Planet Nine: Difference between revisions

m 'Centaurs' (with initial cap) in body text changed/made consistent as 'centaurs' (all lower case) throughout, as per usage in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centaur_(minor_planet) |

→Subsequent efforts toward indirect detection: orbits of comets |

||

| Line 270: | Line 270: | ||

In a paper by Carlos and Raul de la Fuente Marcos evidence is shown for a possible bimodal distribution of the nodal distances of the ETNOs. This correlation is unlikely to be the result of observational bias since it also appears in the nodal distribution of large semi-major axis centaurs and comets. If it is due to the extreme TNOs experiencing close approaches to Planet Nine, it is consistent with a planet with a semi-major axis of 300–400 AU.<ref name=nodes>{{cite journal |last1=de la Fuente Marcos |first1=Carlos |last2=de la Fuente Marcos |first2=Raúl |date=2017 |title=Evidence for a possible bimodal distribution of the nodal distances of the extreme trans-Neptunian objects: avoiding a trans-Plutonian planet or just plain bias? |journal=[[Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters]] |volume= |issue= |pages= |arxiv=1706.06981 |bibcode=2017arXiv170606981D |doi=10.1093/mnrasl/slx106 }}</ref> |

In a paper by Carlos and Raul de la Fuente Marcos evidence is shown for a possible bimodal distribution of the nodal distances of the ETNOs. This correlation is unlikely to be the result of observational bias since it also appears in the nodal distribution of large semi-major axis centaurs and comets. If it is due to the extreme TNOs experiencing close approaches to Planet Nine, it is consistent with a planet with a semi-major axis of 300–400 AU.<ref name=nodes>{{cite journal |last1=de la Fuente Marcos |first1=Carlos |last2=de la Fuente Marcos |first2=Raúl |date=2017 |title=Evidence for a possible bimodal distribution of the nodal distances of the extreme trans-Neptunian objects: avoiding a trans-Plutonian planet or just plain bias? |journal=[[Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters]] |volume= |issue= |pages= |arxiv=1706.06981 |bibcode=2017arXiv170606981D |doi=10.1093/mnrasl/slx106 }}</ref> |

||

===Orbits of nearly parabolic comets=== |

|||

An analysis of the orbits of comets with nearly parabolic orbits identifies five new comets with hyperbolic orbits that approach the nominal orbit of Planet Nine described in Batygin's and Brown's initial paper. If these orbits are hyperbolic due to close encounters with Planet Nine their analysis estimates that Planet Nine is currently near aphelion with a right ascension of 83° - 90° and a declination of 8° - 10°.<ref name="Medvedev_etal_2017">{{cite journal|last1=Medvedev|first1=Yu. D.|last2=Vavilov|first2=D. E.|last3=Bondarenko|first3=Yu. S.|last4=Bulekbaev|first4=D. A.|last5=Kunturova|first5=N. B.|title=Improvement of the position of planet X based on the motion of nearly parabolic comets|journal=Astronomy Letters|date=2017|volume=42|issue=2|pages=120-125|doi=10.1134/S1063773717020037|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1134%2FS1063773717020037}}</ref> Scott Sheppard, who is skeptical of this analysis, notes that a lot of forces influence the orbits of comets.<ref name=sciamGiantGhost/> |

|||

===Search for additional extreme trans-Neptunian objects=== |

===Search for additional extreme trans-Neptunian objects=== |

||

Revision as of 19:47, 24 July 2017

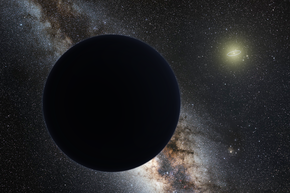

Artist's impression of Planet Nine as an ice giant eclipsing the central Milky Way, with the Sun in the distance.[2] Neptune's orbit is shown as a small ellipse around the Sun. (See labeled version.) | |

| Orbital characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Aphelion | 1,200 AU (est.)[2] |

| Perihelion | 200 AU (est.)[3] |

| 700 AU (est.)[1] | |

| Eccentricity | 0.6 (est.)[3] |

| 10,000 to 20,000 years[3] | |

| Inclination | 30° to ecliptic (est.)[1] |

| 150° (est.)[1] | |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean radius | 13,000 to 26,000 km (8,000–16,000 mi) 2–4 R🜨 (est.)[3] |

| Mass | 6×1025 kg (est.)[3] ≥10 ME (est.) |

| >22.5 (est.)[2] | |

Planet Nine is a hypothetical large planet in the far outer Solar System, the gravitational effects of which would explain the improbable orbital configuration of a group of trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) that orbit mostly beyond the Kuiper belt.[1][4][5]

In a 2014 letter to the journal Nature, astronomers Chad Trujillo and Scott S. Sheppard inferred the possible existence of a massive trans-Neptunian planet from similarities in the orbits of the distant trans-Neptunian objects Sedna and 2012 VP113.[4] On 20 January 2016, researchers Konstantin Batygin and Michael E. Brown at Caltech explained how a massive outer planet would be the likeliest explanation for the similarities in orbits of six distant objects, and they proposed specific orbital parameters.[1] The predicted planet could be a super-Earth, with an estimated mass of 10 Earths (approximately 5,000 times the mass of Pluto), a diameter two to four times that of Earth, and a highly elliptical orbit with an orbital period of approximately 15,000 years.[6]

On the basis of models of planet formation that might include planetary migration from the inner Solar System, such as the five-planet Nice model, Batygin and Brown suggest that it may be a primordial giant planet core that was ejected from its original orbit during the nebular epoch of the Solar System's evolution.[1] Others have proposed that it was captured from another star,[7] or that it formed on a very distant circular orbit and was perturbed onto its current eccentric orbit during a distant encounter with another star.[8][9]

Naming

Planet Nine does not have an official name, and it will not receive one unless its existence is confirmed, typically through optical imaging. Once confirmed, the IAU will certify a name, with priority typically given to a name proposed by its discoverers.[10] It will likely be a name chosen from Roman or Greek mythology.[11]

In their original paper, Batygin and Brown simply referred to the object as "perturber",[1] and only in later press releases did they use "Planet Nine".[12] They have also used the names "Jehoshaphat" and "George" for Planet Nine. Brown has stated: "We actually call it Phattie[A] when we're just talking to each other."[5]

Postulated characteristics

Orbit

Planet Nine is hypothesized to follow a highly elliptical orbit around the Sun, with an orbital period of 10,000–20,000 years. The period with which it goes around the sun is a rational multiple of the periods of all the furthest Kuiper Belt objects.[14] The planet's orbit would have a semi-major axis of approximately 700 AU, or about 20 times the distance from Neptune to the Sun, although it might come as close as 200 AU (30 billion km, 19 billion mi), and its inclination estimated to be roughly 30°±10°.[2][3][15][B] The high eccentricity of Planet Nine's orbit could take it as far away as 1,200 AU at its aphelion.[16][17]

The aphelion, or farthest point from the Sun, would be in the general direction of the constellation of Taurus,[18] whereas the perihelion, the nearest point to the Sun, would be in the general direction of the southerly areas of Serpens (Caput), Ophiuchus, and Libra.[19][20]

Brown thinks that if Planet Nine is confirmed to exist, a probe could fly by it in as little as 20 years, with a powered slingshot around the Sun.[21]

Size

The planet is estimated to have 10 times the mass[13][15] and two to four times the diameter of Earth.[6][23] An object with the same diameter as Neptune has not been excluded by previous surveys. An infrared survey by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) in 2009 allowed for a Neptune-sized object beyond 700 AU.[24] A similar study in 2014 focused on possible higher-mass bodies in the outer Solar System and ruled out Jupiter-mass objects out to 26,000 AU.[25]

Brown thinks that no matter where it is speculated to be, if Planet Nine exists, then its mass is higher than what is required to clear its feeding zone in 4.6 billion years, and thus that it dominates the outer edge of the Solar System, which is sufficient to make it a planet by current definitions.[26] Using a metric based on work by Jean-Luc Margot, Brown calculated that only at the smallest size and farthest distance was it on the border of being called a dwarf planet.[26] Margot himself says that Planet Nine satisfies the quantitative criterion for orbit-clearing developed by him in 2015, and that according to that criterion, Planet Nine will qualify as a planet—if and when it is detected.[27]

Composition

Brown speculates that the predicted planet is most likely an ejected ice giant, similar in composition to Uranus and Neptune: a mixture of rock and ice with a small envelope of gas.[2][6]

Hypotheses

Attempts to detect planets beyond Neptune by indirect means such as orbital perturbation date back beyond the discovery of Pluto. A few observations were directly related to the Planet Nine hypothesis:

- The discovery of Sedna with its peculiar orbit in 2004 led to the conclusion that something beyond the known eight planets had perturbed Sedna away from the Kuiper belt. That object could have been an unknown planet on a distant orbit, a random star that passed near the Solar System, or a member of the Sun's birth cluster.[28][29][30]

