Sustainable consumption: Difference between revisions

m added wiki links |

updated with 3 items from 2022 in science, 3 items from 2021 in science and 2 items from 2020 in science (→Consumption shifting: ), expanded (incl with content from Free-ranging dog, Climate change mitigation, Carbon leakage and Climate justice) |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

==The Oslo definition== |

==The Oslo definition== |

||

In 1994 the [[Oslo Symposium|Oslo symposium]] defined sustainable consumption as the consumption of goods and services that enhance quality of life while limiting the use of [[Natural resource|natural resources]] and noxious materials.<ref name=":2">Source: Norwegian Ministry of the Environment (1994) Oslo Roundtable on Sustainable Production and Consumption.</ref> |

In 1994 the [[Oslo Symposium|Oslo symposium]] defined sustainable consumption as the consumption of goods and services that enhance quality of life while limiting the use of [[Natural resource|natural resources]] and noxious materials.<ref name=":2">Source: Norwegian Ministry of the Environment (1994) Oslo Roundtable on Sustainable Production and Consumption.</ref> |

||

== Consumption shifting == |

|||

{{See also|Sustainable products}} |

|||

Studies found that [[systemic change]] for "decarbonization" of humanity's economic structures<ref name="effectspaper">{{cite journal |last1=Forster |first1=Piers M. |last2=Forster |first2=Harriet I. |last3=Evans |first3=Mat J. |last4=Gidden |first4=Matthew J. |last5=Jones |first5=Chris D. |last6=Keller |first6=Christoph A. |last7=Lamboll |first7=Robin D. |last8=Quéré |first8=Corinne Le |last9=Rogelj |first9=Joeri |last10=Rosen |first10=Deborah |last11=Schleussner |first11=Carl-Friedrich |last12=Richardson |first12=Thomas B. |last13=Smith |first13=Christopher J. |last14=Turnock |first14=Steven T. |title=Current and future global climate impacts resulting from COVID-19 |journal=Nature Climate Change |date=7 August 2020 |volume=10 |issue=10 |pages=913–919 |doi=10.1038/s41558-020-0883-0 |bibcode=2020NatCC..10..913F |s2cid=221019148 |language=en |issn=1758-6798|doi-access=free }}</ref> or [[Structural fix|root-cause system changes]] above politics are required<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ripple |first1=William J. |last2=Wolf |first2=Christopher |last3=Newsome |first3=Thomas M. |last4=Gregg |first4=Jillian W. |last5=Lenton |first5=Timothy M. |last6=Palomo |first6=Ignacio |last7=Eikelboom |first7=Jasper A. J. |last8=Law |first8=Beverly E. |last9=Huq |first9=Saleemul |last10=Duffy |first10=Philip B. |last11=Rockström |first11=Johan |display-authors=4 |title=World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency 2021 |journal=BioScience |date=28 July 2021 |volume=71 |issue=9 |page=biab079 |doi=10.1093/biosci/biab079 |url=https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/advance-article/doi/10.1093/biosci/biab079/6325731 |hdl=1808/30278 |hdl-access=free |access-date=26 August 2021 |archive-date=26 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210826155112/https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/advance-article/doi/10.1093/biosci/biab079/6325731 |url-status=live }}</ref> for a [[mitigation of climate change|substantial impact on global warming]]. Such changes may result in [[sustainable lifestyle]]s, along with associated products, services and expenditures,<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kanyama |first1=Annika Carlsson |last2=Nässén |first2=Jonas |last3=Benders |first3=René |title=Shifting expenditure on food, holidays, and furnishings could lower greenhouse gas emissions by almost 40% |journal=Journal of Industrial Ecology |year=2021 |volume=25 |issue=6 |pages=1602–1616 |doi=10.1111/jiec.13176 |language=en |issn=1530-9290|doi-access=free }}</ref> being structurally supported and becoming sufficiently prevalent and effective in terms of collective greenhouse gas emission reductions. |

|||

Nevertheless, [[ethical consumerism]] usually only refers to individual choices, and not the consumption behavior and/or import and consumption policies by the decision-making of [[nation]]-states. These have however been compared for [[List of countries by vehicles per capita|road vehicles]] and [[List of countries by meat consumption|meat consumption]] per capita as well as by [[overconsumption]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Country Overshoot Days 2022 |url=https://www.overshootday.org/newsroom/country-overshoot-days/ |website=Earth Overshoot Day |access-date=26 May 2022}}</ref> |

|||

[[Life-cycle assessment]]s could assess the comparative sustainability and overall environmental impacts of products – including (but not limited to): "raw materials, extraction, processing and transport; manufacturing; delivery and installation; customer use; and end of life (such as disposal or recycling)".<ref name="Arratia"/> |

|||

=== Sustainable food consumption === |

|||

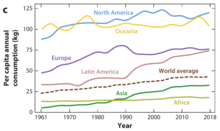

[[File:Per capita annual meat consumption by region.png|thumb|Per capita annual meat consumption by region<ref name="10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-032340"/>]] |

|||

[[File:Average greenhouse gas emissions associated with different food products.png|thumb|Average greenhouse gas emissions by food product<ref name="10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-032340"/>]] |

|||

[[File:Amazon Rainforest, Brazil Timelapse 1984-2018.gif|thumb|350px|Non-intervention in processes related to beef production via policies may be a main driver of tropical deforestation.]] |

|||

The [[environmental impact of meat production]] (and dairy) are large: raising animals for human consumption accounts for approximately 40% of the total amount of agricultural output in industrialized countries. Grazing occupies 26% of the earth's ice-free terrestrial surface, and feed crop production uses about one third of all arable land.<ref name=Steinfeld2006>{{Citation |last1= Steinfeld|first1= Henning|last2= Gerber|first2= Pierre|last3= Wassenaar|first3= Tom|last4= Castel|first4= Vincent|last5= Rosales|first5= Mauricio|last6= de Haan|first6= Cees|year= 2006|title= Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options|publisher= FAO|location= Rome|url=http://www.europarl.europa.eu/climatechange/doc/FAO%20report%20executive%20summary.pdf }}</ref> A global food [[Emission inventory|emissions database]] shows that [[food system]]s are responsible for one third of the global anthropogenic [[Greenhouse gas emissions|GHG emissions]].<ref>{{cite news ||title=FAO – News Article: Food systems account for more than one third of global greenhouse gas emissions |url=http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/1379373/icode/ |access-date=22 April 2021 |work=www.fao.org |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal ||last1=Crippa |first1=M. |last2=Solazzo |first2=E. |last3=Guizzardi |first3=D. |last4=Monforti-Ferrario |first4=F. |last5=Tubiello |first5=F. N. |last6=Leip |first6=A. |title=Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions |journal=Nature Food |date=March 2021 |volume=2 |issue=3 |pages=198–209 |doi=10.1038/s43016-021-00225-9 |language=en |issn=2662-1355|doi-access=free }}</ref> Moreover, there can be competition for resources, such as land, between growing crops for human consumption and growing crops for animals, also referred to as "[[food vs. feed]]" (see also: [[food security]]).<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Manceron|first=Stéphane|last2=Ben-Ari|first2=Tamara|last3=Dumas|first3=Patrice|date=July 2014|title=Feeding proteins to livestock: Global land use and food vs. feed competition|url=http://www.ocl-journal.org/10.1051/ocl/2014020|journal=OCL|volume=21|issue=4|pages=D408|doi=10.1051/ocl/2014020|issn=2272-6977|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Steinfeld|first=H.|last2=Opio|first2=C.|date=2010|title=The availability of feeds for livestock: Competition with human consumption in present world|url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/B7D5D3D44F757822AEE2C75F01D046B7/S2040470010000488a.pdf/the-availability-of-feeds-for-livestock-competition-with-human-consumption-in-present-world.pdf|journal=Advances in Animal Biosciences|language=en|volume=1|issue=2|pages=421|doi=10.1017/S2040470010000488|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

