1 Timothy 2:12

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity and gender |

|---|

|

1 Timothy 2:12 is the twelfth verse of the second chapter of the First Epistle to Timothy. It is often quoted using the King James Version translation:

But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence.

— 1 Timothy 2:12, KJV[1]

The verse is widely used to oppose ordination of women as clergy, and to oppose certain other positions of ministry and leadership for women in large segments of Christianity. Many such groups that do not permit women to become clergy also cite 1 Corinthians 14:32–35[2] and 1 Timothy 3:1–7.[3] Historically, the verse was used to justify legal inequality for women and to exclude women from secular leadership roles as well.

For most of the history of Christian theology the verse has been interpreted to require some degree of subordination of women to men. Some theologians, like Ambrosiaster in the 4th century and John Knox in the 16th century, wrote that it requires very strict domination of women in every sphere of life. Others, like John Chrysostom and Martin Luther, write that it excludes women from teaching, praying, or speaking in public but grants some freedom to women in the home.

The verse has been criticized for its sexism and its perceived inconsistency with other verses attributed to Paul, such as Galatians 3:28, which states "there is neither male nor female, for ye are all one in Christ Jesus." Richard and Catherine Kroeger point to examples of female teachers and leaders known to Paul, such as Priscilla and Phoebe, to support their conclusion that the verse has been mistranslated. Most modern scholars believe 1 Timothy was not actually written by Paul.

Today, some scholars argue that the instruction is directed to the particular church in Ephesus and must be interpreted in a contemporary context. Others interpret the text as a universal instruction. Christian egalitarians maintain that there should be no institutional distinctions between men and women. Complementarians argue that the instructions contained in 1 Timothy 2:12 should be accepted as normative in the church today.

Authorship

[edit]The traditional view is that the words "I suffer not a woman..." are Paul's own words, along with the rest of the epistle. A minority of modern scholars, such as Catherine Kroeger, support this traditional view.

Bart Ehrman’s view is that a large majority of modern scholars of 1 Timothy epistle believe it was not written by Paul, but dates to after Paul's death and has an unknown author.[4][5] As a pseudepigraphical work incorrectly attributed to Paul, the verse is often described as deutero-Pauline literature[6] or as a pastoral epistle.

New Testament scholar Marcus Borg contends that this verse fits poorly with Paul's more positive references to Christian women and may be a later interpolation rather than part of the original text.[7]

Use

[edit]In his 4th century Latin commentary on the epistles, Ambrosiaster viewed 1 Timothy 2:12 as requiring a strict system of patriarchy. He writes that women "were put under the power of men from the beginning" and should be severely subjugated to men.[8] Ambrosiaster's strictly patriarchal understanding was copied by Glossa Ordinaria and most other medieval interpretations of the verse in the Latin Church. In the Greek-speaking church, John Chrysostom wrote that the verse prohibits women from teaching the public or making public speeches.[8]

The verse was widely used to oppose all education for women, and all teaching by women, during the Renaissance and early modern period in Europe. It was cited frequently by those who wished to condemn women or believed them inferior to men.[9] Ambrosiaster and 1 Timothy 2:12 were cited by John Knox in The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstruous Regiment of Women, a 1558 book attacking the idea of rule by queens and women in leadership on biblical grounds.[10]

Martin Luther wrote that "man" in this verse specifically refers to a husband, meaning that wives should never appear wiser or more knowledgeable than their husbands, neither in public nor at home. Luther contends that, because of this verse and nearby verses in 1 Timothy, women should not speak or teach in public and must remain completely quiet in church, writing "where there is a man, there no woman should teach or have authority."[11] On this basis, parts of Lutheranism today do not allow women into church leadership.

Female theologians faced a dilemma in staying true to this scripture while acting as teachers. Teresa of Ávila wrote that women must teach through their actions because they were both prohibited from and incapable of teaching with words. Though she did produce theological writing, she was careful to efface herself as foolish and weak.[12]

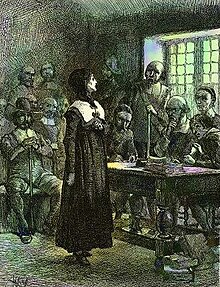

During the 1637 trial of Anne Hutchinson for illegal theological teaching, magistrate John Winthrop (who was both Hutchinson's accuser and the judge in her trial) admonished Hutchinson with 1 Timothy 2:12, demanding her silence because he felt she was too outspoken in defending herself.[13]

In the 19th century the verse was frequently employed to justify the inferior legal status of women. For example, Meyrick Goulburn argued the verse clearly excludes women from all public offices or roles, including secular ones, and that women are only fit for domestic labor.[14]

Today it is still used to exclude women from religious education or teaching. For example, Southern Baptist institutions in the United States have fired women teachers because of the verse.[15] The verse is used in excluding women from the Catholic priesthood and is considered by Catholics to prohibit women from performing priest-like teaching roles, such as giving homilies.[16]

Interpretive approaches

[edit]Complementarian and egalitarian

[edit]N. T. Wright, former Bishop of Durham, says that 1 Timothy 2 is the "hardest passage of all" to exegete properly.[17] A number of interpretive approaches to the text have been made by both complementarians and egalitarians. The 1 Timothy 2:12 passage is only one "side" of a letter written by Paul, and is directed at a particular group. Therefore, interpretations are limited to one-sided information with no record of the associated correspondence to which Paul was responding. Theologian Philip Payne, a Cambridge PhD and former Tübingen scholar, is convinced that 1 Timothy 2:12 is the only New Testament verse that "might" explicitly prohibit women from teaching or having authority over men, though he writes that he does not think that is what it means.[18] Moore maintains that "Any interpretation of these portions of Scripture must wrestle with the theological, contextual, syntactical, and lexical difficulties embedded within these few words".[19][full citation needed]

Wheaton scholar and professor Gilbert Bilezikian concludes that although it may seem that Paul is laying down an ordinance that has the character of a universal norm for all Christians in all ages, that view does not survive close scrutiny. After extensive research, he has reached these conclusions:

- That the apostle Paul wrote this epistle to a church that was in a state of terminal crisis;

- That Paul drastically curtailed the ministries of both women and men to save the Church at Ephesus from what he terms as a high risk of "self-destruction";

- That the restrictions Paul laid down in this epistle were temporary measures of exception designed to prevent this one particular church from disintegration;

- That the remedial crisis-management provisions mandated in this passage remain valid for all times for churches that fall into similar states of dysfunction.[20]

Bilezikian concludes that the exceptional character of the emergency measures advocated by Paul serves as evidence that women could indeed teach and hold leadership positions under normal circumstances.