- In 2008 Tadashi Mukai and Patryk Sofia Lykawka suggested that a distant Mars- or Earth-sized minor planet currently in a highly eccentric orbit between 100 and 200 AU and orbital period of 1000 years with an inclination of 20° to 40° was responsible for the structure of the Kuiper belt. They proposed that the perturbations of this planet excited the eccentricities and inclinations of the trans-Neptunian objects, truncated the planetesimal disk at 48 AU, and detached the orbits of some objects from Neptune. During Neptune's migration this planet is posited to have been captured in an outer resonance of Neptune and to have evolved onto a higher perihelion orbit due to the Kozai mechanism leaving the remaining trans-Neptunian objects on stable orbits.[31][32][33][34]

- In 2012, after analysing the orbits of a group of trans-Neptunian objects with highly elongated orbits, Rodney Gomes of the National Observatory of Brazil proposed that their orbits were due to the existence of an as yet undetected planet. This Neptune-massed planet would be on a distant orbit that would be too far away to influence the motions of the inner planets, yet close enough to cause the perihelia of scattered disc objects with semi-major axes greater than 300 AU to oscillate, delivering them onto planet-crossing orbits similar to those of (308933) 2006 SQ372 and (87269) 2000 OO67 or detached orbits like that of Sedna. Alternatively the unusual orbits of these objects could be the result of a Mars-massed planet on an eccentric orbit that occasionally approached within 33 AU.[35][36] Gomes argued that a new planet was the more probable of the possible explanations but others felt that he could not show real evidence that suggested a new planet.[37] Later in 2015, Rodney Gomes, Jean Soares, and Ramon Brasser proposed that a distant planet was responsible for an excess of centaurs with large semi-major axes.[38][39]

- The announcement in March 2014 of the discovery of a second sednoid, 2012 VP113, which shared some orbital characteristics with Sedna and other extreme trans-Neptunian objects, further raised the possibility of an unseen super-Earth in a large orbit.[40][41]

Trujillo and Sheppard (2014)

The initial argument that the clustering of orbital elements of extreme trans-Neptunian objects such as sednoids might be caused by a massive unknown planet beyond Neptune was published in 2014 by astronomers Chad Trujillo and Scott S. Sheppard. Trujillo and Sheppard analyzed the orbits of twelve trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) with perihelia greater than 30 AU and semi-major axes greater than 150 AU, and found they had a clustering of orbital characteristics, particularly their arguments of perihelion (which indicates the orientation of elliptical orbits within their orbital planes).[1][4] In numerical simulations including only the known giant planets the arguments of perihelion of these objects circulated at varying rates which after billions of years would leave the perihelia of the twelve TNOs randomized, like in the rest of the trans-Neptunian region, unless there is something holding them in place.[42][C] Trujillo and Sheppard suggested that the massive unknown planet at a few hundred astronomical units caused the arguments of perihelion of the extreme trans-Neptunian objects to librate about 0° or 180°[D] via the Kozai mechanism so that their orbits cross the plane of the planet's orbit near perihelion and aphelion, at the closest and farthest points from the planet.[45][4] Numerical simulations with a single body of 2–15 Earth masses in a circular low-inclination orbit between 200 AU and 300 AU indicated that the arguments of perihelia of Sedna and 2012 VP113 would librate around 0° for billions of years (although the lower perihelion objects did not) and would undergo periods of libration with a Neptune mass object in a high inclination orbit at 1500 AU.[4]

These simulations showed the basic idea of how a single large planet can shepherd the smaller extreme trans-Neptunian objects into similar types of orbits. It was a basic proof of concept simulation that did not obtain a unique orbit for the planet as they state there are many possible orbital configurations the planet could have.[42] Thus they did not fully formulate a model that successfully incorporated all the clustering of the extreme objects with an orbit for the planet.[1] But they were the first to notice there was a clustering in the orbits of extremely distant objects and that the most likely reason was from an unknown massive distant planet. Their work is very similar to how Alexis Bouvard noticed Uranus' motion was peculiar and suggested that it was likely gravitational forces from an unknown 8th planet, which led to the discovery of Neptune.

In a later work announcing the discovery of several more distant objects Trujillo and Sheppard noted a correlation between the longitude of perihelion and the argument of perihelion of these objects. Those with a longitude of perihelion of 0–120° have arguments of perihelion between 280–360°, and those with longitude of perihelion of 180–340° have argument of perihelion 0–40°. They found a statistical significance of this correlation of 99.99%.[46]

de la Fuente Marcos et al. (2014)

In June 2014, Raúl and Carlos de la Fuente Marcos included a thirteenth minor planet and noted that all have their argument of perihelion close to 0°.[45][47] In a further analysis, Carlos and Raúl de la Fuente Marcos with Sverre J. Aarseth confirmed that the only known way that the observed alignment of the arguments of perihelion can be explained is by an undetected planet. They also theorized that a set of extreme trans-Neptunian objects (ETNOs) are kept bunched together by a Kozai mechanism similar to the one between Comet 96P/Machholz and Jupiter.[48] They speculated that it would have a mass between that of Mars and Saturn and would orbit at some 200 AU from the Sun. However, they also struggled to explain the orbital alignment using a model with only one unknown planet.[E] They therefore suggested that this planet is itself in resonance with a more-massive world about 250 AU from the Sun, just like the one predicted in the work by Trujillo and Sheppard.[42][49] They also did not rule out the possibility that the planet could have to be much farther away but much more massive in order to have the same effect and admitted the hypothesis needed more work.[50] They also did not rule out other explanations and expected more clarity as researchers study orbits of more such distant objects.[51][52][53]

Batygin and Brown (2016)

Clustering

Caltech's Konstantin Batygin and Michael E. Brown looked into refuting the mechanism proposed by Trujillo and Sheppard.[1] After eliminating the objects in Trujillo and Sheppard's original analysis that were unstable due to close approaches to Neptune or were affected by Neptune mean-motion resonances they determined that the arguments of perihelion for the remaining six objects (namely Sedna, 2012 VP113, 2004 VN112, 2010 GB174, 2010 VZ98, 2000 CR105) were 318°±8°. This was out of alignment with how the Kozai mechanism would align these orbits, at c. 0° or 180°.[1][F]

Batygin and Brown also found that the orbits of the six objects with semimajor axes greater than 250 AU and perihelia beyond 30 AU (namely Sedna, 2012 VP113, 2007 TG422, 2004 VN112, 2013 RF98, 2010 GB174) were aligned in space with their perihelia in roughly the same direction and approximately co-planar. They determined that there was only a 0.007% likelihood that this was due to chance.[1][12][55][56]

These six objects had been discovered by six different surveys on six different telescopes. That made it less likely that the clumping might be due to an observation bias such as pointing a telescope at a particular part of the sky. These six were the only minor planets known to have perihelia greater than 30 AU and a semi-major axis greater than 250 AU, as of January 2016.[57]Most have perihelia significantly beyond Neptune, which orbits 30 AU from the Sun.[13][58] Generally, TNOs with perihelia smaller than 36 AU experience strong encounters with Neptune.[1] All six objects are relatively small, but currently relatively bright because they are near their closest distance to the Sun in their elliptical orbits.

In a companion paper the cluster was extended to include a seventh object 2000 CR105 with a semi-major axis of 227 AU and the absence of objects with perihelia beyond 42 AU and semi-major axes between 100 AU and 200 AU was noted.[59]

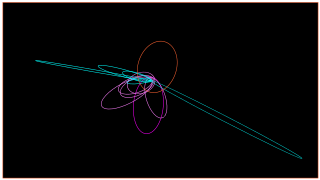

Including the original 6 and 4 new objects: 2013 FT28, 2014 FE72, 2014 SR349, and 2013 SY99, the first being aligned with P9 and the second being of extremely high eccentricity. Neptune's orbit is the small central circle around the sun. |

6 original and 7 new TNO orbits with current positions near their perihelion in purple, with hypothetical Planet nine orbit in green |

Closer up view of the 13 TNO current positions |

| Object | Orbit | orbital plane | Body | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barycentric[G] Orbital period (years) |

