Political party: Difference between revisions

Astrophobe (talk | contribs) →Party organization: first drop in the bucket of citing this section |

Astrophobe (talk | contribs) →Party organization: long-needed WP:BB overhaul of this section on party structure. Refocused the section on actually substantiated structural commonalities between countries, incorporated plenty of real references, cut far too-specific and highly WP:OR discussions of the US and Germany, and cut substantial uncited material |

||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

==Party organization== |

==Party organization== |

||

Political parties are often structured in similar ways across countries. They typically feature a single party leader, a group of party executives, and a community of party members.<ref name=helms2012/> Democracies usually select their party leadership in ways that are more open and competitive than autocracies, where the selection of a new party leader is often tightly controlled.<ref name=helms20/> In countries with large sub-national regions, particularly [[federalist]] countries, there may be regional party leaders and regional party members in addition to the national membership and leadership.<ref name = "Chhibber04"/>{{rp|75}} |

|||

===Internal structure=== |

|||

===Party leadership=== |

|||

{{More citations needed section|date=November 2020}} |

{{More citations needed section|date=November 2020}} |

||

Parties are typically led by a [[party leader]], who is the main representative of the party and often has primary responsibility for overseeing the party's policies and strategies. The leader of the party that controls the government usually becomes the [[head of government]], such as the president or prime minister, and the leaders of other parties explicitly compete to become the head of government.<ref name=helms2012>{{cite book |editor=Ludger Helms |year=2012 |title=Comparative Political Leadership |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-1-349-33368-4}}</ref> In both [[Presidential system|presidential democracies]] and [[Parliamentary system|parliamentary democracies]], the members of a party frequently have substantial input into the selection of party leaders, for example by voting on party leadership at a [[party conference]].<ref>{{cite journal |first=Michael |last=Marsh |title=Introduction: Selecting the party leader |journal=European Journal of Political Research |volume=24 |pages=229–231 |date=October 1993 |doi=10.1111/j.1475-6765.1993.tb00378.x}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=William Cross |author2=André Blais |title=Who selects the party leader? |journal=Party Politics |volume=18 |issue=2 |pages=127–150 |date=26 January 2011 |doi=10.1177/1354068810382935}}</ref> Because the leader of a major party is a powerful and visible person, many party leaders are well-known career politicians.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Stephen |last=Barber |title=Arise, Careerless Politician: The Rise of the Professional Party Leader |journal=Politics |volume=34 |issue=1 |pages=23–31 |date=17 September 2013 |doi=10.1111/1467-9256.12030}}</ref> Party leaders can be sufficiently prominent that they affect how voters perceive the entire political party,<ref>{{cite journal |first=Diego |last=Garzia |title=Party and Leader Effects in Parliamentary Elections: Towards a Reassessment |journal=Politics |volume=32 |issue=3 |pages=175–185 |date=3 September 2012 |doi=10.1111/j.1467-9256.2012.01443.x}}</ref> and some voters decide how to vote in elections partly based on how much they like the leaders of the different parties.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Jean-François Daoust |author2=André Blais |author3=Gabrielle Péloquin-Skulski |title=What do voters do when they prefer a leader from another party? |journal=Party Politics |volume=50 |pages=1103–1109 |date=29 April 2019 |doi=10.1177/1354068819845100}}</ref> |

|||

The number of people involved in choosing party leaders varies widely across parties and countries. One on extreme, party leaders might be selected from the entire electorate; on the opposite extreme, they might be selected by just one individual.<ref name=kenig09>{{cite journal |first=Ofer |last=Kenig |title=Classifying Party Leaders’ Selection Methods in Parliamentary Democracies |journal=Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties |volume=19 |issue=4 |pages=433–447 |date=30 October 2009 |doi=10.1080/17457280903275261}}</ref> Selection by a smaller group can be a feature of party leadership transitions in more autocratic countries, where the existence of political parties may be severely constrained to only one legal political party, or only one competitive party. Some of these parties, like the [[Chinese Communist Party]], have rigid methods for selecting the next party leader, which involve selection by other party members.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Li Cheng |author2=Lynn White |title=The Fifteenth Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party: Full-Fledged Technocratic Leadership with Partial Control by Jiang Zemin |journal=Asian Survey |volume=38 |issue=3 |pages=231–264 |year=1998 |doi=10.2307/2645427}}</ref> A small number of single-party states have hereditary succession, where party leadership is inherited by the child of an outgoing party leader.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Jason |last=Brownlee |title=Hereditary Succession in Modern Autocracies |journal=World Politics |volume=59 |issue=4 |pages=595–628 |date=July 2007}}</ref> Autocratic parties use more restrictive selection methods to avoid having major shifts in the regime as a result of successions.<ref name=helms20>{{cite journal |first=Ludger |last=Helms |title=Leadership succession in politics: The democracy/autocracy divide revisited |journal=The British Journal of Politics and International Relations |volume=22 |issue=2 |pages=328–346 |date=11 March 2020 |doi=10.1177/1369148120908528}}</ref> |

|||

In parliamentary democracies, on a regular, periodic basis, [[party conference]]s are held to elect party officers, although snap leadership elections can be called if enough members opt for such. Party conferences are also held in order to affirm party values for members in the coming year. American parties also meet regularly and, again, are more subordinate to elected political leaders. |

|||

===Party executives=== |

|||

Depending on the demographic spread of the party membership, party members form local or regional party committees in order to help candidates run for local or regional offices in government. These local party branches reflect the officer positions at the national level. |

|||

In both democratic and non-democratic countries, the party leader is often the foremost member of a larger party leadership. A party executive will commonly include administrative positions, like a [[party secretary]] and a [[party chair]], who may be different people from the party leader.<ref>{{cite book |first=Paul Geoffrey |last=Lewis |year=8 June 1989 |title=Political Authority and Party Secretaries in Poland, 1975-1986 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |pages=29–51 |isbn=9780521363693}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |first=John D. |last=Martz |year=1966 |title=Accion Democratica: Evolution of a Modern Political Party in Venezuela |publisher=Princeton University Press |page=155 |chapter=The Party Organization: Structural Framework |isbn=9781400875870}}</ref> These executive organizations may serve to constrain the party leader, especially if that leader is an autocrat.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Susan |last=Trevaskes |title=A Law Unto Itself: Chinese Communist Party Leadership and Yifa zhiguo in the Xi Era |journal=Modern China |volume=44 |issue=4 |pages=347–373 |date=16 April 2018 |doi=10.1177/0097700418770176}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |first=Alex M. |last=Kroeger |title=Dominant Party Rule, Elections, and Cabinet Instability in African Autocracies |journal=British Journal of Political Science |volume=50 |issue=1 |pages=79–101 |date=9 March 2018 |doi=10.1017/S0007123417000497}}</ref> It is common for political parties conduct major leadership decisions, like selecting a party executive and setting their policy goals, during regular [[party conference]]s.<ref>{{cite book |editor1=Jean-Benoit Pilet |editor2=William Cross |date=10 January 2014 |title=The Selection of Political Party Leaders in Contemporary Parliamentary Democracies: A Comparative Study |publisher=Routledge |isbn=9781317929451 <!--no page field because the point is to see that conferences are relevant across many chapters of this edited collection-->}}</ref> |

|||

Much as party leaders who are not in power are usually at least nominally competing to become the head of government, the entire party executive may be competing for various positions in the government. For example, in [[Westminster system]]s, the largest party that is out of power will form the [[Opposition (parliamentary)|Official Opposition]] in parliament, and select a [[shadow cabinet]] which (among other functions) provides a signal about which members of the party would hold which positions in the government if the party were to win an election.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Andrew C. Eggers |author2=Arthur Spirling |title=The Shadow Cabinet in Westminster Systems: Modeling Opposition Agenda Setting in the House of Commons, 1832–1915 |journal=British Journal of Political Science |volume=48 |issue=2 |pages=343–367 |date=11 April 2016 |doi=10.1017/S0007123416000016}}</ref> |

