Belgian colonial empire

Belgian colonial empire | |

|---|---|

Map of Belgium's colonies at their maximum extent. | |

| Capital | Brussels |

| Common languages | French served as the main colonial language, but Dutch was also used to a lesser extent Local:

various |

| Government | Constitutional monarchy |

| History | |

| 15 November 1908 | |

| 1 July 1962 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,430,270 km2 (938,330 sq mi) |

Belgium controlled several territories and concessions during the colonial era, principally the Belgian Congo (modern DRC) from 1908 to 1960 and Ruanda-Urundi (modern Rwanda and Burundi) from 1922 to 1962. It also had small concessions in Guatemala (1843–1854) and in China (1902–1931) and was a co-administrator of the Tangier International Zone in Morocco.

Roughly 98% of Belgium's overseas territory was just one colony (about 76 times larger than Belgium itself) – known as the Belgian Congo. The colony was founded in 1908 following the transfer of sovereignty from the Congo Free State, which was the personal property of Belgium's king, Leopold II. The violence used by Free State officials against indigenous Congolese and the ruthless system of economic extraction had led to intense diplomatic pressure on Belgium to take official control of the country. Belgian rule in the Congo was based on the "colonial trinity" (trinité coloniale) of state, missionary and private company interests. During the 1940s and 1950s, the Congo experienced extensive urbanization and the administration aimed to make it into a "model colony." As the result of a widespread and increasingly radical pro-independence movement, the Congo achieved independence, as the Republic of Congo-Léopoldville in 1960.

Of Belgium's other colonies, the most significant was Ruanda-Urundi, a portion of German East Africa, which was given to Belgium as a League of Nations Mandate, when Germany lost all of its colonies at the end of World War I. Following the Rwandan Revolution, the mandate became the independent states of Burundi and Rwanda in 1962.[1]

Background in the early 19th century

Belgium, a constitutional monarchy, gained its independence in 1830 from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. By the time this was universally recognized in 1839, most European powers already had colonies and protectorates outside Europe and had begun to form spheres of influence.

During the 1840s and 50s, King Leopold I tentatively supported several proposals to acquire territories overseas. In 1843, he signed a contract with Ladd & Co. to colonize the Kingdom of Hawaii, but the deal fell apart when Ladd & Co. ran into financial difficulties.[2] Belgian traders also extended their influence in West Africa but this too fell apart following the Rio Nuñez Incident of 1849 and growing Anglo-French rivalry in the region.

By the time Belgium's second king, Leopold II, was crowned, Belgian enthusiasm for colonialism had abated. Successive governments viewed colonial expansion as economically and politically risky and fundamentally unrewarding, and believed that informal empire, continuing Belgium's booming industrial trade in South America and Russia, was much more promising. As a result, Leopold pursued his colonial ambitions without the support of the Belgian government. The archives of the Belgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade show that Leopold investigated possible colonies in dozens of territories.[3]

The Congo

Congo Free State (1885–1908)

Colonization of the Congo began in the late 19th century. King Leopold II of Belgium, frustrated by his nation's lack of international power and prestige, tried to persuade the Belgian government to support colonial expansion around the then-largely unexplored Congo Basin. Their refusal led Leopold to create a state under his own personal rule. With support from a number of Western countries who saw Leopold as a useful buffer between rival colonial powers, Leopold achieved international recognition for the Congo Free State in 1885.[4]

The Free State government exploited the Congo for its natural resources, first ivory and later rubber which was becoming a valuable commodity. With the support of the Free State's military, the Force Publique, the territory was divided into private concessions. The Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company (ABIR), among others, used force and brutality to extract profit from the territory. Their regime in the Congo used forced labour, and murder and mutilation on indigenous Congolese who did not fulfill quotas for rubber collections. Millions of Congolese died during this time.[5] Many deaths can be attributed to new diseases introduced by contact with European colonists, including smallpox which killed nearly half the population in the areas surrounding the lower Congo River.[6]

