Entoprocta: Difference between revisions

→Names: ref for campto- |

→Names: another ref for "campto-"; ce |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

"Entoprocta", coined in 1870,<ref name="Wood2005LoxosomatoidesSirindhornae">{{cite journal|last=Wood|first=T.S.|date=2005|title=''Loxosomatoides sirindhornae'', new species, a freshwater kamptozoan from Thailand (Entoprocta)|journal=Hydrobiologia|volume=544|pages=27–31}}</ref> means "[[anus]] inside".<ref name="RuppertFoxBarnesKamptozoa">{{cite book |

"Entoprocta", coined in 1870,<ref name="Wood2005LoxosomatoidesSirindhornae">{{cite journal|last=Wood|first=T.S.|date=2005|title=''Loxosomatoides sirindhornae'', new species, a freshwater kamptozoan from Thailand (Entoprocta)|journal=Hydrobiologia|volume=544|pages=27–31}}</ref> means "[[anus]] inside".<ref name="RuppertFoxBarnesKamptozoa">{{cite book |

||

| author=Ruppert, E.E., Fox, R.S., and Barnes, R.D. | title=Invertebrate Zoology | chapter=Kamptozoa and Cycliophora | publisher=Brooks/Cole | edition=7 | isbn=0030259827 | date=2004 | page=808-812 |

| author=Ruppert, E.E., Fox, R.S., and Barnes, R.D. | title=Invertebrate Zoology | chapter=Kamptozoa and Cycliophora | publisher=Brooks/Cole | edition=7 | isbn=0030259827 | date=2004 | page=808-812 |

||

}}</ref> The alternative name "Kamptozoa", meaning "bent" or "curved" animals,<ref>The prefix "campto-" is explained at: |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*{{cite book|last=Gledhill|first=D.|title=The names of plants|publisher=Cambridge University Press|date=2008|pages=88|isbn=0521866456|url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=NJ6PyhVuecwC&dq=campto-+kampto-&source=gbs_navlinks_s|accessdate=10 Sept 2009}} |

|||

| ⚫ | *{{cite journal|last=Oestreich|first=A.E.|coauthors=Kahane, H., and Kahane, R.|title=Camptomelic dysplasia|journal=Pediatric Radiology|volume=13|issue=4|pages=246-247|doi=10.1007/BF00973171}}</ref> was assigned in 1929.<ref name="Wood2005LoxosomatoidesSirindhornae" /> Only "Entoprocta" is recognized by [[Integrated Taxonomic Information System|ITIS]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=156732|title=ITIS Standard Report Page: Entoprocta|date=2006|publisher=Integrated Taxonomic Information System|accessdate=2009-08-26}}</ref> |

||

==Description== |

==Description== |

||

Revision as of 22:20, 11 September 2009

| Entoprocts | |

|---|---|

| |

| Barentsia discreta | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Superphylum: | |

| Phylum: | Entoprocta |

| Families | |

|

Barentsiidae (Urnatellidae) | |

Entoprocta (Gr. εντος, entos inside + προκτος, proktos anus) is a phylum of small aquatic animals, ranging in size from 0.5 mm to 5.0 mm. They have a lophophore, and as their name suggests, are distinguished from other lophophorates by the position of the anus inside the ring of cilia rather than outside. Other names include goblet worm and kamptozoan.

Entoprocts are filter feeders, their tentacles secreting a mucus that catches food particles, which is then moved towards the mouth by cilia on the tentacles. Nearly all species are sedentary, attached to the substrate by a stalk, with the body being cup-shaped. Some species are colonial, with multiple animals on branching systems of stalks.

Entoprocts can reproduce either by budding, or sexually. They are unusual in being sequential hermaphrodites.

The phylum includes about 150 species in several families. While most species are marine, the freshwater species Urnatella gracilis is widespread.