Barycentric Semimaj. (AU) |

Peri. (AU) |

Barycentric Aphel. (AU) |

Curr. dist. from Sun (AU) |

Ecc. | Arg. peri ω (°) |

incl. i (°) |

Long. asc ☊ or Ω (°) |

Long. peri ϖ =ω+Ω (°) |

Hv | Current mag. |

Diam. (km) | |

| 2012 VP113 | 4,300 | 266 | 80.27 | 441 | 83.5 | 0.69 | 292.8 | 24.1 | 90.8 | 23.6 | 4.0 | 23.3 | 600 |

| 2013 RF98 | 6,900 | 364 | 36.10 | 690 | 36.8 | 0.90 | 311.8 | 29.6 | 67.6 | 19.4 | 8.7 | 24.4 | 70 |

| 2004 VN112 | 5,900 | 327 | 47.32 | 607 | 47.7 | 0.85 | 327.1 | 25.6 | 66.0 | 33.1 | 6.5 | 23.3 | 200 |

| 2007 TG422 | 11,300 | 503 | 35.57 | 970 | 37.3 | 0.93 | 285.7 | 18.6 | 112.9 | 38.6 | 6.2 | 22.0 | 200 |

| 90377 Sedna | 11,400 | 507 | 76.04 | 936 | 85.5 | 0.85 | 311.5 | 11.9 | 144.5 | 96.0 | 1.5 | 20.9 | 1,000 |

| 2010 GB174 | 6,600 | 351 | 48.76 | 654 | 71.2 | 0.87 | 347.8 | 21.5 | 130.6 | 118.4 | 6.5 | 25.1 | 200 |

| 2013 FT28 | 5,050 | 295 | 43.60 | 546 | 57.0 | 0.86 | 40.2 | 17.3 | 217.8 | 258.0 (*) | 6.7 | 24.4 | 200 |

| 2014 FE72 | 58,000 | 1,500 | 36.31 | 2,960 | 61.5 | 0.98 | 134.4 | 20.6 | 336.8 | 111.2 | 6.1 | 24.0 | 200 |

| 2014 SR349 | 5,160 | 299 | 47.57 | 549 | 56.3 | 0.84 | 341.4 | 18.0 | 34.8 | 16.2 | 6.6 | 24.2 | 200 |

| 2013 SY99 | 19,700 | 730 | 49.91 | 1,410 | 60.3 | 0.93 | 32.4 | 4.2 | 29.5 | 61.9 | 6.7 | 24.5 | 250 |

| 2015 GT50 | 5510 | 310 | 38.45 | 580 | 41.7 | 0.89 | 129.2 | 8.8 | 46.1 | 175.3 (*) | 8.5 | 24.9 | 80 |

| 2015 RX245 | 8,920 | 430 | 45.48 | 815 | 61.4 | 0.89 | 65.4 | 12.2 | 8.6 | 74.0 | 6.2 | 24.2 | 250 |

| 2015 KG163 | 17,730 | 680 | 40.51 | 1,320 | 40.8 | 0.95 | 32.0 | 14.0 | 219.1 | 251.1 (*) | 8.1 | 24.3 | 100 |

| Ideal range for ETNOs under the hypothesis |

>250 | >30 | >0.5 | 10~30 | 2~120 | ||||||||

| Hypothesized Planet Nine |

~15,000 | ~700 | ~200 | ~1,200 | ~1,000? | ~0.6 | ~150 | ~30 | 91±15 | 241±15 | >22 | ~40,000 | |

(*) longitude of perihelion, ϖ, outside expected range

Simulation

Batygin and Brown simulated the effect of a planet of mass M = 10 ME[H] with a semi-major axis ranging from 200 to 2,000 AU and an eccentricity varying from 0.1 to 0.9 on these extreme TNOs and inner Oort cloud objects. The capture of Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) into long-lived apsidally anti-aligned orbital configurations occurs, with variable success, across a significant range of companion parameters (semi-major axis a ≈ 400–1,500 AU, eccentricity e ≈ 0.5–0.8).

They found that orbital parameters centered around the following values produced the best fit for the observed distribution of orbits.

- aphelion ≈ 1,200 AU, perihelion ≈ 200 AU, semi-major axis a ≈ 700 AU,

- eccentricity e ≈ 0.6, orbital period 10,000 to 20,000 years,

- an inclination i ≈ 30° to the ecliptic,[I]

- an argument of perihelion ω ≈ 150° and longitude of perihelion ϖ = 241°±15° (both the longitude and argument of perihelion are about 180° away from the 6 clustered extreme TNOs).[1]

Upon running the simulations, Batygin and Brown found that their hypothetical planet produced a number of effects on the orbits of distant minor planets, some of which were later confirmed by observation. The simulations showed that planetesimal swarms could be sculpted into collinear groups of spatially confined orbits by Planet Nine if it is substantially more massive than Earth and on a highly eccentric orbit. The confined orbits would cluster in a configuration where the long axes of their orbits are anti-aligned with respect to Planet Nine, signalling that the dynamical mechanism at play is resonant in nature.[12] This mechanism, known as phase protection, prevents the trans-Neptunian objects trapped in mean-motion resonance from having close encounters with Planet Nine, and keeps them aligned.[15] Further simulations (published later in a companion paper) showed:[59]

- appearance of strong anti-alignment for objects with semi-major axis beyond 250 AU.

- preference for slight alignment for objects with semi-major axis ranging between 100–250 AU.

- poles of the orbits of anti-aligned objects roughly aligned with Planet Nine's.

- no reproduction of the apparent alignment of arguments of perihelion.

- the tight clustering observed at that time was atypical even with Planet Nine. [J]

The resonances at play are exotic and interconnected, yielding orbital evolution that is fundamentally chaotic. In other words, perturbed by Planet Nine, the distant orbits of the Kuiper belt remain approximately aligned, while changing their shape unpredictably on million-year timescales.[63]

The results of their simulations also predicted there should be a population of objects with a perpendicular orbital inclination (relative to the first set of TNOs considered and the Solar System in general) and they realized that objects such as 2008 KV42 and 2012 DR30 fit this prediction of the model.[1][64][65] These objects would have a high semi-major axis and an inclination greater than 60°.[1] These objects may be created by the Kozai effect inside the mean-motion resonances.[12] The only TNOs known with a semi-major axis greater than 250 AU, an inclination greater than 40°, and perihelion beyond Jupiter are: (336756) 2010 NV1, (418993) 2009 MS9, 2010 BK118, 2012 DR30, and 2013 BL76.[66] When the elongated perpendicular centaurs get too close to a giant planet, orbits such as 2008 KV42 are created.[67][68]

Simulations have shown that objects with a semi-major axis less than 150 AU are largely unaffected by the presence of Planet Nine, because they have a very low chance of coming in its vicinity.[1] The simulation also predicts a yet-to-be-discovered population of high perihelion objects that have semi-major axes greater than 250 AU, and orbits that would be aligned with Planet Nine. Although they may include high eccentricity objects the most stable of these objects would have lower eccentricities.[1][K] The simulations showed that Planet Nine temporarily raises the perihelia of large semi-major axis trans-Neptunian objects, in half a billion years Sedna will be a more typical trans-Neptunian object and scattered disk objects that have large semi-major axis orbits could be in Sedna-like orbits.[71]

| Object | Orbit | Body | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perihelion (AU) Figure 9[1] |

Semimaj. (AU) Figure 9[1] |

Current distance from Sun (AU) |

inc (°)[66] |

Eccen. | Arg. peri ω (°) |

Mag. | Diam. (km) | |

| (336756) 2010 NV1 | 9.4 | 323 | 14 | 141 | 0.97 | 133 | 22 | 20–45 |

| (418993) 2009 MS9 | 11.1 | 348 | 12 | 68 | 0.97 | 129 | 21 | 30–60 |

| 2010 BK118 | 6.3 | 484 | 11 | 144 | 0.99 | 179 | 21 | 20–50 |

| 2013 BL76 | 8.5 | 1,213 | 11 | 99 | 0.99 | 166 | 21.6 | 15–40 |

| 2012 DR30 | 14 | 1,404 | 17 | 78 | 0.99 | 195 | 19.6 | 185[72] |

Inference

Batygin was cautious in interpreting the results, saying, "Until Planet Nine is caught on camera it does not count as being real. All we have now is an echo."[73] Batygin's and Brown's work is similar to how Urbain Le Verrier predicted the position of Neptune based on Alexis Bouvard's observations and theory of Uranus' peculiar motion.