A sharp reduction of the population of the Congo through excess deaths occurred in the Free State period but estimates of the deaths toll vary considerably. Although the figures are estimates, it is believed that as many as ten million Congolese died during the period,[7][8][9][10] roughly a fifth of the population. As the first census did not take place until 1924, it is difficult to quantify the population loss of the period and these figures have been disputed by some who, like William Rubinstein, claim that the figures cited by Adam Hochschild are speculative estimates based on little evidence.[11]

Although the Congo Free State was not a Belgian colony, Belgium was its chief beneficiary in terms of trade and the employment of its citizens. Leopold II personally accumulated considerable wealth from exports of rubber and ivory acquired at gunpoint. Much of this was spent on public buildings in Brussels, Ostend and Antwerp.

Belgian Congo (1908–1960)

Leopold achieved international recognition for the Congo Free State in 1885.[4] By the turn of the century, however, the violence used by Free State officials against indigenous Congolese and the ruthless system of economic extraction led to intense diplomatic pressure on Belgium to take official control of the country, which it did in 1908, creating the Belgian Congo.[12]

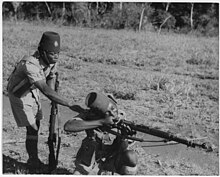

Belgian rule in the Congo was based on the "colonial trinity" (trinité coloniale) of state, missionary and private company interests.[13] The privileging of Belgian commercial interests meant that large amounts of capital flowed into the Congo and that individual regions became specialised. On many occasions, the interests of the government and private enterprise became closely tied, and the state helped companies break strikes and remove other barriers raised by the indigenous population.[13] The country was split into nesting, hierarchically organised administrative subdivisions, and run uniformly according to a set "native policy" (politique indigène). This was in contrast to the British and the French, who generally favoured the system of indirect rule whereby traditional leaders were retained in positions of authority under colonial oversight. During World War I, Congolese troops participated in offensives against German forces in the area of modern-day Rwanda and Burundi which were placed under Belgian occupation. The Congo had a high degree of racial segregation. The large numbers of white immigrants who moved to the Congo after the end of World War II came from across the social spectrum, but were always treated as superior to blacks.[14]

Congolese troops participated in World War II and were instrumental in forcing the Italians out of their East African colonies during the East African Campaign. During the 1940s and 1950s, the Congo had extensive urbanization, and the colonial administration began various development programmes aimed at making the territory into a "model colony".[15] One of the results was the development of a new middle class of Europeanised African "évolués" in the cities.[15] By the 1950s the Congo had a wage labour force twice as large as that in any other African colony.[16]

In 1960, as the result of a widespread and increasingly radical pro-independence movement, the Congo achieved independence, becoming the Republic of Congo-Léopoldville under Patrice Lumumba and Joseph Kasa-Vubu. Poor relations between factions within the Congo, the continued involvement of Belgium in Congolese affairs, and intervention by major parties of the Cold War led to a five-year-long period of war and political instability, known as the Congo Crisis, from 1960 to 1965. This ended with the seizure of power by Joseph-Désiré Mobutu.

Ruanda-Urundi

Ruanda-Urundi was a part of German East Africa under Belgian military occupation from 1916 to 1924 in the aftermath of World War I, when a military expedition had removed the Germans from the colony. It became a League of Nations Class B mandate allotted to Belgium, from 1924 to 1945. It was designated as a United Nations trust territory, still under Belgian administration, until 1962, when it developed into the independent states of Rwanda and Burundi. After Belgium began administering the colony, it generally maintained the policies established by the Germans, including indirect rule via local Tutsi rulers, and a policy of ethnic identity cards (later retained in the Republic of Rwanda). Revolts and violence against Tutsi, known as the Rwandan Revolution, occurred in the events leading to independence.

