Withrow, Minnesota

Withrow, Minnesota | |

|---|---|

Aerial photo of Withrow in 1964 | |

| Coordinates: 45°07′27″N 92°53′51″W / 45.12417°N 92.89750°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Minnesota |

| County | Washington County |

| Elevation | 981 ft (299 m) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 55038 and 55082 |

| Area code | 651 |

| GNIS feature ID | 654293[1] |

Withrow is an unincorporated community located in the city of Grant, Washington County, Minnesota, United States.[2][1] Formerly an unincorporated village on the edge of the Minneapolis–St. Paul metropolitan area, Withrow was located in three different local government jurisdictions: May Township, Grant Township, and Oneka Township.[3] The village had a post office and general store in May Township and a railroad station in Oneka.[4] Withrow is located 6 miles (9.7 km) northeast of White Bear Lake and 6.4 miles (10.3 km) northwest of Stillwater.[5]

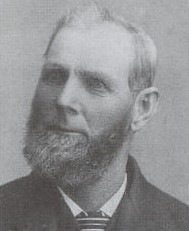

Withrow was established when the Minneapolis and St. Croix Railroad, which later merged with the Soo Line Railroad, was extended through Washington County in 1883.[6][7][8] The village was named after Thomas Joshua Withrow, a farmer from Nova Scotia who had settled in the area in 1874.[6] The well-drained, sandy soils around Withrow made it ideal for growing potatoes.[6][9][10] Withrow was formally platted in 1914, but it was never incorporated; a petition to incorporate was denied in 1947, since Withrow did not meet the population requirement of fifty inhabitants.[6][11][12] Immigrants to the area were primarily French-Canadian, Irish, and German.[7][13]

The center of Withrow today is generally considered to be the intersection of Keystone Avenue North and 119th Street North. The portion of the community that was located in Section 36 of Oneka Township was absorbed by Hugo in January 1972;[14][15] the portion that was located in Section 2 of Grant Township was absorbed into Grant when it was incorporated as a city in November 1996.[16][17] A small portion of Withrow existed in Section 31 of May Township; that section contains the Keystone Weddings and Events Center (formerly the Withrow Ballroom) and the cemetery.[6][16]

The Stillwater Area School District, ISD #834, maintained an elementary school at Withrow until 2017.[18] Withrow is currently considered to be a distinct residential and business district instead of an official village. Today, the district contains a few small businesses, a private school, and a handful of residential homes.[6]

History

[edit]The three townships that now contain parts of Withrow were surveyed in 1847 and 1848.[19][20]

The Withrow family and notable Withrow residents

[edit]

The settlement was named for Thomas Joshua Withrow.[4][11]

Establishment and community

[edit]The Minneapolis & St. Croix Railroad was extended through Washington County in 1883, giving rise to the village of Withrow.[8][21] A cooperative creamery was built south of the tracks in 1896, bringing farmers into the area on a daily basis.[6][22] An ice house was located behind the creamery, containing ice blocks harvested from School Section Lake, about 1 mile (1.6 km) north of Withrow; the ice kept the butter cool during warm weather.[23] A separate creamery building housed the butter maker.[24] The Withrow Creamery gained much prestige and a larger market after winning second prize for best creamery butter at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904.[6] Butter was originally sold in bulk form only; later, it was cut in 1-pound (0.45 kg) blocks and wrapped.[22] The creamery closed in 1930[6] and later became a feed mill, a restaurant, the Onekan store, and then a bar with risqué entertainment, Stan's Withrow Junction, before burning in a fire reported by the Soo Line depot agent in the early morning hours on November 22, 1979.[11][23][25]

South of the creamery, the Interstate Lumber Company maintained a machine shop which sold Minnesota Machinery farm equipment made by inmates at the state prison, as well as repair parts and hardware.[6][26] After the lumberyard burned down in 1944,[27] Interstate Lumber made a large addition to this building to accommodate their lumber sales, but sold the building due to dwindling sales. The former machine shop was later used as a manufacturing facility for fiberglass toboggans, a cabinet shop and construction business, a residence, a beauty shop, a convenience store, and two taverns, and became the east side of Sal's Angus Grill in 2003.[28][29] Interstate Lumber Company also owned a coal shed near the depot. Coal from rail cars would be unloaded in the building, and wagons would be backed up behind the building to pick up an order of coal.[30] Lumber was unloaded at the depot and reloaded on to horse-drawn wagons for transport to the lumber yard.[27]