Therefore, sustainable consumption also includes food consumption – shifting such to [[sustainable diet]]s. |

|||

[[Novel food]]s such as under-development<ref>{{cite web |title=Lebensmittel aus dem Labor könnten der Umwelt helfen |url=https://www.sciencemediacenter.de/alle-angebote/research-in-context/details/news/lebensmittel-aus-dem-labor-koennten-der-umwelt-helfen/ |website=www.sciencemediacenter.de |access-date=16 May 2022 |language=en}}</ref> [[cultured meat]] and [[Cellular agriculture#Dairy|dairy]], existing small-scale [[Microbial food cultures|microbial foods]] and [[Insects as food|ground-up insects]] (see also: [[pet food]] and [[animal feed]]) are shown to have the potential to [[sustainable food|reduce environmental impacts]] by over 80% in a study.<ref>{{cite web |title=Lab-grown meat and insects 'good for planet and health' |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-61182294 |website=BBC News|date=25 April 2022 |access-date=25 April 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Incorporation of novel foods in European diets can reduce global warming potential, water use and land use by over 80% |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-022-00489-9 |website=Nature Food|date=25 April 2022 |access-date=25 April 2022}}</ref> Many studies such as a 2022 [[scientific review|review]] about meat and sustainability of food systems, animal welfare, and healthy nutrition concluded that meat consumption has to be reduced substantially for sustainable consumption. The review names broad potential measures such as "restrictions or fiscal mechanisms".<ref>{{cite news |title=Meat consumption must fall by at least 75% for sustainable consumption, says study |url=https://phys.org/news/2022-04-meat-consumption-fall-sustainable.html |access-date=12 May 2022 |work=[[University of Bonn]]}}</ref><ref name="10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-032340">{{cite journal |last1=Parlasca |first1=Martin C. |last2=Qaim |first2=Matin |title=Meat Consumption and Sustainability |journal=Annual Review of Resource Economics |date=5 October 2022 |volume=14 |doi=10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-032340 |url=https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-032340 |issn=1941-1340}}</ref> |

|||

A considerable proportion of consumers of food produced by the food system may be non-livestock animals such as pet-dogs: the global [[dog]] population is estimated to be 900 million,<ref name=gompper2013>{{cite book |last=Gompper |first=Matthew E. |year=2013 |chapter=The dog–human–wildlife interface: assessing the scope of the problem |title=Free-Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation |editor-last=Gompper |editor-first=Matthew E. |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0191810183 |pages=9–54}}</ref><ref name=lescureaux2014>{{cite journal|doi=10.1016/j.biocon.2014.01.032|title=Warring brothers: The complex interactions between wolves (Canis lupus) and dogs (Canis familiaris) in a conservation context|journal=Biological Conservation|volume=171|pages=232–245|year=2014|last1=Lescureux|first1=Nicolas|last2=Linnell|first2=John D.C.}}</ref>{{update inline|date=May 2022}} of which around 20% are regarded as owned pets.<ref name=Lord2013>{{cite journal|doi= 10.1016/j.beproc.2012.10.009|title= Variation in reproductive traits of members of the genus Canis with special attention to the domestic dog (Canis familiaris)|year= 2013|last1= Lord|first1= Kathryn|last2= Feinstein|first2= Mark|last3= Smith|first3= Bradley|last4= Coppinger|first4= Raymond|journal= Behavioural Processes|volume= 92|pages= 131–142|pmid= 23124015}}</ref>{{update inline|date=May 2022}} |

|||

===Product labels=== |

|||

{{Excerpt|Label|Environmental considerations}} |

|||

The app [[Code Check]] gives versed smartphone users some capability to scan ingredients in food, drinks and cosmetics for filtering out some of the products that are legal but nevertheless unhealthy or unsustainable from their consumption/purchases.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Mulka |first1=Angela |title=Apps for Earth Day: 5 options to keep your green goals |url=https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Earth-Day-apps-eco-conscious-apps-17108115.php |website=SFGATE |access-date=26 May 2022 |date=21 April 2022}}</ref> A similar "personal shopping assistant" has been investigated in a study.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Asikis |first1=Thomas |last2=Klinglmayr |first2=Johannes |last3=Helbing |first3=Dirk |last4=Pournaras |first4=Evangelos |title=How value-sensitive design can empower sustainable consumption |journal=Royal Society Open Science |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=201418 |doi=10.1098/rsos.201418}}</ref> Studies indicated a low level of use of sustainability labels on food.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Grunert |first1=Klaus G. |last2=Hieke |first2=Sophie |last3=Wills |first3=Josephine |title=Sustainability labels on food products: Consumer motivation, understanding and use |journal=Food Policy |date=1 February 2014 |volume=44 |pages=177–189 |doi=10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.12.001 |language=en |issn=0306-9192}}</ref> Moreover, existing labels have been intensely criticized for invalidity or unreliability, often amounting to [[greenwashing]] or being ineffective.<ref name="Arratia">{{cite news |last1=Arratia |first1=Ramon |title=Full product transparency gives consumers more informed choices |url=https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/blog/full-product-transparency-life-cycle-consumers |access-date=26 May 2022 |work=The Guardian |date=18 December 2012 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Certification schemes such as FSC are greenwashing forest destruction |url=https://www.greenpeace.org/africa/en/press/13254/certification-schemes-such-as-fsc-are-greenwashing-forest-destruction/ |access-date=26 May 2022 |work=Greenpeace Africa |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Cazzolla Gatti |first1=Roberto |last2=Velichevskaya |first2=Alena |journal=Science of the Total Environment |date=10 November 2020 |volume=742 |pages=140712 |doi=10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140712 |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969720342340|title=Certified "sustainable" palm oil took the place of endangered Bornean and Sumatran large mammals habitat and tropical forests in the last 30 years |pmid=32721759 |bibcode=2020ScTEn.742n0712C |s2cid=220852123 |access-date=16 August 2020 |language=en |issn=0048-9697}}</ref> |

|||

===Product information transparency and trade control=== |

|||

{{Further|Produce traceability|Emission intensity#Estimating emissions|Standardization#Environmental protection}} |

|||

[[File:Comparison of footprint-based and transboundary pollution-based relationships among G20 nations for the number of PM2.5-related premature deaths.webp|thumb|300px|Comparison of footprint-based and transboundary pollution-based relationships among G20 nations for the number of PM<sub>2.5</sub>-related premature deaths.<ref name="10.1038/s41467-021-26348-y"/>]] |

