Chief Wahoo

Chief Wahoo was a logo used by the Cleveland Indians (now the Cleveland Guardians), a Major League Baseball (MLB) franchise based in Cleveland, Ohio, from 1951 to 2018.

As part of the larger Native American mascot controversy, the logo drew criticism from Native Americans, social scientists, and religious and educational groups, but was popular among fans of the team. During the 2010s, it was gradually replaced by a block "C", which became the primary logo in 2013. Chief Wahoo was officially retired following the 2018 season,[2][3][4] with it also barred from future National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum plaques and merchandise sold outside of Ohio.[5][6][3]

History

[edit]In 1932, the front page of the Cleveland Plain Dealer featured a cartoon by Fred George Reinert that used a caricatured Native American character with a definite resemblance to the later Chief Wahoo as a stand-in for the Cleveland Indians winning an important victory. The character came to be called "The Little Indian", eventually becoming a fixture in the paper's coverage of the team, including a small front-page visual box where his head would peek out to announce the outcome of the latest game. Journalist George Condon would write in 1972, "When the baseball club decided to adopt an Indian caricature as its official symbol, it hired an artist to draw a little guy who came very close to Reinert's creation; a blood brother, unquestionably."[7]

In 1947, Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck hired the J.F. Novak Company, designers of patches worn by the Cleveland police and fire departments, to create a new logo for his team. Seventeen-year-old draftsman Walter Goldbach, an employee of the Novak Company, was asked to perform the job.[8][9] Tasked with creating a mascot that "would convey a spirit of pure joy and unbridled enthusiasm", he created a smiling face with yellow skin and a prominent nose.[9] Goldbach has said that he had difficulty "figuring out how to make an Indian look like a cartoon",[9][10] and that he was probably influenced by the cartoon style that was popular at the time.[11]

How the name "Chief Wahoo" came to be used to refer to the Indians' mascot is less clear. The phrase had already been used for years before its use as a reference to the logo; the popular newspaper comic strip Big Chief Wahoo ran from 1936 to 1947.[7] One questionable origin myth indicates that the names "Indians" and "Chief Wahoo" were meant to honor Louis Sockalexis, an outfielder for the Indians' predecessors, the Cleveland Spiders, and one of the first Native Americans to play in Major League Baseball.[12] The Penobscot, Sockalexis' tribe, petitioned the Cleveland Indians to discontinue the use of Chief Wahoo.[13]

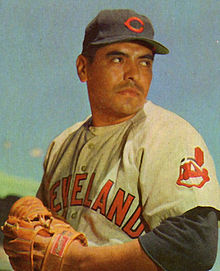

Another Native American baseball player, Allie Reynolds, pitched for the Indians for five years beginning in 1942, mostly as a starter. He was later traded to the New York Yankees. On October 6, 1950, the Plain Dealer, under the title of "Chief Wahoo Whizzing", stated "Allie (Chief Wahoo) Reynolds, the copper-skinned Creek," lost to Philadelphia, but "in the clutches, though, the Chief was a standup gent—tougher than Sitting Bull."[7] In subsequent articles, Reynolds was again called "Chief Wahoo", "old Wahoo", and just plain "Wahoo".[7]

In 1952, "Chief Wahoo" was given as the name for the Indians' physical mascot for the first time when a person in a Wahoo costume showed up for a children's party at Public Hall given by "Cleveland's dentists".[7] Sportswriters eventually took to calling the unnamed character "Chief Wahoo".[9] Goldbach has said that the logo's moniker is inaccurate.[10] Quoting a child he met while talking at a school, Goldbach explained in a 2008 interview, "He's not a chief, he's a brave. He only has one feather. Chiefs have full headdresses."[10]

In 1951, the mascot was redesigned with a smaller nose and red skin instead of yellow skin.[9] This would be the most long-lived version of the logo, with only minor changes; when it was first introduced, it had black outlines before being changed to have blue outlines in 1979.[8] After its introduction, the face of the 1951 logo was incorporated into other full-body depictions of the character.