By the early 1900s the village had acquired several general stores selling a variety of items including general merchandise, produce, grain, flour, hay rakes, and fresh butchered meats.[6][31] A blacksmith provided horseshoeing, wagon repair, and other metal fabrication.[6][32] Potato warehouses stored 150-pound (68 kg) bags of potatoes until they could be shipped by rail to market.[6][9] A combination barbershop and pool hall was the only place in town where one could get a hair cut, shoot pool, have a sandwich, and purchase an ice cream cone; dry cleaning could also be dropped off there for pickup by a company in Stillwater.[11][33] Adjacent to the barbershop and pool hall was a well-fortified building, constructed in 1913, which housed the Withrow State Bank.[6][34] The bank was robbed only once, around 1920, and was permanently closed in 1923. The building was leased afterwards as living quarters, then housed the post office in the mid- to late 1940s.[24] By 1910 there was also a Chevrolet dealership and garage, which generated power using gasoline engines to run the lights in the dance hall above the Kinyon Store.[6][33] The land south of the railroad tracks was surveyed and platted into lots; the map was filed at the Washington County Courthouse on December 13, 1914.[6][35] In 1947 the community voted to incorporate as a village, but the petition was denied because Withrow did not meet the population requirement of fifty inhabitants.[6][11][32]

Withrow was a viable community while the railroad dominated shipping. However, in the 1920s, roads were being improved, and farmers started hauling their own potatoes and cattle to market, and milk producers from Minneapolis–St. Paul began picking up milk directly from the farms.[6] Less grain such as wheat, oats, and barley were being grown, and the grain elevator ceased operation in the mid-1920s.[6][36] A special train carrying cattle would come through Withrow every Wednesday at 8:00 pm. Farmers would bring their cattle to the stockyard, weigh them on a nearby scale, and load them into a stock car bound for the stockyards in South St. Paul. This practice also ended in the mid-1920s, and the stockyard was dismantled.[6] A feed mill was located on the north side of the tracks, next to the Lambert General Store, which sold mainly groceries, candy and ice cream; a pool table and barbershop were located in the basement.[34][6] The grinder of the feed mill was run by a 20-horsepower gasoline engine with a 10-foot-high (3.0 m) flywheel which was located in the basement of the building. It made a distinctive noise which could be heard from some distance away. The store's proximity to the depot made it a favorite for passengers waiting for a train and railroad workers alike. Fire destroyed the store in the early 1920s.[37] The Germans constructed the only church in the area, St. Matthew's Lutheran church, 1.5 miles (2.4 km) southeast of Withrow. A wooden church was built in 1874 and replaced with a brick structure in 1899. In 1904 it burned down after a lightning strike and was rebuilt except for the steeple.[38] The church is now home to the St. Croix Ballet.[39]

At the height of its population from 1900 to 1950, Withrow had a baseball team, the Gophers,[40][41][42] a Woodmen of the World Camp,[43] a Mothers club,[44][45][46] a 4-H club,[47] and a Community Club.[48][49][50][51] The Community Club was the focal point of social activity in Withrow. It was founded in the early 1920s and held monthly meetings. The membership fee included free admission to club-sponsored dances at Zahler's Withrow Ballroom. It disbanded in 1949 as residents lost interest.[52] As late as 1978, Withrow also had a Girl Scout troop, #1292,[53] and as late as 2012, a Boy Scout troop, #169.[54]

Withrow is a popular destination for bicyclists and motorcyclists. The March of Dimes utilized the old Chevrolet garage at the intersection of Keystone Avenue (formerly Washington County Road 68, formerly Washington County Road 8) and Washington County Road 9 as a checkpoint for their Bike-A-Thon fundraisers in the 1970s,[55] and many Twin Cities bicycle clubs conduct time trials on a 13-mile (21 km) circuitous route that begins and ends at the former Withrow Elementary School.[56] The Warlords motorcycle club was founded in Withrow in 1972.[57]

Post office

[edit]

Withrow had an official U.S. post office from 1890 to 1963,[4][58] and a rural branch office from 1963 to 1966.[6] The post office opened on June 11, 1890,[6] in the rear of the B. W. Ellis general store; Ellis was the postmaster. In 1909 fire destroyed the store, and stamps and documents pertaining to the U.S. postal service were lost.[59] After the fire, Clarence LeRoy Kinyon, who had been the mail carrier, reopened the store and post office, selling hardware, groceries, fabric, and clothing.[6][60] The post office relocated to the former Withrow State Bank building in the mid- to late 1940s, and relocated again to the former Kinyon house, which had been purchased by William and Vivian Guse, in 1950; the post office was moved to the porch of the house, where residents could pick up mail from their P.O. boxes, buy stamps, and mail packages. Vivian Guse was the postmistress until 1966. The mail pouch was brought to the train depot daily and hung on the mail hook, where it was picked up by a passing train. In 1962 the Guses opened the Withrow Tavern and a small grocery store selling Gulf gasoline in the old creamery building, locating the post office there until mail delivery was taken over by rural route carrier.[6][26] The Kinyon general store building was destroyed by fire in 1981.[24]

