Burhanuddin Harahap

Burhanuddin Harahap | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, c. 1952 | |

| 9th Prime Minister of Indonesia | |

| In office 12 August 1955 – 24 March 1956 | |

| Preceded by | Ali Sastroamidjojo |

| Succeeded by | Ali Sastroamidjojo |

| 9th Minister of Defense | |

| In office 12 August 1955 – 24 March 1956 | |

| Preceded by | Hamengkubuwono IX |

| Succeeded by | Ali Sastroamidjojo |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 February 1917 Medan, Dutch East Indies |

| Died | 14 June 1987 (aged 70) Jakarta, Indonesia |

| Resting place | Tanah Kusir Cemetery |

| Political party | Masyumi (1945–1960) |

| Spouse |

Siti Bariyah (m. 1948) |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater | Gadjah Mada |

| Occupation |

|

Burhanuddin Harahap (EVO: Boerhanoeddin Harahap; 12 February 1917 – 14 June 1987) was an Indonesian politician and lawyer who served as the 9th prime minister of Indonesia from 1955 until 1956. A member of the Masyumi Party, he also served as Minister of Defense from 1955 until 1956. Born to a Batak family in North Sumatra, his father worked as a civil servant in the colonial government. Burhanuddin moved to Java to pursue higher education, becoming active in Islamic student organizations and enrolling in the Rechts Hogeschool in Batavia (now Jakarta) before his studies were interrupted by the Japanese invasion of the colony in 1942. During the Japanese occupation period, he served as public prosecutor in state courts in Jakarta and Yogyakarta. Following the proclamation of Indonesian independence, he became more involved in politics, joining the Masyumi Party and rising through its ranks to become a prominent party member, becoming the leader of Masyumi's parliamentary faction by 1950.

In 1953, Burhanuddin contributed to the collapse of Prime Minister Wilopo's cabinet and unsuccessfully attempted forming a new cabinet. After the downfall of Prime Minister Ali Sastroamidjojo's first cabinet, he was again given the chance to form a government. He formed a caretaker government with the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and several minor political parties. As prime minister, Burhanuddin reversed many of his predecessor's policies. He adopted a pragmatic economic policy, abolishing the pro-indigenous Benteng program, while seeking to remove the influence of the Indonesian National Party and Indonesian Communist Party from the military and government. Additionally, his government initiated some measures towards Acehnese autonomy and his government saw the dissolution of the Netherlands-Indonesian Union in 1956. The poor performance of the Masyumi in the 1955 election, however, weakened the cabinet's political position and alliance with NU. In the last weeks of his government, foreign negotiations over the Western New Guinea dispute broke down the coalition, with his tenure ending in March 1956.

Afterwards, political tensions forced him to flee to Sumatra in 1957, and he joined the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PRRI) rebellion upon its declaration in February 1958. Within PRRI, Burhanuddin was appointed ministers of defense and justice in the revolutionary government's declared cabinet. Following continued military setbacks of the movement, including the capture of the revolutionary government's capital of Padang, the movement's civilian leader's were no longer able to exercise any control over the movement as it retreated into the jungles and mountains. By 1961, most civilian leaders had realized that the movement was hopeless. In late August 1961, Burhanuddin surrendered to military authorities at Padangsidempuan. He was initially permitted to remain free, although in March 1962 he was arrested, along with the other PRRI civilian leaders and imprisoned during the transition to the New Order in 1966. Following his release, he largely left politics, although he took part in the 1980 Petition of Fifty document, which criticized President Suharto's use of Pancasila against political opponents, prior to his death in 1987.

Early life and career

Burhanuddin was born in Medan on 12 February 1917,[a] as the second children of Mohammad Yunus, a low-ranking official in a public prosecutor office, and his wife Siti Nurfiah.[1][4] Yunus was of South Tapanuli Batak descent,[5] and was often reassigned to other locations across North Sumatra.[1][4] Burhanuddin followed his father's reassignments, and he went to a Hollandsch-Inlandsche School in Bagansiapiapi.[6] After graduating, he continued his education at a Meer Uitgebreid Lager Onderwijs in Padang,[7] then an Algemene Middelbare School in Yogyakarta, from which he graduated in 1938. He continued his education at the Rechts Hogeschool (Batavia Law Institute), but his studies were interrupted by the Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies in 1942.[2] He later resumed his law degree at Gadjah Mada University, completing it in 1951.[8] During his time in Yogyakarta, Burhanuddin joined the Jong Islamieten Bond in 1936, becoming its activist and local chair. When he moved to Batavia, he became the secretary of the Studenten Islam Studie-Club, an organization which had split off from the Bond in 1934. He also became a member of the Indonesian Students' Association.[2][9] Along with Jusuf Wibisono and Mohammad Roem, Burhanuddin organized the publication of the Dutch-language journal Moslim Reveil espousing Indonesian Islamic nationalism.[10]