Egalitarian and complementarian interpretive approaches to the text typically take the following forms:

- Socio-cultural: Egalitarians argue that the text was intended for a specific socio-cultural environment which no longer exists and that the text is therefore not relevant to modern churches[21] (typically rely heavily on historical reconstructions using extra-biblical sources); complementarians argue that the socio-cultural environment, while relevant, does not restrict the application of the verse to a specific time and place in the past.[22]

- Lexical: Egalitarians argue that the meaning of the key word in the text, authenteō, does not support the exclusion of women from authoritative teaching positions in the congregation;[23] Complementarians argue that the meaning of this word in its context indicates that Paul was forbidding women from having authority over men in the church.[24]

- Hermeneutical: Some egalitarians argue that the text was intended only to limit women for a specific temporary duration, or that it was intended only to limit uneducated women who were unfit to speak in the congregation;[25] Complementarians argue that hermeneutical considerations indicate the text is universal in its application to Christian congregations[26]

Socio-cultural

[edit]Christian Egalitarians believe that the passage does not carry the same meaning for the modern church when interpreted in light of the socio-cultural situation of Paul's time; that a key word in the passage should be reinterpreted to mean something other than "exercising authority". Some recent scholarship is believed to show that Paul never intended his first letter to Timothy to apply to the church at all times and places. Instead, it was intended to remediate a state of acute crisis being created by a "massive influx of false teaching and cultic intrusions" threatening the survival of the very young Church at Ephesus.[20]

The egalitarian socio-cultural position has been represented prominently by classicist Catherine Kroeger and theologian Richard Kroeger. They believe the author of 1 Timothy was refuting false teaching, rather than establishing a narrow restriction on women's role. The Kroegers maintain that Paul was uniquely addressing the Ephesian situation because of its feminist religious culture where women had usurped religious authority over men. They cite a wide range of primary sources to support their case that the Ephesian women were teaching a particular Gnostic notion concerning Eve. They point out that women routinely teach and lead men in the New Testament: Lois and Eunice taught Timothy, Priscilla taught Apollos, and Phoebe was a church deacon.[21]

However, their conclusions have been rejected by certain historians[27] as well as by some complementarians. I. H. Marshall cautions that "It is precarious, as Edwin Yamauchi and others have shown, to assume Gnostic backgrounds for New Testament books. Although the phrase, 'falsely called knowledge', in 1 Timothy 6:20 contains the Greek word gnosis, this was the common word for 'knowledge'. It does seem anachronistic to transliterate and capitalize it 'Gnosis' as the Kroegers do. They thus explain verse 13 as an answer to the false notion that the woman is the originator of man with the Artemis cult in Ephesus that had somehow crept into the church, possibly by way of the false teaching. However, this explanation cannot be substantiated (except from later Gnostic writings)".[28] Streland concludes that "Kroeger and Kroeger stand alone in their interpretation".[29][30]

According to Thomas Schreiner, "The full-fledged Gnosticism of later church history did not exist in the first century 21 AD. An incipient form of Gnosticism was present, but Schmithals makes the error of reading later Gnosticism into the first century documents. Richard and Catherine Kroeger follow in Schmithals's[31] footsteps in positing the background to 1 Timothy 2:12. They call the heresy 'proto-Gnostic', but in fact they often appeal to later sources to define the false teaching (v.23). External evidence can only be admitted if it can be shown that the religious or philosophical movement was contemporary with the New Testament".[32] In his critique of the Kroegers' book, J. M. Holmes' opinion is that "As a classicist [...] [Catherine Kroeger]'s own contributions are reconstruction of a background and choices from linguistic options viewed as appropriate to that background. Both have been discredited".[33]: p.26

Many contemporary advocates of Christian Egalitarianism do find considerable value in the Kroegers' research.[34] Catherine Kroeger, in one of her articles, points out that authentein is a rare Greek verb found only here in the entire Bible. She writes that in extra-biblical literature—the only other places it can be found, the word is ordinarily translated 'to bear rule' or 'to usurp authority'. Yet, a study of other Greek literary sources reveals that it did not ordinarily have this meaning until the third or fourth century, well after the time of the New Testament. Prior to and during Paul's time, the rare uses of the word included references to murder, suicide, 'one who slays with his own hand', and 'self-murderer'. Moeris, in the second century, advised his students to use another word, autodikein, as it was less coarse than authentein. The Byzantine Thomas Magister reiterates the warning against using the term, calling it "objectionable".[35][36] Kroeger writes that St. John Chrysostom, in his Commentary on I Timothy 5.6, uses autheritia to denote 'sexual license'. He argues that too often the seriousness of this problem for the New Testament church is underestimated, and concludes that it is evident that a similar heresy is current at Ephesus, where these false teachers "worm(ed) their way into homes and gain control over gullible women, who are loaded down with sins and are swayed by all kinds of evil desires, always learning but never able to come to a knowledge of the truth" (2 Timothy 3:6–9).[37]

Concluding that the author of 1 Timothy was addressing a specific situation that was a serious threat to the infant, fragile church, in an article entitled "1 Timothy 2:11–15: Anti-Gnostic Measures against Women"[38] the author writes that the "tragedy is that these verses were extensively used in later tradition to justify contemporary prejudices against women. They were supposed to prove from the inspired Scriptures that God subjected women to men and that women are more susceptible to temptation and deception".

Trombley and Newport agree that the Kroegers rightly indicate that authenteo had meanings connected with sex acts and murder in extra-biblical literature. They find it consistent with the historical context of the first letter to Timothy, at the church in Ephesus—home to the goddess Diana's shrine where worship involved ritual sex and sacrifice.[36][39]

Lexical

[edit]Catherine Kroeger has been one of the major proponents of egalitarian lexical arguments that the key word in the text, authenteō, does not support the exclusion of women from authoritative teaching positions in the congregation. In 1979 Kroeger asserted the meaning of the word was 'to engage in fertility practices',[23] but this was not universally accepted by scholars, complementarian or egalitarian.[40] "Kroeger and Kroeger have done significant research into the nature and background of ancient Ephesus and have suggested an alternative interpretation to 1 Tim 2:11–15. While they have provided significant background data, their suggestion that the phrase 'to have authority' (authentein, authentein) [sic?] should be rendered 'to represent herself as originator of man' is, to say the least, far-fetched and has gained little support".[41] "On the basis of outdated lexicography, uncited and no longer extant classical texts, a discredited background (see my Introduction n. 25), and the introduction of an ellipsis into a clause which is itself complete, the Kroegers rewrite v. 12".[33]: p. 89 Details of lexical and syntactical studies into the meaning of authente by both egalitarians and complementarians are found further down in this article.