Railroads

[edit]

The rise of the lumber industry quickly led to population booms in cities like Stillwater, and railroads hauled the lumber.[7][11] Communities sprang up around the railroads.[11] The Minneapolis & St. Croix Railroad was extended through Washington County in 1883;[21][61] in 1888, this railroad merged with three others to form the Soo Line Railroad.[6][7][8]

Two rail lines converged at Withrow, making it an important railway and telegraph station; in 1887, a depot was built that turned out to be far larger than the village ever needed.[3][23] At one point, the railroad maintained telegraph operators and depot agents 24 hours a day, with at least one permanently assigned depot agent.[62] It was a busy place, with nearly thirty freight trains and passenger trains coming through town daily, and a favorite rest stop for transients riding the rails.[34] The rail crossing at Withrow took a heavy toll of victims over the years.[63] After the creamery closed, the Soo Line bought the building which had housed the butter maker as a residence for the station agent.[24] The number of trains dropped to sixteen in the early 1960s; only four of those were passenger trains, and Withrow became a flag stop.[23] Like many towns dependent on the railroad, Withrow lost much of its industry with the passing of the railroad era.[14] The Soo Line discontinued passenger service to Withrow in 1963.[6][62]

In July 1990, a Soo Line crane and flatcar traveled to Withrow and demolished the Withrow depot.[6][64]

The Canadian National Railway's Dresser Subdivision at Withrow has been taken out of service.[65]

Schools

[edit]Before 1955, there were three schools located in the Withrow area. Each school was known by a number. School #10, a one-room schoolhouse, was on 100th Street and Lansing Avenue North.[37] School #40, another one-room schoolhouse, was located on Lynch Road.[6][37] On the west side of the intersection of Washington County Road 7 and County Road 8A in Oneka Township was a third one-room school, #51, built in 1871.[18] The first teacher at this school was Mary Withrow, with an enrollment of 32 students. Clarence LeRoy Kinyon owned 100 acres (40 ha) straddling County Road 7 at this location,[66] and this school came to be known as the Kinyon School.[18] In 1877 a new school district was organized, and this school was renumbered #63.[6][37] Thomas Withrow became a member of the new school board, and enrollment increased to 56 students, with Lizzie Withrow appointed as the teacher.[18]

In March 1952 the Board of Education for the Stillwater area made the recommendation to replace the inadequate school buildings with a new school with more classrooms to provide for increased enrollment. The specific recommendation was to purchase a site of at least 5 acres (2.0 ha) in or near Withrow as the site of a new elementary school. The school was to have three classrooms, a kindergarten, a multi-purpose room, and office and storage space. The estimated cost of construction was $165,000. The school was built in 1955 in the southeast corner of what was then Oneka Township, north of County Road 7, about 1 mile (1.6 km) west of the intersection with County Road 15, on 9 acres (3.6 ha) of land originally owned by Thomas Withrow.[6][37][67] Many additions were made over time, with the last addition to the building made in 1997.[18] In 2008 Withrow Elementary was used as a location for the film Killer Movie.[68]

Withrow Elementary was in the Stillwater Area School District, ISD #834, and served 219 students from kindergarten through sixth grade. A STEM school, it was ranked fourteenth among 842 elementary schools in Minnesota, with specialists in music, physical education, media, and art. In 2012 it was rated a National Blue Ribbon School by the U.S. Department of Education.[18]

In December 2015 the Stillwater Area School District, as a part of its Building Opportunities to Learn and Discover (BOLD) program,[69][70] proposed the closure of Withrow Elementary along with two other elementary schools in the northern part of the school district due to low enrollment, despite the passage of a $97.5 million bond earlier that year that would have funded improvements to Withrow Elementary.[71] Parents protested, fearing that placement of students into larger schools and classrooms would result in lower standardized test scores and academic performance, and higher dropout rates, school violence, and bullying.[72][73][74] The school district argued that the closures and reallocation of funds were necessary due to population growth in the southern half of the school district.[75] Several legal challenges were filed against the school district, individual school board members, and school district administrators, citing significant conflicts of interest and open-meeting violations. Despite these protests and legal challenges, Withrow Elementary was closed on May 31, 2017.[69]