Ohio sportswriter Terry Pluto has described comics of Chief Wahoo that would run on the front page of the Cleveland Plain Dealer in the 1950s, with the character's depiction signifying the outcome of a game. Wins were illustrated by Chief Wahoo holding a lantern in one hand and extending the index finger on his other. Losses were illustrated by a "battered" Chief Wahoo, complete with black eye, missing teeth and crumpled feathers.[14]

The Chief Wahoo logo was last worn by the Indians in a loss to the Houston Astros in the ALDS on October 8, 2018. News outlets noted the irony of the logo's final appearance being on Indigenous Peoples' Day/Columbus Day.[15][16][17]

Later variations

[edit]

By 1973, when the team was bought by Cleveland businessman Nick Mileti, they had introduced additional depictions of Chief Wahoo, some of which showed the character at bat. Mileti hired designer Leonard Benner to modify an existing at-bat design for use as a logo. Several changes were made: Wahoo's nose was made smaller, his body thinner, and he was now drawn as a right-handed batter instead of left-handed.[18] Overall, the design of Chief Wahoo remained largely similar to the previous version.[18] These modifications, however, heralded other changes to the team's use of Indian-themed imagery, such as the removal of a teepee from the outfield area.[18][19]

When Cleveland Municipal Stadium installed a new computer-programmed monocolor scoreboard in 1977, newspaper articles described how it could display animated depictions of Chief Wahoo yelling "Charge!"[20] By the 1978 season, home runs were celebrated with fireworks and a scoreboard animation of Chief Wahoo dancing.[21] The complete package of commissioned animations included an arrow skewering two players to signify a double-play.[20]

During his tenure as president of the team, Peter Bavasi asked players how the uniforms should look.[14] Bavasi has described Joe Carter and Pat Tabler suggesting that Chief Wahoo be added to the hats, with Tabler predicting that it would "sell like crazy".[14] Bavasi recalls expressing concern that it would offend Native American groups, but that player Bert Blyleven reassured him, "Nah, it shouldn't. Really looks like [manager] Phil Seghi."[14] Blyleven made a similar remark to Sports Illustrated, who described the resemblance as "uncanny".[22] Tabler's prediction was ultimately borne out, with hat sales increasing significantly after the reintroduction of Chief Wahoo.[23] The revised hat design has been described as a change "in keeping with Major League Baseball's trend toward 'old-style' simulacra."[24]

Around the time Bavasi added Chief Wahoo to the team's hats in 1986, he also banned "derogatory" banners at the stadium.[25] The elimination of references to Cleveland on the uniforms, including replacing the old style hats with Chief Wahoo, led to speculation that the team might be moved to another city ("Cleveland" was omitted on road jerseys from 1972 to 1977 and from 1983 to 1988; from 1978 to 1982, the city name was on the road grays, but the team often wore navy jerseys with the team name instead of the city name for many road games).[25][26]

Move to Jacobs Field

[edit]In 1994, the Indians moved from the Cleveland Municipal Stadium to Jacobs Field (later renamed Progressive Field). They considered replacing Chief Wahoo in 1993,[19][27] but it was ultimately retained.[28][29] Several years later, the Associated Press reported that the debate had not hurt the team's souvenir sales, which were better than those of any other team in the league at the time.[30]

From 1962 through 1994, a 28-foot (8.5 m)-tall, neon-lit sign of Chief Wahoo at bat stood above gate D of Cleveland Municipal Stadium. When the stadium was demolished, the neon sign was donated to the Western Reserve Historical Society.[31] Working with the original blueprints,[32] and the help of $50,000 in donations, the historical society refurbished the sign, which is now displayed in the group's museum.[31] Anonymous donors have since provided funds to support maintenance work that allows the sign to remain lit.[33]

According to a senior vice president and historian at the Western Reserve Historical Society,[34] the acquisition of a neon Chief Wahoo sign was debated for several reasons. Among them was the belief that it was "hugely negative for a portion of the population". Ultimately, the historical society decided that "history is history. This sign is a point in a major American issue, which is racial caricature. Some people have a problem with it, some people don't. It's important because it not only represents the rich history of baseball in Cleveland, it gets into a really deep issue in American history." The sign is displayed with written materials that show several points of view, including "The Legacy of Racism Continues", "Chief Wahoo: Brief History of a Civic Icon", and "Enthusiasm! That's Chief Wahoo!"[31]

