Black-throated loon: Difference between revisions

→Taxonomy: complicated phylogeny added! |

→Behaviour: added how it is a top predator |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

==Behaviour== |

==Behaviour== |

||

This bird is considered to be a top predator in the pelagic zone of some subarctic lakes.<ref name="AmundsenLafferty2009">{{cite journal|last1=Amundsen|first1=Per-Arne|last2=Lafferty|first2=Kevin D.|last3=Knudsen|first3=Rune|last4=Primicerio|first4=Raul|last5=Klemetsen|first5=Anders|last6=Kuris|first6=Armand M.|title=Food web topology and parasites in the pelagic zone of a subarctic lake|journal=Journal of Animal Ecology|volume=78|issue=3|year=2009|pages=563–572|issn=00218790|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01518.x}}</ref> |

|||

===Breeding=== |

===Breeding=== |

||

This species can be found to habitate the area around isolated, deep freshwater lakes<ref name="Hauber2014"/> larger than {{convert|.1|km2|mi2}},<ref name="Hakeetal.2005">{{cite journal|last1=Hake|first1=Mikael|last2=Dahlgren|first2=Tomas|last3=Åhlund|first3=Matti|last4=Lindberg|first4=Peter|last5=Eriksson|first5=Mats O. G.|title=The impact of water level fluctuation on the breeding success of the black-throated diver ''Gavia arctica'' in south-west Sweden|journal=Ornis Fennica|volume=82|issue=1|pages=1–12|issn=0030-5685}}</ref> especially those with inlets.<ref name="hbw"/> It protects this territory<ref name="Petersen1979"/> and will often return to the site to nest near it.<ref name="BergmanDerksen1977"/> The oval-shaped nest is usually made on the ground,<ref name="Petersen1979">{{cite journal|last=Petersen|first=Margaret R.|title=Nesting ecology of arctic loons|journal=The Wilson Bulletin|volume=91|issue=4|year=1979|pages=608–617}}</ref> usually within {{convert|1|m|ft}} of the body of water it nests near,<ref name="Hakeetal.2005"/> out of heaped plant material like leaves and sticks on the shores of lakes.<ref name="Hauber2014">{{cite book|last=Hauber|first=Mark E.|title=The Book of Eggs: A Life-Size Guide to the Eggs of Six Hundred of the World's Bird Species|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=evQvBAAAQBAJ|date=1 August 2014|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|isbn=978-0-226-05781-1|page=53}}</ref> It also sometimes nests on vegetation, like ''[[Arctophila fulva]]'', that have emerged from lakes. Families of black-throated loons usually move their nest from the original nest ponds they inhabited to wetlands nearby after the chicks reach two weeks of age. The journey is generally less than {{convert|150|m|ft}}.<ref name="BergmanDerksen1977"/> |

This species can be found to habitate the area around isolated, deep freshwater lakes<ref name="Hauber2014"/> larger than {{convert|.1|km2|mi2}},<ref name="Hakeetal.2005">{{cite journal|last1=Hake|first1=Mikael|last2=Dahlgren|first2=Tomas|last3=Åhlund|first3=Matti|last4=Lindberg|first4=Peter|last5=Eriksson|first5=Mats O. G.|title=The impact of water level fluctuation on the breeding success of the black-throated diver ''Gavia arctica'' in south-west Sweden|journal=Ornis Fennica|volume=82|issue=1|pages=1–12|issn=0030-5685}}</ref> especially those with inlets.<ref name="hbw"/> It protects this territory<ref name="Petersen1979"/> and will often return to the site to nest near it.<ref name="BergmanDerksen1977"/> The oval-shaped nest is usually made on the ground,<ref name="Petersen1979">{{cite journal|last=Petersen|first=Margaret R.|title=Nesting ecology of arctic loons|journal=The Wilson Bulletin|volume=91|issue=4|year=1979|pages=608–617}}</ref> usually within {{convert|1|m|ft}} of the body of water it nests near,<ref name="Hakeetal.2005"/> out of heaped plant material like leaves and sticks on the shores of lakes.<ref name="Hauber2014">{{cite book|last=Hauber|first=Mark E.|title=The Book of Eggs: A Life-Size Guide to the Eggs of Six Hundred of the World's Bird Species|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=evQvBAAAQBAJ|date=1 August 2014|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|isbn=978-0-226-05781-1|page=53}}</ref> It also sometimes nests on vegetation, like ''[[Arctophila fulva]]'', that have emerged from lakes. Families of black-throated loons usually move their nest from the original nest ponds they inhabited to wetlands nearby after the chicks reach two weeks of age. The journey is generally less than {{convert|150|m|ft}}.<ref name="BergmanDerksen1977"/> |

||

Revision as of 22:14, 23 June 2017

| Black-throated loon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gaviiformes |

| Family: | Gaviidae |

| Genus: | Gavia |

| Species: | G. arctica

|

| Binomial name | |

| Gavia arctica | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Range of G. arctica Breeding range Wintering range

| |

The black-throated loon (Gavia arctica) is a migratory aquatic bird found in the northern hemisphere. The species is known as an Arctic loon in North America and the black-throated diver in Eurasia. Its current name is a compromise proposed by the International Ornithological Committee.[2]