Hermeneutical

[edit]Egalitarians Aida Spencer and Wheaton New Testament scholar Gilbert Bilezikian have argued that the prohibition on women speaking in the congregation was only intended to be a temporary response to women who were teaching error.

Bilezikian points out that the word translated as 'authority' in 1 Timothy 2:12, one that is a key proof text used to keep women out of church leadership, is a word used only here and never used again anywhere in Scripture. He writes that the word translated "authority" in that passage is a hapax legomenon, a word that appears only once within the structure of the Bible and never cross-referenced again. He says one should "never build a doctrine on or draw a teaching from an unclear or debated hapax". Therefore, since there is no "control text" to determine its meaning, Bilezikian asserts that no one knows for sure what the word means and what exactly Paul is forbidding. He adds that there is "so much clear non-hapaxic material available in the Bible that we do not need to press into service difficult texts that are better left aside when not understood. [...] We are accountable only for that which we can understand".[42]: p. 20

Spencer notes that rather than using the imperative mood or even an aorist or future indicative to express that prohibition, Paul quite significantly utilizes a present indicative, perhaps best rendered "But I am not presently allowing". Spencer believes this is a temporary prohibition that is based solely on the regrettable similarity between the Ephesian women and Eve—in that the women of Ephesus had been deceived and as such, if allowed to teach, would be in danger of promoting false doctrine.[43]

Spencer's argument has been criticized by complementarian authors and at least one egalitarian writer.[44]

Barron points out that defenders of the traditional view have argued that Paul's blanket statement, "I do not permit a woman to teach", sounds universal. He asks if what Paul really meant was "I do not permit a woman to teach error", and that if he would have no objection to women teaching once they got their doctrine straight, questions why he did not say this.[45]

Gorden Fee, an egalitarian scholar, also has difficulty with Spencer's hermeneutical points. Fee says that despite protests to the contrary, Paul states the "rule" itself absolutely—without any form of qualification. Therefore, he finds it difficult to interpret this as meaning anything else than all forms of speaking out in churches.[46][47]

Although he proposes an updated scenario in his 2006 version of Beyond Sex Roles, Gilbert Bilezikian in his 1989 version proposed that Paul may have been distinguishing between qualified, trained teachers and some of the unschooled women who struggled to assert themselves as teachers with their newly found freedom in Christianity.[48] However, this view is opposed by egalitarians B. Barron[49] and Gordon Fee.[50] Bilezikian further suggests that the fledgling church at Ephesus had been formed among confrontations of superstitious, occult practices.[48] This view is opposed by egalitarians such as Walter Liefeld,[51] as well as by complementarians such as Schreiner.[52] Bilezikian proposes that "the solution for proper understanding of this passage is to follow its development to the letter":

Women in Ephesus should first become learners,v.11 and quit acting as teachers or assuming the authority of recognized teachers.v.12 Just as Eve rather than Adam was deceived into error, unqualified persons will get themselves and the church in trouble.vv.13–14 Yet, as Eve became the means and the first beneficiary of promised salvation, so Ephesian women will legitimately aspire to maturity and competency and to positions of service in the church.v.15

— Gilbert Bilezikian[48] : p. 183

Feminist

[edit]The Woman's Bible, a 19th-century feminist reexamination of the bible, criticized the passage as sexist. Contributor Lucinda Banister Chandler writes that the prohibition of women from teaching is "tyrannical" considering that a large proportion of classroom teachers are women, and that teaching is an important part of motherhood.[53]

Chandler finds the verse strikingly inconsistent with Galatians 3:28, also attributed to Paul, which states "There is neither Jew nor Greek, bond nor free, male or female, but ye are one in Christ Jesus." She observes that there is no similar statement by Jesus that woman should be subject to man or refrain from teaching.[53]

British women's rights activist Annie Besant points to this verse (among others) to observe that women are treated as slaves in the Bible. She considers this the root of the unequal and paternalistic way in which women were treated during her own lifetime. Besant finds the explanation given in Timothy for the inferiority of women — that men are superior because Adam was created before Eve — to be absurd, implying that animals are superior to man, as the Bible states that animals were created even earlier.[54]

Meaning of authenteō

[edit]The meaning of the word authentein (authenteō) in verse 12 has been the source of considerable differences of opinion among biblical scholars in recent decades. The first is that the lexical history of this word is long and complex. Walter Liefeld describes briefly the word's problematically broad semantic range:

A perplexing issue for all is the meaning of authentein. Over the course of its history this verb and its associated noun have had a wide semantic range, including some bizarre meanings, such as committing suicide, murdering one's parents, and being sexually aggressive. Some studies have been marred by a selective and improper use of the evidence.[55]

Classical Greek

[edit]The standard lexical reference work for classical Greek, the Liddell Scott Greek Lexicon has the following entry for the verb authentein:

αὐθεντ-έω, A. to have full power or authority over, τινός 1st Epistle to Timothy 2.12; "πρός τινα" Berliner griechische Urkunden BGU1208.37(i B.C.): c. inf. Joannes Laurentius Lydus Lyd.Mag.3.42. 2. commit a murder, Scholia to Aeschylus Eumenides 42.[56]

An exhaustive listing of all incidences is found in Köstenberger's appendix. Then the following related entry for the noun authentes:

αὐθέντ-ης, ου, ὁ, (cf. αὐτοέντης) A. murderer, Herodotus.1.117, Euripides Rhesus.873, Thucydides.3.58; "τινός" Euripides Hercules Furens.1359, Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica.2.754; suicide, Antiphon (person) 3.3.4, Dio Cassius.37.13: more loosely, one of a murderer's family, Euripides Andromache.172. 2. perpetrator, author, "πράξεως" Polybius.22.14.2; "ἱεροσυλίας" Diodorus Siculus.16.61: generally, doer, Alexander Rhetor.p.2S.; master, "δῆμος αὐθέντης χθονός" Euripides The Suppliants.442; voc. "αὐθέντα ἥλιε" Leiden Magical Papyrus W.6.46 [in A. Dieterich, Leipzig 1891]; condemned by Phrynichus Attistica.96. 3. as Adjective, ὅμαιμος αυφόνος, αὐ. φάνατοι, murder by one of the same family, Aeschylus Eumenides.212, Agamemnon.1572 (lyr.). (For αὐτο-ἕντης, cf. συν-έντης, ἁνύω; root sen-, sṇ-.)[abbreviations expanded for legibility][57][58]

Then the noun-form authentia, 'authority':