|||

It is also customary for political party members to form wings for current or prospective party members, most of which fall into the following two categories: |

|||

* identity-based: including [[youth wing]]s and/or [[Paramilitary|armed wing]]s |

|||

* position-based: including wings for candidates, mayors, governors, professionals, students, etc. The formation of these wings may have become routine but their existence is more of an indication of differences of opinion, intra-party rivalry, the influence of interest groups, or attempts to wield influence for one's state or region. |

|||

===Party membership=== |

|||

These are useful for party outreach, training, and employment. Many young aspiring politicians seek these roles and jobs as stepping stones to their political careers in legislative or executive offices. |

|||

Citizens in a democracy will often affiliate with a political party. Party membership may include paying dues, an agreement not to affiliate with multiple parties at the same time, and sometimes a statement of agreement with the party's policies and platform.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Anika |last=Gauja |title=The construction of party membership |journal=European Journal of Political Research |volume=54 |issue=2 |pages=232–248 |date=4 December 2014 |doi=10.1111/1475-6765.12078}}</ref> In democratic countries, members of political parties often are allowed to participate in elections to choose the party leadership.<ref name=kenig09/> Party members may form the base of the volunteer activists and donors who support political parties during campaigns.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Steven |last=Weldon |title=Downsize My Polity? The Impact of Size on Party Membership and Member Activism |journal=Party Politics |volume=12 |issue=4 |pages=467–481 |date=1 July 2006 |doi=10.1177/1354068806064729}}</ref> The extent of participation in party organizations can be affected by a country's political institutions, with certain [[electoral system]]s and [[party system]]s encouraging higher party membership.<ref>{{cite book |first=Alison F. |last=Smith |year=2020 |title=Political Party Membership in New Democracies |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-3030417956}}</ref> Since at least the 1980s, membership in large traditional party organizations has been steadily declining across a number of countries.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Peter Mair |author2=Ingrid van Biezen |title=Party Membership in Twenty European Democracies, 1980-2000 |journal=Party Politics |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=5–21 |date=1 January 2001 |doi=10.1177/1354068801007001001}}</ref> |

|||

The internal structure of political parties has to be democratic in some countries. In Germany Art. 21 Abs. 1 Satz 3 GG establishes a command of inner-party democracy.<ref>Cf. Brettschneider, Nutzen der ökonomischen Theorie der Politik für eine Konkretisierung des Gebotes innerparteilicher Demokratie</ref> |

|||

===International organization=== |

===International organization=== |

||

During the 19th and 20th century, many national political parties organized themselves into international organizations along similar policy lines. Notable examples are [[The Universal Party]], [[International Workingmen's Association]] (also called the First International), the [[Socialist International]] (also called the Second International), the [[Communist International]] (also called the Third International), and the [[Fourth International]], as organizations of [[working class party|working class parties]], or the [[Liberal International]] (yellow), [[Hizb ut-Tahrir]], [[Christian Democratic International]] and the [[International Democrat Union]] (blue). Organized in Italy in 1945, the [[International Communist Party]], since 1974 headquartered in Florence has sections in six countries.{{citation needed|date=February 2013}} [[Worldwide green parties]] have recently established the [[Global Greens]]. [[The Universal Party]], The Socialist International, the Liberal International, and the [[International Democrat Union]] are all based in London. |

During the 19th and 20th century, many national political parties organized themselves into international organizations along similar policy lines. Notable examples are [[The Universal Party]], [[International Workingmen's Association]] (also called the First International), the [[Socialist International]] (also called the Second International), the [[Communist International]] (also called the Third International), and the [[Fourth International]], as organizations of [[working class party|working class parties]], or the [[Liberal International]] (yellow), [[Hizb ut-Tahrir]], [[Christian Democratic International]] and the [[International Democrat Union]] (blue). Organized in Italy in 1945, the [[International Communist Party]], since 1974 headquartered in Florence has sections in six countries.{{citation needed|date=February 2013}} [[Worldwide green parties]] have recently established the [[Global Greens]]. [[The Universal Party]], The Socialist International, the Liberal International, and the [[International Democrat Union]] are all based in London. |

||

Some administrations (e.g. Hong Kong) outlaw formal linkages between local and foreign political organizations, effectively outlawing international political parties. |

Some administrations (e.g. Hong Kong) outlaw formal linkages between local and foreign political organizations, effectively outlawing international political parties. |

||

===Parliamentary parties=== |

|||

When the party is represented by members in the lower house of parliament, the party leader simultaneously serves as the leader of the [[parliamentary group]] of that full party representation; depending on a minimum number of seats held, [[Westminster system|Westminster-based]] parties typically allow for leaders to form [[frontbench]] teams of senior fellow members of the parliamentary group to serve as critics of aspects of government policy. When a party becomes the largest party not part of the Government, the party's parliamentary group forms the [[Opposition (parliamentary)|Official Opposition]], with Official Opposition frontbench team members often forming the Official Opposition [[Shadow cabinet]]. When a party achieves enough seats in an election to form a majority, the party's frontbench becomes the Cabinet of government ministers. They are all elected members. There are members who attend party without promotion. |

|||

==Regulation== |

==Regulation== |

||

Revision as of 22:38, 16 January 2021

| Part of the Politics series |

| Party politics |

|---|

|

|

In politics, a political party is an organized group of people who have the same ideology, or who otherwise have the same political positions, and who field candidates for elections, in an attempt to get them elected and thereby implement their agenda. Political parties are a defining element of representative democracy.[1]

While there is some international commonality in the way political parties are recognized and in how they operate, there are often many differences, some of which are significant. Most of political parties have an ideological core, but some do not, and many represent ideologies very different from their ideology at the time the party was founded. Many countries, such as Germany and India, have several significant political parties, and some nations have one-party systems, such as China and Cuba. The United States is in practice a two-party system but with many smaller parties also participating.

Historical development

The idea of people forming large groups or factions to advocate for their shared interests is ancient. Plato mentions the political factions of Classical Athens in the Republic,[2] and Aristotle discusses the tendency of different types of government to produce factions in the Politics.[3] Certain ancient disputes were also factional, like the Nika riots between two chariot racing factions at the Hippodrome of Constantinople. A few instances of recorded political groups or factions in history included the late Roman Republic's Populares and Optimates faction as well as the Dutch Republic's Orangists and the Staatsgezinde. However, modern political parties are considered to have emerged around the end of the 18th or early 19th centuries, appearing first in Europe and the United States.[4][5] What distinguishes political parties from factions and interest groups is that political parties use an explicit label to identify their members as having shared electoral and legislative goals.[5][6] The transformation from loose factions into organised modern political parties is considered to have first occurred in either the United Kingdom or the United States, with the United Kingdom's Conservative Party and the Democratic Party of the United States both frequently called the world's "oldest continuous political party".[7]

Emergence in Britain

The party system that emerged in early modern Britain is considered to be one of the world's first, with origins in the factions that emerged from the Exclusion Crisis and Glorious Revolution of the late 17th century.[8]: 4 The Whig faction originally organised itself around support for Protestant constitutional monarchy as opposed to absolute rule, whereas the conservative Tory faction (originally the Royalist or Cavalier faction of the English Civil War) supported a strong monarchy.[8]: 4 These two groups structured disputes in the politics of the United Kingdom throughout the 18th century. Throughout the next several centuries, these loose factions began to adopt more coherent political tendencies and ideologies: the liberal political ideas of John Locke and the notion of universal rights espoused by theorists like Algernon Sidney and later John Stuart Mill were major influences on the Whigs,[9][10] whereas the Tories eventually came to be identified with conservative philosophers like Edmund Burke.[11]

The period between the advent of factionalism, around the Glorious Revolution, and the accession of George III in 1760 was characterised by Whig supremacy, during which the Whigs remained the most powerful bloc and consistently championed constitutional monarchy with strict limits on the monarch's power, opposed the accession of a Catholic king, and believed in extending toleration to nonconformist Protestants and dissenters.[12] Although the Tories were out of office for half a century, they largely remained a united opposition to the Whigs.