Taxonomy

The black-throated loon was one of the many species originally described by Linnaeus in his 18th-century work, Systema Naturae.[3] The genus name Gavia comes from the Latin for "sea mew", as used by ancient Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder.[4] The specific arctica is Latin for northern or Arctic.[5]

There are two subspecies:

- Gavia arctica arctica (Linnaeus, 1758) – This subspecies is found in northern Europe, east to the center of northern Asia, and from that to the Lena River and Transbaikal. It migrates to the coasts of northwestern Europe and the coasts of the Mediterranean, Black, and Caspian Seas.[6]

- G. a. viridigularis Dwight, 1918 – This subspecies is found in eastern Russia from the Lena River and Transbaikal east to the peninsulas of Chukotka and Kamchatka and the northern portion of Sakhalin. It migrates to the northwestern Pacific coasts.[6]

The phylogeny of this species is debated, with the black-throated loon and the Pacific loon traditionally being considered sister species, whereas a study using mitochondrial DNA and nuclear intron DNA supported placing the black-throated loon sister to a clade consisting of the Pacific loon and the two sister species that are the common loon and the yellow-billed loon. In the former phylogeny, the split between the Pacific loon and the black-throated loon is proposed to have happened about 6.5 million years ago.[7]

Description

The adult black-throated loon is 58 to 77 cm (23 to 30 in) in length with a 100 to 130 cm (39 to 51 in) wingspan, shaped like a smaller, sleeker version of the great northern diver.[8] It has a weight of 1.3 to 3.4 kilograms (2.9 to 7.5 lb). The nominate subspecies in its alternate plumage has a grey head and hindneck, with a black throat and a large black patch on the foreneck, both of which have a soft purple gloss. The lower throat has a necklace-shaped patch of short parallel white lines. The sides of the throat have about five long parallel white lines that start at the side of the patch on the lower throat and run down to the chest, which also has a pattern of parallel white and black lines. The rest of the underparts, including the centre of the chest, are a pure white. The upperparts are blackish down to the base of the wing, where there are a few rows of high contrast white squares that cover the mantle and scapulars. There are small white spots on both the lesser and median coverts. The rest of the upperwing is a blackish colour. The underwing is paler than the upperwing, and the underwing coverts are white. The tail is blackish. The bill and legs are black, with a pale grey colour on the inner half of the legs. The toes and the webs are grey, with the latter also being flesh coloured. The irides are a deep brown-red. The sexes are alike, and the subspecies viridigularis is differentiated from the nominate by the former's green throat patch, compared to the latter's black throat patch.[6]

The non-breeding adult of the nominate differs from the breeding adult in that the cap and the back of the neck are more brownish. The non-breeding adult also lacks the patterned upperparts of the breeding adult, although some of the upperwing coverts do not lose their white spots. This results in the upperparts being an almost unpatterned black from above. The sides of the throat are usually darker at the white border separating the sides of the throat and the front of the throat; most of the time a thin dark necklace between these two areas can be seen. There is white on the sides of the head that are below the eye. The bill is a steel-grey with, similar to the breeding adult, a blackish tip.[6]

The juvenile is similar to the nominate non-breeding adult, but has a browner appearance. It has a buffy scaling on the upperparts that is especially pronounced on the scapulars. The lower face and front of the neck has a diffused brownish tinge. The juvenile does not have the white spots on the wing coverts, and its irides are darker and more dull in colour. The chick hatches with down feathers that range in colour from sooty-brown to brownish-grey, usually with a slightly paler head. The abdomen is pale.[6]

Vocalizations

The male, when breeding, vocalizes a loud and rhythmic "oooéé-cu-cloooéé-cu-cloooéé-cu-cluuéé" whistling song. A "áááh-oo" wail can also be heard, and a growling or croaking "knarr-knor", a sound given especially at night. The alarm call at the nest is a rising "uweek".[6]

Distribution

It breeds in Eurasia and occasionally in western Alaska. It winters at sea, as well as on large lakes over a much wider range.