Brown put the odds for the existence of Planet Nine at about 90%.[6] Greg Laughlin, one of the few researchers who knew in advance about this paper, gives an estimate of 68.3%.[5] Other skeptical scientists demand more data in terms of additional KBOs to be analysed or final evidence through photographic confirmation.[58][74][75] Brown, though conceding the skeptics' point, still thinks that there is enough data to mount a search for a new planet.[76]

Brown is supported by Jim Green, director of NASA's Planetary Science Division, who said that "the evidence is stronger now than it's ever been before".[77]

Tom Levenson concluded that, for now, Planet Nine seems the only satisfactory explanation for everything now known about the outer regions of the Solar System.[73] Alessandro Morbidelli, who reviewed the paper for The Astronomical Journal, concurred, saying, "I don't see any alternative explanation to that offered by Batygin and Brown."[5][6]

Alternate hypotheses

Inclination instability due to mass of undetected objects

Ann-Marie Madigan and Michael McCourt postulate that a yet to be discovered belt of objects far more massive than the current-day Kuiper belt, at larger distances, and preferentially tilted from the plane of the planets could be shaping the orbits of these ETNOs based on self-organization. But Brown remains confident that his and Batygin's hypothesis is correct, and regards the prospect of Planet Nine as more probable, because surveys do not suggest/support the existence of a scattered-disk region of sufficient mass to support this idea of "inclination instability".[78][79][L]

Object in lower-eccentricity orbit

Renu Malhotra, Kathryn Volk, and Xianyu Wang have proposed that the four detached objects with the longest orbital periods, those with perihelia beyond 40 AU and semi-major axes greater than 250 AU, are in n:1 or n:2 mean-motion resonances with a hypothetical planet. There are two more objects with semi-major axes greater than 150 AU. Their proposed planet could be on a lower eccentricity orbit, with e < 0.18. Unlike Batygin and Brown, they do not specify that most of the distant detached objects would have orbits anti-aligned with the massive planet.[80]

| Body | Orbital period Heliocentric (years) |

Orbital period Barycentric (years) |

Semimaj. (AU) |

Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 GP136 | 1,830 | 151.8 | 9:1 | |

| 2000 CR105 | 3,304 | 221.59±0.16 | 5:1 | |

| 2012 VP113 | 4268±179 | 4,300 | 265.8±3.3 | 4:1 |

| 2004 VN112 | 5845±30 | 5,900 | 319.6±6.0 | 3:1 |

| 2010 GB174 | 7150±827 | 6,600 | 350.7±4.7 | 5:2 |

| 90377 Sedna | ≈ 11,400 | 506.84±0.51 | 3:2 | |

| Hypothetical planet | ≈ 17,000 | ≈ 665 | 1:1 |

Malhotra said that she remains agnostic about Planet Nine, but noted that she and her colleagues have found that the orbits of extremely distant KBOs seem tilted in a way that is difficult to otherwise explain. "The amount of warp we see is just crazy," she says. "To me, it's the most intriguing evidence for Planet Nine I've run across so far."[81]

Temporary or coincidental nature of clustering

Cory Shankman et al examined the consequences of a distant massive perturber on the TNOs used to infer the planet's existence. While they observed longitude of perihelion alignment in their simulations, they failed to produce the alignments in argument of perihelion. Their simulations for the Planet Nine scenario also predicted a larger reservoir of high-inclination TNOs, that should have been detected in existing surveys but are still unseen so far – suggesting there is a currently missing or unseen signature of Planet Nine. Based on their simulations, they conclude that the observed alignment in argument of perihelion in existing TNOs is a temporary phenomenon that is due to a coincidence, and they expect this unusual alignment to disappear as more objects are detected.[81][82][83] The results of the OSSOS survey suggest that the observed clustering is the result of a combination of observing bias and small number statistics. The OSSOS survey found no evidence for the ω clustering and that the orbits of objects it observed are statistically consistent with random.[84]

Subsequent efforts toward indirect detection

Cassini measurements of perturbations of Saturn

An analysis of Cassini data on Saturn's orbital residuals was inconsistent with Planet Nine being located with a true anomaly of −130° to −110° or −65° to 85°. The analysis, using Batygin and Brown's orbital parameters for Planet Nine, suggests that the lack of perturbations to Saturn's orbit is best explained if Planet Nine is located at a true anomaly of 117.8°+11°

−10°. At this location, Planet Nine would be approximately 630 AU from the Sun,[85] with right ascension close to 2h and declination close to −20°, in Cetus.[86] In contrast, if the putative planet is near aphelion it could be moving projected towards the area of the sky with boundaries: right ascension 3.0h to 5.5h and declination −1° to 6°.[87]

An improved mathematical analysis of Cassini data by astrophysicists Matthew Holman and Matthew Payne tightened the constraints on possible locations of Planet Nine. Holman and Payne intersected their preferred regions, based on Saturn's position measurements, with Batygin and Brown's dynamical constraints on Planet Nine's orbit. Holman and Payne concluded that Planet Nine is most likely to be located in an area of the sky near the constellation Cetus, at (RA, Dec)=(40°, −15°), and extending c. 20° in all directions. They recommend this area as high priority for an efficient observational campaign.[88]

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory has stated that according to their mission managers and orbit determination experts, the Cassini spacecraft is not experiencing unexplained deviations in its orbit around Saturn. William Folkner, a planetary scientist at JPL stated, "An undiscovered planet outside the orbit of Neptune, 10 times the mass of Earth, would affect the orbit of Saturn, not Cassini ... This could produce a signature in the measurements of Cassini while in orbit about Saturn if the planet was close enough to the sun. But we do not see any unexplained signature above the level of the measurement noise in Cassini data taken from 2004 to 2016."[89] Observations of Saturn's orbit neither prove nor disprove that Planet Nine exists. Rather, they suggest that Planet Nine could not be in certain sections of its proposed orbit because its gravity would cause a noticeable effect on Saturn's position, inconsistent with actual observations.

Analysis of Pluto's orbit

An analysis of Pluto's orbit by Matthew J. Holman and Matthew J. Payne found perturbations much larger than predicted by Batygin and Brown's proposed orbit for Planet Nine. Holman and Payne suggested three possible explanations. The data regarding Pluto's orbit could have significant systematic errors. There could be unmodeled mass in the Solar System, such as an undiscovered small planet in the range of 60–100 AU in addition to Planet Nine; this could help explain the Kuiper cliff. There could be a planet more massive or closer to the Sun instead of the planet predicted by Batygin and Brown.[88]

Optimal orbit if objects are in strong resonances

An analysis by Sarah Millholland and Gregory Laughlin indicates that the commensurabilities of the extreme TNOs is most likely to occur if Planet Nine has a semi-major axis of 654 AU. Beginning with this semi-major axis they determine that Planet Nine best maintains the anti-alignment of their orbits and a strong clustering of arguments of perihelion if it is near aphelion and has e ~ 0.5, inc ~ 30°, ω ~ 150°, Ω ~ 50° (the last differs from B&B's value of 90°). The favored location of Planet Nine is a right ascension of 30° - 50° and a declination of -20° - 20°. They also note that in their simulations the clustering of arguments of perihelion is almost always smaller than has been observed.[90]

Ascending nodes of extreme trans-Neptunian objects

In a paper by Carlos and Raul de la Fuente Marcos evidence is shown for a possible bimodal distribution of the nodal distances of the ETNOs. This correlation is unlikely to be the result of observational bias since it also appears in the nodal distribution of large semi-major axis centaurs and comets. If it is due to the extreme TNOs experiencing close approaches to Planet Nine, it is consistent with a planet with a semi-major axis of 300–400 AU.[91]

Orbits of nearly parabolic comets

An analysis of the orbits of comets with nearly parabolic orbits identifies five new comets with hyperbolic orbits that approach the nominal orbit of Planet Nine described in Batygin's and Brown's initial paper. If these orbits are hyperbolic due to close encounters with Planet Nine their analysis estimates that Planet Nine is currently near aphelion with a right ascension of 83° - 90° and a declination of 8° - 10°.[92] Scott Sheppard, who is skeptical of this analysis, notes that a lot of forces influence the orbits of comets.[81]

Search for additional extreme trans-Neptunian objects

Finding more objects would allow astronomers to make more accurate predictions about the orbit of the hypothesized planet.[93] The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, when it is completed in 2023, will be able to map the entire sky in just a few nights, providing more data on distant Kuiper belt objects that could both bolster evidence for Planet Nine and help pinpoint its current location.[74]

Batygin and Brown also predict a yet-to-be-discovered population of distant objects. These objects would have semi-major axes greater than 250 AU, but they would have lower eccentricities and orbits that would be aligned with that of Planet Nine. The larger perihelia of these objects would make them fainter and more difficult to detect than the anti-aligned objects.[1]

Newly discovered extreme trans-Neptunian objects include:

- 2013 SY99, another distant object spotted by the Outer Solar System Origins Survey, discussed by Michele Bannister at a March 2016 lecture hosted by the SETI Institute and the same was reported in October 2016 AAS conference.[94][95]

- 2013 FT28, located on the opposite side of the sky (Longitude of perihelion aligned with Planet Nine) – but well within the proposed orbit of Planet Nine, where computer modeling suggests it would be safe from gravitational kicks.[96]

- 2014 SR349, falling right in line with the earlier six objects.[96]

- 2014 FE72, an object with an orbit so extreme that it reaches about 3000 AU from the Sun in a massively-elongated ellipse – at this distance its orbit is influenced by the galactic tide and other stars.[97][98][99][100]

On June 19, 2017, an OSSOS preprint named 3 new bodies with semi-major axes beyond 250 AUs: 2015 GT50, 2015 RX245, 2015 KG163, along with 2013 SY99 which was announced last year.[101]