|||

If information is linked to products e.g. via a digital product passport, along with proper architecture and governance for data sharing and data protection, it could help achieve climate neutrality and foster [[Dematerialization (economics)|dematarialisation]].<ref>{{cite web |title=https://www.epc.eu/en/events/Digitalisation-for-a-circular-economy-A-driver~30dbd0 |url=https://www.epc.eu/en/events/Digitalisation-for-a-circular-economy-A-driver~30dbd0 |website=www.epc.eu |access-date=26 May 2022}}</ref> In the EU, a [[Digital Product Passport]] is being developed. When there is an increase in [[greenhouse gas emissions]] in one country as a result of an [[emissions reduction]] by a second country with a strict climate policy this is referred to as [[carbon leakage]].<ref>{{citation |title=Emissions Loophole Stays Open in E.U. |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/19/business/energy-environment/emissions-loophole-stays-open-in-eu.html |accessdate=1 April 2015 |author=Andrés Cala |work=The New York Times |date=18 November 2014}}</ref> In the EU, the proposed [[Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism]] could help mitigate this problem,<ref>{{cite news |last1=Abnett |first1=Kate |title=EU countries support plan for world-first carbon border tariff |url=https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/eu-countries-back-plan-world-first-carbon-border-tariff-2022-03-15/ |access-date=26 May 2022 |work=Reuters |date=16 March 2022 |language=en}}</ref> and possibly increase the capacity to account for imported pollution/harm/death-footprints. Footprints of nondomestic production are significant: for instance, a study concluded that PM<sub>2.5</sub> [[air pollution]] induced by the contemporary free [[international trade|trade]] and consumption by the {{Hover title|the EU as a whole (not a nation) is not included here|19}} [[G20]] nations causes two million premature deaths annually, suggesting that the average lifetime consumption of about ~28 people in these countries causes at least one premature death (average age ~67) while developing countries "cannot be expected" to implement or be able to implement countermeasures without external support or internationally coordinated efforts.<ref>{{cite news |title=Air pollution from G20 consumers caused two million deaths in 2010 |url=https://www.newscientist.com/article/2295873-air-pollution-from-g20-consumers-caused-two-million-deaths-in-2010/ |access-date=11 December 2021 |work=New Scientist}}</ref><ref name="10.1038/s41467-021-26348-y">{{cite journal |last1=Nansai |first1=Keisuke |last2=Tohno |first2=Susumu |last3=Chatani |first3=Satoru |last4=Kanemoto |first4=Keiichiro |last5=Kagawa |first5=Shigemi |last6=Kondo |first6=Yasushi |last7=Takayanagi |first7=Wataru |last8=Lenzen |first8=Manfred |title=Consumption in the G20 nations causes particulate air pollution resulting in two million premature deaths annually |journal=Nature Communications |date=2 November 2021 |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=6286 |doi=10.1038/s41467-021-26348-y |pmid=34728619 |pmc=8563796 |bibcode=2021NatCo..12.6286N |language=en |issn=2041-1723}}</ref> |

|||

[[Supply chain sustainability|Transparency of supply chains]] is important for global goals<ref name="10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.025">{{cite journal |last1=Gardner |first1=T. A. |last2=Benzie |first2=M. |last3=Börner |first3=J. |last4=Dawkins |first4=E. |last5=Fick |first5=S. |last6=Garrett |first6=R. |last7=Godar |first7=J. |last8=Grimard |first8=A. |last9=Lake |first9=S. |last10=Larsen |first10=R. K. |last11=Mardas |first11=N. |last12=McDermott |first12=C. L. |last13=Meyfroidt |first13=P. |last14=Osbeck |first14=M. |last15=Persson |first15=M. |last16=Sembres |first16=T. |last17=Suavet |first17=C. |last18=Strassburg |first18=B. |last19=Trevisan |first19=A. |last20=West |first20=C. |last21=Wolvekamp |first21=P. |title=Transparency and sustainability in global commodity supply chains |journal=World Development |date=1 September 2019 |volume=121 |pages=163–177 |doi=10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.025 |language=en |issn=0305-750X}}</ref> such as ending net-[[deforestation]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Nepstad |first1=Daniel |last2=McGrath |first2=David |last3=Stickler |first3=Claudia |last4=Alencar |first4=Ane |last5=Azevedo |first5=Andrea |last6=Swette |first6=Briana |last7=Bezerra |first7=Tathiana |last8=DiGiano |first8=Maria |last9=Shimada |first9=João |last10=Seroa da Motta |first10=Ronaldo |last11=Armijo |first11=Eric |last12=Castello |first12=Leandro |last13=Brando |first13=Paulo |last14=Hansen |first14=Matt C. |last15=McGrath-Horn |first15=Max |last16=Carvalho |first16=Oswaldo |last17=Hess |first17=Laura |title=Slowing Amazon deforestation through public policy and interventions in beef and soy supply chains |journal=Science |date=6 June 2014 |volume=344 |issue=6188 |pages=1118–1123 |doi=10.1126/science.1248525|pmid=24904156 |bibcode=2014Sci...344.1118N |s2cid=206553761 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Nolte |first1=Christoph |last2=le Polain de Waroux |first2=Yann |last3=Munger |first3=Jacob |last4=Reis |first4=Tiago N. P. |last5=Lambin |first5=Eric F. |title=Conditions influencing the adoption of effective anti-deforestation policies in South America's commodity frontiers |journal=Global Environmental Change |date=1 March 2017 |volume=43 |pages=1–14 |doi=10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.01.001 |language=en |issn=0959-3780}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=McAlpine |first1=C. A. |last2=Etter |first2=A. |last3=Fearnside |first3=P. M. |last4=Seabrook |first4=L. |last5=Laurance |first5=W. F. |title=Increasing world consumption of beef as a driver of regional and global change: A call for policy action based on evidence from Queensland (Australia), Colombia and Brazil |journal=Global Environmental Change |date=1 February 2009 |volume=19 |issue=1 |pages=21–33 |doi=10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.008 |language=en |issn=0959-3780|url=https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/79486 }}</ref><ref name="10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.025"/> [[Policy]]-options for reducing imported deforestation also include "Lower/raise import tariffs for sustainably/unsustainably produced commodities" and "Regulate imports, e.g., through quotas, bans, or preferential access agreements".<ref name="10.1016/j.oneear.2021.01.011">{{cite journal |last1=Bager |first1=Simon L. |last2=Persson |first2=U. Martin |last3=Reis |first3=Tiago N. P. dos |title=Eighty-six EU policy options for reducing imported deforestation |journal=One Earth |date=19 February 2021 |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=289–306 |doi=10.1016/j.oneear.2021.01.011 |language=English |issn=2590-3330}}</ref> However, several [[theory of change|theories of change]] of policy options rely on (true / reliable) information being available/provided to "shift demand—both intermediate and final—either away from imported [forest-risk commodities (FRC)] completely, e.g., through diet shifts (IC1), or to sustainably produced FRCs, e.g., through voluntary or mandatory supply-chain transparency (IS1, RS2)."<ref name="10.1016/j.oneear.2021.01.011"/> |

|||

As of 2021, one approach under development is binary "labelling" of investments as [[EU taxonomy for sustainable activities|"green" according to an EU governmental body-created "taxonomy"]] for voluntarily financial investment redirection/guidance based on this categorization.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Abnett |first1=Kate |title=EU passes first chunk of green investment rules, contentious sectors still to come |url=https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/eu-passes-first-chunk-green-investment-rules-contentious-sectors-still-come-2021-12-09/ |access-date=24 March 2022 |work=Reuters |date=9 December 2021 |language=en}}</ref> The company Dayrize attempts to accurately assess environmental and social impacts of consumer products.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Latch Teams With SunCorp To Launch New Storefront To Help Shoppers Make Sustainable Choices |url=https://www.bandt.com.au/the-latch-teams-with-suncorp-to-launch-new-storefront-to-help-shoppers-make-sustainable-choices/ |website=B&T |access-date=26 May 2022 |date=3 May 2022}}</ref> |

|||

Reliable evaluations and categorizations of products may enable measures such as policy-combinations that include transparent criteria-based [[eco-tariff]]s, bans ([[import control]]), support of selected production and subsidies which shifts, rather than mainly reduces, consumption. International sanctions during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine [[International sanctions during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine#Oil|included restrictions on Russian fossil fuel imports]] while supporting alternatives, albeit these sanctions were not based on environment-related qualitative criteria of the products. |