Behaviour

This bird is considered to be a top predator in the pelagic zone of some subarctic lakes.[9]

Breeding

This species can be found to habitate the area around isolated, deep freshwater lakes[10] larger than .1 square kilometres (0.039 sq mi),[11] especially those with inlets.[6] It protects this territory[12] and will often return to the site to nest near it.[13] The oval-shaped nest is usually made on the ground,[12] usually within 1 metre (3.3 ft) of the body of water it nests near,[11] out of heaped plant material like leaves and sticks on the shores of lakes.[10] It also sometimes nests on vegetation, like Arctophila fulva, that have emerged from lakes. Families of black-throated loons usually move their nest from the original nest ponds they inhabited to wetlands nearby after the chicks reach two weeks of age. The journey is generally less than 150 metres (490 ft).[13]

In the southern portion of its range, this loon starts to breed in April, whereas in the northern parts of its range, it waits until the spring thaw.[6] It will usually arrive before the lake thaws, in the latter case.[14]

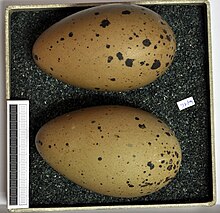

The black-throated loon lays a clutch of two, very rarely one or three,[6] 76 by 47 millimetres (3.0 by 1.9 in) eggs that are brown-green with darker speckles. These eggs are incubated by both parents for a period of 27 to 29 days,[10] with the female spending the most time out of the sexes incubating. The interval between when the egg is turned is very irregular, ranging from one minute to about six hours.[14] The hatched, mobile young are fed by both parents for a period of weeks.[10] The chicks fledge about 60 to 65 days after hatching.[6]

Nesting success, whether or not at least one chick will hatch from any given nest, is variable, with the rate of success ranging from just under 30% to just over 90%.[13] For clutches of two eggs, the average nesting success is about 50%, whereas in clutches with only one egg, the nesting success is about 60%.[15] The nesting success is influenced most by first, predation,[12] and second, flooding.[15] Some of the adults that lose their clutch early in the incubation period sometimes renest. Most of the time, only one chick survives to fledge, with the other dying before seven days after hatching.[13] This is influenced by the density of fish in the breeding lake; a lake more dense with fish will usually reduce the chances that a pair will fledge a chick, even though this loon feeds mainly on fish.[16] On average, a single pair will usually fledge a chick about 25% of the time per year.[6]

Feeding

This species feeds on fish and sometimes insects, molluscs, crustaceans, and plant matter.[6] The black-throated loon usually forages by itself or in pairs, and rarely feeding in groups with multiple species.[17] It dives from the surface into the water,[18] at depths of no more than 5 metres (16 ft). These dives are frequent, with an average of about 1.6 dives per minute. Most dives are successful, and those that are successful are usually shorter than those that are unsuccessful, with an average of 17 seconds for each successful dive, and 27 seconds for each unsuccessful dive. These dives only usually result in small food items, and those that are more profitable are usually more than 40 seconds, where this bird catches quick-swimming fish.[19]

When they are breeding, the adults will usually feed away from the nest; either at the end of the breeding lake away from the nest or at lakes near the breeding lake. When foraging for newly hatched chicks, one of the adults will forage in the lake that the nest is at or in nearby lakes, returning after a prey item had been caught. When the chicks are older, they will usually accompany both of the parents, swimming a few metres behind them. The strategy that predominates immediately after hatching is generally still employed when the chicks are older, but at a reduced rate.[20] The chicks are only fed one item of prey at a time.[14]

The diet of black-throated loon chicks varies, with what prey the breeding lake has being a large factor. For the first eight days, chicks are usually fed three-spined sticklebacks and common minnows if they are found in the breeding lake. If they are not present, then the chicks are brought up on mainly on small invertebrates until about eight days, when they are able to take trout of about 100 millimetres (3.9 in) in length. Although in these chicks trout makes up the majority of their diet, they are still fed, and in large numbers, invertebrates. In all lakes, salmonids make up an important part of the chicks diet after eight days. Salmonids, especially those between 100 and 240 millimetres (3.9 and 9.4 in), are important in the diets of older chicks. Eels are also an important food for older chicks.[20]

Miscellaneous

The black-throated diver is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies.

Instructions for constructing and deploying artificial floating islands to provide black-throated divers with nesting opportunities are given in Hancock (2000).

In 2007, RSPB Scotland and the Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) stated that it was surprised by an increase in the last 12 years in the breeding figures in the UK for the red-throated diver and the rarer black-throated diver of 16% and 34% respectively due to the anchoring of 58 man-made rafts in lochs. Both species decreased elsewhere in Europe.

The black-throated diver is the current school emblem of Achfary Primary School.

Dr Mark Eaton, an RSPB scientist, traced the drop in overall numbers to warming of the North Sea which reduced stocks of the fish on which they feed.[21]

References

Citations

- ^ Template:IUCN

- ^ Gill, F.; Wright, M.; Donsker, D., eds. (2009). "IOC World Bird List (v 2.2)". Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- ^ Template:La icon Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. Holmiae [Stockholm]: Laurentii Salvii.

- ^ Johnsgard, Paul A. (1987). Diving Birds of North America. University of Nevada–Lincoln. ISBN 0-8032-2566-0.