Battle flag over USS Cleveland

[edit]

For several years, the USS Cleveland flew a battle flag featuring the Chief Wahoo logo. The time and circumstances under which the flag was first flown are not known, but the flag was retired in 2006 and presented to former Cleveland pitcher and World War II veteran Bob Feller. The flag had previously flown over center field at Cleveland Stadium.[35]

Use during spring training

[edit]

In 2009, the Cleveland Indians moved their spring training operations from their Grapefruit League home in Winter Haven, Florida to their new Cactus League home in Goodyear, Arizona. During the years the team trained in the Grapefruit League, a mural of Chief Wahoo was displayed on a nearby municipal water tower, which was touched up at least once in 1993.[36] However, because of the team's impending move, the city of Winter Haven did not bother to repaint the logo when it eventually faded.[37] Due to the expense of repainting the water tower, the logo remained there long after the team last trained in Florida; it was not until 2012 that it was finally replaced with Polk State College's Logo.[38][39]

Chief Wahoo creator Walter Goldbach and his wife spent 15 winters living in Winter Haven.[8] During the spring training season, Goldbach would work with the team when they conducted tours.[8] Goldbach later retired from his career as an artist, and medical issues prevented him from drawing in the last few years of his life.[8] He died in December 2017 at the age of 88.[40]

Merchandise and promotional tie-ins

[edit]An early piece of Chief Wahoo merchandise depicts a squatting Native American figure holding a stone tool in one hand and a scalp in the other.[41] Produced in 1949 by Rempel Manufacturing, Inc., of Akron, Ohio, the rubber Indian figure (marketed as "Big Chief Erie")[42] was based on an original sketch by Plain Dealer cartoonist Fred G. Reinert.

For its 100th anniversary, the team gave away blankets that depicted various incarnations of Chief Wahoo.[43] In 2011, the team gave away free T-shirts with a picture of a heart, a peace sign and Chief Wahoo.[44] The West Side Leader of Akron, Ohio declared this design "a lot better than the previous freebie shirt, which featured representations of three racing hot dogs".[44]

In 2005, the team partnered with a candy maker to produce a Chief Wahoo chocolate bar.[45] In 2013, the name "Wahoo Women" was used for a ladies' night out promotion,[46] and the team also ran a "Wahoo Wednesdays" promotion with Domino's Pizza.[47]

When Major League Baseball released a line of hats fashioned to resemble team mascots, a writer for Yahoo! Sports observed that the league had "wisely passed over fashioning Chief Wahoo into a polyester conversation piece".[48] Although Chief Wahoo was the logo for the Cleveland Indians, the official team mascot is a character named Slider. Major League Baseball does in fact sell a hat shaped to resemble Slider, who himself wears a Chief Wahoo hat.[49] The Cleveland Indians have also sold Chief Wahoo bobblehead dolls.[50]

A 1999 editorial reported annual revenue of $1.5 million from sales of licensed merchandise, and $15 million from sales at official team shops.[51] An interview subject in a 2006 documentary on Chief Wahoo estimated that the logo brought in over $20 million per year.[52]

Depiction on Cleveland uniforms

[edit]

Although the club had adopted the name "Indians" during the 1915 season, there was no acknowledgment of this nickname on their uniforms until 1928. In the years between the team's 1901 formation and the 1927 season, uniforms contained variations on a stylized "C" or the word "Cleveland" (except the 1921 season,[53] when the front of the club's uniform shirts read "Worlds [sic] Champions"). The 1928 season saw modified club uniforms whose left breast bore a patch depicting the profile of a headdress-wearing American Indian.[54] In 1929, a smaller version of that same patch migrated to the home uniform sleeve, where similar incarnations of the early design remained through 1938. The online gallery of historical Cleveland uniforms does not accurately depict the evolution of the pre-Wahoo logo,[55] a cartoon depiction of a man in a warbonnet drawn in profile.[56] Patrick Hruby, writing for ESPN, described an early image featuring these uniforms as "a far cry from Chief Wahoo and other grinning caricatures".[57]

For 1939, the club wore the Baseball Centennial patch on the sleeve. Various other patches were worn for the next few years, none of them featuring Native American caricatures.[58] In 1946, the last year before Chief Wahoo's introduction, both the home and road shirts featured a City of Cleveland Sesquicentennial patch.