Early political career

Between 1942 and 1948, Burhanuddin served as public prosecutor in the Jakarta State Court and later the Yogyakarta State Court.[2] When the Masyumi Islamic party was formed in November 1945, Burhanuddin became a member, although he did not initially hold any leadership position. Due to internal disputes within Masyumi, however, Burhanuddin became more involved and quickly went up the party ranks, being elected to a leadership position by 1949. He was also appointed by Sutan Sjahrir to the Working Body of the Central Indonesian National Committee in 1946.[11] Burhanuddin, along with fellow Masyumi politician Kasman Singodimedjo, also lobbied the Indonesian Army in 1948 in favor of the Darul Islam movement and its founding of Islamist militia units during the Indonesian National Revolution.[12] By 1950, Burhanuddin had become the leader of Masyumi's parliamentary faction in the Provisional People's Representative Council.[11] During the prime ministership of Mohammad Natsir (a Masyumi member), Burhanuddin found himself within the wing of the Masyumi Party which had significant disagreements with the prime minister, and he abstained in the parliamentary vote of confidence against Natsir in October 1950.[13] In 1952, Burhanuddin became a member of the Masyumi Party's Executive Committee.[9]

Burhanuddin was also initially appointed as Masyumi's representative to the Central Electoral Committee in April 1953 during the premiership of Wilopo, but disputes with the Indonesian National Party (PNI) over the committee composition caused it to fail to convene.[14] Burhanuddin also contributed to the collapse of the cabinet later that year, when he threatened to withdraw Masyumi support for the government over a successful motion to establish formal diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union.[15] After the collapse of Wilopo's cabinet, two initial attempts at forming a new government by PNI and Masyumi failed, and after a series of negotiations between the two parties Burhanuddin was appointed formateur by President Sukarno on 8 July 1953. While Burhanuddin was acceptable to the PNI, and he was willing to make some concessions regarding policy and ministerial posts, PNI rejected Burhanuddin's offer due to his selection of Indonesian Socialist Party (PSI) member Sumitro Djojohadikusumo as Finance Minister and PNI's desire for the prime ministership itself. Burhanuddin attempted to form a cabinet without PNI by including the Christian and Catholic Parties, but the two parties refused to participate in a government which excluded PNI. After this failure, Burhanuddin returned his mandate to Sukarno on 18 July,[16] prior to the deadline given to him by Sukarno.[17] His succeeding formateur, Wongsonegoro of the Great Indonesia Unity Party, managed to organize the First Ali Sastroamidjojo Cabinet which excluded Masyumi from ministerial posts.[18]

Prime Minister: 1955–1956

Cabinet formation

Ali Sastroamidjojo's first cabinet collapsed in July 1955 due to tensions with the army, particularly caused by new appointments to the army high command following the resignation of chief of staff Bambang Soegeng.[19] Vice President Mohammad Hatta first appointed Sukiman (Masyumi), Wilopo (PNI) and Assaat as cabinet formateurs, but they failed as their proposed Hatta-led cabinet would result in Hatta no longer becoming vice-president – unacceptable to Masyumi.[20] Burhanuddin, who was a relative of acting army chief of staff Zulkifli Lubis, was then appointed as new formateur. After negotiations, Burhanuddin managed to secure a major concession from PNI – a willingness to accept a Masyumi prime minister – but could not reach a deal on appointed ministers. While Burhanuddin and PNI had agreed on which positions would be occupied by PNI ministers, Burhanuddin would not accept PNI's candidates, and vice versa with PNI on Burhanuddin's appointments. Burhanuddin then turned to the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and a number of minor political parties,[b] and his cabinet was sworn in on 12 August 1955 – Burhanuddin serving as both prime minister and defence minister.[21] His cabinet had 23 ministers – more than all previous cabinets.[22] Most of the ministers in the cabinet – with the exception of finance minister Sumitro and agriculture minister Mohammad Sardjan – also had no previous cabinet experience.[23]

