Paul Krassner

Paul Krassner | |

|---|---|

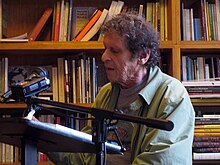

Krassner at City Lights Bookstore in 2009 | |

| Born | April 9, 1932 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | July 21, 2019 (aged 87) |

| Occupation(s) | Writer, satirist, activist, comedian |

| Spouse |

Jeanne Johnson

(m. 1963, divorced)Nancy Cain (m. 1987) |

| Children | 1 |

| Website | www |

Paul Krassner[1] (April 9, 1932 – July 21, 2019) was an American writer and satirist. He was the founder, editor, and a frequent contributor to the freethought magazine The Realist, first published in 1958. Krassner became a key figure in the counterculture of the 1960s as a member of Ken Kesey's Merry Pranksters and a founding member of the Yippies, a term he is credited with coining.[2][3][4]

Early life

[edit]Krassner was a child violin prodigy and performed at Carnegie Hall in 1939 at age six.[5][6] His parents practiced Judaism,[7][8] but Krassner chose to be firmly secular, considering religion "organized superstition".[9] He majored in journalism at Baruch College (then a branch of the City College of New York) and began performing as a comedian under the name Paul Maul. He recalled:

While in college, I started working for an anti-censorship paper, The Independent. After I left college I started working there full time. So, I never had a normal job where I had to be interviewed and wear a suit and tie. I became their managing editor and also did freelance stuff for Mad magazine. But Mad was aimed at a teenage audience, and there was no satirical magazine for adults. So it was a kind of organic evolution toward The Realist, which was essentially a combination of satire and alternative journalism.[10]

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, he was active in politically edged humor and satire. Krassner was a founder of the Youth International Party (Yippies) in 1967, even credited with coining the word "Yippie,"[2][3][4] and a member of Ken Kesey's Merry Pranksters, famous for prankster activism. He was a close protégé of the controversial comedian Lenny Bruce, and the editor of Bruce's autobiography, How to Talk Dirty and Influence People.[11] With the encouragement of Bruce, Krassner started to perform standup comedy in 1961 at the Village Gate in New York.[11]

In 1963, he created what Kurt Vonnegut described as

"a miracle of compressed intelligence nearly as admirable for potent simplicity, in my opinion, as Einstein's e=mc2." Vonnegut explained: "With the Vietnam War going on, and with its critics discounted and scorned by the government and the mass media, Krassner put on sale a red, white and blue poster that said FUCK COMMUNISM. At the beginning of the 1960s, FUCK was believed to be so full of bad magic as to be unprintable. ... By having FUCK and COMMUNISM fight it out in a single sentence, Krassner wasn't merely being funny as heck. He was demonstrating how preposterous it was for so many people to be responding to both words with such cockamamie Pavlovian fear and alarm.[12][13]

The Realist

[edit]The Realist was published on a fairly regular schedule during the 1960s, then on an irregular schedule after the early 1970s. In 1966, Krassner published The Realist's controversial "Disneyland Memorial Orgy" poster, illustrated by Wally Wood (he later made this famed black-and-white poster available in a digital color version). Krassner published a red, white and blue poster that read "Fuck Communism", and enclosed copies with an issue of The Realist. He also mailed one to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover with a note that said "I hope you get a chuckle out of the enclosed patriotic poster." Krassner's hope was that he would be arrested for sending obscene material through the mail, which would allow him to get publicity for his magazine. He was disappointed when no prosecution resulted.[14]

Krassner's most notorious satire was the article "The Parts That Were Left Out of the Kennedy Book", which followed the censorship of William Manchester's 1967 book on the John F. Kennedy assassination, The Death of a President. At the climax of the grotesque-genre short-story, Lyndon B. Johnson is described as having sexually penetrated the bullet-hole wound in the throat of John F. Kennedy's corpse.[15] According to Elliot Feldman, "Some members of the mainstream press and other Washington political wonks, including Daniel Ellsberg of Pentagon Papers fame, actually believed this incident to be true."[16] In a 1995 interview for the magazine Adbusters, Krassner commented: "People across the country believed – if only for a moment – that an act of presidential necrophilia had taken place. It worked because Jackie Kennedy had created so much curiosity by censoring the book she authorized – William Manchester's The Death Of A President – because what I wrote was a metaphorical truth about LBJ's personality presented in a literary context, and because the imagery was so shocking, it broke through the notion that the war in Vietnam was being conducted by sane men."[17]

In 1966, he reprinted in The Realist an excerpt from the academic journal the Journal of the American Medical Association, but presenting it as original material. The article dealt with drinking glasses, tennis balls and other foreign bodies found in patients' rectums.[18] Some accused him of having a perverted mind, and a subscriber wrote "I found the article thoroughly repellent. I trust you know what you can do with your magazine."[18]

Krassner revived The Realist as a much smaller newsletter during the mid-1980s when material from the magazine was collected in The Best of the Realist: The 60's Most Outrageously Irreverent Magazine (Running Press, 1985). The final issue of The Realist was #146 (Spring, 2001).