On November 4, 2021, the Stillwater Area School District accepted an offer of $1.4 million for the vacant Withrow Elementary School from an anonymous donor on behalf of a private school, Liberty Classical Academy.[76][77][78]

Withrow Ballroom

[edit]

The Kinyon general store had a dance hall on the second floor and held dances on Saturday nights.[11] Dances were well attended, and the hitching rail to the south of the building was often full of horses.[27] There was no indoor plumbing at the time, so the dance hall's lavatory, attached to the back of the building, was a two-story outhouse. The dance hall was condemned by the state as a fire hazard having only one exit in the late 1920s.[24] Bernard and Anna Zahler, who lived on the old Withrow farm, offered to build a new ballroom. They bought the empty grain elevator, had it dismantled, and used the lumber to build a new ballroom. Zahler's Withrow Ballroom was built on the 12-acre (4.9 ha) site of the old blacksmith shop in 1928,[11] and is the oldest ballroom in the state of Minnesota.[6] The first dance was held on the Fourth of July. The band was a local group of musicians who were paid five dollars each. Admission was 25 cents, soft drinks were five cents, and near beer (a beverage that arose during Prohibition) was available to patrons.[79] Identified as an historic landmark in May Township, the 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) ballroom and 3,000-square-foot (280 m2) hardwood dance floor are widely regarded as one of the best rooms for live music in the Twin Cities.[80][81] The couple sold the ballroom to their son, Ed Zahler Sr., in 1946, after managing the place for nearly twenty years. Ed Zahler Sr. received a liquor license for the Withrow Ballroom in 1950.[6] It was basically a BYOB license, so customers would bring their own bottles, but the bar would sell the mixers. Ed and Gertrude Zahler continued the tradition of polka dances, but during the late 1950s, musical tastes started to change. Rock and roll became more popular than the traditional polka music of the area's German immigrant farmers, and Ed began to introduce rock and roll music, playing rock records during intermissions. Ed Zahler Jr. purchased the ballroom from his father in 1974, adding large picture windows,[79] food, and a kitchen, and made the venue available for weddings and catered events.[82]

After ownership by three generations of Zahlers, Marvin and Mary Jane Babcock purchased the ballroom from Ed Zahler Jr. in 1983, renaming it the "Withrow Ballroom", and turning it over to their son Mark and his future wife Lori in 1985.[82] When Mark Babcock purchased the facility, the Withrow Ballroom was a white rectangular box in the middle of a corn field. At that time Washington County had more horses per capita than anywhere else in the country,[83][84] so Babcock added a gazebo to the property and had the place remodeled to look like a Kentucky horse farm, complete with cupolas on the roof, an arched entrance, and 3,000 feet (910 m) of white fencing.[82][85] The ballroom was sold to Keith and Kim Warner in 1997,[86][87] then to Scott and Kimberly Aamodt in 2001.[79][88] The Aamodts added dance lessons with the concept of expanding the Withrow Ballroom to include a future conference center, motel, bar, and restaurant.[89] The ballroom closed on November 1, 2008, a consequence of the great recession, and the building went into foreclosure. A pending sale of the Withrow Ballroom fell through in February 2009, when prospective owner Molly Behmyer withdrew her application to May township for a conditional use permit, which would have allowed the ballroom to remain open seven days a week.[90][91] John Rawson of Hugo subsequently formed the non-profit Withrow Historical Society in the hope of acquiring and preserving the Withrow Ballroom.[92][93][94] In November 2009 Paul Bergmann bought the ballroom and expanded the facility's events to include a dinner theater and classic car and tractor shows,[95][96][97] selling the Ballroom at auction in 2017 to Laura Miron Mendele.[98][99][100] Lawrence Xiong purchased the facility from Mendele in December 2019, who rebranded the ballroom as the Keystone Wedding and Events Center.[101][102][103][104]

Many popular musicians have played at the Withrow Ballroom, including the Six Fat Dutchmen, the Lamont Cranston Band, Bobby Z., and Grammy-award winning musicians Yanni and Jonny Lang,[105] in addition to many local bands and comedians, including Kevin Farley.[106][107][108] The Withrow Ballroom has hosted the Minnesota Bluegrass and Old Time Music Festival and the Minnesota State Polka Festival.[79] It has been the setting for hundreds of fundraisers (including a fundraiser for Zach Sobiech),[109][110][111] and a venue for conferences, class reunions, wedding receptions, ceremonies and anniversaries.[105][112][113][114]