Policy

It was intended that the cabinet would return its mandate after the upcoming elections had concluded, effectively making it a caretaker government and limiting its ability to influence long-term policy.[24] Burhanuddin's cabinet also suffered from a divergence of objectives of its constituent parties. While Masyumi (and PSI) aimed at reducing the political influence of the PNI and the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) within the government bureaucracy, many of the small political parties simply aimed to gain as much political clout as possible before their potential removal from parliament in upcoming 1955 elections.[22] Regardless, the cabinet reversed many of its predecessor's policies,[22] excluding nearly all ministers who had served in Ali's cabinet from its ranks.[25] In addition to changes in the bureaucratic structure and personnel, Burhanuddin also called for another general amnesty for members of the Darul Islam rebellion in West Java. This was in opposition to Ali, who preferred the use of force.[26][c] Working with the military, the cabinet also arrested and charged with corruption a number of high ranking officials from the previous government, including former economic affairs minister Iskaq Tjokrohadisurjo and former justice minister Djody Gondokusumo.[28] Despite NU and PSII also being Islamist parties, they had a significantly different support base to Masyumi,[d] and resisted many of the proposed changes to the bureaucratic and economic structures of the country.[29]

The Burhanuddin cabinet successfully passed a draft electoral law which would regulate the 1955 election.[30] In the weeks leading up to the 1955 election, the cabinet also made several populist policies, including reducing petrol prices by nearly half and simplifying import regulations.[31] While several members of the cabinet had argued for delaying elections, it was decided that the election would be mostly held on schedule, on 29 September 1955.[32] Although initially many expected that Masyumi would come in first,[33] the election produced a weak result for Masyumi with PNI instead winning the most seats while NU's position in the parliament was strengthened. This complicated the coalition between the two especially with Masyumi's minor party allies being wiped out of parliament and the PSI losing most of its seats.[34] While Burhanuddin's coalition still held a narrow majority in parliament, NU and PSII now held much more sway. As a result of the shifting balance of political power, Masyumi opted to back out from supporting an anticorruption bill in parliament, which could have antagonized the NU and had received a presidential veto.[35][36] Under NU pressure, Burhanuddin also agreed to appoint Abdul Haris Nasution – who had previously lost his post due to the 17 October affair in 1952 – back to his old position as army chief of staff.[37] Prior to this, Burhanuddin already liked Nasution personally – they were both of South Tapanuli descent – and had offered him a post in his cabinet.[5]

Even with the changed political situation, Burhanuddin's cabinet continued to remove PNI and PKI-supporting personnel from civilian and military offices alike – at the cost of reduced performance of the ministries.[38] An incident in December 1955 where Burhanuddin attempted to appoint an officer, Sujono, to Indonesian Air Force high command resulted in the resignation of its chief of staff Soerjadi Soerjadarma. During the intended swearing-in, a number of air force NCOs stormed the ceremony (attended by a number of foreign dignitaries and military attaches) to beat up Sujono and several officers supporting him, and they also stole the air force's standard. After the incident, Burhanuddin ordered the house arrest of Soerjadarma. This brought the cabinet into political conflict with Sukarno which it lost – the appointment was reversed and the resignation was not accepted.[39]

Economic and foreign policy

Economically, Burhanuddin's cabinet engaged in rationalization efforts, reversing the policies of PNI in favor of a pragmatic approach which welcomed foreign and private capital into Indonesia. Additionally, in order to curb the high inflation which was in place during 1955, the cabinet opted to liberalize imports which had been largely restricted to curb deficits by prior administrations. These policies resulted in the stabilization of prices, although imports did increase significantly.[40][41] Due to floods in 1955, however, the cabinet could not control the price of rice which rose sharply before normalizing in the cabinet's last weeks.[42] Burhanuddin's cabinet also abolished the pro-indigenous Benteng program and unilaterally abrogated the Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference – specifically, Indonesia's remaining debt obligations exceeding 3 billion guilders.[43] Burhanuddin also initiated some measures towards Acehnese autonomy – which was followed on by the succeeding cabinet by granting Aceh autonomous province status.[44]