A systematic exploration by Carlos de la Fuente Marcos of commensurabilities (period ratios consistent with pairs of objects in resonance with each other) among the known ETNOs using Monte Carlo techniques revealed a pattern similar to the Kuiper belt, consistent with an additional planetary-sized object beyond Pluto.[102] If Planet Nine were on its nominal orbit and in the direction favored by the analysis of Cassini data, some objects like Sedna would remain on stable orbits while the orbits of others would become unstable leading to their ejection from the Solar System. Other possible orbits could leave all six of the objects identified by Batygin and Brown on stable orbits that maintain anti-alignment.[103] An analysis of the distributions of the directions of perihelia and orbital poles of the ETNOs also suggests that one additional planet may not be sufficient to to explain the observed clustering.[87]

Similarities between the orbit of 2013 RF98 and that of (474640) 2004 VN112 have led to the suggestion that they were a binary object disrupted near aphelion during an encounter with a distant object. The visible spectra of (474640) 2004 VN112 and 2013 RF98 are also similar but very different from that of 90377 Sedna. The value of their spectral slopes suggests that the surfaces of (474640) 2004 VN112 and 2013 RF98 can have pure methane ices (like in the case of Pluto) and highly processed carbons, including some amorphous silicates. Its spectral slope is similar to that of 2004 VN112.[104]

Other impacts

Solar obliquity

Analyses conducted contemporarily and independently by Bailey, Batygin and Brown, and by Gomes, Deienno and Morbidelli, and later by Lai suggest that Planet Nine could be responsible for inducing the spin–orbit misalignment of the Solar System. The Sun's axis of rotation is tilted approximately six degrees from the orbital plane of the giant planets. The exact reason for this discrepancy remains an open question in astronomy. The analysis used computer simulations to show that both the magnitude and direction of tilt can be explained by the gravitational torques exerted by Planet Nine on the other planets over the lifetime of the Solar System. These observations are consistent with the Planet Nine hypothesis, but do not prove that Planet Nine exists, as there could be some other reason, or more than one reason, for the spin–orbit misalignment of the Solar System.[105][106][107]

High inclination TNOs

A population of high inclination transneptunian objects with semi-major axes less than 100 AU is generated via the combined effects of Planet Nine and the other giant planets. Large semi-major axis objects that reach high inclination orbits due to the Kozai mechanism can have their perihelia lowered during this process bringing them onto orbits that intersect that of Neptune. Encounters with Neptune can then lower their semi-major axes to below 100 AU where their evolution is no longer controlled by Planet Nine. The orbital distribution of the longest lived of these objects is nonuniform. Most objects have orbits with perihelia ranging from 5 AU to 35 AU and inclinations below 110 degree, beyond a gap with few objects are others with inclinations near 150 degrees and perihelia near 10 AU.[68]

Planet Nine cloud

The dynamical effect of Planet Nine generates a cloud of objects with semi-major axes centered around Planet Nine's semi-major axis. In simulations with the planets in their current orbits the number of objects in high-perihelion and moderate semi-major axis orbits (q > 37 AU, 50 < a < 500 AU) is increased threefold with a distant planet in a circular orbit at 250 AU and tenfold if it is in an eccentric orbit with a semi-major axis of 500 AU. The cloud of objects has a wider inclination distribution, with a significant fraction having inclinations greater than 60°, if the distant planet has an eccentric orbit. However, because such distant objects are difficult to detect with current instruments and often not relocated, current surveys are as yet unable to distinguish between these possibilities.[82] Simulations of the giant planet migration described in the Nice model with Planet Nine in its nominal orbit yield similar results. Most objects in the Planet Nine cloud have semi-major axes greater than Planet Nine's and their inclinations extend up to 180 degrees. Roughly 0.3 – 0.4 Earth masses of an initial 20 Earth mass planetesimal disk remains in the cloud at the end of the simulation of the last 4 billion years.[108]

Effect on Oort cloud

An unpublished preprint by Technion doctoral student Erez Michaely and Harvard astronomy professor Avi Loeb has suggested that Planet Nine would lead to the formation of a spheroidal structure within the Oort cloud at approximately 1200 AU, which could be a source of comets and would differ from structure produced by a passing star. They suggested that the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope or Breakthrough Initiatives could detect this structure, if it exists.[109] Numerical simulations of the migration of the giant planets show that the number of objects captured in the Oort cloud is reduced if Planet Nine was in its predicted orbit at that time.[108] This reduction of objects captured in the Oort cloud also occurred in simulations with the giant planets on their current orbits.[82]

Direct detection

Location

If Planet Nine exists and is close to its perihelion, astronomers could identify it based on existing images. For its aphelion, the largest telescopes would be required. However, if the planet is currently located in between, many observatories could spot Planet Nine.[15] Statistically, the planet is more likely to be closer to its aphelion at a distance greater than 500 AU.[2] This is because objects move more slowly when near their aphelion, in accordance with Kepler's second law. The search in databases of stellar objects performed by Batygin and Brown has already excluded much of the sky the predicted planet could be in, save the direction of its aphelion, or in the difficult to spot backgrounds where the orbit crosses the plane of the Milky Way, where most stars lie.[19]

Radiation

A distant planet such as this would reflect little light, but, because it is hypothesized to be a large body, it would still be cooling from its formation with an estimated temperature of 47 K.[110] At this temperature the peak of its emissions would be at infrared wavelengths. This radiation signature could be detected by Earth-based infrared telescopes, such as ALMA,[111] and a search could be conducted by cosmic microwave background experiments operating at mm wavelengths.[112][113][M] Additionally, Jim Green of NASA is optimistic that the James Webb Space Telescope, which will be the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope and is expected to launch in 2018, could find it.[77]

Visibility

Telescopes are searching for the object, which, due to its extreme distance from the Sun, would reflect little sunlight and potentially evade telescope sightings.[6] It is expected to have an apparent magnitude fainter than 22, making it at least 600 times fainter than Pluto.[2][N]

Because the planet is predicted to be visible in the Northern Hemisphere, the primary search is expected to be carried out using the Subaru telescope, which has both an aperture large enough to see faint objects and a wide field of view to shorten the search.[41] Two teams of astronomers—Batygin and Brown, as well as Trujillo and Sheppard—are undertaking this search together, and both teams cooperatively expect the search to take up to five years.[13][118]

A preliminary search of the archival data from the Catalina Sky Survey to magnitude c. 19, Pan-STARRS to magnitude 21.5, and WISE has not identified Planet Nine.[2] The remaining areas to search are near aphelion, which is located close to the galactic plane of the Milky Way.[2] This aphelion direction is where the predicted planet would be faintest and has a complicated star-rich field of view in which to spot it.[19]

A zone around the constellation Cetus, where Cassini data suggest Planet Nine may be located, is being searched as of 2016[update] by the Dark Energy Survey—a project in the Southern Hemisphere designed to probe the acceleration of the Universe.[119] DES observes about 105 nights per season, lasting from August to February. Brown and Batygin initially narrowed it down to roughly 2,000 square degrees of sky near Orion, a swath of space, that in Batygin's opinion, could be covered in about 20 nights by the Subaru telescope.[120] Subsequent refinements by Batygin and Brown have reduced the search space to 600–800 square degrees of sky.[121] David Gerdes who helped develop the camera for USDOE claims that it is quite possible that one of the images taken for his galaxy map may actually contain a picture of Planet Nine, and if so, new software developed recently and used to identify objects such as 2014 UZ224 can help to find it.[122]

Citizen science

Zooniverse Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 project

The Zooniverse Backyard Worlds project, started in February 2017, is using archival data from the WISE spacecraft to search for Planet Nine. The project will additionally search for substellar objects like brown dwarfs in the neighborhood of the Solar System.[123][124]

Zooniverse SkyMapper project

In April 2017,[125] using data from the SkyMapper telescope at Siding Spring Observatory, citizen scientists on the Zooniverse platform reported four candidates for Planet Nine. These candidates will be followed up on by astronomers to determine their viability.[126] The project, which started on 28 March, completed their goals in less than three days with around five million classifications by more than 60,000 individuals.[126]

Origin

A number of possible origins for Planet Nine have been examined including its ejection from the neighborhood of the current giant planets, capture from another star, and in situ formation.