Minor possessions

Santo Tomás, Guatemala (1843–1854)

In 1842, a ship sent by King Leopold I of Belgium arrived in Guatemala; the Belgians observed the natural riches of the department of Izabal and decided to settle in Santo Tomas de Castilla and build infrastructure in the region. Rafael Carrera gave them the region in exchange for sixteen thousand pesos every year from the government of Guatemala. On 4 May 1843, the Guatemalan parliament issued a decree giving the district of Santo Tomás "in perpetuity" to the Compagnie belge de colonisation, a private Belgian company under the protection of King Leopold I of Belgium. It replaced the failed British Eastern Coast of Central America Commercial and Agricultural Company.[17] Belgian colonizing efforts in Guatemala ceased in 1854, due to lack of financing and high mortality due to yellow fever and malaria, endemic diseases of the tropical climate.[18]

Status

While the Compagnie belge de colonisation was granted the land in perpetuity, the concession did not become a colony in the political sense. Article 4 of the May 1842 Acte de concession clearly stated that the cession of the territory to the Belgian company did not involve, implicitly or explicitly, a cession of sovereignty over the territory, which would forever remain under the sovereignty and jurisdiction of Guatemala. Article 5 stated that upon their arrival on the territory, the settlers would become Guatemalan natives (indigènes de Guatemala) fully subject to the existing constitution and laws of the country, relinquishing their former Belgian or other national birthright, as well as any claim to any privileges or immunity as foreigners. Justice was to be administered by judges named by the government (art. 40). No foreign troops were to be allowed on the concession and Guatemalan troops were to garrison two forts that were to be built near the projected new town. (art. 18–22) [19]

Tianjin Concession (1900–1931)

The city of Tianjin (Tientsin), a treaty port in China (1860–1945) included nine foreign-controlled concessions (Chinese: 租界; pinyin: zujie). In the years following the Boxer Rebellion, the diplomat Maurice Joostens negotiated a concession for Belgium. The Belgian concession was proclaimed on 7 November 1900 and spanned some 100 hectares (250 acres).[20] Although Belgian companies invested in Tianjin, especially in the city's tram system, the Belgian concession remained inactive. An agreement was reached between the Belgian and Chinese governments in August 1929 to return the concession to China.[21] The agreement was approved by the Belgian parliament on 13 July 1931.

In the late 19th century, Belgian engineers were employed on construction of the Beijing–Hankou Railway, leading the Belgian government to unsuccessfully claim a concession in Hankou (Hankow). The Belgian claim was never formally recognised and the proposal was dropped in 1908.[22]

Isola Comacina (1919)

In 1919, the island of Comacina was bequeathed to King Albert I of Belgium for a year, and became an enclave under the sovereignty of Belgium. After a year, it was returned to the Italian State in 1920. The Consul of Belgium and the president of the Brera Academy established a charitable foundation with the goal of building a village for artists and a hotel.[23]

See also

- History of Belgium

- Atrocities in the Congo Free State

- Foreign relations of Belgium

- Rio Nuñez incident

- Société Belge d'Études Coloniales (est. 1894)

- Colonial University of Belgium (est. 1920 in Antwerp)

- Institut Royal Colonial Belge (est. 1928)

- Belgium–Mexico relations

Notes and references

Footnotes

References

- ^ "Belgium's role in Rwandan genocide". Le Monde Diplomatique. 1 June 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ Ricord, John; Williams, Stephen H.; Marshall, James F. B. (1846). Report of the proceedings and evidence in the arbitration between the King and Government of the Hawaiian Islands and Ladd & Co., before Messrs. Stephen H. Williams & James F. B. Marshall, arbitrators under compact. C.E. Hitchcock, printer, Hawaiian Government press.