In foreign policy, the Burhanuddin cabinet aimed to placate the concerns of the United States with regards to Indonesia's relations with the communist bloc in order to gain American support in the Western New Guinea dispute.[45] The US was generally supportive of Masyumi (due to their opposition to communists), and had responded positively to Burhanuddin's appointment.[46] With the efforts of foreign minister Mohammad Roem and the government, Indonesia managed to secure a commitment from Australia to not support the Dutch, and managed to bring up the issue in the United Nations General Assembly.[47] It also attempted to engage in negotiations with the Netherlands over the issue, releasing a number of Dutch prisoners as a sign of goodwill. Prior to the election, however, it had limited ability to make concessions, due to the politically charged nature of the issue.[48] After the election, despite opposition from Sukarno and PNI, Burhanuddin continued with negotiations,[49] which resulted in the withdrawal of NU and PSII ministers from the government in late January 1956. Due to this withdrawal, the Burhanuddin government lacked the majority needed in parliament to ratify any agreements made.[50][51] The talks proceeded to break down, with the Indonesian government announcing its unilateral withdrawal from the Netherlands-Indonesia Union on 12 February 1956.[52]

With the cabinet set to dissolve in March 1956 – one month earlier than previously scheduled – personnel changes and grants of government loans were intensified throughout February, with a walkout of opposition parties including speaker of parliament Sartono on 28 February. Burhanuddin returned his mandate to Sukarno on 3 March 1956, and for the next three weeks it served as a demissionary cabinet.[53][54] The Second Ali Sastroamidjojo Cabinet succeeded it, and included both Masyumi and NU within the cabinet,[55] but excluded most former ministers of the Burhanuddin government including Burhanuddin himself.[56] Increased tensions between the coalition parties resulted in Masyumi's withdrawal from the cabinet in January 1957, and in the ensuing two months of political crisis, Burhanuddin offered a proposal whereas Sukarno would play a more important role in day-to-day politics and attend cabinet meetings. This proposal did not pass, however, and the Ali cabinet collapsed in March 1957.[57]

PRRI rebellion

In late 1957, the political situation in Indonesia rapidly grew unfavorable – the failure of the United Nations General Assembly to take up the Western New Guinea dispute had resulted in Sukarno forcefully nationalizing Dutch companies and property, and an unsuccessful assassination attempt was made on Sukarno, killing many children.[58][59] Burhanuddin and other Masyumi leaders were especially in the spotlight, due to his cabinet's economic policy which was perceived to have benefited foreign importers and Chinese Indonesians.[60] Burhanuddin, along with other Masyumi leaders such as Natsir and Sjafruddin Prawiranegara, were investigated for the assassination attempt. Indonesian newspapers began to attack the three figures, and rumors spread that they had been killed or arrested – some of Burhanuddin's family members travelled from Sumatra to Jakarta, believing that he had died.[58][59] In early December 1957, Burhanuddin opted to flee Jakarta when he heard that he would be arrested. Within the following month, the other leaders followed him.[58][61]

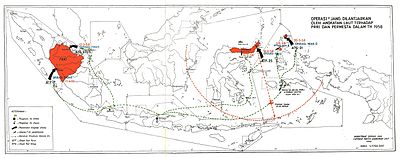

Under the auspices of visiting a friend, Burhanuddin was in Padang in mid-January 1958, and along with other Masyumi leaders he attended a conference at the town of Sungai Dareh with dissident military officers.[62] In later accounts, Burhanuddin claimed that the military officers were advocating Sumatran secession from Indonesia, which he and other civilian leaders opposed.[63][64] In the following weeks, with Sukarno abroad, the government in Jakarta under prime minister Djuanda Kartawidjaja attempted to negotiate a peaceful resolution to the conflict, with Masyumi members who had not fled to Sumatra – such as Roem – attempting to persuade Natsir, Sjafruddin and Burhanuddin not to form a subversive government.[65][66] On 10 February 1958, the dissident military officers under Ahmad Husein issued an ultimatum to the central government – the dissolution of the Djuanda Cabinet and the formation of a new cabinet by vice president Hatta and defence minister Hamengkubuwono IX.[66][67] When the central government rejected the ultimatum, the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PRRI) was declared on 15 February 1958 in Padang. Burhanuddin was appointed as ministers of defence and justice in the government's declared cabinet.[66][67] Burhanuddin later claimed that he was not fully in favor of forming a rival government, that he had only agreed to be appointed minister of home affairs simply so there could be a cabinet, and that the military officers had reassigned him without consultation.[68][69]