When they lost power, the old Whig leadership dissolved into a decade of factional chaos with distinct Grenvillite, Bedfordite, Rockinghamite, and Chathamite factions successively in power, and all referring to themselves as "Whigs". The first distinctive political parties emerged from this chaos. The first such party was the Rockingham Whigs[13] under the leadership of Charles Watson-Wentworth and the intellectual guidance of the political philosopher Edmund Burke. Burke laid out a philosophy that described the basic framework of the political party as "a body of men united for promoting by their joint endeavours the national interest, upon some particular principle in which they are all agreed".[14] As opposed to the instability of the earlier factions, which were often tied to a particular leader and could disintegrate if removed from power, the party was centred around a set of core principles and remained out of power as a united opposition to government.[15]

A coalition including the Rockingham Whigs, led by the Earl of Shelburne, took power in 1782, only to collapse after Rockingham's death. The new government, led by the radical politician Charles James Fox in coalition with Lord North, was soon brought down and replaced by William Pitt the Younger in 1783. It was now that a genuine two-party system began to emerge, with Pitt leading the new Tories against a reconstituted "Whig" party led by Fox.[16][17] The modern Conservative Party was created out of these Pittite Tories. In 1859 under Lord Palmerston, the Whigs, heavily influenced by the classical liberal ideas of Adam Smith,[18] joined together with the free trade Tory followers of Robert Peel and the independent Radicals to form the Liberal Party.[19]

Emergence in the United States

Although the framers of the 1787 United States Constitution did not anticipate that American political disputes would be primarily organised around political parties, political controversies in the early 1790s over the extent of federal government powers saw the emergence of two proto-political parties: the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party, which were championed by Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, respectively.[20][21] However, a consensus reached on these issues ended party politics in 1816 for nearly a decade, a period commonly known as the Era of Good Feelings.[22]

The splintering of the Democratic-Republican Party in the aftermath of the contentious 1824 presidential election led to the re-emergence of political parties. Two major parties would dominate the political landscape for the next quarter-century: the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, established by Henry Clay from the National Republicans and from other Anti-Jackson groups. When the Whig Party fell apart in the mid-1850s, its position as a major U.S. political party was filled by the Republican Party.[23]

Worldwide spread

Another candidate for the first modern party system to emerge is that of Sweden.[4] Throughout the second half of the 19th century, the party model of politics was adopted across Europe. In Germany, France, Austria and elsewhere, the 1848 Revolutions sparked a wave of liberal sentiment and the formation of representative bodies and political parties. The end of the century saw the formation of large socialist parties in Europe, some conforming to the philosophy of Karl Marx, others adapting social democracy through the use of reformist and gradualist methods.[24]

At the same time, the Home Rule League Party, campaigning for Home Rule for Ireland in the British Parliament, was fundamentally changed by the Irish political leader Charles Stewart Parnell in the 1880s. In 1882, he changed his party's name to the Irish Parliamentary Party and created a well-organized grassroots structure, introducing membership to replace ad hoc informal groupings. He created a new selection procedure to ensure the professional selection of party candidates committed to taking their seats, and in 1884 he imposed a firm 'party pledge' which obliged MPs to vote as a bloc in parliament on all occasions. The creation of a strict party whip and a formal party structure was unique at the time, preceded only by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (1875), even though the latter was persecuted by Otto von Bismarck from 1878 to 1890. These parties' efficient structure and control contrasted with the loose rules and flexible informality found in the main British parties, and represented the development of new forms of party organizations, which constituted a "model" in the 20th-century.[25]

Origin of political parties

Political parties are a nearly ubiquitous feature of modern countries. Nearly all democratic countries have strong political parties, and many political scientists consider countries with fewer than two parties to necessarily be autocratic.[26][27][28] However, these sources allow that a country with multiple competitive parties is not necessarily democratic, and the politics of many autocratic countries are organised around one dominant political party.[28][29] There are many explanations for how and why political parties are such a crucial part of modern states.[5]: 11

Social cleavages

One of the core explanations for why political parties exist is that they arise from existing divisions among people. Building on Harold Hotelling's work on the aggregation of preferences and Duncan Black's development of social choice theory, Anthony Downs showed how an underlying distribution of preferences in an electorate can produce regular results in the aggregate, such as the median voter theorem.[30] This abstract model shows that parties can arise from variations within an electorate, and can adjust themselves to the patterns in the electorate (although how well the median voter idea describes the varieties of party systems that exists has been a topic of continued study).[31] However, Downs assumed that some distribution of preferences exists, rather than attributing any meaning to that distribution.

Seymour Martin Lipset and Stein Rokkan made the idea of differences within an electorate more concrete by arguing that several major party systems of the 1960s were the result of social cleavages that had already existed in the 1920s.[32] They identify four lasting cleavages in the countries they examine: a Center-Periphery cleavage regarding religion and language, a State-Church cleavage centered on control of mass education, a Land-Industry cleavage regarding freedom of industry and agricultural policies, and an Owner-Worker cleavage which includes a conflict between nationalism and internationalism.[32] Subsequent authors have expanded on or modified these cleavages, particularly when examining parties in other parts of the world.[33]

The argument that parties are produced by social cleavages has drawn several criticisms. Some authors have challenged the theory on empirical grounds, either finding no evidence for the claim that parties emerge from existing cleavages or arguing that this claim is not empirically testable.[34] Others note that while social cleavages might cause political parties to exist, this obscures the opposite effect: that political parties also cause changes in the underlying social cleavages.[5]: 13 A further objection is that, if the explanation for where parties come from is that they emerge from existing social cleavages, then the theory has not identified what causes parties unless it also explains where social cleavages come from; one response to this objection, along the lines of Charles Tilly's bellicist theory of state-building, is that social cleavages are formed by historical conflicts.[35]

Individual and group incentives

An alternative explanation for why parties are ubiquitous across the world is that the formation of parties provides compatible incentives for candidates and legislators. One explanation for the existence of parties, advanced by John Aldrich, is that the existence of political parties means that a candidate in one electoral district has an incentive to assist a candidate in a different district when those two candidates have a similar ideology.[36]

One reason that this incentive exists is that parties can solve certain legislative challenges that a legislature of unaffiliated members might face. Gary W. Cox and Mathew D. McCubbins argue that the development of many institutions can be explained by their power to constrain the incentives of individuals; a powerful institution can prohibit individuals from acting in ways that harm the community.[37] This suggests that political parties might be mechanisms for preventing candidates with similar ideologies from acting to each other's detriment.[38] One specific advantage that candidates might obtain from helping similar candidates in other districts is that the existence of a party apparatus can help coalitions of electors to agree on ideal policy choices,[39] which is in general not possible.[40][41] This could be true even in contexts where it is only slightly beneficial to be part of a party; models of how individuals coordinate on joining a group or participating in an event show how even a weak preference to be part of a group can provoke mass participation.[42]