Geography

[edit]Withrow is located in the Eastern Broadleaf Forest Province in the ecological subsection of the St. Paul–Baldwin Plains, which consists of oak woodland, oak savanna, and prairie.[19][115] Oak woodland and brushland was a common ecotonal type between tallgrass prairie and the Eastern deciduous forest. When the area was originally settled, vegetation consisted of oak openings and barrens: scattered areas and groves of oaks (mostly bur oak and pin oak) of scrubby form, with some brush and occasional pines, maples, and basswoods.[116][117] Land cover today mostly consists of cultivated crops, pasture, and hay, along with scattered deciduous forests of oak and aspen, hazelnut thickets, and prairie openings.[118] A grove of black walnut trees lines the east side of Keystone Avenue at its intersection with County Road 9.[119]

Brown's Creek has its source near Withrow.[120]

The bedrock formations of Washington County at Withrow are part of regionally extensive, gently sloping layers of sandstone, shale, and carbonate rock.[121]

Climate

[edit]Withrow is in the northern continental United States and is characterized by a cool, subhumid climate with a large temperature difference between the summer and winter seasons. Winters are very cold, and summers are fairly short and warm. Snow covers the ground much of the time from late fall through early spring. Average summer temperatures are approximately 70 °F (21 °C) June through August, and winter temperatures are approximately 18 °F (−8 °C) December through February.[122][123] July is the warmest month, when the average high temperature is 80 °F (27 °C) and the average low is 63 °F (17 °C). January is the coldest, with an average high temperature of 21 °F (−6 °C) and average low of 3 °F (−16 °C). Its Köppen climate classification is Dfa. Annual normal precipitation ranges from 28 inches (71 cm) in the north to 31 inches (79 cm) in the south, and the growing season precipitation averages 12.5–13 inches (32–33 cm). The average growing season length ranges from 146 to 156 days.[116] Normal annual snowfall totals about 50 inches (130 cm).[124] It was a newsworthy event whenever the snowplow came through Withrow.[48][125][126]

Withrow lies at an elevation of 981 feet (299 m) in Washington County, Minnesota, 15 miles (24 km) northeast of St. Paul.[1] Withrow is located 6 miles (9.7 km) northeast of White Bear Lake and 6.4 miles (10.3 km) northwest of Stillwater, 2.9 miles (4.7 km) north of Minnesota State Highway 96 and 5.2 miles (8.4 km) east of U.S. Highway 61.[5] The last year Withrow appeared on the Official Minnesota State Highway Map was 2012.[127]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() Media related to Withrow, Minnesota at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Withrow, Minnesota at Wikimedia Commons

- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Withrow

- ^ "City of Grant - Road plan". www.co.washington.mn.us. November 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Schmitt, Wilma J (August 15, 1993). "Withrow in the Twenties". Country Messenger (MN). p. 15.

- ^ a b c Upham 2001, p. 620.

- ^ a b Minnesota Official Highway Map (Metropolitan Minneapolis and St. Paul) (Map). [1:155,963]. Minnesota Department of Transportation. 2009–2010. Archived from the original on October 14, 2022. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag "Ghost Towns of Washington County: Withrow Once a Prosperous Settlement". Historical Whisperings. 39 (2). Washington County Historical Society: 9. July 2013.

- ^ a b c d Scobie 1983, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Leighton 1998, p. 34.

- ^ a b Scobie 1983, pp. 6, 14.

- ^ "Withrow Farmer Raises 'Paul Bunyan' Spuds". Stillwater Post-Messenger (MN). October 10, 1946. p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Powell, Joy (May 24, 1983). "Withrow Story Told". Stillwater Gazette (MN). p. 3.

- ^ Scobie 1983, pp. 2, 5.

- ^ Washington County Historical Society 1977, pp. 12, 176, 193.

- ^ a b Washington County Historical Society 1977, p. 224.

- ^ Peterson, Brent (January 7, 2019). "Hugo's History". Forest Lake Times. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ a b The Farmer, A Journal of Agriculture 1912, p. 3.

- ^ "Grant History". City of Grant, Minnesota. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "About Withrow Elementary". Stillwater Area Public Schools. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ a b "Washington County, Minnesota". Living Places. Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ Washington County Historical Society 1977, p. 186.

- ^ a b "Grant". Washington County Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Scobie 1983, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Scobie 1983, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e Scobie 1983, p. 8.

- ^ Gillstrom, John (November 23, 1979). "Financially-Troubled Bar Destroyed by Fire". Stillwater Gazette (MN). Vol. 95, no. 231. p. 1.