The rebellion soon faced major military defeats against the Indonesian government, which had captured the major rebel-held cities of Padang, Medan and Pekanbaru by May 1958 while facing comparatively little armed resistance. This also brought down any possibility of a foreign intervention – namely of the United States which had unrealized hopes for a general uprising against Sukarno.[70][71] PRRI soon was forced into guerilla warfare, with Burhanuddin being attached to Dahlan Djambek's northern sector based in Agam Regency.[72] Due to continued government military pressure, however, they were soon dislodged from their bases there and into the jungles and mountains of Sumatra, with the final major PRRI stronghold of Koto Tinggi being taken in July 1960. After the loss of their base, PRRI's civilian leaders could no longer exercise any control over the movement.[73]

By 1961, army chief of staff Abdul Haris Nasution was negotiating with the rebel army officers, offering general amnesty. With Husein surrendering his forces on 21 June, most of the civilian leaders realized that the movement was hopeless. On 17 August 1961, Sukarno offered another general amnesty for any PRRI members who surrendered before 5 October 1961. Along with Sjafruddin and Assaat, Burhanuddin first called for PRRI forces to cease hostilities against the Indonesian government, before surrendering to military authorities at Padangsidempuan in late August 1961.[74][75] PRRI's leadership was now reduced to just Natsir and Djambek, and with the death of the latter in September, Natsir surrendered too, ending the rebellion.[76] Burhanuddin was initially brought to Medan after Natsir's surrender, and was initially permitted to remain free. However, he was arrested along with the other PRRI civilian leaders in March 1962 and brought to Jakarta, before being separated from the others and incarcerated in Pati Regency for two years. He was brought back to Jakarta for continued imprisonment in 1964. He would be released following the fall of Sukarno, being let out along with other Masyumi leaders in July 1966.[77]

Later life and death

After his release, there were attempts by former Masyumi leaders to reform the party – and Burhanuddin along with the other leaders attended a meeting of Parmusi in August 1968. However, it soon became clear that Suharto would not accept a Parmusi under Masyumi leadership, rejecting the party's leadership as elected by members in a November 1968 congress.[78] Burhanuddin himself did not show much interest in obtaining a party leadership position, instead turning to other fields. He lobbied for the restoration of the Abadi daily newspaper, and later became its chief editor between 1968 and 1974. He was also active in the Indonesian Dakwah Council.[79][80] In 1980, Suharto gave a speech decrying communism and religion as "discredited philosophies", and promoted Pancasila in their place. This caused a backlash from both Muslim groups and the armed forces, and many retired figures including Burhanuddin came together to sign the "Petition of Fifty" on 13 May 1980. The petition condemned Suharto's use of Pancasila as a political weapon against opposition.[81]

He died in Jakarta's Harapan Kita Cardiac Hospital on 14 June 1987, after having suffered from heart problems since 1976. He was buried in the Tanah Kusir Cemetery.[3][82]

Personal life and family

Burhanuddin was described as a fan of tennis and sambal, the former since his time as a student in Yogyakarta.[80][83] He married Siti Bariyah, the daughter of a local official in Yogyakarta.[84][85] The couple is known to have a son and a daughter, and no grandchildren at the time of Burhanuddin's death.[85]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ His biographies state 12 February,[1][2] while his gravestone states 12 March.[3]

- ^ These parties include the PSI, Christian Party, Catholic Party, PSII, PRN, Labour, PIR, and Parindra.[21]

- ^ Burhanuddin and Lubis had been negotiating with the Darul Islam leader Kartosuwiryo since at least 1952.[27]

- ^ NU and PSII derived most of their voter base from Javanese Muslims, while Masyumi mostly received support from the Sundanese and from outside Java.[29]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Busyairi 1989, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d Kami perkenalkan (in Indonesian). Ministry of Information of Indonesia. 1952. p. 94. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Menjelajahi Rumah Terakhir 10 Mantan Perdana Menteri". detiknews (in Indonesian). 16 August 2006. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ a b Fogg 2019, p. 173.

- ^ a b Kahin 2012, p. 126.

- ^ Busyairi 1989, p. 8.

- ^ Busyairi 1989, p. 9.

- ^ Busyairi 1989, p. 14.

- ^ a b Madinier 2015, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Ardanareswari, Indira. "Pemilu Pertama Indonesia Terlaksana Berkat Burhanuddin Harahap". tirto.id (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 12 March 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ a b Fogg 2019, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Fogg 2019, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Feith 2006, p. 152.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 291–292.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 331–336.

- ^ Karma 1987, p. 16.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 336–339.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 398–402.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 416–417.

- ^ a b Feith 2006, pp. 417–419.