Names

"Entoprocta", coined in 1870,[1] means "anus inside".[2] The alternative name "Kamptozoa", meaning "bent" or "curved" animals,[3] was assigned in 1929.[1] Only "Entoprocta" is recognized by ITIS.[4]

Description

Most species are colonial, and their members are known as "zooids",[2] since they are not fully-independent animals.[5] Zoids are typically 1 millimetre (0.039 in) long but ranging from 0.1 to 7 millimetres (0.0039 to 0.2756 in) long.[2]

Zooids

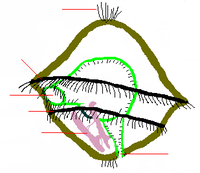

The body of a mature zooid consists of a calyx ("goblet") mounted on a relatively long stalk that attaches to a surface. The rim of the calyx bears a crown of 8 to 30 solid tentacles, which are extensions of the body wall. The base of the crown of tentacles is surrounded by a membrane that partially covers the tentacles when they retract. The mouth and anus lie on opposite sides of the atrium (space enclosed by the crown of tentacles), and both can be closed by sphincter muscles. The gut is U-shaped, curving down towards the base of the calyx, where it broadens to form the stomach. This is lined with a membrane consisting of a single layer of cells, each of which has multiple cilia.[2]

The stalks of colonial species arise from shared attachment plates or from a network of stolons, tubes that run across a surface.[2] In solitary species the stalk ends in a muscular sucker, or a flexible foot, or is cemented to a surface.[6] The stalk is muscular and produces a characteristic nodding motion. In some species it is segmented. Some solitary species can move, either by creeping on the muscular foot or by somersaulting.[2]

The body wall consists of the epidermis and an external cuticle,[2] which consists mainly of criss-cross collagen fibers. The epidermis contains only a single layer of cells, each of which bears multiple cilia ("hairs") and microvilli (tiny "pleats") that penetrate through the cuticle.[2] The stolons and stalks of colonial species have thicker cuticles, stiffened with chitin.[6]

There is no coelom (internal fluid-filled cavity lined with peritoneum) and the other internal organs are embedded in connective tissue that lies between the stomach and the base of the crown of tentacles. The nervous system runs through the connective tissue and just below the epidermis, and is controlled by a pair of ganglia. Nerves run from these to the calyx, tentacles and stalk, and to sense organs in all these areas.[2]

Feeding, digestion, excretion, circulation and respiration

A band of cells, each with multiple cilia, runs along the sides of the tentacles, connecting each tentacle to is neighbors; except that there is a gap in the band nearest the anus. A separate band of cilia runs along a groove that runs close to the inner side of the base of the crown, with a narrow extension up the inner surface of each tentacle.[6] The cilia on the sides of the tentacles create a current that flows into the crown at the bases of the tentacles and exits above the center of the crown.[2] These cilia pass food particles to the cilia on the inner surface of the tentacles, and the inner cillia produce a downward current that drives particles into and round the groove, and then to the mouth.[6] In addition glands in the tentacles secrete sticky threads that capture large particles/.[2]

The stomach and intestine are lined with microvilli, which are thought to absorb nutrients. The anus, which opens inside the crown and on a cone above the level of the groove that conducts food of the mouth, ejects solid wastes into the outgoing current after the tentacles have filtered food out of the water.[2][7] Most species have a pair of protonephridia which extract soluble wastes from the internal fluids and eliminate them through pores near the mouth. However the freshwater species Urnatella gracilis has multiple nephridia in the calyx and stalk.[2]

The zooids absorb oxygen and emit carbon dioxide by diffusion,[2] which is effective for small animals.[8]

Reproduction and life cycle

Most species are simultaneous hermaphrodites, but some switch from males to females as they mature, while individuals of some species remain of the same sex all their lives. Individuals have one or two pairs of gonads, placed between the atrium and stomach, and opening into a single gonopore in the atrium.[6] Scientists think the eggs are fertilized in the ovaries. Most species release eggs that hatch into planktonic larvae, but a few brood their eggs in the gonopore. Those that brood small eggs nourish them by a placenta-like organ, while larvae of species with larger eggs live on stored yolk.[2]