In 1947, home and road uniforms began featuring the first incarnation of Chief Wahoo. The new logo, a caricature drawn from a three-quarter perspective, supplanted the earlier profile drawings. A redesigned Chief Wahoo caricature appeared on the uniform shirt sleeve starting in 1951.[59] Uniform designs have varied in the years since, but the 1951 design was used in most years since then, its only notable change being the addition of blue outlines in 1979.[1] Exceptions include the 1972 uniform, which featured no Chief Wahoo logo, and the 1973–1978 uniforms, which featured a modified logo with Chief Wahoo at bat.[60][61] Chief Wahoo was featured on Cleveland hats from 1951 to 1958,[62] and returned to Cleveland's hats in 1986,[23] following an increase in the size of the logo on uniforms sleeves in 1983.[62] By 2013, Chief Wahoo was featured on every variation of the team's uniforms.[31]

On January 29, 2018, the Cleveland Indians announced they would remove the Chief Wahoo logo from their on-field baseball caps and jerseys starting with the 2019 season.[4] On March 21, 2018, the Baseball Hall of Fame announced that Chief Wahoo would no longer be featured on future Hall of Fame plaques, starting with newly inducted Jim Thome as an Indian.[6] The Chief Wahoo logo was last worn by the Indians in an 11–3 loss to the Houston Astros during the ALDS on October 8, 2018. Coincidentally, the game fell on Indigenous Peoples' Day.[17]

Alternative logos

[edit]The Indians introduced alternative logos: a block-letter "C", a script-letter "I", and the word "Indians" written in script. In 2013, the organization officially changed the primary logo from Chief Wahoo to the recently introduced block "C". Previously, team spokesman Bob DiBiasio had described the block-C logo as alternative to Chief Wahoo: "We have added a logo, the block C, recently in addition to the Wahoo logo and the script 'Indians'. Fans of the team have alternative ways to express their support."[63] In 2002, DiBiasio described an Indians hat with the letter "I" in similar terms, as official merchandise that provides an alternative without Chief Wahoo.[64] Owner Larry Dolan had said the alternative logos are "another marketing tool" and "it's not true" that they are a means of phasing out Chief Wahoo.[65] The Encyclopedia of Sports Management and Marketing has described the new hats and team mascot Slider as "an effort to distance the franchise from the controversy".[66]

Notable uses of alternate logos

[edit]

The use of these alternative logos has at times proved newsworthy. In 1994, when then-President Bill Clinton threw the first pitch at Jacobs Field, he wore a hat with the letter-C logo worn from 1978 to 1985 instead of Chief Wahoo.[67][68][69] A White House aide described the decision as one taken "in recognition of the sensitivities" involved,[67] and it spurred public debate on the issue of Native American names and images in sports.[68] One critic accused Clinton of "an apparent attempt to appease his 'politically correct' constituency".[70]

When Cleveland played Baltimore in the 2007 "Civil Rights Game" in Memphis, logos were removed from the uniforms of both teams.[71] This caused some sportswriters to assert that the office of the Major League Baseball commissioner understood "on some level, that Chief Wahoo is the wrong message".[71] The controversy was heightened by Memphis' location on the Trail of Tears.[71] The president of the Faraway Cherokees in Memphis said, "My family was on the Trail of Tears. We feel offended that they would bring a team here called the Indians. It's racist. We aren't gone."[71]

Chief Wahoo was also absent from merchandise sold at FanFest activities during the 2013 MLB All-Star Game in New York City.[72][73] The use of alternate logos on official merchandise led sportswriters to speculate that Major League Baseball was uncomfortable or cautious about using the Chief Wahoo logo.[72][73] Major League Baseball's use of an alternate logo on its website has led to similar speculation.[74]

Use during spring training

[edit]