- ^ a b c Lucius 2003, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Thuỷ 2019, p. 126.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 421–422.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 420–421.

- ^ Formichi 2012, p. 163.

- ^ Madinier 2015, p. 174.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 422–423.

- ^ a b Lucius 2003, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Kahin 2012, p. 85.

- ^ Feith 2006, p. 426.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 424–425.

- ^ Kahin 1999, p. 177.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 434–436.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 437–439.

- ^ Lucius 2003, p. 136.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 442–443.

- ^ Feith 2006, p. 446.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 447–448.

- ^ Thuỷ 2019, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Feith 2006, p. 563.

- ^ Feith 2006, p. 461.

- ^ Thuỷ 2019, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Madinier 2015, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Lucius 2003, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Lucius 2003, p. 148.

- ^ Madinier 2015, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Penders 2021, p. 251.

- ^ Penders 2021, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Madinier 2015, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Penders 2021, p. 256.

- ^ Feith 2006, p. 455.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 456–459.

- ^ Busyairi 1989, p. 186.

- ^ Kahin 2012, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Feith 2006, p. 467.

- ^ Madinier 2015, pp. 232–237.

- ^ a b c Kahin 1999, pp. 204–205.

- ^ a b Madinier 2015, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Madinier 2015, p. 225.

- ^ Madinier 2015, p. 249.

- ^ Madinier 2015, p. 250.

- ^ Busyairi 1989, p. 145.

- ^ Madinier 2015, p. 251.

- ^ Kahin 1999, p. 208.

- ^ a b c Madinier 2015, p. 252.

- ^ a b Kahin 1999, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Busyairi 1989, p. 153.

- ^ Madinier 2015, p. 253.

- ^ Kahin 1999, pp. 214–216.

- ^ Madinier 2015, p. 257.

- ^ Kahin 1999, p. 218.

- ^ Kahin 1999, p. 225.

- ^ Madinier 2015, p. 260.

- ^ Kahin 1999, p. 226.

- ^ Kahin 1999, p. 227.

- ^ "0rde Lama, Syahrir, Natsir, Hamka:Penjara Tanpa Proses Hukum". Republika (in Indonesian). 19 January 2019. Archived from the original on 14 November 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Ward 2010, pp. 62–68.

- ^ Ward 2010, p. 64.

- ^ a b Karma 1987, p. 17.

- ^ Kahin 2012, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Karma 1987, pp. 13, 19.

- ^ Busyairi 1989, p. 11.

- ^ Busyairi 1989, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b Karma 1987, p. 18.

Sources

- Busyairi, Badruzzaman (1989). Boerhanoeddin Harahap: pilar demokrasi (in Indonesian). Bulan Bintang. ISBN 978-979-418-207-9. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Feith, Herbert (2006). The Decline of Constitutional Democracy in Indonesia. Equinox Publishing. ISBN 978-979-3780-45-0. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Fogg, Kevin W. (2019). Indonesia's Islamic Revolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-48787-0. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Formichi, Chiara (2012). Islam and the Making of the Nation: Kartosuwiryo and Political Islam in 20th Century Indonesia. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-26046-7. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Kahin, Audrey (1999). Rebellion to Integration: West Sumatra and the Indonesian Polity, 1926–1998. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-395-3. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Kahin, Audrey (2012). Islam, Nationalism and Democracy: a Political Biography of Mohammad Natsir. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-571-2. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Karma, D. S. (1987). "Perdana Menteri Tanpa Dasi". Melihat Pembentukan Dewan Dakwah Islam Indonesia (DDDI) dan Kontribusinya (in Indonesian). Tempo Publishing. ISBN 978-623-339-495-6. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Lucius, Robert E. (2003). A House Divided: The Decline and Fall of Masyumi (1950–1956) (PDF) (Thesis). Naval Postgraduate School. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Madinier, Remy (2015). Islam and Politics in Indonesia: The Masyumi Party between Democracy and Integralism. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-843-0. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Penders, C. L. M. (2021). The West New Guinea Debacle: Dutch Decolonisation and Indonesia, 1945–1962. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-48723-9. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Thuỷ, Phạm Văn (2019). Beyond Political Skin: Colonial to National Economies in Indonesia and Vietnam (1910s–1960s). Springer. ISBN 978-981-13-3711-6. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Ward, Ken (2010). The Foundation of the Partai Muslimin Indonesia. Equinox Publishing. ISBN 978-602-8397-01-8. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.