In their initial paper Batygin and Brown proposed that Planet Nine formed closer to the Sun and was ejected onto a distant eccentric orbit following a close encounter with Jupiter or Saturn during the nebular epoch.[1] Gravitational interactions with nearby stars in the Sun's birth cluster, or dynamical friction from the gaseous remnants of the solar nebula,[127] then reduced the eccentricity of its orbit, raising its perihelion, leaving it on a very wide but stable orbit.[71][128] Had it not been flung into the Solar System's farthest reaches, Planet Nine could have accreted more mass from the proto-planetary disk and developed into the core of a gas giant.[6] Instead, its growth was halted early, leaving it with a lower mass of five times Earth's mass, similar to that of Uranus and Neptune.[129] For Planet Nine to have been captured in a distant, stable orbit its ejection must have occurred early, between three million and ten million years after the formation of the Solar System.[13] This timing suggests that Planet Nine is not the planet ejected in a five-planet version of the Nice model, unless that occurred too early to be the cause of the Late Heavy Bombardment,[130] which would then require another explanation.[131] These ejections, however, are likely to have been two events well separated in time.[132]

Close encounters between the Sun and other stars in its birth cluster could have resulted in the capture of a planet from beyond the Solar System. Three-body interactions during these encounters can perturb the path of planets on distant orbits around another star or free-floating planets in a process similar to the capture of irregular satellites around the giant planets, leaving one in a stable orbit around the Sun. A planet that originated in a system with a number of Neptune-massed planets and without Jupiter-massed planets, could be scattered onto a more long-lasting distant eccentric orbit, increasing its chances of capture by another star.[7] Although this increases the odds of the Sun capturing another planet from another star, a wide variety of orbits are possible, reducing the probability of a planet being captured on an orbit like that proposed for Planet Nine to 1–2 percent.[9][133]

A planet could also be perturbed from a distant circular orbit into an eccentric orbit by an encounter with another star. The in situ formation of a planet at this distance would require a very massive and extensive disk,[1] or the outward drift of solids in a dissipating disk forming a narrow ring from which the planet accreted over a billion years.[8] If a planet formed at such a great distance while the Sun was in its birth cluster, the probability of it remaining bound to the Sun in a highly eccentric orbit is roughly 10%.[9]

Ethan Siegel, who is deeply skeptical of the existence of an undiscovered new planet in the Solar System, nevertheless speculates that at least one super-Earth, which have been commonly discovered in other planetary systems but have not been discovered in the Solar System, might have been ejected from the inner Solar System due to the inward migration of Jupiter in the early Solar System.[65][134] Hal Levison thinks that the chance of an ejected object ending up in the inner Oort cloud is only about 2%, and speculates that many objects must have been thrown past the Oort cloud if one has entered a stable orbit.[135]

Astronomers expect that the discovery of Planet Nine would aid in understanding the processes behind the formation of the Solar System and other planetary systems, as well as how unusual the Solar System is, with a lack of planets with masses between that of Earth and that of Neptune, compared to other planetary systems.[136]

See also

- History of Solar System formation and evolution hypotheses

- Hypothetical planets of the Solar System

- Kuiper belt

- (471325) 2011 KT19

- Nemesis (hypothetical star)

- Planets beyond Neptune

- Trans-Neptunian object

- Tyche (hypothetical planet)

- Discovery of Neptune

Notes

- ^ Most news outlets reported the name as Phattie (a slang term for "cool" or "awesome"; also, a marijuana cigarette)[13] but The New Yorker quote cited above uses "fatty" in what appears to be a nearly unique variation. The apparently correct spelling has been substituted.

- ^ The New Yorker put the average orbital distance of Planet Nine into perspective with an apparent allusion to one of the magazine's most famous cartoons, View of the World from 9th Avenue: "If the Sun were on Fifth Avenue and Earth were one block west, Jupiter would be on the West Side Highway, Pluto would be in Montclair, New Jersey, and the new planet would be somewhere near Cleveland.[5]"

- ^ Assuming that the orbital elements of these objects have not changed, Jilkova & co proposed an encounter with a passing star might have helped acquire these objects – dubbed sednitos (ETNOs with q > 30 and a > 150) by them. They also predicted that the sednitos region is populated by 930 planetesimals and the inner Oort Cloud acquired ∼440 planetesimals through the same encounter.[43][44]

- ^ In their paper Brown & Batygin note that "the lack of ω ~ 180 objects suggests that some additional process (such as encounter with a passing star) is required to account for the missing objects at 180°".

- ^ In their paper Brown & Batygin note that the fact that the ratio of the perturbed object to perturber semimajor axis is nearly equal to one "means that trapping all of the distant objects within the known range of semimajor axes into Kozai resonances likely requires multiple planets, finely tuned to explain the particular data set". Hence, they do not favor this theory, as they view it too unwieldy.

- ^ Two types of protection mechanisms are possible:[54]

- For bodies whose values of a and e are such that they could encounter the planets only near perihelion (or aphelion), such encounters may be prevented by the high inclination and the libration of ω about 90° or 270° (even when the encounters occur, they do not affect much the minor planet's orbit due to comparatively high relative velocities).

- Another mechanism is viable when at low inclinations when ω oscillates around 0° or 180° and the minor planet's semimajor axis is close to that of the perturbing planet: in this case the °node crossing occurs always near perihelion and aphelion, far from the planet itself, provided the eccentricity is high enough and the orbit of the planet is almost circular.

- ^ Given the orbital eccentricity of these objects, different epochs can generate quite different heliocentric unperturbed two-body best-fit solutions to the semi-major axis and orbital period. For objects at such high eccentricity, the Sun's barycenter is more stable than heliocentric values. Barycentric values better account for the changing position of Jupiter over Jupiter's 12 year orbit. As an example, 2007 TG422 has an epoch 2012 heliocentric period of ~13,500 years,[60] yet an epoch 2017 heliocentric period of ~10,400 years.[61] The barycentric solution is a much more stabe ~11,300 years.

- ^ Batygin & Brown provide an order of magnitude estimate for the mass.

- If M were equal to 0.1 ME, then the dynamical evolution would proceed at an exceptionally slow rate, and the lifetime of the Solar System would likely be insufficient for the required orbital sculpting to transpire.

- If M were equal to 1 ME, then long-lived apsidally anti-aligned orbits would indeed occur, but removal of unstable orbits would happen on a much longer timescale than the current evolution of the Solar System. Hence, even though they would show preference for a particular apsidal direction, they would not exhibit true confinement like the data.

- They also note that M greater than 10 ME would imply a longer semi-major axis.

- ^ Fixing of the orbital plane requires a combination of two parameters: inclination and longitude of the ascending node. The average of longitude of the ascending node for the 6 objects is about 102°. In a paper published later, Batygin and Brown constrained their estimate of the longitude of the ascending node to 91°±15°.

- ^ It has been noted that the clustering initially observed was tighter than predicted in simulations including Planet Nine.[62] In the companion paper the chance of observing the combination of strong anti-alignment beyond 250 AU, weak alignment between 100 AU and 200 AU, and no objects with semi-major axes between 100 AU and 200 AU and perihelia beyond 42 AU was less than 10%. Since the acceptance of the companion paper new objects have been identified that are not anti-aligned (2013 FT28, 2015 KG163, and 2015 GT50) and others with perihelia beyond 42 AU and semi-major axes between 100-200 AU (2014 SS349 and 2013 UT15)

- ^ In a paper submitted to The Astronomical Journal in July 2016, Scott S. Sheppard & Chad Trujillo suggest that a new object 2013 FT28 falls under this category of objects.[46][69][70]

- ^ In their paper Brown & Batygin note that "the vast majority of this (primordial planetesimal disk) material was ejected from the system by close encounters with the giant planets during, and immediately following, the transient dynamical instability that shaped the Kuiper Belt in the first place. The characteristic timescale for depletion of the primordial disk is likely to be short compared with the timescale for the onset of the inclination instability (Nesvorný 2015), calling into question whether the inclination instability could have actually proceeded in the outer solar system."

- ^ It is estimated that to find Planet Nine, telescopes that can resolve a 30 mJy point source are needed, and that can also resolve an annual parallax motion of ~5 arcminutes per year.[114]

- ^ The 8-meter Subaru telescope has achieved a 27.7 magnitude photographic limit with a ten-hour exposure,[115] which is about 100 times dimmer than Planet Nine is expected to be. For comparison, the Hubble Space Telescope has detected objects as faint as 31st magnitude with an exposure of about 2 million seconds (555 hours) during Hubble Ultra Deep Field photography.[116] However, Hubble's field of view is very narrow, as is the Keck Observatory Large Binocular Telescope.[13] Brown hopes to make a request for use of the Hubble Space Telescope the day the planet is spotted.[117]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Batygin, Konstantin; Brown, Michael E. (2016). "Evidence for a distant giant planet in the Solar system". The Astronomical Journal. 151 (2): 22. arXiv:1601.05438. Bibcode:2016AJ....151...22B. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/151/2/22.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Where is Planet Nine?". The Search for Planet Nine. 20 January 2016. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Witze, Alexandra (2016). "Evidence grows for giant planet on fringes of Solar System". Nature. 529 (7586): 266–7. Bibcode:2016Natur.529..266W. doi:10.1038/529266a. PMID 26791699.

- ^ a b c d e Trujillo, Chadwick A.; Sheppard, Scott S. (2014). "A Sedna-like body with a perihelion of 80 astronomical units" (PDF). Nature. 507 (7493): 471–4. Bibcode:2014Natur.507..471T. doi:10.1038/nature13156. PMID 24670765.