Parties as heuristics

Parties may be necessary for many individuals to participate in politics because they provide a massively simplifying heuristic which allows people to make informed choices with a much lower cognitive cost. Without political parties, electors would have to evaluate every individual candidate in every single election they are eligible to vote in. Instead, parties enable electors to make judgments about a few groups instead of a much larger number of individuals. Angus Campbell, Philip Converse, Warren Miller, and Donald E. Stokes argued in The American Voter that identification with a political party is a crucial determinant of whether and how an individual will vote.[43] Because it is much easier to become informed about a few parties' platforms than about many candidates' personal positions, parties reduce the cognitive burden for people to cast informed votes. However, evidence suggests that over the last several decades the strength of party identification has been weakening, so this may be a less important function for parties to provide than it was in the past.[44]

Party organization

Political parties are often structured in similar ways across countries. They typically feature a single party leader, a group of party executives, and a community of party members.[45] Democracies usually select their party leadership in ways that are more open and competitive than autocracies, where the selection of a new party leader is often tightly controlled.[46] In countries with large sub-national regions, particularly federalist countries, there may be regional party leaders and regional party members in addition to the national membership and leadership.[5]: 75

Party leadership

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2020) |

Parties are typically led by a party leader, who is the main representative of the party and often has primary responsibility for overseeing the party's policies and strategies. The leader of the party that controls the government usually becomes the head of government, such as the president or prime minister, and the leaders of other parties explicitly compete to become the head of government.[45] In both presidential democracies and parliamentary democracies, the members of a party frequently have substantial input into the selection of party leaders, for example by voting on party leadership at a party conference.[47][48] Because the leader of a major party is a powerful and visible person, many party leaders are well-known career politicians.[49] Party leaders can be sufficiently prominent that they affect how voters perceive the entire political party,[50] and some voters decide how to vote in elections partly based on how much they like the leaders of the different parties.[51]

The number of people involved in choosing party leaders varies widely across parties and countries. One on extreme, party leaders might be selected from the entire electorate; on the opposite extreme, they might be selected by just one individual.[52] Selection by a smaller group can be a feature of party leadership transitions in more autocratic countries, where the existence of political parties may be severely constrained to only one legal political party, or only one competitive party. Some of these parties, like the Chinese Communist Party, have rigid methods for selecting the next party leader, which involve selection by other party members.[53] A small number of single-party states have hereditary succession, where party leadership is inherited by the child of an outgoing party leader.[54] Autocratic parties use more restrictive selection methods to avoid having major shifts in the regime as a result of successions.[46]

Party executives

In both democratic and non-democratic countries, the party leader is often the foremost member of a larger party leadership. A party executive will commonly include administrative positions, like a party secretary and a party chair, who may be different people from the party leader.[55][56] These executive organizations may serve to constrain the party leader, especially if that leader is an autocrat.[57][58] It is common for political parties conduct major leadership decisions, like selecting a party executive and setting their policy goals, during regular party conferences.[59]

Much as party leaders who are not in power are usually at least nominally competing to become the head of government, the entire party executive may be competing for various positions in the government. For example, in Westminster systems, the largest party that is out of power will form the Official Opposition in parliament, and select a shadow cabinet which (among other functions) provides a signal about which members of the party would hold which positions in the government if the party were to win an election.[60]

Party membership

Citizens in a democracy will often affiliate with a political party. Party membership may include paying dues, an agreement not to affiliate with multiple parties at the same time, and sometimes a statement of agreement with the party's policies and platform.[61] In democratic countries, members of political parties often are allowed to participate in elections to choose the party leadership.[52] Party members may form the base of the volunteer activists and donors who support political parties during campaigns.[62] The extent of participation in party organizations can be affected by a country's political institutions, with certain electoral systems and party systems encouraging higher party membership.[63] Since at least the 1980s, membership in large traditional party organizations has been steadily declining across a number of countries.[64]

International organization

During the 19th and 20th century, many national political parties organized themselves into international organizations along similar policy lines. Notable examples are The Universal Party, International Workingmen's Association (also called the First International), the Socialist International (also called the Second International), the Communist International (also called the Third International), and the Fourth International, as organizations of working class parties, or the Liberal International (yellow), Hizb ut-Tahrir, Christian Democratic International and the International Democrat Union (blue). Organized in Italy in 1945, the International Communist Party, since 1974 headquartered in Florence has sections in six countries.[citation needed] Worldwide green parties have recently established the Global Greens. The Universal Party, The Socialist International, the Liberal International, and the International Democrat Union are all based in London. Some administrations (e.g. Hong Kong) outlaw formal linkages between local and foreign political organizations, effectively outlawing international political parties.

Regulation

The freedom to form, declare membership in, or campaign for candidates from a political party is considered a measurement of a state's adherence to liberal democracy as a political value. Regulation of parties may run from a crackdown on or repression of all opposition parties, a norm for authoritarian governments, to the repression of certain parties which hold or promote ideals which run counter to the general ideology of the state's incumbents (or possess membership by-laws which are legally unenforceable).

Furthermore, in the case of far-right, far-left and regionalism parties in the national parliaments of much of the European Union, mainstream political parties may form an informal cordon sanitaire which applies a policy of non-cooperation towards those "Outsider Parties" present in the legislature which are viewed as 'anti-system' or otherwise unacceptable for government. Cordons sanitaire, however, have been increasingly abandoned over the past two decades in multi-party democracies as the pressure to construct broad coalitions in order to win elections – along with the increased willingness of outsider parties themselves to participate in government – has led to many such parties entering electoral and government coalitions.[65]

Starting in the second half of the 20th century, modern democracies have introduced rules for the flow of funds through party coffers, e.g. the Canada Election Act 1976, the PPRA in the U.K. or the FECA in the U.S. Such political finance regimes stipulate a variety of regulations for the transparency of fundraising and expenditure, limit or ban specific kinds of activity and provide public subsidies for party activity, including campaigning.

Party systems

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2020) |

Partisan style varies according to each jurisdiction, depending on how many parties there are, and how much influence each individual party has.

Nonpartisan systems

In a nonpartisan system, no official political parties exist, sometimes reflecting legal restrictions on political parties. In nonpartisan elections, each candidate is eligible for office on his or her own merits. In nonpartisan legislatures, there are no typically formal party alignments within the legislature. The administration of George Washington and the first few sessions of the United States Congress were nonpartisan. Washington also warned against political parties during his Farewell Address.[66] In the United States, the unicameral legislature of Nebraska is nonpartisan but is elected and often votes on informal party lines. In Canada, the territorial legislatures of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut are nonpartisan. In New Zealand, Tokelau has a nonpartisan parliament. Many city and county governments in the United States and Canada are nonpartisan. Nonpartisan elections and modes of governance are common outside of state institutions.[67] Unless there are legal prohibitions against political parties, factions within nonpartisan systems often evolve into political parties.

Uni-party systems

In one-party systems, one political party is legally allowed to hold effective power. Although minor parties may sometimes be allowed, they are legally required to accept the leadership of the dominant party. This party may not always be identical to the government, although sometimes positions within the party may in fact be more important than positions within the government. North Korea and China are examples; others can be found in Fascist states, such as Nazi Germany between 1934 and 1945. The one-party system is thus often equated with dictatorships and tyranny.