|||

=== Fairness and income/spending freedoms === |

|||

The bottom half of the population is directly-responsible for less than 20% of energy footprints and consume less than the top 5% in terms of trade-corrected energy. High-income individuals usually have higher [[carbon footprint|energy footprints]] as they disproportionally use their larger financial resources{{snd}}which they can usually spend freely in their entirety for any purpose as long as the end user purchase is legal{{snd}}for energy-intensive goods. In particular, the largest disproportionality was identified to be in the domain of transport, where e.g. the top 10% consume 56% of vehicle fuel and conduct 70% of vehicle purchases.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Oswald |first1=Yannick |last2=Owen |first2=Anne |last3=Steinberger |first3=Julia K. |title=Large inequality in international and intranational energy footprints between income groups and across consumption categories |journal=Nature Energy |date=March 2020 |volume=5 |issue=3 |pages=231–239 |doi=10.1038/s41560-020-0579-8 |bibcode=2020NatEn...5..231O |s2cid=216245301 |language=en |issn=2058-7546|url=http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/156055/3/Submission%2520manuscript%25202.05%2520Y.O.%2520A.O.%2520J.K.S%5B1%5D.pdf }}</ref> |

|||

===Techniques=== |

|||

{{See also|Global commons|Health policy|Sustainable design}} |

|||

[[Choice editing]] refers to the active process of controlling or limiting the choices available to consumers. |

|||

[[Degrowth]] refers to economic paradigms that address the need to reduce global consumption and production whereby metrics and mechanisms like [[Gross domestic product|GDP]] are replaced by more reality-attached goals such as of measures of social and environmental well-being. |

|||

[[Personal carbon trading|Personal Carbon Allowances]] (PCAs) refers to technology-based schemes to [[rationing|ration]] GHG emissions.<ref name="10.1038/s41893-021-00756-w">{{cite journal |last1=Fuso Nerini |first1=Francesco |last2=Fawcett |first2=Tina |last3=Parag |first3=Yael |last4=Ekins |first4=Paul |title=Personal carbon allowances revisited |journal=Nature Sustainability |date=16 August 2021 |pages=1–7 |doi=10.1038/s41893-021-00756-w |language=en |issn=2398-9629|doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

== Strong and weak sustainable consumption == |

== Strong and weak sustainable consumption == |

||

| Line 31: | Line 77: | ||

The so-called [[Attitude-behavior gap|attitude-behaviour]] or [[values-action gap]] describes an obstacle to changes in individual customer behavior. Many consumers are aware of the importance of their consumption choices and care about environmental issues, however most do not translate their concerns into their consumption patterns. This is because the purchase decision process is complicated and relies on e.g. social, political, and psychological factors. Young et al. identified a lack of time for research, high prices, a lack of information, and the [[Cognition|cognitive]] effort needed as the main barriers when it comes to [[green consumption]] choices.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Young|first1=William|title=Sustainable Consumption: Green Consumer Behaviour when Purchasing Products|journal=Sustainable Development|date=2010|issue=18|pages=20–31|url=http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/77341/7/SD%20young%20et%20al%202008.pdf}}</ref> |

The so-called [[Attitude-behavior gap|attitude-behaviour]] or [[values-action gap]] describes an obstacle to changes in individual customer behavior. Many consumers are aware of the importance of their consumption choices and care about environmental issues, however most do not translate their concerns into their consumption patterns. This is because the purchase decision process is complicated and relies on e.g. social, political, and psychological factors. Young et al. identified a lack of time for research, high prices, a lack of information, and the [[Cognition|cognitive]] effort needed as the main barriers when it comes to [[green consumption]] choices.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Young|first1=William|title=Sustainable Consumption: Green Consumer Behaviour when Purchasing Products|journal=Sustainable Development|date=2010|issue=18|pages=20–31|url=http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/77341/7/SD%20young%20et%20al%202008.pdf}}</ref> |

||

== Ecological |

== Ecological awareness == |

||

The recognition that human well-being is interwoven with the natural environment, as well as an interest to change human activities that cause environmental harm.{{clarify|reason=sentence fragment|date=March 2022}}<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Ruby|first1=Matthew B.|last2=Walker|first2=Iain|last3=Watkins|first3=Hanne M.|date=2020|title=Sustainable Consumption: The Psychology of Individual Choice, Identity, and Behavior|journal=Journal of Social Issues|language=en|volume=76|issue=1|pages=8–18|doi=10.1111/josi.12376|issn=1540-4560|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

The recognition that human well-being is interwoven with the natural environment, as well as an interest to change human activities that cause environmental harm.{{clarify|reason=sentence fragment|date=March 2022}}<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Ruby|first1=Matthew B.|last2=Walker|first2=Iain|last3=Watkins|first3=Hanne M.|date=2020|title=Sustainable Consumption: The Psychology of Individual Choice, Identity, and Behavior|journal=Journal of Social Issues|language=en|volume=76|issue=1|pages=8–18|doi=10.1111/josi.12376|issn=1540-4560|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

||

== Historical |

== Historical related behaviors == |

||

In the early twentieth century, especially during the [[interwar period]], families turned to sustainable consumption.<ref name=":2" /> When unemployment began to stretch resources, American working-class families increasingly became dependent on [[Second-hand goods|secondhand goods]], such as clothing, tools, and furniture.<ref name=":2" /> Used items offered entry into consumer culture, and they also provided investment value and enhancements to wage-earning capabilities.<ref name=":2" /> [[Great Depression|The Great Depression]] saw increases in the number of families forced to turn to cast-off clothing. When wages became desperate, employers offered clothing replacements as a substitute for earnings. In response, fashion trends {{clarify|text=decelerated|date=March 2022}} as high-end clothing became a luxury. |

In the early twentieth century, especially during the [[interwar period]], families turned to sustainable consumption.<ref name=":2" /> When unemployment began to stretch resources, American working-class families increasingly became dependent on [[Second-hand goods|secondhand goods]], such as clothing, tools, and furniture.<ref name=":2" /> Used items offered entry into consumer culture, and they also provided investment value and enhancements to wage-earning capabilities.<ref name=":2" /> [[Great Depression|The Great Depression]] saw increases in the number of families forced to turn to cast-off clothing. When wages became desperate, employers offered clothing replacements as a substitute for earnings. In response, fashion trends {{clarify|text=decelerated|date=March 2022}} as high-end clothing became a luxury. |

||

During the rapid expansion of post-war suburbia, families turned to new levels of mass consumption. Following the {{clarify|text=SPI|date=March 2022}} conference of 1956, plastic corporations were quick to enter the mass consumption market of post-war America.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web|title=Reframing History: The Litter Myth : Throughline|url=https://www.npr.org/2020/08/05/899391551/reframing-history-the-litter-myth|access-date=2020-12-08|website=NPR.org|language=en}}</ref> During this period companies like [[Dixie Cup|Dixie]] began to replace reusable products with disposable containers (plastic items and metals). Unaware of how to dispose of containers, consumers began to throw waste across public spaces and national parks.<ref name=":3" /> Following a [[Vermont state legislature|Vermont State Legislature]] ban on disposable glass products, plastic corporations banded together to form the [[Keep America Beautiful]] organization in order to encourage individual actions and discourage regulation.<ref name=":3" /> The organization teamed with schools and government agencies to spread the anti-litter message. Running public service announcements like "Susan Spotless," the organization encouraged consumers to dispose waste in designated areas. |