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Carboneras, C.; Garcia, E. F. J. (2017). del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi; Christie, David A.; de Juana, Eduardo (eds.). "Arctic Loon (Gavia arctica)". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Sprengelmeyer, Quentin D. (2014). A phylogenetic reevaluation of the genus Gavia (Aves: Gaviiformes) using next-generation sequencing (Master of Science). Northern Michigan University.

- ^ "Arctic Loon". enature.com. eNature. 2011. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Amundsen, Per-Arne; Lafferty, Kevin D.; Knudsen, Rune; Primicerio, Raul; Klemetsen, Anders; Kuris, Armand M. (2009). "Food web topology and parasites in the pelagic zone of a subarctic lake". Journal of Animal Ecology. 78 (3): 563–572. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01518.x. ISSN 0021-8790.

- ^ a b c d Hauber, Mark E. (1 August 2014). The Book of Eggs: A Life-Size Guide to the Eggs of Six Hundred of the World's Bird Species. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-226-05781-1.

- ^ a b Hake, Mikael; Dahlgren, Tomas; Åhlund, Matti; Lindberg, Peter; Eriksson, Mats O. G. "The impact of water level fluctuation on the breeding success of the black-throated diver Gavia arctica in south-west Sweden". Ornis Fennica. 82 (1): 1–12. ISSN 0030-5685.

- ^ a b c Petersen, Margaret R. (1979). "Nesting ecology of arctic loons". The Wilson Bulletin. 91 (4): 608–617.

- ^ a b c d Bergman, Robert D.; Derksen, Dirk V. (1977). "Observations on arctic and red-throated loons at Storkersen Point, Alaska". Arctic. 30 (1): 41–51.

- ^ a b c Sjolander, Sverre (1978). "Reproductive behaviour of the black-throated diver Gavia arctica". Ornis Scandinavica. 9 (1): 51–65. doi:10.2307/3676139. ISSN 0030-5693.

- ^ a b Mudge, G. P.; Talbot, T. R. (2008). "The breeding biology and causes of nest failure of Scottish black-throated divers Gavia arctica". Ibis. 135 (2): 113–120. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1993.tb02822.x. ISSN 0019-1019.

- ^ Eriksson, Mats O. G. (1986). "Reproduction of black-throated diver Gavia arctica in relation to fish density in oligotrophic lakes in southwestern Sweden". Ornis Scandinavica. 17 (3): 245–248. doi:10.2307/3676833. ISSN 0030-5693.

- ^ Baltz, D. M.; Morejohn, G. Victor (1977). "Food habits and niche overlap of seabirds wintering on Monterey Bay, California". The Auk. 94 (3): 526–543.

- ^ De Graaf, Richard M.; Tilghman, Nancy G.; Anderson, Stanley H. (1985). "Foraging guilds of North American birds". Environmental Management. 9 (6): 493–536. doi:10.1007/BF01867324. ISSN 0364-152X.

- ^ Bundy, Graham (2009). "Breeding and feeding observations on the black-throated diver". Bird Study. 26 (1): 33–36. doi:10.1080/00063657909476614. ISSN 0006-3657.

- ^ a b Jackson, Digger B. (2002). "Between-lake differences in the diet and provisioning behaviour of black-throated divers Gavia arctica breeding in Scotland". Ibis. 145 (1): 30–44. doi:10.1046/j.1474-919X.2003.00119.x. ISSN 0019-1019.

- ^ "Rise in divers mystifies experts". BBC NEWS. 7 September 2007.

Bibliography

- Hancock, Mark (2000). "Artificial floating islands for nesting Black-throated Divers Gavia arctica in Scotland: construction, use and effect on breeding success". Bird Study. 47 (2): 165–175. doi:10.1080/00063650009461172.

- Peter (1988). Seabirds (2nd ed.). London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7470-1410-8.

- Field Guide to the Birds of North America. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. 2002. ISBN 0-7922-6877-6.

Identification

- Appleby, R.H.; Madge, S.C.; Mullarney, Killian (1986). "Identification of divers in immature and winter plumages". British Birds. 79 (8): 365–391.

- Birch, A.; Lee, C.T. (1997). "Field identification of Arctic and Pacific Loons". Birding. 29: 106–115.

- Birch, A.; Lee, C.T. (1995). "Identification of the Pacific Diver - a potential vagrant to Europe". Birding World. 8: 458–466.

External links

- Flicker Field Guide Birds of the World Photographs

- Black-throated Diver Gavia arctica at BTO BirdFacts

- Profile Arctic Loon at avibirds.com

- Arctic Loon - A Field Guide to Birds of Armenia

- BirdLife species factsheet for Gavia arctica

- "Gavia arctica". Avibase.

- "Black-throated Diver media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Arctic Loon photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Audio recordings of Black-throated loon on Xeno-canto.