In 2009, when the Cleveland Indians moved their spring training operations to Goodyear, Arizona, the Chief Wahoo logo was not used on the outside of the local stadium where they practiced. The Chief Wahoo logo had been prominently displayed at the team's previous spring training facilities in Winter Haven, Florida.[75] Explaining that Wahoo's absence from the city-owned Goodyear Ballpark had not been the team's decision, then-team president Paul Dolan said, "It's not our ballpark. I would expect some sensitivity was involved, but ultimately it's the city's ballpark."[76] A city spokesperson said that they were following Cleveland's marketing lead after the team used the script "I" logo on the player development complex in addition to the ballpark.[76] Dolan said there was also "some sensitivity involved" with player development complex.[76] The logo is also absent from team property and employee clothing in Arizona.[77]

Cleveland sportswriter Paul Hoynes wrote that the Chief Wahoo logo was not used in Goodyear "because of the heavy population of Native Americans in Arizona."[78] According to the 2010 census, the Arizona population is 4.6% Native American or Alaska Native, compared to 0.4% in Florida and 0.2% in Ohio.[79] Sportswriter Craig Calcaterra described the issue more bluntly, saying that "in the southwest there is a much larger Indian population than there is back in Ohio and that not putting up a big racist, comically-exaggerated red-faced logo of an Indian is simply a matter of common courtesy."[77] In 2013, Chief Wahoo was still used on the Cleveland Indians' spring training web page, where the logo was framed within the name of their host city,[80] but has since been replaced.

"Stars and stripes" logo variant

[edit]

In 2008, Major League Baseball introduced special caps with each team's cap logo woven into the "Stars and Stripes" that were worn during major American holidays. The Indians cap with Chief Wahoo emblazoned in stars and stripes was criticized by some sportswriters. In 2009, MLB redesigned the Indians "Stars and Stripes" cap with a "C" logo replacing Chief Wahoo.[81]

Similar events played out several years later. In 2013, manufacturer New Era released an image of a hat with a flag-themed Chief Wahoo to be worn by the team on the Fourth of July. According to a source at Major League Baseball, the image was mistakenly released because of a misunderstanding that all teams would be using their main logo. After news reports criticized the "short-sightedness of covering a Native American logo with stars and stripes" and said it looked "a little too much like a blackface cartoon", New Era removed the design and released an image of a flag-themed block-C logo hat that would be worn instead.[82][83][84] Some speculated that the scrapped design may actually have been intended for use.[85][86] Local alternative news magazine The Cleveland Scene called it "the most offensive Cleveland Indians hat ever".[87]

Folk art and fan art

[edit]Chief Wahoo has also appeared in numerous works of folk art and fan art. A 2002 decision by the US Department of Labor Employees' Compensation Appeals Board described the actions of a former letter carrier who claimed to have produced over 3,000 pieces of Chief Wahoo yard art, although she later said that claim was an exaggeration.[88] The former letter carrier also produced Chief Wahoo clocks.[88] In 2006, a likeness of Chief Wahoo took third place in a local sand sculpture competition, finishing behind sand sculpture versions of King Neptune and a man in a swimming pool.[89]

In Meadville, Pennsylvania, the adult children of a 74-year-old Cleveland Indians fan hired chainsaw artist Brian Sprague to carve a 7-foot (2.1 m)-tall maple tree stump into a full-body statue of Chief Wahoo.[90][91][92] In 2007, a newspaper in Toledo, Ohio reported that a man from the Toledo suburb of Oregon intended to have a tree trunk carved into a depiction of Chief Wahoo at bat.[50]

Elements of Chief Wahoo were incorporated into a collage that appeared in the Tribe Tract & Testimonial,[62][93] a fanzine that is now collected at the Cleveland Public Library.[94] In 2013, a Cleveland artist designed a T-shirt that combined Chief Wahoo's feather with imagery from the Cleveland Browns of the NFL and the Cleveland Cavaliers of the NBA.[95]

In 1987, Cleveland players Joe Carter and Cory Snyder were scheduled to appear on the cover of Sports Illustrated posed in front of a stained-glass rendition of Chief Wahoo.[96] However, the stained-glass logo was not ultimately used on the cover.[97] The unused concept was described in a Los Angeles Times article that did not clearly state whether the stained-glass logo was an amateur or professional work.[96] Fan artists have incorporated Chief Wahoo's likeness into stained glass pieces.[98]