In dominant-party systems, opposition parties are allowed, and there may be even a deeply established democratic tradition, but other parties are widely considered to have no real chance of gaining power. Sometimes, political, social and economic circumstances and public opinion are the reason for other parties' failure. Sometimes, typically in countries with less of an established democratic tradition, it is possible the dominant party will remain in power by using patronage and sometimes by voting fraud. In the latter case, the definition between dominant and one-party system becomes rather blurred. Examples of dominant party systems include the People's Action Party in Singapore, the African National Congress in South Africa, the Cambodian People's Party in Cambodia, the Liberal Democratic Party in Japan, and the National Liberation Front in Algeria. One-party dominant system also existed in Mexico with the Institutional Revolutionary Party until the 1990s, in the southern United States with the Democratic Party from the late 19th century until the 1970s, in Indonesia with the Golkar from the early 1970s until 1998.

Bi-party systems

Two-party systems are states such as Honduras, Jamaica, Malta, Ghana and the United States in which there are two political parties dominant to such an extent that electoral success under the banner of any other party is almost impossible. One right-wing coalition party and one left-wing coalition party is the most common ideological breakdown in such a system but in two-party states, political parties are traditionally catch all parties which are ideologically broad and inclusive.

The United States has gone through several party systems, each of which has been essentially two-party in nature. The divide has typically been between a conservative and liberal party; presently, the Republican Party and Democratic Party serve these roles. Third parties have seen extremely little electoral success, and successful third party runs typically lead to vote splitting due to the first-past-the-post, winner-takes-all systems used in most US elections. There have been several examples of third parties siphoning votes from major parties, such as Theodore Roosevelt in 1912 and George Wallace in 1968, resulting in the victory of the opposing major party. In presidential elections, the Electoral College system has prevented third party candidates from being competitive, even when they have significant support (such as in 1992). More generally, parties with a broad base of support across regions or among economic and other interest groups have a greater chance of winning the necessary plurality in the U.S.'s largely single-member district, winner-take-all elections.

The UK political system, while technically a multi-party system, has functioned generally as a two-party (sometimes called a "two-and-a-half party") system; since the 1920s the two largest political parties have been the Conservative Party and the Labour Party. Before the Labour Party rose in British politics the Liberal Party was the other major political party along with the Conservatives. Though coalition and minority governments have been an occasional feature of parliamentary politics, the first-past-the-post electoral system used for general elections tends to maintain the dominance of these two parties, though each has in the past century relied upon a third party to deliver a working majority in Parliament.[68] (A plurality voting system usually leads to a two-party system, a relationship described by Maurice Duverger and known as Duverger's Law.[69]) There are also numerous other parties that hold or have held a number of seats in Parliament.

Multi-party systems

Multi-party systems are systems in which more than two parties are represented and elected to public office.

Australia, Canada, Nepal, Pakistan, India, Ireland, United Kingdom and Norway are examples of countries with two strong parties and additional smaller parties that have also obtained representation. The smaller or "third" parties may hold the balance of power in a parliamentary system, and thus may be invited to form a part of a coalition government together with one of the larger parties, or may provide a supply and confidence agreement to the government; or may instead act independently from the dominant parties.

More commonly, in cases where there are three or more parties, no one party is likely to gain power alone, and parties have to work with each other to form coalition governments. This is almost always the case in Germany on national and state level, and in most constituencies at the communal level. Furthermore, since the forming of the Republic of Iceland there has never been a government not led by a coalition, usually involving the Independence Party or the Progressive Party. A similar situation exists in the Republic of Ireland, where no one party has held power on its own since 1989. Since then, numerous coalition governments have been formed. These coalitions have been led exclusively by either Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael.

Political change is often easier with a coalition government than in one-party or two-party dominant systems.[dubious ] If factions in a two-party system are in fundamental disagreement on policy goals, or even principles, they can be slow to make policy changes, which appears to be the case now in the U.S. with power split between Democrats and Republicans. Still coalition governments struggle, sometimes for years, to change policy and often fail altogether, post World War II France and Italy being prime examples. When one party in a two-party system controls all elective branches, however, policy changes can be both swift and significant. Democrats Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson were beneficiaries of such fortuitous circumstances, as were Republicans as far removed in time as Abraham Lincoln and Ronald Reagan. Barack Obama briefly had such an advantage between 2009 and 2011.

Funding

Political parties are funded by contributions from party members and other individuals; organizations, which share their political ideas (e.g. trade union affiliation fees) or which could benefit from their activities (e.g. corporate donations); and governmental or public funding.[70]

Political parties, still called factions by some, especially those in the governmental apparatus, are lobbied vigorously by organizations, businesses and special interest groups such as trade unions. Money and gifts-in-kind to a party, or its leading members, may be offered as incentives. Such donations are the traditional source of funding for all right-of-centre cadre parties. Starting in the late 19th century these parties were opposed by the newly founded left-of-centre workers' parties. They started a new party type, the mass membership party, and a new source of political fundraising, membership dues.

From the second half of the 20th century on parties which continued to rely on donations or membership subscriptions ran into mounting problems. Along with the increased scrutiny of donations there has been a long-term decline in party memberships in most western democracies which itself places more strains on funding. For example, in the United Kingdom and Australia membership of the two main parties in 2006 is less than an 1/8 of what it was in 1950, despite significant increases in population over that period.

In some parties, such as the post-communist parties of France and Italy or the Sinn Féin party and the Socialist Party, elected representatives (i.e. incumbents) take only the average industrial wage from their salary as a representative, while the rest goes into party coffers. Although these examples may be rare nowadays, "rent-seeking" continues to be a feature of many political parties around the world.[71]

In the United Kingdom, it has been alleged that peerages have been awarded to contributors to party funds, the benefactors becoming members of the House of Lords and thus being in a position to participate in legislating. Famously, Lloyd George was found to have been selling peerages. To prevent such corruption in the future, Parliament passed the Honours (Prevention of Abuses) Act 1925 into law. Thus the outright sale of peerages and similar honours became a criminal act. However, some benefactors are alleged to have attempted to circumvent this by cloaking their contributions as loans, giving rise to the 'Cash for Peerages' scandal.

Such activities as well as assumed "influence peddling" have given rise to demands that the scale of donations should be capped. As the costs of electioneering escalate, so the demands made on party funds increase. In the UK some politicians are advocating that parties should be funded by the state; a proposition that promises to give rise to interesting debate in a country that was the first to regulate campaign expenses (in 1883).

In many other democracies such subsidies for party activity (in general or just for campaign purposes) have been introduced decades ago. Public financing for parties and/ or candidates (during election times and beyond) has several permutations and is increasingly common. Germany, Sweden, Israel, Canada, Australia, Austria and Spain are cases in point. More recently among others France, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands and Poland have followed suit.[72]

There are two broad categories of public funding, direct, which entails a monetary transfer to a party, and indirect, which includes broadcasting time on state media, use of the mail service or supplies. According to the Comparative Data from the ACE Electoral Knowledge Network, out of a sample of over 180 nations, 25% of nations provide no direct or indirect public funding, 58% provide direct public funding and 60% of nations provide indirect public funding.[73] Some countries provide both direct and indirect public funding to political parties. Funding may be equal for all parties or depend on the results of previous elections or the number of candidates participating in an election.[74] Frequently parties rely on a mix of private and public funding and are required to disclose their finances to the Election management body.[75]

In fledgling democracies funding can also be provided by foreign aid. International donors provide financing to political parties in developing countries as a means to promote democracy and good governance. Support can be purely financial or otherwise. Frequently it is provided as capacity development activities including the development of party manifestos, party constitutions and campaigning skills.[71] Developing links between ideologically linked parties is another common feature of international support for a party.[71] Sometimes this can be perceived as directly supporting the political aims of a political party, such as the support of the US government to the Georgian party behind the Rose Revolution. Other donors work on a more neutral basis, where multiple donors provide grants in countries accessible by all parties for various aims defined by the recipients.[71] There have been calls by leading development think-tanks, such as the Overseas Development Institute, to increase support to political parties as part of developing the capacity to deal with the demands of interest-driven donors to improve governance.[71]

Colors and emblems

Generally speaking, over the world, political parties associate themselves with colors, primarily for identification, especially for voter recognition during elections.