αὐθεντ-ία, ἡ, A. absolute sway, authority, Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum CIG2701.9 (Mylasa), PLips (L. Mitteis, Griechische Urkunden der Papyrussammlung zu Leipzig, vol. i, 1906).37.7 (iv A. D.), Corpus Hermeticum.1.2, Zosimus Epigrammaticus (Anthologia Graeca).2.33. 2. restriction, LXX 3 Maccabees.2.29. 3. "αὐθεντίᾳ ἀποκτείνας" with his own hand, Dio Cassius.Fr.102.12.[59]

Bible translations

[edit]The issue is compounded by the fact that this word is found only once in the New Testament, and is not common in immediately proximate Greek literature. Nevertheless, English Bible translations over the years have been generally in agreement when rendering the word. In the translations below, the words corresponding to authenteō are in emphasised:

- Greek New Testament: "γυναικὶ δὲ διδάσκειν οὐκ ἐπιτρέπω, οὐδὲ αὐθεντεῖν ἀνδρός, ἀλλ᾽ εἶναι ἐν ἡσυχίᾳ"

- Vulgate: "docere autem mulieri non permitto, neque dominari in virum, sed esse in silentio"

- KJV: "But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence."

- RSV: "I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over men; she is to keep silent."

- GNB: "I do not allow them to teach or to have authority over men; they must keep quiet."

- NIV: "I do not permit a woman to teach or to have authority over a man; she must be silent."

- CEV: "They should be silent and not be allowed to teach or to tell men what to do."

- NASB: "But I do not allow a woman to teach or exercise authority over a man, but to remain quiet."

- NLT: "I do not let women teach men or have authority over them. Let them listen quietly."

- NET: "But I do not allow a woman to teach or exercise authority over a man. She must remain quiet."

Gender bias

[edit]Elizabeth A. McCabe has identified and documented evidence of gender bias in English translations of the Bible that do not apply exclusively to the word authentein. Greek words indicating that women held positions of authority in the church also appear to have been altered in translation. Women identified in Greek manuscripts as a diakonos ('deacon') or prostatis ('leader') are referred to as servants in some English translations, like the King James Version. This is inconsistent with the manner in which these words are typically translated regarding men.[60]

Furthermore, if this translation of authentein is accepted without consideration of contextual factors related to the stated context of the original letter (e.g., challenges facing Timothy at the church in Ephesus),[a] it appears to contradict other biblical passages in which women are clearly depicted as leading or teaching:

Now Deborah, a prophet, the wife of Lappidoth, was leading Israel at that time. She held court under the Palm of Deborah between Ramah and Bethel in the hill country of Ephraim, and the Israelites went up to her to have their disputes decided.

— Judges 4:4–5[61]

I commend to you our sister Phoebe, a servant of the church in Cenchreae. I ask you to receive her in the Lord in a way worthy of his people and to give her any help she may need from you, for she has been the benefactor of many people, including me.

— Romans 16:1–3[62]

Catherine Kroeger

[edit]Examples of the use of authentein in extra-biblical sources have been provided by Catherine Kroeger:

Although the usages prior to and during the New Testament period are few and far between, they are briefs of murder cases and once to mean suicide, as did Dio Cassius. Thucydides, Herodotus, and Aeschylus also use the word to denote one who slays with his own hand, and so does Euripides. The Jewish Philo, whose writings are contemporary with the New Testament, meant 'self-murderer' by his use of the term.

In Euripides the word begins to take on a sexual tinge. Menelaos is accounted a murderer because of his wife's malfeasance, and Andromache, the adored wife of the fallen Hector, is taken as a concubine by the authentes, who can command her domestic and sexual services. In fury the legitimate wife castigates Andromache with sexually abusive terms as "having the effrontery to sleep with the son of the father who destroyed your husband, in order to bear the child of an authentes". In the extended passage she mingles the concepts of incest and domestic murder, so that love and death color the meaning.

In a lengthy description of various tribes' sexual habits, Michael Glycas, the Byzantine historiographer, uses this verb to describe women "who make sexual advances to men and fornicate as much as they please without arousing their husbands' jealousy".

Licentious doctrines continued to vex the church for several centuries, to the dismay of the church fathers. Clement of Alexandria wrote a detailed refutation of the various groups who endorsed fornication as accepted Christian behavior. He complained of those who had turned love-feasts into sex orgies, of those who taught women to "give to every man that asketh of thee", and of those who found in physical intercourse a "mystical communion". He branded one such lewd group authentai (the plural of authentes).[35]

The meaning of the word was seriously disputed in 1979 when Catherine Kroeger, then a university classics student, asserted the meaning was "to engage in fertility practices". Kroeger cites the findings of French linguist and noted authority on Greek philology, Pierre Chantraine to support her conclusions.[63][64]

In later work, Kroeger explored other possible meanings of the word authentein that are consistent with its use in Greek literature prior to and during the New Testament era. In 1992, she highlighted the possibility that authentein is a reference to ritual violence perpetrated against men in the goddess worship of Asia Minor. Specifically, she focused on the practice of ritual castration as a rite of purification for priests of Artemis and Cybele.[65] A. H. Jones, J. Ferguson, and A. R. Favazza all highlight the prevalence of ritual castration in Asia Minor before, during and after the New Testament era.[66][67][68] In 1 Timothy 1:3–7 and 4:1–5, the author of the epistle warns against false teaching, mythology and extreme forms of asceticism. Ritual castration was part of an extreme form of asceticism practiced in and around Ephesus during the New Testament period, and evidence presented by Favazza suggests that it did have an influence on the emerging traditions of the early Christian church.[68]

Leland E. Wilshire in 2010 made a study of the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae database, which contains 329 references to variations of the word authentein in Greek literature, and concluded that authentein in the New Testament period, in Ephesus of Asia Minor, most likely refers to some form of violence.[69] Wilshire does not make a definitive statement regarding the nature of the violence the epistle may be referring to, but notes that authentein was often used to express the commission of violence, murder or suicide.

Responses

[edit]Although the claim was rejected largely by complementarian scholars, debate over the meaning of the word had been opened, and Christians affirming an egalitarian view of the role of women in the church continued to contest the meaning of the word authenteō.[70] Standard lexicons including authenteō are broadly in agreement with regard to its historical lexical range.[71][72][73][74][75] Wilshire, however, documents that whereas lexicons such as the Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literauture only contain 13 examples of the word authetein and its cognates, the computer database known as the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (TLG) contains 329 examples, offering a much larger and more representative sample of the use of the word throughout the history of Greek literature.[76] Uses of the word in the TLG from 200 BC to 200 AD are listed in a subsequent section below—syntactical study.