In some species the larva is a trochophore which is planktonic and feeds on floating food particles by using the two bands of cilia round its "equator" to sweep food into the mouth, which uses more cilia to drive them into the stomach, which uses further cilia to expel undigested remains through the anus.[10] In a few species the trochophore produces a pair of buds that form new individuals, while the trochophore disintegrates. However, most produce a larva with a large, cilia-bearing foot at the bottom.[6] After settling on a surface, larvae of most species undergo a complex metamorphosis, and the internal organs may rotate by up to 180°, so that the mouth and anus point upwards.[2]

All species can produce clones by budding. Colonial species produce new zooids from the stolon or from the stalks, and can form large colonies in this way.[2] In solitary species, clones form from the floor of the atrium, and are released when their organs are developed.[6]

Classification and diversity

Family Barentsiidae

- Genus Barentsia

- Genus Pedicellinopsis

- Genus Pseudopedicellina

- Genus Coriella

- Genus Urnatella

Family Loxokalypodidae

- Genus Loxokalypus

Family Loxosomatidae

- Genus Loxosoma

- Genus Loxosomella

- Genus Loxomitra

- Genus Loxosomespilon

- Genus Loxocore

Family Pedicellinidae

- Genus Pedicellina

- Genus Myosoma

- Genus Chitaspis

- Genus Loxosomatoides

Ecology

Distribution and habitats

Two live in freshwater, while the rest are marine.[1] All species are sessile. Colonial species are found in all the oceans, living on rocks, shells, algae and underwater buildings.[2] The solitary species live on other animals that feed by producing water currents, such as sponges, ectoprocts and sessile annelids. [6]

Interaction with humans

Evolutionary history

Fossil record

Family tree

References

- ^ a b c Wood, T.S. (2005). "Loxosomatoides sirindhornae, new species, a freshwater kamptozoan from Thailand (Entoprocta)". Hydrobiologia. 544: 27–31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Ruppert, E.E., Fox, R.S., and Barnes, R.D. (2004). "Kamptozoa and Cycliophora". Invertebrate Zoology (7 ed.). Brooks/Cole. p. 808-812. ISBN 0030259827.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "RuppertFoxBarnesKamptozoa" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ The prefix "campto-" is explained at:

- Gledhill, D. (2008). The names of plants. Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 0521866456. Retrieved 10 Sept 2009.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Oestreich, A.E. "Camptomelic dysplasia". Pediatric Radiology. 13 (4): 246–247. doi:10.1007/BF00973171.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Gledhill, D. (2008). The names of plants. Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 0521866456. Retrieved 10 Sept 2009.

- ^ "ITIS Standard Report Page: Entoprocta". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. 2006. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

- ^ Little, W. (1964). "Zooid". Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Nielsen, C. (2002), "Entoprocta", Encyclopedia of Life Sciences, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., doi:10.1038/npg.els.0001596

- ^ Barnes, R.S.K. (2001). "The Lophophorates". The invertebrates: a synthesis (3 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 142-143. ISBN 0632047615.

- ^ Ruppert, E.E., Fox, R.S., and Barnes, R.D. (2004). "Introduction to Metazoa". Invertebrate Zoology (7 ed.). Brooks / Cole. p. 65. ISBN 0030259827.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ruppert, E.E.; Fox, R.S. & Barnes, R.D. (2004). "Mollusca". Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 290–291. ISBN 0030259827.

- ^ Ruppert, E.E., Fox, R.S., and Barnes, R.D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology (7 ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 290–291. ISBN 0030259827.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

Nielsen, C. 1989. Entroprocts. In: D.M. Kermack & R.S.K. Barnes (eds.) Synopsis of the British Fauna No. 41.