During the rapid expansion of post-war suburbia, families turned to new levels of mass consumption. Following the {{clarify|text=SPI|date=March 2022}} conference of 1956, plastic corporations were quick to enter the mass consumption market of post-war America.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web|title=Reframing History: The Litter Myth : Throughline|url=https://www.npr.org/2020/08/05/899391551/reframing-history-the-litter-myth|access-date=2020-12-08|website=NPR.org|language=en}}</ref> During this period companies like [[Dixie Cup|Dixie]] began to replace reusable products with disposable containers (plastic items and metals). Unaware of how to dispose of containers, consumers began to throw waste across public spaces and national parks.<ref name=":3" /> Following a [[Vermont state legislature|Vermont State Legislature]] ban on disposable glass products, plastic corporations banded together to form the [[Keep America Beautiful]] organization in order to encourage individual actions and discourage regulation.<ref name=":3" /> The organization teamed with schools and government agencies to spread the anti-litter message. Running public service announcements like "Susan Spotless," the organization encouraged consumers to dispose waste in designated areas. |

||

== Recent |

== Recent culture shifts == |

||

[[File:Education on sustainable consumption should be prioritised. More specifically, concerning consumption, which two actions should be prioritised to combat climate change?.svg|thumb|Support for education on sustainable consumption as a priority for respondents to the European Investment Bank Climate Survey.]] |

[[File:Education on sustainable consumption should be prioritised. More specifically, concerning consumption, which two actions should be prioritised to combat climate change?.svg|thumb|Support for education on sustainable consumption as a priority for respondents to the European Investment Bank Climate Survey.]] |

||

Surveys ranking consumer values such as environmental, social, and sustainability, showed sustainable consumption values to be particularly low.<ref name=":4">{{Cite web|title=Consumer Market Monitor {{!}} UCD Quinn School|url=https://www.ucd.ie/quinn/facultyresearch/researchexpertise/consumermarketmonitor/ https://www.ucd.ie/quinn/media/businessschool/rankingsampaccreditations/profileimages/docs/consumermarketmonitor/CMM_Q1_2016.pdf|access-date=2020-12-08|website=www.ucd.ie}}</ref> Surveys on environmental awareness saw an increase in perceived “[[Environmentally friendly|eco-friendly]]” behavior. When tasked to reduce energy consumption, empirical research found that individuals are only willing to make minimal sacrifices and fail to reach strong sustainable consumption requirements.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Measurement and Determinants of Environmentally Significant Consumer Behavior|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249624450|access-date=2020-12-08|website=ResearchGate|language=en}}</ref> IGOs are not motivated to adopt sustainable policy decisions, since consumer demands may not meet the requirements of sustainable consumption. |

Surveys ranking consumer values such as environmental, social, and sustainability, showed sustainable consumption values to be particularly low.<ref name=":4">{{Cite web|title=Consumer Market Monitor {{!}} UCD Quinn School|url=https://www.ucd.ie/quinn/facultyresearch/researchexpertise/consumermarketmonitor/ https://www.ucd.ie/quinn/media/businessschool/rankingsampaccreditations/profileimages/docs/consumermarketmonitor/CMM_Q1_2016.pdf|access-date=2020-12-08|website=www.ucd.ie}}</ref> Surveys on environmental awareness saw an increase in perceived “[[Environmentally friendly|eco-friendly]]” behavior. When tasked to reduce energy consumption, empirical research found that individuals are only willing to make minimal sacrifices and fail to reach strong sustainable consumption requirements.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Measurement and Determinants of Environmentally Significant Consumer Behavior|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249624450|access-date=2020-12-08|website=ResearchGate|language=en}}</ref> IGOs are not motivated to adopt sustainable policy decisions, since consumer demands may not meet the requirements of sustainable consumption. |

||

Revision as of 17:03, 26 May 2022

| Part of a series on |

| Anti-consumerism |

|---|

Sustainable consumption (sometimes abbreviated to "SC")[1] is the use of material products, energy, and immaterial services in such a way that their use minimizes impacts on the environment, so that human needs can be met not only in the present but also for future generations.[2] Consumption refers not only to individuals and households, but also to governments, business, and other institutions. Sustainable consumption is closely related to sustainable production and sustainable lifestyles. "A sustainable lifestyle minimizes ecological impacts while enabling a flourishing life for individuals, households, communities, and beyond. It is the product of individual and collective decisions about aspirations and about satisfying needs and adopting practices, which are in turn conditioned, facilitated, and constrained by societal norms, political institutions, public policies, infrastructures, markets, and culture."[3]

The United Nations includes analyses of efficiency, infrastructure, and waste, as well as access to basic services, green and decent jobs, and a better quality of life for all within the concept of sustainable consumption.[4] Sustainable consumption shares a number of common features with and is closely linked to sustainable production and sustainable development. Sustainable consumption, as part of sustainable development, is part of the worldwide struggle against sustainability challenges such as climate change, resource depletion, famines, and environmental pollution.

Sustainable development as well as sustainable consumption rely on certain premises such as:

- Effective use of resources, and minimisation of waste and pollution

- Use of renewable resources within their capacity for renewal

- Fuller[clarification needed] product life-cycles

- Intergenerational and intragenerational equity

Goal 12 of the Sustainable Development Goals seeks to "ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns".[5]

The Oslo definition

In 1994 the Oslo symposium defined sustainable consumption as the consumption of goods and services that enhance quality of life while limiting the use of natural resources and noxious materials.[6]

Consumption shifting

Studies found that systemic change for "decarbonization" of humanity's economic structures[7] or root-cause system changes above politics are required[8] for a substantial impact on global warming. Such changes may result in sustainable lifestyles, along with associated products, services and expenditures,[9] being structurally supported and becoming sufficiently prevalent and effective in terms of collective greenhouse gas emission reductions.

Nevertheless, ethical consumerism usually only refers to individual choices, and not the consumption behavior and/or import and consumption policies by the decision-making of nation-states. These have however been compared for road vehicles and meat consumption per capita as well as by overconsumption.[10]

Life-cycle assessments could assess the comparative sustainability and overall environmental impacts of products – including (but not limited to): "raw materials, extraction, processing and transport; manufacturing; delivery and installation; customer use; and end of life (such as disposal or recycling)".[11]

Sustainable food consumption

The environmental impact of meat production (and dairy) are large: raising animals for human consumption accounts for approximately 40% of the total amount of agricultural output in industrialized countries. Grazing occupies 26% of the earth's ice-free terrestrial surface, and feed crop production uses about one third of all arable land.[13] A global food emissions database shows that food systems are responsible for one third of the global anthropogenic GHG emissions.[14][15] Moreover, there can be competition for resources, such as land, between growing crops for human consumption and growing crops for animals, also referred to as "food vs. feed" (see also: food security).[16][17]

Therefore, sustainable consumption also includes food consumption – shifting such to sustainable diets.