- ^ a b c d e Burdick, Alan (20 January 2016). "Discovering Planet Nine". The New Yorker. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Achenbach, Joel; Feltman, Rachel (20 January 2016). "New evidence suggests a ninth planet lurking at the edge of the solar system". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ a b Raymond, Sean (30 March 2016). "Planet Nine from Outer Space!". PlanetPlanet.net. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ a b Kenyon, Scott J.; Bromley, Benjamin C. (2016). "Making Planet Nine: Pebble Accretion at 250–750 AU in a Gravitationally Unstable Ring". The Astrophysical Journal. 825 (1): 33. arXiv:1603.08008. Bibcode:2016ApJ...825...33K. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/825/1/33.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Li, Gongjie; Adams, Fred C. (2016). "Interaction Cross Sections and Survival Rates for Proposed Solar System Member Planet Nine". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 823 (1): L3. arXiv:1602.08496. Bibcode:2016ApJ...823L...3L. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/823/1/L3.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Naming of Astronomical Objects". International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ Totten, Sanden (22 January 2016). "Planet 9: What should its name be if it's found?". 89.3 KPCC. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

'We like to be consistent,' said Rosaly Lopes, a senior research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and a member of the IAU's Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature. ... For a planet in our solar system, being consistent means sticking to the theme of giving them names from Greek and Roman mythology.

- ^ a b c d Batygin, Konstantin (19 January 2016). "Search for Planet 9 – Premonition". The Search for Planet Nine. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Hand, Eric (20 January 2016). "Astronomers say a Neptune-sized planet lurks beyond Pluto". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aae0237. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ Caltech Observatory (29 January 2016). "Planet 9 Explained and Explored with Astronomer Konstantin Batygin". YouTube. 2:22.

- ^ a b c d Fesenmaier, Kimm (20 January 2016). "Caltech Researchers Find Evidence of a Real Ninth Planet". California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ Drake, Nadia (20 January 2016). "Scientists Find Evidence for Ninth Planet in Solar System". National Geographic. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- ^ Plait, Phil (21 January 2016). "More (and Best Yet) Evidence That Another Planet Lurks in the Dark Depths of Our Solar System". Bad Astronomy. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

The best fit was for a planet that never got closer than 200 AU from the Sun (... Neptune is roughly 30 AU out from the Sun). The orbit of this planet would be highly elliptical, but it's not clear how elliptical; that's less well constrained. At its most distant, it could be between 500 and 1,200 AU out ... The most likely mass of the planet is about 10 times Earth's mass ..., though it could be somewhat less or more.

- ^ Michael E. Brown (3 March 2017). "Planet Nine". YouTube. 19:06.

- ^ a b c See RA/Dec chart at Batygin, Konstantin; Brown, Mike (20 January 2016). "Where is Planet Nine?". The Search for Planet Nine. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ See embedded video simulation at Lemonick, Michael D. (20 January 2016). "Strong Evidence Suggests a Super Earth Lies beyond Pluto". Scientific American. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ Becker, Adam; Grossman, Lisa; Aron, Jacob (22 January 2016). "How Planet Nine may have been exiled to solar system's edge". New Scientist. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ Williams, David R. (18 November 2015). "Planetary Fact Sheet - Ratio to Earth". NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ Watson, Traci (20 January 2016). "Researchers find evidence of ninth planet in solar system". USA Today. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (27 August 2009). "The Planetary Society Blog: "WISE Guys"". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- ^ Luhman, Kevin L. (2014). "A search for a distant companion to the Sun with the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer". The Astrophysical Journal. 781 (4): 4. Bibcode:2014ApJ...781....4L. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/781/1/4.

- ^ a b Brown, Mike (19 January 2016). "Is Planet Nine a "planet"?". The Search for Planet Nine. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Margot, Jean-Luc (22 January 2016). "Would Planet Nine Pass the Planet Test?". University of California at Los Angeles. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ Wall, Mike (24 August 2011). "A Conversation With Pluto's Killer: Q & A With Astronomer Mike Brown". Space.com. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Brown, Micheal E.; Trujillo, Chadwick; Rabinowitz, David (2004). "Discovery of a Candidate Inner Oort Cloud Planetoid". The Astrophysical Journal. 617 (1): 645–649. arXiv:astro-ph/0404456. Bibcode:2004ApJ...617..645B. doi:10.1086/422095.

- ^ Brown, Michael E. (28 October 2010). "There's something out there – part 2". Mike Brown's Planets. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ Patryk S., Lykawka; Tadashi, Mukai (2008). "An Outer Planet Beyond Pluto and the Origin of the Trans-Neptunian Belt Architecture". The Astronomical Journal. 135 (4): 1161–1200. arXiv:0712.2198. Bibcode:2008AJ....135.1161L. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/4/1161.

- ^ Ryall, Julie (17 March 2008). "Earth-Size Planet to Be Found in Outer Solar System?". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ Than, Ker (18 June 2008). "Large 'Planet X' May Lurk Beyond Pluto". Space.com. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ Hasegawa, Kyoko (28 February 2008). "Japanese scientists eye mysterious 'Planet X'". BibliotecaPleyades.net. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ Gomes, Rodney S.; Soares, J. S. (8 May 2012). Signatures Of A Putative Planetary Mass Solar Companion On The Orbital Distribution Of Tno's And Centaurs. American Astronomical Society, DDA meeting #43, id.5.01. Bibcode:2012DDA....43.0501G.

- ^ Wolchover, Natalie (25 May 2012). "Planet X? New Evidence of an Unseen Planet at Solar System's Edge". LiveScience. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

More work is needed to determine whether Sedna and the other scattered disc objects were sent on their circuitous trips round the sun by a star that passed by long ago, or by an unseen planet that exists in the solar system right now. Finding and observing the orbits of other distant objects similar to Sedna will add more data points to astronomers' computer models.

- ^ Lovett, Richard A. (12 May 2012). "New Planet Found in Our Solar System?". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ Gomes, Rodney (2015). "The observation of large semi-major axis Centaurs: Testing for the signature of a planetary-mass solar companion". Icarus. 258: 37–49. Bibcode:2015Icar..258...37G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.06.020.

- ^ Brown, Mike (24 January 2016). "The long and winding history of Planet X".

- ^ Sample, Ian (26 March 2014). "Dwarf planet discovery hints at a hidden Super Earth in solar system". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ a b Mortillaro, Nicole (9 February 2016). "Meet Mike Brown: Pluto killer and the man who brought us Planet 9". Global News.

'It was that search for more objects like Sedna ... led to the realization ... that they're all being pulled off in one direction by something. And that's what finally led us down the hole that there must be a big planet out there.' – Mike Brown

- ^ a b c Crocket, Christopher (14 November 2014). "A distant planet may lurk far beyond Neptune". Science News. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jílková, Lucie; Portegies Zwart, Simon; Pijloo, Tjibaria; Hammer, Michael (2015). "How Sedna and family were captured in a close encounter with a solar sibling". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 453 (3): 3157–3162. arXiv:1506.03105. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.453.3157J. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv1803.

- ^ Dickinson, David (6 August 2015). "Stealing Sedna". Universe Today. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ a b de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (2014). "Extreme trans-Neptunian objects and the Kozai mechanism: signalling the presence of trans-Plutonian planets". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters. 443 (1): L59–L63. arXiv:1406.0715. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.443L..59D. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slu084.

- ^ a b Sheppard, Scott; Trujillo, Chad (2016). "New Extreme Trans-Neptunian Objects: Towards a Super-Earth in the Outer Solar System". The Astronomical Journal. 152 (6): 221. arXiv:1608.08772. Bibcode:2016AJ....152..221S. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/152/6/221.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Rzetelny, Xaq (21 January 2015). "The Solar System may have two undiscovered planets". Ars Technica. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl; Aarseth, Sverre J. (2014). "Flipping minor bodies: what comet 96P/Machholz 1 can tell us about the orbital evolution of extreme trans-Neptunian objects and the production of near-Earth objects on retrograde orbits". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 446 (2): 1867–187. arXiv:1410.6307. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.446.1867D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2230.