- Blue generally denotes conservatism.[76]

- Yellow is often used for liberalism or libertarianism.

- Red often signifies social democratic, socialist, or communist parties.[77][78][79]

- Green is often associated with green politics, Islamism, agrarianism, or Irish republicanism.

- Orange is the traditional color of Christian democracy and Hindu nationalism.

- Black is generally associated with fascist parties, going back to Benito Mussolini's blackshirts, but also with anarchism. Similarly, brown is sometimes associated with Nazism, going back to the Nazi Party's tan-uniformed Stormtroopers.

Color associations are useful when it is not desirable to make rigorous links to parties, particularly when coalitions and alliances are formed between political parties and other organizations, for example: "Purple" (Red-Blue) alliances, Red-green alliances, Blue-green alliances, Traffic light coalitions, Pan-green coalitions, and Pan-blue coalitions.

Political color schemes in the United States diverge from international norms. Since 2000, red has become associated with the right-wing Republican Party and blue with the left-wing Democratic Party. However, unlike political color schemes of other countries, the parties did not choose those colors; they were used in news coverage of the 2000 election results and ensuing legal battle and caught on in popular usage. Prior to the 2000 election the media typically alternated which color represented which party each presidential election cycle. The color scheme happened to get inordinate attention that year, so the cycle was stopped lest it cause confusion the following election.[80]

Emblems

The emblem of socialist parties is often a red rose held in a fist. Communist parties often use a hammer to represent the worker, a sickle to represent the farmer, or both a hammer and a sickle to refer to both at the same time.

The emblem of Nazism, the swastika has been adopted as a near-universal symbol for almost any organised white supremacist group, even though it dates from more ancient times.

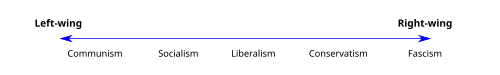

Ideology types

Klaus von Beyme categorised European parties into nine families, which described most parties. He was able to arrange seven of them from left to right: Communist, Socialist, Green, Liberal, Christian democratic, Conservative and Libertarian. The position of two other types, Agrarian and Regional/Ethnic parties varied.[81]

Organization Type

Political scientists have distinguished between different types of political parties that have evolved throughout history. These include cadre parties, mass parties, catch-all parties and cartel parties.[82] Cadre parties were political elites that were concerned with contesting elections and restricted the influence of outsiders, who were only required to assist in election campaigns. Mass parties tried to recruit new members who were a source of party income and were often expected to spread party ideology as well as assist in elections. In the United States, where both major parties were cadre parties, the introduction of primaries and other reforms has transformed them so that power is held by activists who compete over influence and nomination of candidates.[83]

Cadre party

A cadre party, or elite party, is a type of political party that was dominant in the nineteenth century before the introduction of universal suffrage and that was made up of a collection of individuals or political elites. The French political scientist Marcel Duverger first distinguished between “cadre” and “mass” parties, founding his distinction on the differences within the organisational structures of these two types.[84] Cadre parties are characterised by minimal and loose organisation, and are financed by fewer larger monetary contributions typically originating from outside the party. Cadre parties give little priority to expanding the party's membership base, and its leaders are its only members.[85][86] The earliest parties, such as the early American political parties, the Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists, are classified as cadre parties.[87]

Mass party

A mass party is a type of political party that developed around cleavages in society and mobilised the ordinary citizens or 'masses' in the political process.[87] In Europe, the introduction of universal suffrage resulted in the creation of worker's parties that later evolved into mass parties; an example is the German Social Democratic Party.[85] These parties represented large groups of citizens who had previously not been represented in political processes, articulating the interests of different groups in society. In contrast to cadre parties, mass parties are funded by their members, and rely on and maintain a large membership base. Further, mass parties prioritise the mobilisation of voters and are more centralised than cadre parties.[87][88]

Catch-all party

The catch-all party, also called the 'big tent' party, is a term developed by German-American political scientist Otto Kirchheimer used to describe the parties that developed in the 1950s and 1960s from changes within the mass parties.[89][85] Kirchheimer characterised the shift from the traditional mass parties to catch-all parties as a set of developments including the “drastic reduction of the party's ideological baggage” and the "downgrading of the role of the individual party member".[90] By broadening their central ideologies into more open-ended ones, catch-all parties seek to secure the support of a wider section of the population. Further, the role of members is reduced as catch-all parties are financed in part by the state or by donations.[91] In Europe, the shift of Christian Democratic parties that were organised around religion into broader centre-right parties epitomises this type.[92]

Cartel party

Cartel parties are a type of political party that emerged post-1970s and are characterised by heavy state financing and the diminished role of ideology as an organising principle. The cartel party thesis was developed by Richard Katz and Peter Mair who wrote that political parties have turned into "semi-state agencies",[93] acting on behalf of the state rather than groups in society. The term 'cartel' refers to the way in which prominent parties in government make it difficult for new parties to enter, as such forming a cartel of established parties. As with catch-all parties, the role of members in cartel parties is largely insignificant as parties use the resources of the state to maintain their position within the political system.[94]

Niche party

Niche parties are a type of political party that developed on the basis of the emergence of new cleavages and issues in politics, such as immigration and the environment.[95] In contrast to mainstream or catch-all parties, niche parties articulate an often limited set of interests in a way that does not conform to the dominant economic left-right divide in politics, emphasising issues that do not attain prominence within the other parties.[96] Further, niche parties do not respond to changes in public opinion to the extent that mainstream parties do. Examples of niche parties include Green parties and extreme nationalist parties, such as the Front National in France.[97] However, over time these parties may lose some of their niche qualities, instead adopting those of mainstream parties, for example after entering government.[96]

Entrepreneurial party

Entrepreneurial parties are a type of political party that is centered on a charismatic political entrepreneur.

See also

- Elite party

- Index of politics articles

- List of largest political parties

- List of political parties

- List of ruling political parties by country

- Particracy (a political regime dominated by one or more parties)

- Party class

- Party line (politics)

- UCLA School of Political Parties

References

- ^ Muirhead, Russell; Rosenblum, Nancy L. (2020). "The Political Theory of Parties and Partisanship: Catching up". Annual Review of Political Science. 23: 95–110. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041916-020727.

- ^ Plato (1935). The Republic. Macmillan and Co, Ltd.

- ^ Aristotle (1984). The Politics. The University of Chicago Press. p. 135.

- ^ a b Metcalf, Michael F. (1977). "The first "modern" party system? Political parties, Sweden's Age of liberty and the historians". Scandinavian Journal of History. 2 (1–4): 265–287. doi:10.1080/03468757708578923.

- ^ a b c d e Chhibber, Pradeep K.; Kollman, Ken (2004). The formation of national party systems: Federalism and party competition in Canada, Great Britain, India, and the United States. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Belloni, Frank P.; Beller, Dennis C. (1976). "The Study of Party Factions as Competitive Political Organizations". The Western Political Quarterly. 29 (4): 531–549. doi:10.1177/106591297602900405.

- ^ Dirr, Alison (24 October 2016). "Is the Democratic Party the oldest continuous political party in the world?". Politifact Wisconsin. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ a b Jones, J. R. (1961). The First Whigs. The Politics of the Exclusion Crisis. 1678–1683. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Ashcraft, Richard; Goldsmith, M. M. (1983). "Locke, Revolution Principles, and the Formation of Whig Ideology". Historical Journal. 26 (4): 773–800. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00012693.

