Opisthiolepis

| Opisthiolepis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Foliage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Subfamily: | Grevilleoideae |

| Tribe: | Embothrieae |

| Subtribe: | Hakeinae |

| Genus: | Opisthiolepis L.S.Sm.[3][4] |

| Species: | O. heterophylla

|

| Binomial name | |

| Opisthiolepis heterophylla | |

Opisthiolepis is a monotypic (i.e. containing only one member) genus of trees in the macadamia family Proteaceae. The sole species is Opisthiolepis heterophylla, commonly known as blush silky oak, pink silky oak, brown silky oak or drunk rabbit. It was first described in 1952 and is endemic to a small part of northeastern Queensland, Australia.

Description

[edit]Opisthiolepis heterophylla is an evergreen tree growing up to 30 m (98 ft) tall with a trunk diameter of 75 cm (30 in).[2][5][6] The leaves are usually simple on mature trees and oblong to elliptic in shape. They measure up to 23 cm (9.1 in) long by 9 cm (3.5 in) wide and are carried on petioles (leaf stalks) up to 5 cm (2.0 in) long.[5][7] The leaves are glossy green above and silvery white or brown below.[5][7] Like many other species in the Protoeaceae family, the leaves vary in shape considerably and may also be compound with up to 18 leaflets.[5]

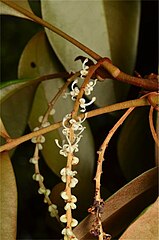

The inflorescence is a pendant spike produced in the leaf axils.[8] It measures up to 15 cm (5.9 in) and carries numerous small flowers in pairs.[5][7] The flowers are sessile (without a stalk) and glabrous (without hairs) and have 4 white or cream tepals up to 5 mm (0.20 in) long.[5][7][8]

The fruit is a green or brown woody follicle measuring about 12 by 3.5 cm (4.7 by 1.4 in) and containing several winged brown seeds.[7][8]

Taxonomy and naming

[edit]This species was first described by the Queensland botanist Lindsay Stuart Smith, based on a number of collections of material during the first half of the 20th century. Most collections were from the Atherton Tablelands with the exception of two – one from Mena Creek and another from the area that is now Kirrama National Park.[6]: 80

Smith published his paper, titled "Opisthiolepis, a new genus of Proteaceae from Queensland" in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland in 1952.[3][6]

The species is reported to share its evolutionary closest correlates with the genera Buckinghamia, Finschia, Grevillea and Hakea in the subtribe Hakeinae.[9][10][11] The genetics studies, still at an early stage,[when?] suggest Opisthiolepis may represent the continuing living lineage of the ancient branch off from near the base or from before the base of the entire present day subtribe Hakeinae.[9][11][12]

Etymology

[edit]The genus name Opisthiolepis is derived from the Ancient Greek words ὄπισθεν (ópisthe) meaning back or behind, and λεπίς (lepís) meaning scale or flake. It is a reference to the single nectar gland (scale) in the flower.[8] The species epithet heterophylla is also from Ancient Greek, and is a combination of héteros (héteros), different, and φύλλον (phúllon), leaf, which alludes to the different forms of the juvenile and mature leaves.[8]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]Opisthiolepis heterophylla is endemic to northeastern Queensland and is found in the area from near Cardwell north to about Mossman (including the Atherton Tablelands where it is common).[5][8] It grows in rainforest, on various soil types but grows best on those derived from basalt.[5][7] The altitudinal range is from near sea level to about 1,100 m (3,600 ft).[7][8]

Conservation

[edit]This species is listed by both the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the Queensland Department of Environment and Science as least concern.[1][2]

Cultivation

[edit]The blush silky oak grows quickly in cultivation, one specimen in John Wrigley's garden in Coffs Harbour reaching 6 m (20 ft) high and flowering in four years.[13]

Gallery

[edit]-

Underside of foliage

-

Green foliage

-

Inflorescence

-

Flowers

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Species profile—Opisthiolepis heterophylla". Queensland Department of Environment and Science. Queensland Government. 2022. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Forster, P., Ford, A., Griffith, S. & Benwell, A. (2020). "Opisthiolepis heterophylla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T118152028A122769076. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T118152028A122769076.en. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Opisthiolepis heterophylla". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI). Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research, Australian Government. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ a b "Opisthiolepis heterophylla L.S.Sm". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2023. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Foreman, D.B. (2022). "Opisthiolepis heterophylla". Flora of Australia. Australian Biological Resources Study, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water: Canberra. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Smith, Lindsay Stuart (1952). "Opisthiolepis, a new genus of Proteaceae from Queensland". The Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland. 62 (9): 79–81. doi:10.5962/p.351757. S2CID 257130577. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g F.A.Zich; B.P.M.Hyland; T.Whiffen; R.A.Kerrigan (2020). "Opisthiolepis heterophylla". Australian Tropical Rainforest Plants Edition 8 (RFK). Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research (CANBR), Australian Government. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cooper, Wendy; Cooper, William T. (June 2004). Fruits of the Australian Tropical Rainforest. Clifton Hill, Victoria, Australia: Nokomis Editions. p. 418. ISBN 9780958174213.

- ^ a b Weston, Peter H.; Barker, Nigel P. (2006). "A new suprageneric classification of the Proteaceae, with an annotated checklist of genera" (PDF). Telopea. 11 (3): 314–344. doi:10.7751/telopea20065733. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ Sauquet, Hervé; Weston, Peter H.; et al. (6 January 2009). "Contrasted patterns of hyperdiversification in Mediterranean hotspots". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (1): 221–225. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106..221S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805607106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2629191. PMID 19116275.

- ^ a b Mast, Austin R.; Milton, Ethan F.; et al. (1 March 2012). "Time-calibrated phylogeny of the woody Australian genus Hakea (Proteaceae) supports multiple origins of insect-pollination among bird-pollinated ancestors". American Journal of Botany. 99 (3): 472–487. doi:10.3732/ajb.1100420. PMID 22378833.

- ^ Duchene, David; Bromham, Lindell (13 March 2013). "Rates of molecular evolution and diversification in plants: chloroplast substitution rates correlate with species-richness in the Proteaceae". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 13 (1): 65. Bibcode:2013BMCEE..13...65D. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-65. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 3600047. PMID 23497266.

- ^ Wrigley, John; Fagg, Murray (1991). Banksias, Waratahs and Grevilleas. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. pp. 465–66. ISBN 0-207-17277-3.

External links

[edit] Data related to Opisthiolepis heterophylla at Wikispecies

Data related to Opisthiolepis heterophylla at Wikispecies Media related to Opisthiolepis heterophylla at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Opisthiolepis heterophylla at Wikimedia Commons- View a map of historical sightings of this species at the Australasian Virtual Herbarium

- View observations of this species on iNaturalist

- View images of this species on Flickriver