Other depictions

[edit]In 2011, artist Cyprien Gaillard installed Neon Indian, a 12-metre (39 ft), neon-outline Chief Wahoo replica atop the abandoned Haus der Statistik building in Berlin's Mitte district.[99] The Wall Street Journal said that the project "combines a symbol of the American Rust Belt with a souvenir of Communist town planning", and was "meant to reflect on the broader subject of urban decline."[100]

In another work, titled Indian Palace, Gaillard silkscreened the logo onto a salvaged window from East Berlin's demolished Palast der Republik.[101] The work appeared in an exhibition whose curator described the piece in terms of power, hierarchies, and values: "The window panes have arrived as 'spoils' in Frankfurt. The term 'spoil' originally referred to the hide of an animal or the enemy's armor and was later extended to apply to old fragments of architecture. The Native American grinning through the shimmering glass brings to mind the constant change in power relations, hierarchies and values."[101] In an article on Gaillard's work, Indian Country Today Media Network said it was up to the viewer to decide "whether it is a clever re-imagining of a controversial symbol or merely a callous and harmful repetition."[102]

Controversy

[edit]As part of the Native American mascot controversy, Chief Wahoo has drawn particular criticism. The use of "Indians" as the name of a team was also part of the controversy, and led over 115 professional organizations representing civil rights, educational, athletic, and scientific experts to publish resolutions or policies stating that any use of Native American names or symbols by non-native sports teams is a harmful form of ethnic stereotyping that promotes misunderstanding and prejudice and contributes to other problems faced by Native Americans.[103] In 2021, the team announced their rebranding as the Cleveland Guardians for the 2022 season.[104]

Opponents have been protesting and taking other actions against the name and logo since the 1970s. The team owners and management have defended their use as having no intent to offend but to honor Native Americans, upholding many fans' beliefs and continued support.[3] However, the use of Chief Wahoo was de-emphasized in favor of alternate logos beginning in the 2010s.[105][106] The logo was subsequently retired after the 2018 season, and "is no longer appropriate for on-field use", according to MLB commissioner Rob Manfred.[107] However, as to maintain their trademarks on the logo, along with the words "Tribe" and "Wahoo", and prevent their dilution, the team continued to sell limited merchandise with Chief Wahoo only at its physical team store.[108][109] Chief Wahoo was also not featured on the playing field when the Cleveland Indians hosted the 2019 All-Star Game.[110][111]

See also

[edit]- Native American name controversy

- Chief Noc-A-Homa

- Golliwog

- List of sports team names and mascots derived from Indigenous peoples

- List of ethnic sports team and mascot names (all ethnicities)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Wong, Stephen; Grob, Dave (2016). Game Worn: Baseball Treasures from the Game's Greatest Heroes and Moments. Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 9781588345714. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ Bastian, Jordan (January 29, 2018). "Indians to stop using Wahoo logo starting in '19". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ a b c Waldstein, David (January 29, 2018). "Cleveland Indians Will Abandon Chief Wahoo Logo Next Year". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Siemaszko, Corky (January 29, 2018). "Cleveland Indians will remove Chief Wahoo logo in 2019". NBC News. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "HALL OF FAME STATEMENT ON JIM THOME'S PLAQUE LOGO". BaseballHall.org (Press release). March 21, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ a b "Thome HOF plaque won't feature Chief Wahoo". ESPN.com. March 21, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Ricca, Brad (June 19, 2014). "The Secret History of Chief Wahoo". Belt Magazine. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Foster, Gayle (April 15, 2012). "All hail to the 'chief': Wahoo designer visits Emeritus". The Post (Medina, Ohio). Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Pattakos, Peter (April 25, 2012). "The Curse of Chief Wahoo: Are we paying the price for embracing America's last acceptable racist symbol?". The Cleveland Scene. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved May 17, 2013.

- ^ a b c Netzel, Andy; Goldbach, Walter (August 2008). "Life According to Walter Goldbach". Cleveland Magazine.

- ^ Affleck, John (May 28, 1999). "Owner to Decide Fate of Chief Wahoo". APNews.com. Associated Press. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- ^ "Why are the Cleveland Indians called the Indians?". Cleveland.com. January 29, 2018.