- ^ Zook, Melinda S. (2002). "The Restoration Remembered: The First Whigs and the Making of their History". Seventeenth Century. 17 (2): 213–234. doi:10.1080/0268117X.2002.10555509. S2CID 153980917.

- ^ Frank O'Gorman (2003). Edmund Burke: His Political Philosophy. Routledge. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-415-32684-1.

- ^ Hamowy, Ronald (2008). "Whiggism". The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 542–43. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n328. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- ^ Robert Lloyd Kelley (1990). The Transatlantic Persuasion: The Liberal-Democratic Mind in the Age of Gladstone. Transaction Publishers. p. 83. ISBN 9781412840293.

- ^ Burke, Edmund (1770). Thoughts on the cause of the present discontents.

- ^ "ConHome op-ed: the USA, Radical Conservatism and Edmund Burke".

- ^ "The History of Political Parties in England (1678–1914)".

- ^ Parliamentary History, xxiv, 213, 222, cited in Foord, His Majesty's Opposition, 1714–1830, p. 441

- ^ Ellen Wilson and Peter Reill, Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment (2004), p. 298

- ^ Goodman, Gordon L. (1959). "Liberal unionism: The revolt of the Whigs". Victorian Studies. 3 (2): 173–189.

- ^ Hofstadter, Richard (1970). The Idea of a Party System: The Rise of Legitimate Opposition in the United States, 1780–1840. University of California Press.

- ^ William Nisbet Chambers, ed. (1972). The first party system.

- ^ Minicucci, Stephen (2004). "Internal Improvements and the Union, 1790–1860". Studies in American Political Development. 18 (2). Cambridge University Press: 160–185. doi:10.1017/S0898588X04000094.

- ^ Kollman, Ken (2012). The American political system. W. W. Norton and Company.

- ^ Busky, Donald F. (2000), Democratic Socialism: A Global Survey, Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc., p. 8,

The Frankfurt Declaration of the Socialist International, which almost all social democratic parties are members of, declares the goal of the development of democratic socialism

- ^ Jordan, Donald (1986). "John O'Connor Power, Charles Stewart Parnell and the Centralization of Popular Politics in Ireland". Irish Historical Studies. 25 (97): 46–66. doi:10.1017/S0021121400025335.

- ^ Przeworski, Adam; Alvarez, Michael E.; Cheibub, Jose Antonio; Limongi, Fernando (2000). Democracy and development: Political institutions and well-being in the world, 1950–1990. Cambridge University Press. p. 20.

- ^ Boix, Carles; Miller, Michael; Rosato, Sebastian (2013). "A complete data set of political regimes, 1800–2007". Comparative Political Studies. 46 (12): 1523–1554. doi:10.1177/0010414012463905. S2CID 45833659.

- ^ a b Svolik, Milan (2008). "Authoritarian reversals and democratic consolidation". American Political Science Review. 102 (2): 153–168. doi:10.1017/S0003055408080143.

- ^ Knutsen, Carl Henrik; Nygård, Håvard Mokleiv; Wig, Tore (2017). "Autocratic elections: Stabilizing tool or force for change?". World Politics. 69 (1): 98–143. doi:10.1017/S0043887116000149.

- ^ Downs, Anthony (1957). An economic theory of democracy. Harper Collins.

- ^ Adams, James (December 2010). "Review of Voting for Policy, Not Parties: How Voters Compensate for Power Sharing, by Orit Kedar". Perspectives on Politics. 8 (4): 1257–1258. doi:10.1017/S153759271000280X.

- ^ a b Lipset, Seymour Martin; Rokkan, Stein (1967). Cleavage structures, party systems, and voter alignments: Cross-national perspectives. New York Free Press. p. 50.

- ^ Ware, Alan (1995). Political parties and party systems. Oxford University Press. p. 22.

- ^ Lybeck, Johan A. (2017). "Is the Lipset-Rokkan Hypothesis Testable?". Scandinavian Political Studies. 8 (1–2): 105–113. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.1985.tb00314.x.

- ^ Tilly, Charles (1990). Coercion, capital, and European states. Blackwell.

- ^ Aldrich, John (1995). Why Parties?: The Origin and Transformation of Political Parties in America. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Cox, Gary; Nubbins, Mathew (1999). Legislative leviathan. University of California Press.

- ^ Hicken, Allen (2009). Building party systems in new democracies. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Tsebelis, George (2000). "Veto players and institutional analysis". Governance. 13 (4): 441–474. doi:10.1111/0952-1895.00141.

- ^ McKelvey, Richard D. (1976). "Intransitivities in multidimensional voting bodies". Journal of Economic Theory. 12: 472–482. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(76)90040-5.

- ^ Schofield, Norman (1983). "Generic instability of majority rule". Review of Economic Studies. 50 (4): 695–705. doi:10.2307/2297770. JSTOR 2297770.

- ^ Granovetter, Mark (1978). "Threshold models of collective behavior". American Journal of Sociology. 83 (6): 1420–1443. doi:10.1086/226707.

- ^ Campbell, Angus; Converse, Philip; Miller, Warren; Stokes, Donald (1960). The American Voter. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Dalton, Russell J.; Wattenberg, Martin P. (2002). Parties without partisans: Political change in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Ludger Helms, ed. (2012). Comparative Political Leadership. Springer. ISBN 978-1-349-33368-4.

- ^ a b Helms, Ludger (11 March 2020). "Leadership succession in politics: The democracy/autocracy divide revisited". The British Journal of Politics and International Relations. 22 (2): 328–346. doi:10.1177/1369148120908528.

- ^ Marsh, Michael (October 1993). "Introduction: Selecting the party leader". European Journal of Political Research. 24: 229–231. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1993.tb00378.x.

- ^ William Cross; André Blais (26 January 2011). "Who selects the party leader?". Party Politics. 18 (2): 127–150. doi:10.1177/1354068810382935.

- ^ Barber, Stephen (17 September 2013). "Arise, Careerless Politician: The Rise of the Professional Party Leader". Politics. 34 (1): 23–31. doi:10.1111/1467-9256.12030.

- ^ Garzia, Diego (3 September 2012). "Party and Leader Effects in Parliamentary Elections: Towards a Reassessment". Politics. 32 (3): 175–185. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9256.2012.01443.x.

- ^ Jean-François Daoust; André Blais; Gabrielle Péloquin-Skulski (29 April 2019). "What do voters do when they prefer a leader from another party?". Party Politics. 50: 1103–1109. doi:10.1177/1354068819845100.

- ^ a b Kenig, Ofer (30 October 2009). "Classifying Party Leaders' Selection Methods in Parliamentary Democracies". Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. 19 (4): 433–447. doi:10.1080/17457280903275261.

- ^ Li Cheng; Lynn White (1998). "The Fifteenth Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party: Full-Fledged Technocratic Leadership with Partial Control by Jiang Zemin". Asian Survey. 38 (3): 231–264. doi:10.2307/2645427.

- ^ Brownlee, Jason (July 2007). "Hereditary Succession in Modern Autocracies". World Politics. 59 (4): 595–628.

- ^ Lewis, Paul Geoffrey (8 June 1989). Political Authority and Party Secretaries in Poland, 1975-1986. Cambridge University Press. pp. 29–51. ISBN 9780521363693.

- ^ Martz, John D. (1966). "The Party Organization: Structural Framework". Accion Democratica: Evolution of a Modern Political Party in Venezuela. Princeton University Press. p. 155. ISBN 9781400875870.