Books

[edit]Krassner was a prolific writer. In 1971, he published a collection of his favorite works for The Realist, as How A Satirical Editor Became A Yippie Conspirator In Ten Easy Years.[19] In 1981 he published the satirical story Tales of Tongue Fu, in which the hilarious misadventures of the Japanese-American man Tongue Fu are mixed with a wicked social commentary. In 1994, he published his autobiography Confessions of a Raving, Unconfined Nut: Misadventures in Counter-Culture. In July 2009, City Lights Publishers released Who's to Say What's Obscene?, a collection of satirical essays that explore contemporary comedy and obscenity in politics and culture.

He published three collections of drug stories. The first collection, Pot Stories for the Soul (1999), is from other authors and is about marijuana. Psychedelic Trips for the Mind (2001), is written by Krassner himself and collects stories on LSD. The third, Magic Mushrooms and Other Highs (2004), is by Krassner too, and deals with magic mushrooms, ecstasy, peyote, mescaline, THC, opium, cocaine, ayahuasca, belladonna, ketamine, PCP, STP, "toad slime", and more.

Other activities

[edit]In 1962 Krassner published an anonymous interview with Dr Robert Spencer detailing his involvement in illegal but safe abortions.[20] Subsequent to the publication, he received calls from women asking to be put in contact with the interviewee. Krassner was later subpoenaed to appear before grand juries investigating abortion crime.

In 1965 he contributed to the Free University of New York a lecture entitled "Why the New York Times is funnier than Mad Magazine".[21] In 1968, Krassner signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.[22]

In the 1960s, Krassner was a regular contributor to several men's magazines including Cavalier and Playboy.[23] Cavalier hired Krassner for $1,000 per month to write a column called "The Naked Emperor."[24] In 1971, Krassner worked as a weekend radio personality and disk jockey at San Francisco's ABC-FM radio affiliate, KSFX, (subsequently KGO-FM). Under the pseudonym "Rumpelforeskin", he satirized culture and politics while espousing his atheism. He was also a contributor to early issues of Mad magazine. He often appeared as a stand-up comedian, and he was among those featured in the 2005 documentary The Aristocrats. Krassner was also a prolific lecturer and was a frequent speaker at both the Starwood Festival[25][26] and the WinterStar Symposium.[27][28] In 1998 he was featured at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame with Wavy Gravy during their exhibit entitled I Want to Take You Higher: The Psychedelic Era 1965–1969.[29] He was a columnist for The Nation, AVN Online and High Times. He also blogged at The Huffington Post and The Rag Blog.

Krassner wrote about the Patty Hearst trial and possible connections between the Symbionese Liberation Army and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).[30]

Krassner's legs appeared in John Lennon and Yoko Ono's 1971 film Up Your Legs Forever.[31] Singer Cass Elliot greatly admired Krassner. In a 1968 interview with Rolling Stone[32] she expressed her desire for Krassner to write the liner notes for her new solo album. "I met him with Timothy Leary," Elliott said, "and I fell instantly in love with his entire mind and body, and I would do anything for him. He's a hopeless idealist. I asked him to write my liner notes and he was delighted. He asked me what to write. I said write about the Yippies or write about anything; just write what you would like people to read, it doesn't have to do with the album."

Awards

[edit]Krassner is the only person to have won awards from both Playboy magazine (for satire) and the Feminist Party Media Workshop (for journalism). In 2000, he was given a Firecracker Alternative Book Award for High Times Presents Paul Krassner's Pot Stories for the Soul.[33] In 2001, he was the first living man to be inducted into the Counterculture Hall of Fame,[34] which took place at the Cannabis Cup in Amsterdam. He received an American Civil Liberties Union Uppie (Upton Sinclair) Award for dedication to freedom of expression, and, according to the FBI files, he was described by the FBI as "a raving, unconfined nut".[11][35] George Carlin commented: "The FBI was right, this man is dangerous – and funny; and necessary."[11] In 2005 he received a Grammy nomination for Best Album Notes for his essay on the 6-CD package Lenny Bruce: Let the Buyer Beware.