- ^ a b Scobie 1983, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Scobie 1983, p. 7.

- ^ Scobie 1983, pp. 11, Addendum.

- ^ "Withrow Ballroom". Country Messenger (MN). August 18, 1993. p. 15.

- ^ Scobie 1983, p. 14.

- ^ Scobie 1983, p. 6.

- ^ a b Scobie 1983, p. 5.

- ^ a b Scobie 1983, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Scobie 1983, p. Addendum.

- ^ Scobie 1983, p. 2.

- ^ Scobie 1983, pp. 3, 13.

- ^ a b c d e Scobie 1983, p. 15.

- ^ Scobie 1983, p. 16.

- ^ "St. Croix Ballet". Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "The County: Withrow". Stillwater Weekly Gazette (MN). May 14, 1902. p. 6.

- ^ "The County: Withrow". Stillwater Weekly Gazette (MN). May 21, 1902. p. 5.

- ^ "The County: Withrow". Stillwater Weekly Gazette (MN). June 18, 1902. p. 8.

- ^ "Social Event At Withrow: The Opening of the Woodmen's New and Commodious Hall". Stillwater Gazette (MN). November 4, 1903. p. 1.

- ^ "Washington County". Stillwater Post-Messenger (MN). May 1, 1929. p. 8.

- ^ "Washington County". Stillwater Post-Messenger (MN). February 6, 1929. p. 7.

- ^ "Washington County". Stillwater Post-Messenger (MN). April 10, 1929. p. 7.

- ^ "Washington County". Stillwater Post-Messenger (MN). April 24, 1929. p. 8.

- ^ a b "Washington County". Stillwater Post-Messenger (MN). March 20, 1929. p. 7.

- ^ "Washington County". Stillwater Post-Messenger (MN). April 17, 1929. p. 7.

- ^ "Washington County". Stillwater Post-Messenger (MN). May 8, 1929. p. 7.

- ^ "Washington County". Stillwater Post-Messenger (MN). May 15, 1929. p. 6.

- ^ Scobie 1983, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Valentine, Dotty (April 11, 1978). "Withrow Girl Scouts Begin Tour of Washington D.C.". Stillwater Evening Gazette (MN).

- ^ Barnes, Deb (April 28, 2012). "Troop 169 Serves Up Breakfast at Sal's". The Citizen (MN). Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "March of Dimes to Sponsor Rides". Minneapolis Tribune (MN). August 7, 1972. p. 6A.

- ^ "Withrow Time Trials". Now Bikes. Archived from the original on September 7, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "History". Warlords Motorcycle Club Minnesota. Archived from the original on November 1, 2022. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ Washington County Historical Society 1977, p. 298.

- ^ "Fire at Withrow". Stillwater Post-Messenger (MN). February 6, 1909. p. 4.

- ^ Scobie 1983, pp. 2, Addendum.

- ^ "Brown's Creek State Trail Public Open House Historic and Cultural Resources" (PDF). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 12, 2022. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Scobie 1983, p. 13.

- ^ "Pioneer Settlers Killed by Train at Withrow". Stillwater Daily Gazette. October 11, 1921. p. 1.

- ^ Dethmers, Tom. "End of the Withrow Depot". Railroad Picture Archives. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ "Seventh Subdivision of the Central Division (Weyerhauser Line)". Mileposts Along the Soo Line. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ The Farmer, A Journal of Agriculture 1912, p. 9.

- ^ The Farmer, A Journal of Agriculture 1912, p. 7.

- ^ "Killer Movie (2008) – Filming and Production". IMDb. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Bryant, Shannon (May 25, 2017). "Community Gathers to Say Goodbye to Withrow Elementary". The Grant Reporter. Retrieved September 12, 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Stillwater School Board May Vote to Close 3 Elementary Schools". CBS Minnesota. March 3, 2016. CBS. WCCO 4. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ John Lauritsen (January 28, 2016). "Parents Demand Stillwater Schools Stay Open". CBS Minnesota. CBS. WCCO 4. Archived from the original on September 12, 2022. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ John Lauritsen (January 5, 2016). "Parents Rally Against Stillwater School Closings". CBS Minnesota. CBS. WCCO 4. Archived from the original on September 12, 2022. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ Neutkens, Debra (January 7, 2016). "Parents Rally to Fight Possible School Closing". The Citizen. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ Magan, Christopher (January 3, 2016). "Stillwater Elementary School Parents Protest Planned Closings". St. Paul Pioneer Press (MN). Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ "Community Meeting To Be Held To Address Potential Stillwater School Closings". CBS Minnesota. January 7, 2016. CBS. WCCO 4. Archived from the original on September 12, 2022. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ DeBow, Matt (November 12, 2021). "School Board OKs Withrow Sale". Stillwater Gazette (MN). Archived from the original on December 4, 2021. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ Devine, Mary (November 8, 2021). "Stillwater Board Agrees to Sell Withrow Elementary to White Bear Lake Private School". St. Paul Pioneer Press (MN). Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ Granholm, Shannon (June 29, 2022). "Private School Breathes New Life into Withrow Elementary Building". White Bear Press (MN). Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Dubbe, Jackie (January 3, 2008). "Let the Good Times Roll". St. Croix Valley Press (MN). pp. 3–5. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Janisch, Kris (December 10, 2007). "Having a Ball for 80 Years: Withrow Ballroom Gearing Up for Eight Decades of Operation". Stillwater Gazette (MN). pp. 1–2.