- ^ Trevaskes, Susan (16 April 2018). "A Law Unto Itself: Chinese Communist Party Leadership and Yifa zhiguo in the Xi Era". Modern China. 44 (4): 347–373. doi:10.1177/0097700418770176.

- ^ Kroeger, Alex M. (9 March 2018). "Dominant Party Rule, Elections, and Cabinet Instability in African Autocracies". British Journal of Political Science. 50 (1): 79–101. doi:10.1017/S0007123417000497.

- ^ Jean-Benoit Pilet; William Cross, eds. (10 January 2014). The Selection of Political Party Leaders in Contemporary Parliamentary Democracies: A Comparative Study. Routledge. ISBN 9781317929451.

- ^ Andrew C. Eggers; Arthur Spirling (11 April 2016). "The Shadow Cabinet in Westminster Systems: Modeling Opposition Agenda Setting in the House of Commons, 1832–1915". British Journal of Political Science. 48 (2): 343–367. doi:10.1017/S0007123416000016.

- ^ Gauja, Anika (4 December 2014). "The construction of party membership". European Journal of Political Research. 54 (2): 232–248. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12078.

- ^ Weldon, Steven (1 July 2006). "Downsize My Polity? The Impact of Size on Party Membership and Member Activism". Party Politics. 12 (4): 467–481. doi:10.1177/1354068806064729.

- ^ Smith, Alison F. (2020). Political Party Membership in New Democracies. Springer. ISBN 978-3030417956.

- ^ Peter Mair; Ingrid van Biezen (1 January 2001). "Party Membership in Twenty European Democracies, 1980-2000". Party Politics. 7 (1): 5–21. doi:10.1177/1354068801007001001.

- ^ McDonnell, Duncan and Newell, James (2011) 'Outsider Parties'.

- ^ Redding 2004

- ^ Abizadeh 2005.

- ^ "General Election results through time, 1945–2001". BBC News. Retrieved 19 May 2006.

- ^ Duverger 1954

- ^ See Heard, Alexander, 'Political financing'. In: Sills, David I. (ed.) International Emcyclopedia of the Social Sciences, vol. 12. New York: Free Press – Macmillan, 1968, pp. 235–41; Paltiel, Khayyam Z., 'Campaign finance – contrasting practices and reforms'. In: Butler, David et al. (eds.), Democracy at the polls – a comparative study of competitive national elections. Washington, D.C.: AEI, 1981, pp. 138–72; Paltiel, Khayyam Z., 'Political finance'. In: Bogdanor, Vernon (ed.), The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Political Institutions. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1987, pp. 454–56; 'Party finance', in: Kurian, George T. et al. (eds.) The encyclopedia of political science. vol 4, Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2011, pp. 1187–89.

- ^ a b c d e Foresti and Wild 2010. Support to political parties: a missing piece of the governance puzzle. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ For details you may want to consult specific articles on Campaign finance in the United States, Federal political financing in Canada, Party finance in Germany, Political donations in Australia, Political finance, Political funding in Japan, Political funding in the United Kingdom.

- ^ ACEproject.org ACE Electoral Knowledge Network: Comparative Data: Political Parties and Candidates

- ^ ACEproject.org ACE Electoral Knowledge Network: Comparative Data: Political Parties and Candidates

- ^ ACEproject.org ACE Encyclopaedia: Public funding of political parties

- ^ Why is the Conservative Party Blue, BBC, 20 April 2006

- ^ Adams, Sean; Morioka, Noreen; Stone, Terry Lee (2006). Color Design Workbook: A Real World Guide to Using Color in Graphic Design. Gloucester, Mass.: Rockport Publishers. pp. 86. ISBN 159253192X. OCLC 60393965.

- ^ Kumar, Rohit Vishal; Joshi, Radhika (October–December 2006). "Colour, Colour Everywhere: In Marketing Too". SCMS Journal of Indian Management. 3 (4): 40–46. ISSN 0973-3167. SSRN 969272.

- ^ Cassel-Picot, Muriel "The Liberal Democrats and the Green Cause: From Yellow to Green" in Leydier, Gilles and Martin, Alexia (2013) Environmental Issues in Political Discourse in Britain and Ireland. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p.105. ISBN 9781443852838

- ^ Farhi, Paul (2 November 2004), "Elephants Are Red, Donkeys Are Blue", The Washington Post

- ^ Ware, Political parties, p. 22

- ^ Schumacher, Gijs (2017). ‘The Transformation of Political Parties’, in van Praag, Philip (ed.), Political Science and Changing Politics. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp.163-178

- ^ Ware, Political parties, pp. 65–67

- ^ Duverger, Maurice (1964). Political Parties: Their Organisation and Activity in the Modern State (3 ed.). London: Methuen. pp. 60–71.

- ^ a b c Schumacher, Gijs (2017). ‘The Transformation of Political Parties’, in van Praag, Philip (ed.), Political Science and Changing Politics. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp.163-178 (p.165)

- ^ Katz, Richard S.; Mair, Peter (1995). "Changing Models of Party Organisation and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party". Party Politics. 1 (1): 20. doi:10.1177/1354068895001001001.

- ^ a b c Hague, Rod; McCormick, John; Harrop, Martin (2019). Comparative Government and Politics, An Introduction (11 ed.). Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 271.

- ^ Angell, Harold M. (June 1987). "Duverger, Epstein and the Problem of the Mass Party: The Case of the Parti Québécois". Canadian Journal of Political Science. 20 (2): 364. doi:10.1017/S0008423900049489.

- ^ Krouwel, Andre (2003). "Otto Kirchheimer and the Catch-All Party". West European Politics. 26 (2): 24. doi:10.1080/01402380512331341091. S2CID 145308222.

- ^ Kirchheimer, Otto (1966). 'The Transformation of Western European Party Systems', in J. LaPalombara and M. Weiner (eds.), Political Parties and Political Development. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, pp.177–200 (p.190)

- ^ Schumacher, Gijs (2017). 'The Transformation of Political Parties', in van Praag, Philip (ed.), Political Science and Changing Politics. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp.163-178 (p.167)

- ^ Hague, Rod; McCormick, John; Harrop, Martin (2019). Comparative Government and Politics, An Introduction (11 ed.). Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 272.

- ^ Katz, Richard S.; Mair, Peter (1995). "Changing Models of Party Organisation and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party". Party Politics. 1 (1): 16. doi:10.1177/1354068895001001001.

- ^ Schumacher, Gijs (2017). 'The Transformation of Political Parties', in van Praag, Philip (ed.), Political Science and Changing Politics. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp.163-178 (p.168)

- ^ Meguid, Bonnie M. (2005). "Competition Between Unequals: The Role of Mainstream Party Strategy in Niche Party Success". American Political Science Review. 99 (3): 347–348. doi:10.1017/S0003055405051701.

- ^ a b Meyer, Thomas; Miller, Bernhard (2015). "The niche party concept and its measurement". Party Politics. 21 (2): 259–271. doi:10.1177/1354068812472582. PMC 5180693. PMID 28066152.

- ^ Adams, James; Clark, Michael; Ezrow, Lawrence; Glasgow, Garrett (2006). "Are Niche Parties Fundamentally Different from Mainstream Parties? The Causes and the Electoral Consequences of Western European Parties' Policy Shifts, 1976-1998" (PDF). American Journal of Political Science. 50 (3): 513–529. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00199.x.

External links

- Party Facts: A database of political parties worldwide

- U.S. Party Platforms from 1840 to 2004 at The American Presidency Project: UC Santa Barbara

- Political resources on the net

- Political Party Paradox by Elmer G. Wiens