- ^ Jenner, Nicola (11 June 2014). "Two giant planets may cruise unseen beyond Pluto". New Scientist. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Lemonick, Michael D. (19 January 2015). "There May Be 'Super Earths' at the Edge of Our Solar System". Time. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Wall, Mike (16 January 2015). "Mysterious Planet X May Really Lurk Undiscovered in Our Solar System". Space.com. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy (15 January 2015). "Astronomers are predicting at least two more large planets in the solar system". Universe Today. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Gilster, Paul (16 January 2015). "Planets to Be Discovered in the Outer System?". CentauriDreams.org. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Koponyás, Barbara (10 April 2010). "Near-Earth asteroids and the Kozai-mechanism" (PDF). 5th Austrian Hungarian Workshop in Vienna. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ McDonald, Bob (24 January 2016). "How did we miss Planet 9?". CBC News. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

It's like seeing a disturbance on the surface of water but not knowing what caused it. Perhaps it was a jumping fish, a whale or a seal. Even though you didn't actually see it, you could make an informed guess about the size of the object and its location by the nature of the ripples in the water.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (20 January 2016). "Theoretical evidence for an undiscovered super-Earth at the edge of our solar system". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ a b "MPC list of q > 30 and a > 250". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ a b Grush, Loren (20 January 2016). "Our solar system may have a ninth planet after all — but not all evidence is in (We still haven't seen it yet)". The Verge. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

The statistics do sound promising, at first. The researchers say there's a 1 in 15,000 chance that the movements of these objects are coincidental and don't indicate a planetary presence at all. ... 'When we usually consider something as clinched and air tight, it usually has odds with a much lower probability of failure than what they have,' says Sara Seager, a planetary scientist at MIT. For a study to be a slam dunk, the odds of failure are usually 1 in 1,744,278. ... But researchers often publish before they get the slam-dunk odds, in order to avoid getting scooped by a competing team, Seager says. Most outside experts agree that the researchers' models are strong. And Neptune was originally detected in a similar fashion — by researching observed anomalies in the movement of Uranus. Additionally, the idea of a large planet at such a distance from the Sun isn't actually that unlikely, according to Bruce Macintosh, a planetary scientist at Stanford University.

- ^ a b Brown, Michael; Batygin, Konstantin (2016). "Observational constraints on the orbit and location of Planet Nine in the outer Solar System". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. arXiv:1603.05712. Bibcode:2016ApJ...824L..23B. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/824/2/L23.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Browser". 13 December 2012. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chamberlin, Alan. "JPL Small-Body Database Browser". ssd.jpl.nasa.gov.

- ^ Batygin, Konstantin. "Status Update (Part 1)". The Search for Planet Nine. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ Batygin, Konstantin (24 July 2016). "Pathway to Planet Nine". Physics World. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ^ Hruska, Joel (20 January 2016). "Our solar system may contain a ninth planet, far beyond Pluto". ExtremeTech. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ a b Siegel, Ethan (20 January 2016). "Not So Fast: Why There Likely Isn't A Large Planet Beyond Pluto". Forbes. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ a b "MPC list of a > 250, i > 40, and q > 6". Minor Planet Center.

- ^ Brown, Mike (12 February 2016). "Why I believe in Planet Nine". The Search for Planet Nine. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ a b Batygin, Konstantin; Brown, Michael E. (2016). "Generation of Highly Inclined Trans-Neptunian Objects by Planet Nine". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 833 (1): L3. arXiv:1610.04992. Bibcode:2016ApJ...833L...3B. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/833/1/L3.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "The hunt for Planet Nine reveals some strange, far-out objects".

2013 FT28, has a strange mix of characteristics that could mean its orbit still responds too much to Neptune's tug to be helpful in the search.

- ^ "Hunt for ninth planet reveals new extremely distant Solar System objects".

2013 FT28 shows similar clustering in some of these parameters (its semi-major axis, eccentricity, inclination, and argument of perihelion angle, for angle enthusiasts out there) but one of these parameters, an angle called the longitude of perihelion, is different from that of the other extreme objects, which makes that particular clustering trend less strong

- ^ a b Chang, Kenneth (20 January 2016). "Ninth Planet May Exist Beyond Pluto, Scientists Report". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ Kiss, Cs.; Szabó, Gy.; Horner, J.; Conn, B. C.; Müller, T. G.; Vilenius, E.; Sárneczky, K.; Kiss, L. L.; Bannister, M.; Bayliss, D.; Pál, A.; Góbi, S.; Verebélyi, E.; Lellouch, E.; Santos-Sanz, P.; Ortiz, J. L.; Duffard, R.; Morales, N. (2013). "A portrait of the extreme solar system object 2012 DR30". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 555: A3. arXiv:1304.7112. Bibcode:2013A&A...555A...3K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321147.

- ^ a b Levenson, Thomas (25 January 2016). "A New Planet or a Red Herring?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

'We plotted the real data on top of the model' Batyagin recalls, and they fell 'exactly where they were supposed to be.' That was, he said, the epiphany. 'It was a dramatic moment. This thing I thought could disprove it turned out to be the strongest evidence for Planet Nine.'

- ^ a b Allen, Kate (20 January 2016). "Is a real ninth planet out there beyond Pluto?". The Toronto Star. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ Crocket, Christopher (31 January 2016). "Computer simulations heat up hunt for Planet Nine". Science News. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

'It's exciting and very compelling work,' says Meg Schwamb, a planetary scientist at Academia Sinica in Taipei, Taiwan. But only six bodies lead the way to the putative planet. 'Whether that's enough is still a question.'

- ^ "We can't see this possible 9th planet, but we feel its presence". PBS NewsHour. 22 January 2016. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

'Right now, any good scientist is going to be skeptical, because it's a pretty big claim. And without the final evidence that it's real, there is always that chance that it's not. So, everybody should be skeptical. But I think it's time to mount this search. I mean, we like to think of it as, we have provided the treasure map of where this ninth planet is, and we have done the starting gun, and now it's a race to actually point your telescope at the right spot in the sky and make that discovery of planet nine.' – Mike Brown

- ^ a b Fecht, Sarah (22 January 2016). "Can there really be a planet in our solar system that we don't know about?". Popular Science. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ Snell, Jason (5 February 2016). "This Week in Space: Weird Pluto and No Plan for Mars". Yahoo! Tech. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ Wall, Mike (4 February 2016). "'Planet Nine'? Cosmic Objects' Strange Orbits May Have a Different Explanation". Space.com.

We need more mass in the outer solar system," she (Madigan) said. "So it can either come from having more minor planets, and their self-gravity will do this to themselves naturally, or it could be in the form of one single massive planet — a Planet Nine. So it's a really exciting time, and we're going to discover one or the other.

- ^ a b Malhotra, Renu; Volk, Kathryn; Wang, Xianyu (2016). "Corralling a distant planet with extreme resonant Kuiper belt objects". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 824 (2): L22. arXiv:1603.02196. Bibcode:2016ApJ...824L..22M. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/824/2/L22.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Choi, Charles Q. (25 October 2016). "Closing in on a Giant Ghost Planet". Scientific American. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ^ a b c Lawler, S. M.; Shankman, C.; Kaib, N.; Bannister, M. T.; Gladman, B.; Kavelaars, J. J. (29 December 2016) [21 May 2016]. "Observational Signatures of a Massive Distant Planet on the Scattering Disk". The Astronomical Journal. 153 (1): 33. arXiv:1605.06575. Bibcode:2017AJ....153...33L. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/153/1/33.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Shankman, Cory; Kavelaars, J. J.; Lawler, Samantha; Bannister, Michelle (2017). "Consequences of a distant massive planet on the large semi-major axis trans-Neptunian objects". The Astronomical Journal. 153 (2): 63. arXiv:1610.04251. Bibcode:2017AJ....153...63S. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/153/2/63.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.05348 OSSOS VI. Striking Biases in the detection of large semimajor axis Trans-Neptunian Objects

- ^ Fienga, A.; Laskar, J.; Manche, H.; Gastineau, M. (2016). "Constraints on the location of a possible 9th planet derived from the Cassini data". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 587 (1): L8. arXiv:1602.06116. Bibcode:2016A&A...587L...8F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201628227.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (2016). "Finding Planet Nine: a Monte Carlo approach". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters. 459 (1): L66–L70. arXiv:1603.06520. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.459L..66D. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slw049.

- ^ a b de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (2016). "Finding Planet Nine: apsidal anti-alignment Monte Carlo results". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 462 (2): 1972–1977. arXiv:1607.05633. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.462.1972D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1778.

- ^ a b Holman, Matthew J.; Payne, Matthew J. (9 September 2016). "Observational Constraints on Planet Nine: Astrometry of Pluto and Other Trans-Neptunian Objects". The Astronomical Journal. 152 (4): 80. arXiv:1603.09008. Bibcode:2016AJ....152...80H. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/152/4/80.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Saturn Spacecraft Not Affected by Hypothetical Planet 9". NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 8 April 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ Millholland, Sarah; Laughlin, Gregory (2017). "Constraints on Planet Nine's Orbit and Sky Position within a Framework of Mean-motion Resonances". The Astronomical Journal. 153 (3): 91. arXiv:1612.07774. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/153/3/91.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (2017). "Evidence for a possible bimodal distribution of the nodal distances of the extreme trans-Neptunian objects: avoiding a trans-Plutonian planet or just plain bias?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters. arXiv:1706.06981. Bibcode:2017arXiv170606981D. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slx106.