Criticism

[edit]Krassner was criticized, along with many males on the Left, in Robin Morgan's feminist manifesto, "Goodbye to All That," written in 1970:[36][37][38][39]

Goodbye to lovely "pro-Women's Liberationist" Paul Krassner, with all his astonished anger that women have lost their sense of humor "on this issue" and don't laugh any more at little funnies that degrade and hurt them: farewell to the memory of his "Instant Pussy" aerosol-can poster, to his column for the woman-hating men's magazine Cavalier, to his dream of a Rape-In against legislators' wives, to his Scapegoats and Realist Nuns and cute anecdotes about the little daughter he sees as often as any properly divorced Scarsdale middle-aged father; goodbye forever to the notion that a man is my brother who, like Paul, buys a prostitute for the night as a birthday gift for a male friend, or who, like Paul, reels off the names in alphabetical order of people in the women's movement he has fucked, reels off names in the best locker-room tradition—as proof that he's no sexist oppressor.

Personal life and death

[edit]Krassner married Jeanne Johnson in 1963[40] and had one daughter named Holly. They later divorced.[6] In 1985, Krassner moved to Venice, California where he met his wife of 32 years, artist and videographer Nancy Cain, one of the original Videofreex and founder of Camnet. They moved to Desert Hot Springs, California in 2002. Krassner suffered for several years from a neurological disease, and died on July 21, 2019, at his home in Desert Hot Springs.[41]

Writings

[edit]Books

[edit]- 1981: Tales of Tongue Fu (And/Or Press)

- 1994: Confessions of a Raving, Unconfined Nut: Misadventures in the Counter-Culture (Touchstone) ISBN 0-671-89843-4

- 2000: Sex, Drugs, and the Twinkie Murders (Loompanics Unlimited) ISBN 1-55950-206-1

- 2005: One Hand Jerking: Reports From an Investigative Satirist, Foreword by Harry Shearer, Introduction by Lewis Black (Seven Stories Press) ISBN 1-58322-696-6

Collections of drug stories

[edit]- 1999: High Times Presents Paul Krassner's Pot Stories for the Soul. Various authors. Compiled by Krassner with a foreword by Harlan Ellison (High Times) ISBN 1-893010-02-3

- 2001: Paul Krassner's Psychedelic Trips for the Mind (High Times Press) ISBN 1-893010-07-4

- 2004: Magic Mushrooms and Other Highs: From Toad Slime to Ecstasy (Ten Speed Press) ISBN 1-58008-581-4

Articles collections books

[edit]- 1961: Paul Krassner's Impolite Interviews (Lyle Stuart)

- 1971: How a Satirical Editor Became a Yippie Conspirator in Ten Easy Years (Putnam)

- 1985: The Best of the Realist: The 60's Most Outrageously Irreverent Magazine (Running Press) ISBN 0-89471-289-6

- 1996: The Winner of the Slow Bicycle Race: The Satirical Writings of Paul Krassner Introduction by Kurt Vonnegut (Seven Stories Press) ISBN 1-888363-44-4

- 2002: Murder at the Conspiracy Convention: And Other American Absurdities introduced by George Carlin (Barricade Books, Inc.) ISBN 1-56980-231-9

- 2009: Who's to Say What's Obscene? Politics, Culture and Comedy in America Today (City Lights Publishers) ISBN 978-0-87286-501-3

Articles

[edit]- "My Acid Trip with Groucho." High Times (Feb. 1981), retrieved at Sir Bacon blog.

- "Slaughtering Cows and Popping Cherries." New York Press, vol. 16, no. 34 (August 19, 2003).

- "The Trial of Vivian McPeak." High Times (February 13, 2004).

- "Steve Earl: Sticking to His Principles." High Times (May 19, 2004).

- "Lenny & the Law, Together Again." High Times (June 10, 2004).

- "The Nature of Protest: Then and Now." High Times (July 2, 2004).

- "The Blame Game." Huffington Post (August 26, 2005).

- "Life Among the Neo-Pagans." The Nation (August 29, 2005).

- "Summer of Love: 40 Years Later." San Francisco Chronicle (May 20, 2007).

- "Woody Allen Meets Tongue Fu" Archived May 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (January 11, 2008). Preface of the book Tales of Tongue Fu.