A number of key studies of authenteō have been undertaken over the last 30 years,[timeframe?] some of which have involved comprehensive searches of the largest available databases of Greek literature, Thesaurus Linguae Graecae, and the Duke Databank of Documentary Papyri. These databases enable researchers to study the word in context, as it is used in a wide range of documents over a long period of time.

- Catherine Kroeger (1979)[23]

- George Knight III (1984)[77]

- Leland Wilshire (1988)[78]

- Catherine and Richard Kroeger (1992)[79]

- Andrew Perriman (1993)[80]

- H. Scott Baldwin (1995)[81]

- Andreas J. Köstenberger (1995)[82]

- Albert Wolters (2000)[83]

- Linda Belleville (2004)[84]

Those who favor "traditional" understandings of male ecclesiastical leadership have tended to translate this word in the neutral sense of "have authority" or "exercise authority" as, for example, George Knight in his widely cited article of 1984. In 1988, Leland Wilshire, examining 329 occurrences of this word and its cognate authentēs, claimed that, prior to and contemporary with the 1st century, authentein often had negative overtones such as 'domineer', 'perpetrate a crime' or even 'murder'. Not until the later patristic period did the meaning 'to exercise authority' come to predominate.

By 2000, Scott Baldwin's study of the word was considered the most extensive, demonstrating that the meaning in a given passage must be determined by context. "After extended debate, the most thorough lexical study is undoubtedly that of H. Scott Baldwin, who conclusively demonstrates that various shades of meaning are possible, and that only the context can determine which is intended".[33]: pp.86–87 Linda Belleville's later study examined the five occurrences of authentei as a verb or noun prior to or contemporary with Paul and rendered these texts as follows: "commit acts of violence";[85] "the author of a message";[86] a letter of Tryphon (1st century BC), which Belleville rendered "I had my way with him"; the poet Dorotheus (1st and 2nd centuries AD) in an astrological text, rendered by Bellville "Saturn [...] dominates Mercury". Belleville maintains that it is clear in these that a neutral meaning such as "have authority" is not in view. Her study has been criticized for treating the infinitive authentein as a noun, which is considered a major weakness in her argument.[87]

Lexical studies have been particularly focused on two early papyri; Papyrus BGU 1208 (c. 27 BC), using the verb authenteō and speaking of Trypho exercising his authority, and Papyrus Tebtunis 15 (c. 100 AD), using the noun form and speaking of bookkeepers having authority over their accounts. These two papyri are significant not only because they are closest in time to Paul's own usage of authenteō, but because they both use their respective words with a sense which is generally held to be in agreement with the studies by Baldwin and Wolters, though some egalitarians (such as Linda Belleville), dispute the interpretation of authenteō in Papyrus BGU 1208.[84]

Syntactical study

[edit]The lexical data was later supplemented by a large scale contextual syntax study of the passage by Andreas Köstenberger in 1995,[82] which argued that the syntactical construction ouk didaskein oude authentein ("not teach nor have/exercise authority") requires that both didaskein and authentein have a positive sense. Köstenbereger examined fifty-two examples of the same ouk ... oude ("not... nor"), construction in the New Testament, as well as forty eight extra-biblical examples covering the 3rd century BC to the 3rd century AD. Köstenberger concluded that teaching has a positive meaning in such passages as 1 Timothy 4:12,[88] 6:2,[89] and 2:2.[90] The force of the ouk ... oude construction therefore would mean that authenteo likewise has a positive meaning, and does not refer to domineering but the positive exercise of authority.

The majority of complementarian and some egalitarian scholars agreed with Köstenberger, many considering that he had determined conclusively the contextual meaning of authenteo in 1 Timothy 2:12. Peter O'Brien, in a review published in Australia, concurred with the findings of this study, as did Helge Stadelmann in an extensive review that appeared in the German Jahrbuch für evangelikale Theologie. Both reviewers accepted the results of the present study as valid.[91] Köstenberger notes a range of egalitarians agreeing with his syntactical analysis. Kevin Giles "finds himself in essential agreement with the present syntactical analysis of 1 Tim 2:12",[91]: 48–49 Craig Blomberg is quoted as saying "Decisively supporting the more positive sense of assuming appropriate authority is Andreas Köstenberger's study".[91]: 49 Esther Ng continues, "However, since a negative connotation of didaskein is unlikely in this verse, the neutral meaning for authentein (to have authority over) seems to fit the oude construction better".[92] Egalitarian Craig Keener, in a review appearing in the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, states that while in his view the principle is not clear in all instances cited in Köstenberger's study, "the pattern seems to hold in general, and this is what matters most". Keener concurs that the contention of the present essay is "probably correct that 'have authority' should be read as coordinate with 'teach' rather than as subordinate ('teach in a domineering way')".[91]: 47

Egalitarians such as Wilshire (2010), however, reject the conclusion that authentein, as used in 1 Timothy 2:12, refers to the use of authority at all—either in a positive or negative sense.[93] Wilshire concludes that authentein might best be translated 'to instigate violence'.[94] Women in Timothy's congregation, therefore, are to neither teach nor instigate violence. He bases this conclusion upon a study of every known use of the word authentein (and its cognates) in Greek literature from the years 200 BC to 200 AD. This study was completed using the Thesaurus Linguae Graeca computer database. His findings are summarized as follows:

- Polybius used the word authenten, 2nd century BC, to mean 'the doer of a massacre'.

- The word authentian is used in 3 Macabees, 1st century BC, to mean 'restrictions' or 'rights'.

- Diodorus Siculus used three variations of the words (authentais, authenten, authentas), 1st century BC to 1st century AD, to mean 'perpetrators of sacrilege', 'author of crimes' and 'supporters of violent actions'.

- Philo Judaeus used the word authentes, 1st century BC to 1st century AD, to mean 'being one's own murderer'.

- Flavius Josephus used the words authenten and authentas, 1st century AD, to mean 'perpetrator of a crime' and 'perpetrators of a slaughter'.

- The apostle Paul used the word authentein once during the same time period as Diodorus, Philo and Josephus.

- Appian of Alexander used the word authentai three times, and the word authenten twice, 2nd century AD, to mean 'murderers', 'slayer', 'slayers of themselves' and 'perpetrators of evil'.

- Sim. of the Shepherd of Hermas used the word authentes, 2nd century AD, to mean 'builder of a tower'.

- A homily by Pseudo-Clement used the word authentes once, unknown date AD, to mean 'sole power'.

- Irenaeus used the word authenias three times, 2nd century AD, to mean 'authority'.

- Harpocration used the word authentes, 2nd century AD, to mean 'murderer'.

- Phrynichus used the word authentes once, 2nd century AD, to mean 'one who murders by his own hand'.