- ^ Divine, Mary (July 31, 2008). "Withrow Ballroom May Take Final Bow". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c Ostrom, Lee (April 13, 1992). "Babcocks Make Memories: Withrow Ballroom is Where 'Wonderful Things Happen'". The Courier News (MN). pp. 1, 14.

- ^ Collins, Bob (October 27, 2017). "The Music Stops at the Withrow Ballroom". Minnesota Public Radio. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ Bussjaeger, Jackie (March 2, 2020). "A Matter of Horse: Washington County's Love for All Things Equine". The Lowdown. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ Allen, Emily (February 16, 2018). "In Ownership Change, Hugo's Withrow Ballroom Finds New Life". Minneapolis Star Tribune (MN). Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Rettke, Naomi (February 8, 2001). "Turning it All Around: After Years of Building Her Skills and Reputation, Chef Kim Warner Has Taken on a New Project at the Withrow Ballroom". St. Croix Valley Press (MN). p. 8.

- ^ Davis-Johnson, Carroll (July 30, 1997). "A Fresh Look for the Withrow Ballroom". Country Messenger (MN). p. 8.

- ^ "Aamodts Buy Withrow Ballroom". Stillwater Gazette (MN). February 12, 2002. p. 2.

- ^ Blomberg, Kelly (October 4, 2006). "May Considers Withrow Expansion: Withrow Ballroom May Add Motel". Country Messenger (MN). p. 2.

- ^ Blomberg, Alana (November 12, 2008). "Withrow Ballroom Uses Back on Table". The Lowdown (MN). Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Miron, Michelle (February 5, 2009). "No Deal Yet for Purchase of Old Withrow Ballroom". St. Croix Valley Press (MN).

- ^ Divine, Mary (June 12, 2009). "Man Wants Bank to Donate Ballroom". St. Paul Pioneer Press (MN). p. 2B.

- ^ Neutkens, Debra (June 25, 2009). "Nonprofit Ready to Rescue Withrow Ballroom". St. Croix Valley Press (MN). p. 24.

- ^ Neutkens, Debra (November 5, 2009). "Withrow Reopens its Historic Doors". The Lowdown (MN). Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Barnes, Deb (January 27, 2011). "Withrow Ballroom to Host Dinner Theater". The Lowdown (MN). Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Barnes, Deb (May 17, 2012). "Who Dunnit at Withrow? Hint: It Wasn't the Caterer". St. Croix Valley Press (MN). p. 20.

- ^ Weaver, Kyle (November 11, 2009). "Ballroom Poised to Open This Month". Country Messenger (MN). p. 9.

- ^ Heidi Wigdahl (October 26, 2017). "Historic Withrow Ballroom to Close". Minnesota's Own KARE 11. NBC. KARE 11. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "The Historic Withrow Ballroom & Event Center Absolute Auction". Hines Auction Service. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Lebens, Alicia (January 15, 2018). "Withrow Ballroom Finds New Owner, Will Continue as Event Center". Stillwater Gazette (MN). Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ Lebens, Alicia (January 19, 2018). "New Owner Keeps Withrow Ballroom Open". Stillwater Gazette (MN). pp. A1, A8.

- ^ "Withrow Ballroom Celebrates Grand Re-opening". Country Messenger (MN). May 9, 2018. p. 1.