- "The Witch Hunt Ain't Over Yet." High Times (December 24, 2003).

- "Stoner Stand-ups: Pot Comics Speak Out." High Times (Oct. 2011).

Interviews

[edit]- 1999: Paul Krassner's Impolite Interviews (Seven Stories Press) ISBN 1-888363-92-4

- 2004: Sep 23, WBAI 99.5 FM New York City, Radio Unnameable: host Bob Fass interviews Paul Krassner

- 2006: RU Sirius Show #53 (7/17/2006), guest Paul Krassner (podcast, .mp3)

- 2006: Pranks! 2 Interview with Paul Krassner

- 2006: The Legacy of Timothy Leary", High Times, October 20th, 2006

- 2006: Generation on Fire: Voices of Protest from the 1960s by Jeff Kisseloff[42]

- 2007: Beatdom's Interview with Paul Krassner

- 2009: In the Jester's Court: Paul Krassner On The Virtues Of Irreverence, Indecency, And Illegal Drugs by David Kupfer (Sun Magazine Jan. 2009) Archived February 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- 2009: In Praise of Indecency: Paul Krassner Interviewed by Carol Queen (CarnalNation, July 27 2009)

- 2010: Interview With Paul Krassner from SexIs Magazine

- 2010–2011: Thorne Dreyer's three Rag Radio interviews with Paul Krassner.

- 2011: Interviewed by Marc Maron

- 2012: "Paul Krassner is Still Smokin' at 80" Interview by Jonah Raskin, The Rag Blog, June 7, 2012

Discography

[edit]Stand-up comedy recordings:

- 1996: We Have Ways of Making You Laugh (Mercury Records)

- 1997: Brain Damage Control (Mercury Records)

- 1999: Sex, Drugs and the Antichrist: Paul Krassner at MIT (Sheridan Square Entertainment)

- 2000: Campaign In the Ass (Artemis Records)

- 2002: Irony Lives (Artemis Records)

- 2004: The Zen Bastard Rides Again (Artemis Records)

Filmography

[edit]- 1972: Dynamite Chicken

- 1983: Cocaine Blues

- 1987: The Wilton North Report (TV series)

- 1990: Flashing on the Sixties: A Tribal Document

- 1998: Lenny Bruce: Swear to Tell the Truth

- 1999: The Source

- 2003: Maybe Logic: The Lives and Ideas of Robert Anton Wilson

- 2005: The Aristocrats

- 2006: Gonzo Utopia

- 2006: The U.S. vs. John Lennon

- 2006: Darryl Henriques Is in Show Business

- 2008: Sex: The Revolution (TV mini-series)

- 2008: Looking for Lenny

- 2009: Make 'Em Laugh: The Funny Business of America (PBS)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Krassner, P.; Jacobsen, S.D. (August 15, 2014). "Paul Krassner: Founder, Editor, & Contributor, The Realist". In-Sight (6.A).

- ^ a b "Paul Krassner, counterculture satirist who coined the term "Yippie," dies at 87 – Los Angeles Times". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 14, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ a b Smith, Harrison (July 22, 2019). "Paul Krassner, countercultural ringmaster and leader of the Yippies, dies at 87". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ a b "60s Activist Paul Krassner, Who Coined The Term "Yippies," Dead At 87 – CBS Los Angeles". Losangeles.cbslocal.com. July 21, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ "Recital by Violin Pupils". The New York Times. January 15, 1939.

- ^ a b "Paul Krassner, Anarchist, Prankster and a Yippies Founder, Dies at 87". The New York Times. July 22, 2019. p. A21. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Fred, Cosmopolitans: a Social and Cultural History of the Jews of the San Francisco Bay Area, University of California Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-520-25913-3.

- ^ Brian A. Pace. ""An IMC Interview with Paul Krassner" by Brian A. Pace, 06. May.2004 14:05". Portland.indymedia.org. Archived from the original on June 10, 2004. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Krassner, P: Confessions of a Raving, Unconfined Nut: Misadventures in Counter-Culture, ISBN 0-671-89843-4

- ^ Loompanics: Paul Krassner Archived July 18, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Krassner bio Archived May 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine at paulkrassner.com

- ^ The original FUCK COMMUNISM banner Ep.tc

- ^ Kurt Vonnegut's Foreword to Krassner's The Winner of the Slow Bicycle Race

- ^ The Realist Cartoons, edited by Paul Krassner, p. 9.