Whereas the word authentein was used on rare occasions (e.g. by Irenaeus) to denote authority, it was much more commonly used to indicate something violent, murderous or suicidal.[95]

Author and Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies at the University of California, Birger A. Pearson, shares historical information highlighting that the apostle Paul's use of the verb authentein in 1 Timothy 2:12 occurs in the same context (and the same century) as Philo's use of its noun cognate, authentes. In both instances, these words are found in the context of warnings against what scholars refer to as "false gnosis."[96] While Paul warns against "vain babblings" and "false knowledge" (1 Timothy 6:20), Philo warns against "vain opinions" and "falsehood."[97]

In the case of Philo, authentes is used to indicate that those who embrace false gnosis become responsible for the death of their own souls.[98] As context is essential for determining syntactic meaning in Koine Greek,[99] Pearson's work on historical context complements Wilshire's findings, that the meaning of authentein may be related to 'murder', or in this case 'responsibility for spiritual death', in conjunction with teaching false gnosis. Strengthening this case further, Pearson highlights that teachers of false gnosis were typically compared to the biblical figure of Cain, in 1st and 2nd century CE Jewish and Christian literature.[100] Cain is depicted in the Bible's book of Genesis (4:1–16) as humanity's first "murderer."

Meaning of didaskō

[edit]In 2014, John Dickson has questioned the meaning of the word didaskō ('teach'). Dickson argues that it refers to "preserving and laying down the traditions handed on by the apostles". Dickson goes on to argue that since that does not happen in most sermons today, women are not prohibited from giving sermons.[101] Dickson's argument has been criticized in Women, Sermons and the Bible: Essays interacting with John Dickson's Hearing Her Voice, published by Matthias Media.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Though the letter is traditionally held to have been written by the Apostle Paul (c. 5–c. 64/65 AD) to his younger colleague and delegate Timothy (c. 30 AD–c. 97 AD) regarding his ministry in Ephesus (1:3), most modern scholars consider the pastoral epistle to have been written after Paul's death (and potentially after Timothy's death as well). The epistle is generally dated to between the late 1st century and first half of the 2nd century AD.

References

[edit]- ^ 1 Timothy 2:12

- ^ 1 Corinthians 14:32–35

- ^ 1 Timothy 3:1–7

- ^ Ehrman, Bart (2003). 'The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. Oxford University Press. p. 393. ISBN 0-19-515462-2.

when we come to the Pastoral epistles, there is greater scholarly unanimity. These three letters are widely regarded by scholars as non-Pauline.

- ^ Collins, Raymond F. (2004). 1 & 2 Timothy and Titus: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-664-22247-1.

By the end of the twentieth century New Testament scholarship was virtually unanimous in affirming that the Pastoral Epistles were written some time after Paul's death. [...] As always some scholars dissent from the consensus view.

- ^ Horgan, M.P. "Deutero-Pauline Literature". New Catholic Encyclopedia. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Borg, Marcus J. and John Dominic Crossan. The First Paul. HarperOne. 2009. ISBN 978-0-06-180340-6

- ^ a b Wilshire, Leland E. (2010). Insight Into Two Biblical Passages: Anatomy of a Prohibition I Timothy 2:12, the TLG Computer, and the Christian Church. Plymouth: University Press of America. pp. 63–64. ISBN 9780761852087.

- ^ Brown, Meg Lota; McBride, Kari Boyd (2005). Women's Roles in the Renaissance. Greenwood Press. pp. 19–20, 49. ISBN 9780313322105.

- ^ Knox, John (1995). Selected Writings of John Knox: Public Epistles, Treatises, and Expositions to the Year 1559. Dallas, Texas: Presbyterian Heritage Publications. OCLC 33126638.

- ^ Luther, Martin (25 May 2016). "Commentary on 1 Timothy 2:9-14".

- ^ Allen, Prudence (2017). The Concept of Woman. Vol. 3. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 95–96. ISBN 9781467445931.

- ^ LaPlante, Eve (2010). American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the Puritans. Zondervan. p. 40. ISBN 9780061926952. OCLC 255776203.

- ^ Goulburn, Edward Meyrick (January 8, 1882). The sphere and duties of Christian women. p. 9.

- ^ Anderson, Cheryl (16 November 2009). Ancient Laws and Contemporary Controversies: The Need for Inclusive Biblical Interpretation. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 5. ISBN 9780195305500.

- ^ Nash, Tom. "Is 1 Timothy 2:8-15 Anti-Woman?". Catholic Answers.

- ^ Wright, N. T. "[www2.cbeinternational.org/CBE_InfoPack/pdf/wright_biblical_basis.pdf The Biblical Basis for Women's Service in the Church]". Accessed 16 December 2009

- ^ Payne, Philip B. Man and Woman, One in Christ: An Exegetical and Theological Study of Paul's Letters. Zondervan, 2009. ISBN 978-0-310-21988-0

- ^ Moore, Terri D. "Chapter Six: Conclusions on 1 Timothy 2:15". bible.org 30 October 2009.

- ^ a b Bilezikian, Gilbert. Beyond Sex Roles (2006 ed.) Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic, 2006. ISBN 978-0-8010-3153-3

- ^ a b Kroeger, Richard and Catherine Kroeger. "I Suffer Not a Woman: Rethinking 1 Timothy 2:11–15 in Light of Ancient Evidence". Baker, 1992. ISBN 978-0-8010-5250-7

- ^ Schreiner "Interpreting the Pauline Epistles", Southern Baptist Journal of Theology (3.3.10), (Fall 1999)

- ^ a b c Lutheran Church Missouri Synod Commission on Theology and Church Relations, "AUTHENTEIN: A Summary", pp. 3–4 (2005)

- ^ Andreas J. Köstenberger, "Women in the Church: An Analysis and Application of 1 Timothy 2:9–15" (1995).

- ^ Hugenberger, "Women In Church Office: Hermeneutics Or Exegesis? A Survey Of Approaches To 1 Tim 2:8–15", Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society (35.3.349), (September 1992)

- ^ Schreiner, "Paul, Apostle of God's Glory in Christ", p. 408 (2006)

- ^ Oster, Richard E. "Review of I Suffer Not a Woman. Rethinking 1 Timothy 2:11–15 in Light of Ancient Evidence by Richard Clark Kroeger and Catherine Clark Kroeger", in Biblical Archaeologist (56:4.226), Nomadic Pastoralism: Past and Present (December 1993). He further elucidates that "The Kroegers' thesis about the Pastorals also requires a large and syncretistic Jewish presence in Ephesus. Erroneous information is set forth to buttress this view. The assertion, for example, that 'archaeological evidence attests not only the presence of a large settlement of Jews at Ephesus but also to extensive Jewish involvement in magic' (p. 55) is patently false [...] Lamentably, their use of this work is characterized by misunderstanding and a serious inflation of the evidence [...] The most serious issue of methodology in I Suffer Not a Woman is the authors' frequent neglect of primary sources of Ephesian archaeology and history. It is perplexing that the Kroegers' views about Ephesus, about Artemis, and about the role of women in the city's life are so uninformed by the appropriate corpora of inscriptions, coins, and scholarly literature about the city's excavations. Even when the authors do employ primary sources, their methodology is often uncritical. The Kroegers often string sources together even when these are separated by centuries and perhaps hundreds of miles. On occasion ancient literature is cited with little regard for the propensities of the author or the context in which the statements were made. Proof-texting of pagan authors should be just as unacceptable as proof-texting of the Scriptures".

