the German admiral and mayor of Lübeck Bartholomeus Tinnapfel. [57] More recent memorials are dedicated in remembrance of the sinking of the Swedish passenger ship SS Hansa in 1944 by a Soviet submarine, refugees from the Baltic states, the sinking of MS Estonia in 1994, and the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami.[58][59]

Use and heritage status

[edit]Visby Cathedral belongs to the Church of Sweden and is the seat of the Bishop of Visby.[60] It is an ecclesiastical monument, listed in the buildings database of the Swedish National Heritage Board.[61] The cathedral is one of the major tourist sites on Gotland. In 2008, it was visited by over 205,000 people.[62]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Svahnström 1978, p. 42.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Svahnström 1978, p. 9.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Andrén 2017, p. 106.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Svahnström 1978, p. 10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Lagerlöf & Svahnström 1991, p. 46.

- ^ Andrén 2017, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Lagerlöf & Svahnström 1991, p. 48.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ullén 1996, p. 74.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Historik" [History]. Diocese of Visby (in Swedish). Church of Sweden. 18 April 2016. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 173.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 190.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 193.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 194.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Lagerlöf & Svahnström 1991, pp. 48–50.

- ^ "Renovering av Sankta Maria" [Renovation of Sankta Maria]. Diocese of Visby (in Swedish). Church of Sweden. 18 January 2017. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 25.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 28.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ullén 1996, p. 73.

- ^ Ullén 1996, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 47.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 77.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 49.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 156.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 52.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 55–56.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 56.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, pp. 56–59.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, pp. 150–152.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 155.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Svahnström 1978, p. 80.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 84.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, pp. 84–95.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 96.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 99.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, pp. 99–106.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 106.

- ^ Svahnström & Svahnström 1986, p. 12.

- ^ Andrén 2017, p. 108.

- ^ Svahnström & Svahnström 1986, p. 14.

- ^ Svahnström & Svahnström 1986, p. 21.

- ^ Svahnström & Svahnström 1986, p. 23.

- ^ Svahnström & Svahnström 1986, p. 31.

- ^ Svahnström & Svahnström 1986, p. 35.

- ^ "Julkrubban" [The nativity scene]. Diocese of Visby (in Swedish). Church of Sweden. 19 December 2017. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, p. 72.

- ^ Svahnström 1978, pp. 72–73.

- ^ "Fönster" [Windows]. Diocese of Visby (in Swedish). Church of Sweden. 18 April 2016. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Instrument" [Musical instruments]. Diocese of Visby (in Swedish). Church of Sweden. 15 August 2020. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ "Svenske konsertklokkespill" (in Danish). Nordisk selskap for campanologi og klokkespil. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Svahnström & Svahnström 1986, p. 84.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lagerlöf & Svahnström 1991, p. 50.

- ^ Neuman, Jonas (26 December 2005). "Biskopen talade vid minnesstunden" [The bishop spoke at the memorial event]. Sveriges Radio (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 22 July 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "Visby S:ta Maria domkyrka" [Visby Saint Mary's Cathedral]. Diocese of Visby (in Swedish). Church of Sweden. 5 June 2018. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "GOTLAND VISBY S:TA MARIA 23 - husnr 1, VISBY DOMKYRKA (SANKTA MARIA KYRKA)" (in Swedish). Riksantikvarieämbetet (Swedish National Heritage Board). Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Visby domkyrka fick flest besök" [Visby Cathedral got most visitors]. gotland.net. Gotlands Media AB. 3 November 2008. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

Works cited

[edit]- Andrén, Anders (2017). Det Medeltida Gotland. En arkeologisk guidebok [Medieval Gotland. An archaeological guidebook] (in Swedish) (2 ed.). Lund: Historiska Media. ISBN 978-91-7545-476-4.

- Lagerlöf, Erland; Svahnström, Gunnar (1991). Gotlands kyrkor [Churches of Gotland] (in Swedish) (4th ed.). Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. ISBN 91-29-61598-4.

- Svahnström, Gunnar (1978). Visby domkyrka. Kyrkobyggnaden [Visby Cathedral. The building.] (PDF). Sveriges kyrkor, konsthistoriskt inventarium (in Swedish). Stockholm: Almqvist & WIksell. ISSN 0284-1894.

- Svahnström, Gunnar; Svahnström, Karin (1986). Visby domkyrka. Inredning [Visby Cathedral. Furnishings.] (PDF). Sveriges kyrkor, konsthistoriskt inventarium (in Swedish). Stockholm: Almqvist & WIksell. ISSN 0284-1894.

- Ullén, Marian (1996). "Gotikens kyrkobyggande" [Church building during the Gothic era]. In Augustsson, Jan-Erik (ed.). Signums svenska konsthistoria. Den gotiska konsten [Signum's history of Swedish art. Gothic art] (in Swedish). Lund: Signum. pp. 37–134. ISBN 91-87896-23-0.

External links

[edit] Media related to Visby Cathedral at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Visby Cathedral at Wikimedia Commons