- ^ The Parts That Were Left Out of the Kennedy Book – The Realist, Issue No. 74 – May 1967, cover page and page 18

- ^ Paul Krassner and The Realist by Elliot Feldman

- ^ Cat Simril Interviews Paul Krassner by CAT SIMRILin from "Adbusters Quarterly" Journal of the Mental Environment (Winter 1995 Vol. 3 No. 3).

- ^ a b Here Lies Paul Krassner Archived May 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Reprinted from AIGA Journal of Graphic Design, vol.18, no. 2, 2000.

- ^ Krassner, Paul (1971). How A Satirical Editor Became A Yippie Conspirator In Ten Easy Years. Putnam.

- ^ "How the realist popped americas cherry". Nypress.com. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Ferment Magazine by Roy lisker, accessed July 16, 2012

- ^ "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" January 30, 1968 New York Post

- ^ Farber, David (1988). Chicago '68. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 25. ISBN 0-226-23800-8.

- ^ Krassner, Paul (July 16, 2019). "Paul Krassner Recalls Lenny Bruce, Cavalier Magazine 50 Years Later". Variety. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Freetimes.com

- ^ Kates, Bill (1997). Best of the Fests: Starwood Festival in High Times, 1997

- ^ Association for Consciousness Exploration. Paul Krassner Archived June 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Association for Consciousness Exploration. WinterStar Symposium 1998

- ^ "The Psychedelic Era". Archived from the original on September 5, 2007.

- ^ "Double Agent by Paul Krassner". Emptymirrorbooks.com. June 21, 1972. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Jonathan Cott (July 16, 2013). Days That I'll Remember: Spending Time With John Lennon & Yoko Ono. Omnibus Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-78323-048-8.

- ^ Jerry Hopkins (October 26, 1968). "Cass Elliot of Mamas and Papas: The Rolling Stone Interview". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ "Firecracker Alternative Book Awards". ReadersRead.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2009.

- ^ Duncan Campbell in Los Angeles (April 9, 2002). "Website". Guardian. London. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Reflections on the Art of the Put-on Archived May 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine by Michael Dooley July 3, 2007

- ^ Badley, Linda (1995). Film, Horror, and the Body Fantastic. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 106. ISBN 0-313-27523-8.

- ^ Keetley, Dawn (March 30, 2005). Public Women, Public Words: A Documentary History of American Feminism, Volume 3 (Google eBook). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-2236-9.

- ^ Lord, Catherine (May 1, 2010). "Wonder Waif Meets Super Neuter". October. 132: 135–163. doi:10.1162/octo.2010.132.1.135. S2CID 57566909.

- ^ Rodnitzky, Jerome L. (1999). Feminist Phoenix: The Rise and Fall of a Feminist Counterculture. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-96575-9.

- ^ "Close Calls : Paul Krassner". brian nation: the hot dog palace never closes. May 22, 2005. Retrieved October 29, 2023.

- ^ "1960s prankster Paul Krassner, who named Yippies, dies at 87". The Seattle Times. July 21, 2019.

- ^ Eichsteadt, James (August 2007). "Jeff Kisseloff. Generation on Fire: Voices of Protest from the 1960s--An Oral History". H-Net. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Paul Krassner at IMDb

- Art Buchwald, Barry Crimmins, Paul Krassner, Kurt Vonnegut – Beating Around the Bush: An Evening of Satire recorded on 10/06/05 at The New York Society for Ethical Culture, 63 min., mp3 format

- The Realist Archive Project at ep.tc

- The Realist website

- Hippie Museum Bio

- Excerpt from Confessions of a Raving Unconfined Nut: Misadventures in the Counter-Culture

- Articles by Paul Krassner at The Rag Blog

- Interview with Paul Krassner by Stephen McKiernan, Binghamton University Libraries Center for the Study of the 1960s, March 10, 2010

- 1932 births

- 2019 deaths

- 21st-century American essayists

- 21st-century American Jews

- 21st-century American journalists

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- American anti–Vietnam War activists

- American male essayists

- American male journalists

- American male non-fiction writers

- American psychedelic drug advocates

- American satirists

- American secular Jews

- American tax resisters

- Counterculture of the 1950s

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Counterculture of the 1970s

- HuffPost writers and columnists

- Jewish American comedians

- Jewish American journalists

- Jewish American non-fiction writers

- Kabarettists

- Mercury Records artists

- New York Press people

- People from Fire Island, New York

- People from Greenwich Village

- Writers from Brooklyn

- Yippies