- ^ Marshall, I. Howard. "A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Pastoral Epistles", International Critical Commentary. Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2004. ISBN 978-0-567-08455-2. p. 463 (1999)

- ^ Strelan, Paul, Artemis, and the Jews in Ephesus (Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der älteren Kirche). Walter De Gruyter, 1996. p. 155

- ^ Lucinda A. Brown, in Carol Meyers; Toni Craven(Editor); Ross Shepard Kraemer (Eds.) Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2001. pp. 488–489

- ^ Schmithals, Walter. The Theology of the First Christians. Westminster John Knox Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-664-25615-9

- ^ Schreiner, Thomas R. "Interpreting the Pauline Epistles", Southern Baptist Journal of Theology (3.3.10), (Fall 1999)

- ^ a b c Holmes, J. M. Text in a Whirlwind: A Critique of Four Exegetical Devices at 1 Timothy 2.9–15 (Library of New Testament Studies). T&T Clark, 2000. ISBN 978-1-84127-121-7

- ^ Edwards, B. (2011). Let My People Go: A Call to End the Oppression of Women in the Church. Charleston, South Carolina: Createspace. ISBN 978-1-4664-0111-2

- ^ a b "The Meaning of Authentein". godswordtowomen.org.

- ^ a b Trombley, C. (2003) "Who Said Women Can't Teach?" Gainesville, Florida: Bridge-Logos. ISBN 0-88270-584-9

- ^ 2 Timothy 3:6–9

- ^ [1] Archived 2008-09-05 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 7 May 2013

- ^ Newport, J. P. (1988). The New Age Movement and the Biblical Worldview. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdman's Publishing Co. ISBN 0-8028-4430-8

- ^ "It is no wonder that L. E. Wilshire, even though he shares the egalitarian outlook, says: 'This is a breathtaking extension into (pre-)Gnostic content yet an interpretation I do not find supported either by the totality of their own extensive philological study, by the NT context, or by the immediate usages of the word authenteo and its variants'"., Baugh, "The Apostle among the Amazons", Westminster Theological Journal (56.157), (Spring 1994)

- ^ Moss, C. Michael. 1, 2 Timothy and Titus (College Pr NIV Commentary). College Press Publishing Company, 1994. p. 60

- ^ Bilezikian, Gilbert. Christianity 101. Zondervan, Grand Rapids, Michigan. 1993.

- ^ Hugenberger, Gordon P. "Women In Church Office: Hermeneutics Or Exegesis? A Survey of Approaches to 1 Tim 2:8–15", Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society (35.3.349), (September 1992)

- ^ "As attractive as this interpretation appears, serious objections have been raised against it in recent years. First of all, some caution may need to be exercised against an overly simplistic picture of the Jewish or Greek cultural background at times assumed for our passage. For example, Eunice and Lois (2 Tim. 1:5; 3:15) appear to have known the Scriptures better than might be inferred from the Jewish practice adduced by Spencer, although Spencer acknowledges the possibility that women could learn privately". Hugenberger, Gordon P. "Women In Church Office: Hermeneutics Or Exegesis? A Survey Of Approaches To 1 Tim 2:8–15", Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society (35.3.349), (September 1992)

- ^ Barron, B. "Putting Women in Their Place: 1 Timothy 2 and Evangelical Views of Women in Church Leadership", Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society (33.4.455), (December 1990)

- ^ Fee, Gordon D. The First Epistle to the Corinthians (The New International Commentary on the New Testament), p. 706 (1987)

- ^ Walter Liefeld raises further questions. "However, in the only passage in the Pastoral Epistles that combines a clear reference both to heretical teachings and to women, women are not the promulgators but the victims of false teaching (2 Tim 3:6-7). The question still remains, therefore, why Paul does not leave matters with the general prohibition against false teaching in 1 Timothy 1:3–4, but adds a paragraph directed specifically against women teachers. He thus restricts the recipients, rather than the originators, of the false doctrine. Of course, since the women—whether because of poor education, pagan influence or whatever—were being easily deceived in that culture, that fact connects with the reference in 2:14 to the deceiving of Eve. But that relates to the problem of women being deceived rather than to the problem of heresy itself".Liefeld, Walter (1986). Response to David M. Scholer", in Mickelsen, Alvera. Women, authority & the Bible. IVP Books. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-87784-608-6.

- ^ a b c Bilezikian, Gilbert. Beyond Sex Roles. Baker Book House, 1989.

- ^ "Not all women of Paul's day were intellectually impoverished or hopelessly contaminated by pagan practices, yet Paul seems to prohibit all women from teaching in Ephesus. The egalitarians seem forced into the implausible claim that no woman in the Ephesian church was sufficiently orthodox and educated to teach". Barron, C. (December 1990). "Putting Women in Their Place: 1 Timothy 2 and Evangelical Views of Women in Church Leadership". Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society. 33 (4): 455–456.

- ^ "If authentic, this unqualified use of the verb seems to tell against the probability that only a single form of speech is prohibited. Elsewhere Paul has said 'speak in tongues' when that is in view, and when he means 'discern' he says 'discern', not 'speak'. Again, as with the opening 'rule', the plain sense of the sentence is an absolute prohibition of all speaking in the assembly". Fee, Gordon (1987). The First Epistle to the Corinthians (The New International Commentary on the New Testament). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 706–707. ISBN 978-0-8028-2507-0.

- ^ "However, in the only passage in the Pastoral Epistles that combines a clear reference both to heretical teachings and to women, women are not the promulgators but the victims of false teaching (2 Tim 3:6–7). The question still remains, therefore, why Paul does not leave matters with the general prohibition against false teaching in 1 Timothy 1:3–4, but adds a paragraph directed specifically against women teachers". Liefeld, Walter (1986). "Response to David M. Scholer". In Mickelsen, Alvera (ed.). Women, authority & the Bible. IVP Books. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-87784-608-6.