Novel foods such as under-development[18] cultured meat and dairy, existing small-scale microbial foods and ground-up insects (see also: pet food and animal feed) are shown to have the potential to reduce environmental impacts by over 80% in a study.[19][20] Many studies such as a 2022 review about meat and sustainability of food systems, animal welfare, and healthy nutrition concluded that meat consumption has to be reduced substantially for sustainable consumption. The review names broad potential measures such as "restrictions or fiscal mechanisms".[21][12]

A considerable proportion of consumers of food produced by the food system may be non-livestock animals such as pet-dogs: the global dog population is estimated to be 900 million,[22][23][needs update] of which around 20% are regarded as owned pets.[24][needs update]

Product labels

The app Code Check gives versed smartphone users some capability to scan ingredients in food, drinks and cosmetics for filtering out some of the products that are legal but nevertheless unhealthy or unsustainable from their consumption/purchases.[25] A similar "personal shopping assistant" has been investigated in a study.[26] Studies indicated a low level of use of sustainability labels on food.[27] Moreover, existing labels have been intensely criticized for invalidity or unreliability, often amounting to greenwashing or being ineffective.[11][28][29]

Product information transparency and trade control

If information is linked to products e.g. via a digital product passport, along with proper architecture and governance for data sharing and data protection, it could help achieve climate neutrality and foster dematarialisation.[31] In the EU, a Digital Product Passport is being developed. When there is an increase in greenhouse gas emissions in one country as a result of an emissions reduction by a second country with a strict climate policy this is referred to as carbon leakage.[32] In the EU, the proposed Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism could help mitigate this problem,[33] and possibly increase the capacity to account for imported pollution/harm/death-footprints. Footprints of nondomestic production are significant: for instance, a study concluded that PM2.5 air pollution induced by the contemporary free trade and consumption by the the EU as a whole (not a nation) is not included here G20 nations causes two million premature deaths annually, suggesting that the average lifetime consumption of about ~28 people in these countries causes at least one premature death (average age ~67) while developing countries "cannot be expected" to implement or be able to implement countermeasures without external support or internationally coordinated efforts.[34][30]

Transparency of supply chains is important for global goals[35] such as ending net-deforestation.[36][37][38][35] Policy-options for reducing imported deforestation also include "Lower/raise import tariffs for sustainably/unsustainably produced commodities" and "Regulate imports, e.g., through quotas, bans, or preferential access agreements".[39] However, several theories of change of policy options rely on (true / reliable) information being available/provided to "shift demand—both intermediate and final—either away from imported [forest-risk commodities (FRC)] completely, e.g., through diet shifts (IC1), or to sustainably produced FRCs, e.g., through voluntary or mandatory supply-chain transparency (IS1, RS2)."[39]

As of 2021, one approach under development is binary "labelling" of investments as "green" according to an EU governmental body-created "taxonomy" for voluntarily financial investment redirection/guidance based on this categorization.[40] The company Dayrize attempts to accurately assess environmental and social impacts of consumer products.[41]

Reliable evaluations and categorizations of products may enable measures such as policy-combinations that include transparent criteria-based eco-tariffs, bans (import control), support of selected production and subsidies which shifts, rather than mainly reduces, consumption. International sanctions during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine included restrictions on Russian fossil fuel imports while supporting alternatives, albeit these sanctions were not based on environment-related qualitative criteria of the products.

Fairness and income/spending freedoms

The bottom half of the population is directly-responsible for less than 20% of energy footprints and consume less than the top 5% in terms of trade-corrected energy. High-income individuals usually have higher energy footprints as they disproportionally use their larger financial resources – which they can usually spend freely in their entirety for any purpose as long as the end user purchase is legal – for energy-intensive goods. In particular, the largest disproportionality was identified to be in the domain of transport, where e.g. the top 10% consume 56% of vehicle fuel and conduct 70% of vehicle purchases.[42]

Techniques

Choice editing refers to the active process of controlling or limiting the choices available to consumers.

Degrowth refers to economic paradigms that address the need to reduce global consumption and production whereby metrics and mechanisms like GDP are replaced by more reality-attached goals such as of measures of social and environmental well-being.

Personal Carbon Allowances (PCAs) refers to technology-based schemes to ration GHG emissions.[43]

Strong and weak sustainable consumption

This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. The reason given is: should be rephrased as encyclopedic definition, not as action plan from the proponents' PoV. Also, who coined these terms? (October 2017) |

Some writers make a distinction between "strong" and "weak" sustainability.[44]

- Strong sustainable consumption refers to participating in viable environmental activities, such as consuming renewable and efficient goods and services (such as electric locomotive, cycling, renewable energy).[45] Strong sustainable consumption also refers to an urgency to reduce individual living space and consumption rate.

- Weak sustainable consumption is the failure to adhere to strong sustainable consumption. In other words, consumption of highly pollutant activities, such as frequent car use and consumption of non-biodegradable goods (such as plastic items, metals, and mixed fabrics).[45]

In 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), also referred to as the Earth Summit, recognized[clarification needed] sustainable consumption.[46] They also recognized the difference between strong and weak sustainable consumption but set their efforts away from strong sustainable consumption.[45]

The 1992 Earth Summit found that sustainable consumption rather than sustainable development was the center of political discourse[clarification needed].[46] Currently, strong sustainable consumption is only present in minimal precincts[clarification needed] of discussion and research. International government organizations’ (IGOs) prerogatives have kept away from strong sustainable consumption.[clarification needed] To avoid scrutiny,[clarification needed] IGOs have deemed their influences[clarification needed] as limited, often aligning its[clarification needed] interests with consumer wants and needs.[45] In doing so, they advocate for minimal eco-efficient improvements, resulting in government skepticism[clarification needed] and minimal commitments to strong sustainable consumption efforts.[47]

In order to achieve sustainable consumption, two developments have to take place: an increase in the efficiency of consumption and a change in consumption patterns and reductions in consumption levels in industrialized countries as well as rich social classes in developing countries which have also a large ecological footprint and which set an example for increasing middle classes in developing countries.[clarification needed][48] The first prerequisite is not sufficient on its own and qualifies as weak sustainable consumption. Technological improvements and eco-efficiency support a reduction in resource consumption. Once this aim has been met, the second prerequisite, the change in patterns and reduction of levels of consumption is indispensable. Strong sustainable consumption approaches also pay attention to the social dimension of well-being and assess the need for changes based on a risk-averse perspective.[clarification needed][49] In order to achieve strong sustainable consumption, changes in infrastructures as well as the choices customers have are required. In the political arena, weak sustainable consumption is more discussed.[50]

The so-called attitude-behaviour or values-action gap describes an obstacle to changes in individual customer behavior. Many consumers are aware of the importance of their consumption choices and care about environmental issues, however most do not translate their concerns into their consumption patterns. This is because the purchase decision process is complicated and relies on e.g. social, political, and psychological factors. Young et al. identified a lack of time for research, high prices, a lack of information, and the cognitive effort needed as the main barriers when it comes to green consumption choices.[51]

Ecological awareness

The recognition that human well-being is interwoven with the natural environment, as well as an interest to change human activities that cause environmental harm.[clarification needed][52]

In the early twentieth century, especially during the interwar period, families turned to sustainable consumption.[6] When unemployment began to stretch resources, American working-class families increasingly became dependent on secondhand goods, such as clothing, tools, and furniture.[6] Used items offered entry into consumer culture, and they also provided investment value and enhancements to wage-earning capabilities.[6] The Great Depression saw increases in the number of families forced to turn to cast-off clothing. When wages became desperate, employers offered clothing replacements as a substitute for earnings. In response, fashion trends decelerated[clarification needed] as high-end clothing became a luxury.

During the rapid expansion of post-war suburbia, families turned to new levels of mass consumption. Following the SPI[clarification needed] conference of 1956, plastic corporations were quick to enter the mass consumption market of post-war America.[53] During this period companies like Dixie began to replace reusable products with disposable containers (plastic items and metals). Unaware of how to dispose of containers, consumers began to throw waste across public spaces and national parks.[53] Following a Vermont State Legislature ban on disposable glass products, plastic corporations banded together to form the Keep America Beautiful organization in order to encourage individual actions and discourage regulation.[53] The organization teamed with schools and government agencies to spread the anti-litter message. Running public service announcements like "Susan Spotless," the organization encouraged consumers to dispose waste in designated areas.