- ^ Devine, Mary (January 15, 2018). "She's in a Long-Ago Photo, a Tot in a Dress at the Withrow Ballroom. Now She Owns It". St. Paul Pioneer Press (MN). Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ "Withrow Ballroom has New Owner". Minnesota Ballroom Operator's Association. January 24, 2018. Archived from the original on September 28, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Lebens, Alicia (October 27, 2017). "Withrow Ballrooms Last Dance?". Stillwater Gazette (MN). pp. A1, A13. Archived from the original on December 6, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ "Kevin Farley at the Withrow Ballroom Presented by Scott Hansen's Comedy Gallery". Brown Paper Tickets. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "Withrow Ballroom Will Remain Event Center". Country Messenger (MN). January 21, 2018. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ "New Owner Plans to Keep Withrow Ballroom Hopping". White Bear Press (MN) (Press release). January 17, 2018. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Peterson, Brent (April 3, 2012). "More-Tishans to Play the Withrow Ballroom April 14". Oakdale Patch. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Cropp, Avery (December 26, 2012). "Sobiech Cancer Research Fundraiser a Success". Stillwater Gazette (MN). Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Kink, Julie (August 23, 2013). "Dance Hall Days: Withrow Ballroom Celebrates 85 Years of Fun and Matchmaking". The Lowdown (MN). pp. 1, 10. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Devine, Mary (October 27, 2017). "Last Dance for the Withrow Ballroom? Site's Being Sold". St. Paul Pioneer Press (MN). Archived from the original on November 4, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Divine, Mary (October 27, 2017). "Last Dance for what is Thought to be Oldest Ballroom in Minnesota". St. Paul Pioneer Press (MN). Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Kleinhuizen, Monique (November 2018). "Find the Perfect Wedding Venue in the St. Croix Valley". St. Croix Valley Magazine. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Lessard-Sams Outdoor Heritage Council (February 23, 2009). Forest Protection, Enhancement and Restoration in Minnesota (PDF) (Report). St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Legislative Coordinating Commission. pp. 1, 31. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 12, 2022. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "St. Paul-Baldwin Plains and Moraines Subsection". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ Wendt, Keith M.; Coffin, Barbara A. (1988). Natural Vegetation of Minnesota At the Time of the Public Land Survey 1847-1907 (PDF) (Report). St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. pp. 2, 3, 5, 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ "Land Cover in Minnesota at a 1 Kilometer Resolution". Retrieved September 12, 2022.[dead link]

- ^ Glavan, Gregory S.; Frank, Deborah A. (Spring 1984). The Isolation of a Phytotoxin: Juglone (Report). University of Minnesota College of Biological Sciences: Department of Plant Biology. p. 4.

- ^ "Browns Creek". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ "Paleozoic Geology". University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering. St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Geological Survey. Archived from the original on August 14, 2022. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ Berg, James A. (2019). Groundwater Atlas of Washington County, Minnesota County Atlas Series C-39, Part B (PDF) (Report). St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ^ United States, Department of Agriculture (1980). Soil Survey of Washington and Ramsey Counties, Minnesota (PDF) (Report). Washington: Government Printing Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ^ "Minnesota Annual Snow Normal". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on July 21, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ "Washington County". Stillwater Post-Messenger (MN). February 20, 1929. p. 7.

- ^ "Washington County". Stillwater Post-Messenger (MN). February 27, 1929. p. 7.

- ^ Official Minnesota State Highway Map (Metropolitan St. Paul Minneapolis) (Map). [1:155,963]. Minnesota Department of Transportation. 2011–2012.

Sources

[edit]- Blythe, Leslie H. (January 1994). National Park System Properties in the National Register of Historic Places (PDF). Washington: United States Department of the Interior. OCLC 41148845. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- Brandt, Marley (1992). The Outlaw Youngers, A Confederate Brotherhood. Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto and Plymouth, UK: Madison Books. ISBN 0-8191-8627-9. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- The Farmer, A Journal of Agriculture (1912). The Farmer's Atlas and Directory of Washington County Minnesota 1912. St. Paul, MN: Webb Publishing Company. OCLC 652998528. Archived from the original on September 7, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- Leighton, Hudson (1998). Gazetteer of Minnesota Railroad Towns, 1861–1997. Roseville, MN: Park Genealogical Books. ISBN 978-0-915709-61-8. Archived from the original on June 9, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- Sardeson, Frederick W. (1916). Geographic Atlas of the United States: Description of the Minneapolis and St. Paul District (PDF). Washington: United States Geological Survey. doi:10.3133/gf201. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- Scobie, Cathy (May 1983). Memories of Withrow. OCLC 824210495.

- Upham, Warren (2001). Minnesota Place Names: A Geographical Encyclopedia (Third ed.). St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-87351-396-8. Archived from the original on June 9, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- Washington County Historical Society (1977). Washington: A History of the Minnesota County. Stillwater, MN: Croixside Press. ASIN B000F3LWOU. OCLC 3913983.