- ^ "It is not hard to imagine Paul writing, 'I do not permit a woman to teach or exercise authority over a man... because women are uneducated'. Nor would it be difficult for Paul to say that women cannot teach 'because they are spreading false teaching'. Nothing close to either of these two points is communicated". Schreiner, Thomas R. (2006). Paul, Apostle of God's Glory in Christ: A Pauline Theology. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-2825-8.

- ^ a b Stanton, Elizabeth Cady (1898). "Epistles to Timothy". The Woman's Bible. Vol. Part II.

- ^ Besant, Annie (1885). Woman's Position According to the Bible. A. Besant and C. Bradlaugh. pp. 2–3.

- ^ Liefeld, "Women And The Nature Of Ministry", Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society (30:51), (1987)

- ^ LSJ verb αὐθεντ-έω

- ^ LSJ noun αὐθέντ-ης

- ^ Henry George Liddell; Robert Scott. "αὐθέντ-ρια". A Greek-English Lexicon. tufts.edu.

- ^ LSJ noun αὐθεντία

- ^ SBL Forum. "A Reexamination of Phoebe as a 'Diakonos' and 'Prostatis': Exposing the Inaccuracies of English Translations"

- ^ Judges 4:4–5

- ^ Romans 16:1–3

- ^ Kroeger, C. (1986) 1 Timothy 2:12, A Classicist's View. In A. Mickelsen (Ed.), Women, Authority & the Bible, pp. 225–243. Downer's Grove, Illinois: Intervarsity Press.

- ^ Deidre Richardson (28 October 2009). "Men and Women in the Church". womeninthechurch-junia.blogspot.ca.

- ^ Kroeger, C. and Kroeger, R. (1992). I Suffer Not a Woman: Rethinking 1 Timothy 2:11–15 in Light of Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House.

- ^ Jones, A. H. (1985). Essenes: The elect of Israel and the priests of Artemis. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America, Inc.

- ^ Ferguson, J. (1970). The religions of the Roman Empire. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- ^ a b Favazza, A. R. (2011). Bodies under siege: self-mutilation, nonsuicidal self-injury, and body modification in culture and psychiatry. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Wilshire, L. E. (2010). Insight into Two Biblical Passages. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America

- ^ "During the past two decades at least 15 studies examining in some detail the lexical data have appeared, mainly among evangelical scholars holding opposing positions on the role of women in the church (commonly referred to as a debate of complementarians vs egalitarians)", Lutheran Church Missouri Synod, Commission on Theology and Church Relations "AUTHENTEIN: A Summary", p. 3 (2005)

- ^ Arndt, Danker and Bauer, A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature, p. 150 (3rd ed., 2000)

- ^ Balz & Schneider, Exegetical dictionary of the New Testament. Translation of: Exegetisches Wörterbuch zum Neuen Testamen, volume 1, p. 178 (1990–c1993)

- ^ Lust, Eynikel, and Hauspie, A Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint (electronic rev. ed. 2003)

- ^ Newman, Concise Greek-English Dictionary of the New Testament, p. 28 (1993)

- ^ Swanson, Dictionary of Biblical Languages with Semantic Domains: Greek (New Testament), DBLG 883 (2nd ed. 2001)

- ^ Wilshire, L. E. (2010). Insight into Two Biblical Passages (p.17). Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America

- ^ House, A Biblical View of Women in the Ministry Part 3: The Speaking of Women and the Prohibition of the Law, Bibliotheca Sacra (145.315), (1988)

- ^ House, A Biblical View of Women in the Ministry Part 3: The Speaking of Women and the Prohibition of the Law, Bibliotheca Sacra (145.315), (1988)

- ^ Moss, NIV Commentary: 1, 2 Timothy & Titus, p. 60 (1994)

- ^ Perriman, "What Eve Did, What Women Shouldn't Do: The Meaning of Authenteo in 1 Timothy 2:12" Archived 2010-11-05 at the Wayback Machine, Tyndale Bulletin (44.1.137), (1993)

- ^ Köstenberger, Schreiner, and Baldwin, eds. (complementarians), Women in the Church: A Fresh Analysis of 1 Timothy 2:9–15 (1995)

- ^ a b Köstenberger, Women in the Church: An Analysis and Application of 1 Timothy 2:9–15 (1995)

- ^ Wolters, "A Semantic Study of and its Derivatives", Journal for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (11.1.54), (2006); originally published in Journal of Greco-Roman Christianity and Judaism (1.145–175), (2000)

- ^ a b Köstenbereger, "Teaching and Usurping Authority: I Timothy 2:11–15" (Ch 12) by Linda L. Belleville, Journal for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (10.1.44), 2005

- ^ the Scholia (fifth to first century B.C.) to Aeschylus's tragedy Eumenides

- ^ Aristonicus (first century B.C.

- ^ "To respond to the specific criticisms lodged by Belleville one at a time, (1) her argument that infinitives are not verbs is hardly borne out by a look at the standard grammars. Wallace's extensive treatment is representative. Under the overall rubric of 'verb', he treats infinitives as verbal nouns that exemplify some of the characteristics of the verb and some of the noun. Hence, Belleville's proposal that infinitives are nouns, not verbs, is unduly dichotomistic and fails to do justice to the verbal characteristics commonly understood to reside in infinitives". Köstenbereger, "Teaching and Usurping Authority: I Timothy 2:11–15" (Ch 12) by Linda L. Belleville", Journal for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (10.1.43), 2005

- ^ 1 Timothy 4:11

- ^ 1 Timothy 6:2

- ^ 2 Timothy 2:2

- ^ a b c d Belleville, Linda L. "Teaching and Usurping Authority: I Timothy 2:11–15" (Ch 12), Journal for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (10.1.47), (1995)

- ^ Belleville, Linda L. "Teaching and Usurping Authority: I Timothy 2:11–15" (Ch 12), Journal for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (10.1.49), (1995)

- ^ Wilshire, L. E. (2010). Insight into Two Biblical Passages. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America.

- ^ Wilshire, L. E. (2010). (p.29).

- ^ Wilshire, L. E. (2010), p.28.

- ^ Pearson, B.A. (2006). "Gnosticism, Judaism, and Egyptian Christianity". Minneapolis, MN. Fortress Press

- ^ On the Posterity of Cain and his Exile, XV. 52

- ^ That the Worse is Wont to Attack the Better, XIV. 48 & XXI. 78

- ^ Efird, J.M. (1990). "A Grammar for New Testament Greek". Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, pp. 5 & 9.

- ^ Pearson, pp. 103-105

- ^ John Dickson, Hearing Her Voice: A Case for Women Giving Sermons. Zondervan, 2014.