Recent culture shifts

Surveys ranking consumer values such as environmental, social, and sustainability, showed sustainable consumption values to be particularly low.[54] Surveys on environmental awareness saw an increase in perceived “eco-friendly” behavior. When tasked to reduce energy consumption, empirical research found that individuals are only willing to make minimal sacrifices and fail to reach strong sustainable consumption requirements.[55] IGOs are not motivated to adopt sustainable policy decisions, since consumer demands may not meet the requirements of sustainable consumption.

Ethnographic research across Europe concluded that post-Financial crisis of 2007–2008 Ireland saw an increase in secondhand shopping and communal gardening.[56] Following a series of financial scandals, Anti-Austerity became a cultural movement. Irish consumer confidence fell, sparking a culture shift[clarification needed] in second-hand markets and charities, stressing sustainability and drawing on a narrative surrounding economic recovery[clarification needed].[54]

Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals were established by the United Nations in 2015. SDG 12 is meant to "ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns".[57] Specifically, targets 12.1 and 12.A of SDG 12 aim to implement frameworks and support developing countries in order to "move towards more sustainable patterns of consumption and production".[57]

Notable conferences and programs

- 1992—At the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) the concept of sustainable consumption was established in chapter 4 of the Agenda 21.[58]

- 1995—Sustainable consumption was requested to be incorporated by UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) into the UN Guidelines on Consumer Protection.[further explanation needed]

- 1997—A major report on SC was produced by the OECD.[59]

- 1998—United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) started a SC program and SC is discussed in the Human Development Report of the UN Development Program (UNDP).[60]

- 2002—A ten-year program on sustainable consumption and production (SCP) was created in the Plan of Implementation at the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg.[61]

- 2003—The "Marrakesh Process" was developed by co-ordination of a series of meetings and other "multi-stakeholder" processes by UNEP and UNDESA following the WSSD.[62]

- 2018—Third International Conference of the Sustainable Consumption Research and Action Initiative (SCORAI) in collaboration with the Copenhagen Business School.[63]

See also

- Choice editing

- Collaborative consumption

- Sustainable consumer behavior

- Durable goods

- Overconsumption

- Degrowth

References

- ^ Consumer Council (Hong Kong), Sustainable Consumption for a Better Future – A Study on Consumer Behaviour and Business Reporting, published 22 February 2016, accessed 13 September 2020

- ^ Our common future. World Commission on Environment and Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1987. ISBN 978-0192820808. OCLC 15489268.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Vergragt, P.J. et al (2016) Fostering and Communicating Sustainable Lifestyles: Principles and Emerging Practices, UNEP– Sustainable Lifestyles, Cities and Industry Branch, http://www.oneearthweb.org/communicating-sustainable-lifestyles-report.html , page 6.

- ^ "Sustainable consumption and production". United Nations Sustainable Development. Retrieved 2018-08-15.

- ^ "Goal 12: Responsible consumption, production". UNDP. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Source: Norwegian Ministry of the Environment (1994) Oslo Roundtable on Sustainable Production and Consumption.

- ^ Forster, Piers M.; Forster, Harriet I.; Evans, Mat J.; Gidden, Matthew J.; Jones, Chris D.; Keller, Christoph A.; Lamboll, Robin D.; Quéré, Corinne Le; Rogelj, Joeri; Rosen, Deborah; Schleussner, Carl-Friedrich; Richardson, Thomas B.; Smith, Christopher J.; Turnock, Steven T. (7 August 2020). "Current and future global climate impacts resulting from COVID-19". Nature Climate Change. 10 (10): 913–919. Bibcode:2020NatCC..10..913F. doi:10.1038/s41558-020-0883-0. ISSN 1758-6798. S2CID 221019148.

- ^ Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M.; Gregg, Jillian W.; et al. (28 July 2021). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency 2021". BioScience. 71 (9): biab079. doi:10.1093/biosci/biab079. hdl:1808/30278. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Kanyama, Annika Carlsson; Nässén, Jonas; Benders, René (2021). "Shifting expenditure on food, holidays, and furnishings could lower greenhouse gas emissions by almost 40%". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 25 (6): 1602–1616. doi:10.1111/jiec.13176. ISSN 1530-9290.

- ^ "Country Overshoot Days 2022". Earth Overshoot Day. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ a b Arratia, Ramon (18 December 2012). "Full product transparency gives consumers more informed choices". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Parlasca, Martin C.; Qaim, Matin (5 October 2022). "Meat Consumption and Sustainability". Annual Review of Resource Economics. 14. doi:10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-032340. ISSN 1941-1340.

- ^ Steinfeld, Henning; Gerber, Pierre; Wassenaar, Tom; Castel, Vincent; Rosales, Mauricio; de Haan, Cees (2006), Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options (PDF), Rome: FAO

- ^ "FAO – News Article: Food systems account for more than one third of global greenhouse gas emissions". www.fao.org. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F. N.; Leip, A. (March 2021). "Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions". Nature Food. 2 (3): 198–209. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00225-9. ISSN 2662-1355.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Manceron, Stéphane; Ben-Ari, Tamara; Dumas, Patrice (July 2014). "Feeding proteins to livestock: Global land use and food vs. feed competition". OCL. 21 (4): D408. doi:10.1051/ocl/2014020. ISSN 2272-6977.

- ^ Steinfeld, H.; Opio, C. (2010). "The availability of feeds for livestock: Competition with human consumption in present world" (PDF). Advances in Animal Biosciences. 1 (2): 421. doi:10.1017/S2040470010000488.

- ^ "Lebensmittel aus dem Labor könnten der Umwelt helfen". www.sciencemediacenter.de. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "Lab-grown meat and insects 'good for planet and health'". BBC News. 25 April 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ "Incorporation of novel foods in European diets can reduce global warming potential, water use and land use by over 80%". Nature Food. 25 April 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ "Meat consumption must fall by at least 75% for sustainable consumption, says study". University of Bonn. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Gompper, Matthew E. (2013). "The dog–human–wildlife interface: assessing the scope of the problem". In Gompper, Matthew E. (ed.). Free-Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation. Oxford University Press. pp. 9–54. ISBN 978-0191810183.

- ^ Lescureux, Nicolas; Linnell, John D.C. (2014). "Warring brothers: The complex interactions between wolves (Canis lupus) and dogs (Canis familiaris) in a conservation context". Biological Conservation. 171: 232–245. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2014.01.032.

- ^ Lord, Kathryn; Feinstein, Mark; Smith, Bradley; Coppinger, Raymond (2013). "Variation in reproductive traits of members of the genus Canis with special attention to the domestic dog (Canis familiaris)". Behavioural Processes. 92: 131–142. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2012.10.009. PMID 23124015.

- ^ Mulka, Angela (21 April 2022). "Apps for Earth Day: 5 options to keep your green goals". SFGATE. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ Asikis, Thomas; Klinglmayr, Johannes; Helbing, Dirk; Pournaras, Evangelos. "How value-sensitive design can empower sustainable consumption". Royal Society Open Science. 8 (1): 201418. doi:10.1098/rsos.201418.

- ^ Grunert, Klaus G.; Hieke, Sophie; Wills, Josephine (1 February 2014). "Sustainability labels on food products: Consumer motivation, understanding and use". Food Policy. 44: 177–189. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.12.001. ISSN 0306-9192.