- ^ Ansiaux, Robert (December 2006). "Early Belgian Colonial Efforts: The Long and Fateful Shadow of Leopold I" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help). The archives contain files opened at Leopold's request on Algeria, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Paraguay, Mexico-State of Puebla, Sandwich Islands, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, San Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Rio Nunez, Marie (West coast of Africa), Bolivia, Colombia, Guiana, Argentina (La Plata), Argentina (Villaguay), Patagonia, Florida, Texas, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Missouri, Kansas, Isle of Pines, Cozumel, St. Bartholomew Island, Haiti, Tortugas, Faroe Islands, Portugal, Isle of Nordstrand, Cyprus, Surinam, India, Java, Philippines, Abyssinia, Barbary Coast, Guinea Coast, Madagascar, Republic of South Africa, Nicobar, Singapore, New Zealand, New Guinea (Papua), Australia, Fiji, Malaysia, Marianas Island, the New Hebrides, and Samoa. - ^ a b Pakenham 1992, pp. 253–5.

- ^ Religious Tolerance Organisation: The Congo Free State Genocide. Retrieved 14 May 2007.

- ^ John D. Fage, The Cambridge History of Africa: From the earliest times to c. 500 BC, Cambridge University Press, 1982, p. 748. ISBN 0-521-22803-4

- ^ Hochschild.

- ^ Ndaywel è Nziem, Isidore. Histoire générale du Congo: De l'héritage ancien à la République Démocratique.

- ^ "Congo Free State, 1885–1908". Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ^ "King Leopold's legacy of DR Congo violence". 24 February 2004. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Rubinstein, W. D. (2004). Genocide: a history. Pearson Education. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0-582-50601-8

- ^ Pakenham 1992, pp. 588–9.

- ^ a b Turner 2007, p. 28.

- ^ Turner 2007, p. 29.

- ^ a b Freund 1998, pp. 198–9.

- ^ Freund 1998, p. 198.

- ^ "New Physical, Political, Industrial and Commercial Map of Central America and the Antilles" Archived 24 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Library of Congress, World Digital Library, accessed 27 May 2013

- ^ "Santo Tomas de Castilla Archived 5 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Britannica Encyclopedia

- ^ Colonisation dans l'Amérique centrale du District de Santo-Tomas de Guatemala, Paris, 1843, p. 32–36.

- ^ Neild 2015, p. 248.

- ^ Neild 2015, pp. 248–9.

- ^ Neild 2015, p. 106.

- ^ Jacobs, Frank (15 May 2012). "Enclave-Hunting in Switzerland". New York Times. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

Bibliography

- Anstey, Roger (1966). King Leopold's Legacy: The Congo under Belgian Rule 1908–1960. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nzongola-Ntalaja, Georges (2002). The Congo From Leopold to Kabila: A People's History. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-052-8.

- Freund, Bill (1998). The Making of Contemporary Africa: The Development of African Society since 1800 (2nd ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-69872-3.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1992). The Scramble for Africa: the White Man's Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912 (13th ed.). London: Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-10449-2.

- Poddar, Prem, and Lars Jensen, eds., A historical companion to postcolonial literatures: Continental Europe and Its Empires (Edinburgh UP, 2008), "Belgium and its colonies" pp 6–57. excerpt

- Turner, Thomas (2007). The Congo Wars: Conflict, Myth, and Reality (2nd ed.). London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-688-9.

- Neild, Robert (2015). China's Foreign Places: The Foreign Presence in China in the Treaty Port Era, 1840–1943. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-988-8139-28-6.

External links

- Belgian Concession Archived 15 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine at "Tianjin under Nine Flags" Project (University of Bristol)

- Belgian colonial empire

- 1885 establishments in Belgium

- 1962 disestablishments in Belgium

- 1885 establishments in Africa

- 1962 disestablishments in Africa

- States and territories established in 1885

- States and territories disestablished in 1962

- Former Belgian colonies

- Germanic empires

- 20th century in Belgium

- History of European colonialism

- Overseas empires

- Historical transcontinental empires

- Belgium–Burundi relations

- Belgium–China relations

- Belgium–Democratic Republic of the Congo relations

- Belgium–Guatemala relations

- Belgium–Morocco relations

- Belgium–Rwanda relations

- Former empires