- ^ "Certification schemes such as FSC are greenwashing forest destruction". Greenpeace Africa. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ Cazzolla Gatti, Roberto; Velichevskaya, Alena (10 November 2020). "Certified "sustainable" palm oil took the place of endangered Bornean and Sumatran large mammals habitat and tropical forests in the last 30 years". Science of the Total Environment. 742: 140712. Bibcode:2020ScTEn.742n0712C. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140712. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 32721759. S2CID 220852123. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ a b Nansai, Keisuke; Tohno, Susumu; Chatani, Satoru; Kanemoto, Keiichiro; Kagawa, Shigemi; Kondo, Yasushi; Takayanagi, Wataru; Lenzen, Manfred (2 November 2021). "Consumption in the G20 nations causes particulate air pollution resulting in two million premature deaths annually". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 6286. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.6286N. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26348-y. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8563796. PMID 34728619.

- ^ "https://www.epc.eu/en/events/Digitalisation-for-a-circular-economy-A-driver~30dbd0". www.epc.eu. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ Andrés Cala (18 November 2014), "Emissions Loophole Stays Open in E.U.", The New York Times, retrieved 1 April 2015

- ^ Abnett, Kate (16 March 2022). "EU countries support plan for world-first carbon border tariff". Reuters. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "Air pollution from G20 consumers caused two million deaths in 2010". New Scientist. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ^ a b Gardner, T. A.; Benzie, M.; Börner, J.; Dawkins, E.; Fick, S.; Garrett, R.; Godar, J.; Grimard, A.; Lake, S.; Larsen, R. K.; Mardas, N.; McDermott, C. L.; Meyfroidt, P.; Osbeck, M.; Persson, M.; Sembres, T.; Suavet, C.; Strassburg, B.; Trevisan, A.; West, C.; Wolvekamp, P. (1 September 2019). "Transparency and sustainability in global commodity supply chains". World Development. 121: 163–177. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.025. ISSN 0305-750X.

- ^ Nepstad, Daniel; McGrath, David; Stickler, Claudia; Alencar, Ane; Azevedo, Andrea; Swette, Briana; Bezerra, Tathiana; DiGiano, Maria; Shimada, João; Seroa da Motta, Ronaldo; Armijo, Eric; Castello, Leandro; Brando, Paulo; Hansen, Matt C.; McGrath-Horn, Max; Carvalho, Oswaldo; Hess, Laura (6 June 2014). "Slowing Amazon deforestation through public policy and interventions in beef and soy supply chains". Science. 344 (6188): 1118–1123. Bibcode:2014Sci...344.1118N. doi:10.1126/science.1248525. PMID 24904156. S2CID 206553761.

- ^ Nolte, Christoph; le Polain de Waroux, Yann; Munger, Jacob; Reis, Tiago N. P.; Lambin, Eric F. (1 March 2017). "Conditions influencing the adoption of effective anti-deforestation policies in South America's commodity frontiers". Global Environmental Change. 43: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.01.001. ISSN 0959-3780.

- ^ McAlpine, C. A.; Etter, A.; Fearnside, P. M.; Seabrook, L.; Laurance, W. F. (1 February 2009). "Increasing world consumption of beef as a driver of regional and global change: A call for policy action based on evidence from Queensland (Australia), Colombia and Brazil". Global Environmental Change. 19 (1): 21–33. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.008. ISSN 0959-3780.

- ^ a b Bager, Simon L.; Persson, U. Martin; Reis, Tiago N. P. dos (19 February 2021). "Eighty-six EU policy options for reducing imported deforestation". One Earth. 4 (2): 289–306. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2021.01.011. ISSN 2590-3330.

- ^ Abnett, Kate (9 December 2021). "EU passes first chunk of green investment rules, contentious sectors still to come". Reuters. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "The Latch Teams With SunCorp To Launch New Storefront To Help Shoppers Make Sustainable Choices". B&T. 3 May 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ Oswald, Yannick; Owen, Anne; Steinberger, Julia K. (March 2020). "Large inequality in international and intranational energy footprints between income groups and across consumption categories" (PDF). Nature Energy. 5 (3): 231–239. Bibcode:2020NatEn...5..231O. doi:10.1038/s41560-020-0579-8. ISSN 2058-7546. S2CID 216245301.

- ^ Fuso Nerini, Francesco; Fawcett, Tina; Parag, Yael; Ekins, Paul (16 August 2021). "Personal carbon allowances revisited". Nature Sustainability: 1–7. doi:10.1038/s41893-021-00756-w. ISSN 2398-9629.

- ^ Ross, A., Modern Interpretations of Sustainable Development, Journal of Law and Society, Mar., 2009, Vol. 36, No. 1, Economic Globalization and Ecological Localization: Socio-legal Perspectives (Mar., 2009), pp. 32-54

- ^ a b c d "Sustainable Consumption Governance: A History of - ProQuest". www.proquest.com. ProQuest 198357968. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ^ a b "United Nations Conference on Environment & Development" (PDF). Sustainable Development.

- ^ Perrels, Adriaan (2008-07-01). "Wavering between radical and realistic sustainable consumption policies: in search for the best feasible trajectories". Journal of Cleaner Production. The Governance and Practice of Change of Sustainable Consumption and Production. 16 (11): 1203–1217. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2007.08.008. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Meier, Lars; Lange, Hellmuth, eds. (2009). The New Middle Classes. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9938-0. ISBN 978-1-4020-9937-3.

- ^ Lorek, Sylvia; Fuchs, Doris (2013). "Strong Sustainable Consumption Governance - Precondition for a Degrowth Path?". Journal of Cleaner Production. 38: 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.08.008.

- ^ Fuchs, Doris; Lorek, Sylvia (2005). "Sustainable Consumption Governance: A History of Promises and Failures". Journal of Consumer Policy. 28 (3): 261–288. doi:10.1007/s10603-005-8490-z. S2CID 154853001.

- ^ Young, William (2010). "Sustainable Consumption: Green Consumer Behaviour when Purchasing Products" (PDF). Sustainable Development (18): 20–31.

- ^ Ruby, Matthew B.; Walker, Iain; Watkins, Hanne M. (2020). "Sustainable Consumption: The Psychology of Individual Choice, Identity, and Behavior". Journal of Social Issues. 76 (1): 8–18. doi:10.1111/josi.12376. ISSN 1540-4560.

- ^ a b c "Reframing History: The Litter Myth : Throughline". NPR.org. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ^ a b https://www.ucd.ie/quinn/media/businessschool/rankingsampaccreditations/profileimages/docs/consumermarketmonitor/CMM_Q1_2016.pdf "Consumer Market Monitor | UCD Quinn School" (PDF). www.ucd.ie. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Measurement and Determinants of Environmentally Significant Consumer Behavior". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ^ Murphy, Fiona (2017-10-15). "Austerity Ireland, the New Thrift Culture and Sustainable Consumption". Journal of Business Anthropology. 6 (2): 158–174. doi:10.22439/jba.v6i2.5410. ISSN 2245-4217.

- ^ a b UN Goal 12: Ensure Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns

- ^ United Nations. "Agenda 21" (PDF).

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (1997) Sustainable Consumption and Production, Paris: OECD.

- ^ United Nations Development Program (UNDP) (1998) Human Development Report, New York: UNDP.

- ^ United Nations (UN) (2002) Plan of Implementation of the World Summit on Sustainable Development. In Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, UN Document A/CONF.199/20*, New York: UN.

- ^ United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs (2010) Paving the Way to Sustainable Consumption and Production. In Marrakech Process Progress Report including Elements for a 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production (SCP). [online] Available at: http://www.unep.fr/scp/marrakech/pdf/Marrakech%20Process%20Progress%20Report%20-%20Paving%20the%20Road%20to%20SCP.pdf [Accessed: 6/11/2011].

- ^ "Third International Conference of the Sustainable Consumption Research and Action Initiative (SCORAI)". CBS - Copenhagen Business School. 2018-03-07. Retrieved 2020-02-21.