- ^ "Louis Sockalexis' Tribe Angry About Chief Wahoo, Logo Obviously Does Not "Honor" His Legacy". Cleveland Scene. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Pluto, Terry (2007). The Curse of Rocky Colavito: A Loving Look at a Thirty-Year Slump. Gray & Company, printing by Simon & Schuster. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-59851-035-5.

- ^ Baer, Bill (October 8, 2018). "Indians choose to wear Chief Wahoo on Indigenous Peoples' Day, get swept out of ALDS". nbcsports.com. NBC Sports. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ^ Hannon, Elliot (October 9, 2018). "Cleveland Indians Play Final Game With Grinning Native American Caricature "Chief Wahoo" Logo". Slate. The Slate Group. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ^ a b Hart, Torrey (October 8, 2018). "Cleveland Indians use Chief Wahoo logo one last inappropriate time". Yahoo Sports. Yahoo. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c Fleitz, David (2002). Louis Sockalexis and the Cleveland Indians. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 187. ISBN 0-7864-1383-2.

- ^ a b Staurowsky, Ellen J. (1998). "Searching for Sockalexis: Exploring the Myth at the core of Cleveland's 'Indian' Image". In Altherr, Thomas L.; Hall, Alvin L. (eds.). The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 1998. McFarland. pp. 138–153. ISBN 9780786409549. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ a b "New Scoreboard Set for Cleveland Park". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- ^ "Chief Wahoo cheers HR in Cleveland stadium (photo caption)". Youngstown-Vindicator. April 23, 1978. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- ^ Wulf, Steve (January 28, 1985). "Baseball's Dutch Treat". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ^ a b Fleitz, David. "Chief Wahoo, Revisited". Archived from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ McGimpsey, David (2000). Imagining Baseball: America's Pastime and Popular Culture. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 98. ISBN 0-253-33696-1.

- ^ a b Schneider, Russel (2004). The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, L.L.C. p. 370. ISBN 1-58261-840-2.

- ^ Bjarkman, Peter C. (1991). Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball Team Histories: The American League. Mecklermedia Corporation. p. 127. ISBN 9780887363733.

- ^ "Russell Means and Juanita Helphrey discuss the Cleveland Indians and Chief Wahoo". The Morning Exchange. 1994. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ Sheeran, Thomas J. (July 2, 1993). "Indians will keep logo, despite objections". Deseret News. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ "Chief Wahoo's Domain is Still Turbulent". The New York Times. Associated Press. July 2, 1993. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ McNichol, Tom (July 6, 1997). "A Major-League Insult?". The Kingman Daily Miner. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Podolski, Mark (May 5, 2013). "Chief Wahoo still a divisive symbol in Cleveland sports". The Morning Journal. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ^ Podolski, Mark (May 6, 2013). "Video interview with John J. Grabowski, published in the article "Chief Wahoo caricature controversy still hot topic for Cleveland Indians, Native Americans"". The News-Herald. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ Western Reserve Historical Society. "Cleveland's Chief Wahoo Lights Up with a Smile". Archived from the original on May 4, 2013. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ^ "Staff at Western Reserve Historical Society". Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ^ Sheehan, Michael (September 1, 2006). "Battle Flag of USS Cleveland retired at Jacobs Field". US Navy. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- ^ "Water tower's Wahoo mug to receive delicate face-lift". Lakeland Ledger. November 3, 1993. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "Spring Training 2008: The Cleveland Indians Say Good-Bye To Winter Haven, Fla". The Chattahoogan. March 22, 2008. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ Sargent, Scott (March 12, 2009). "Indians Leave Florida, but Wahoo Still Remains". Waiting for Next Year.

- ^ "Winter Haven unveils water tower, city pride". Polk State College. April 27, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "Walter Goldbach, creator of Chief Wahoo logo, dies at 88". wkyc.com. December 15, 2017.

- ^ "Cleveland Indians, Chief Wahoo statue plus Rempel doll". Cowan Auctions. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ "The Mercury from Pottstown, Pennsylvania on December 16, 1949 · Page 12". Newspapers.com. December 16, 1949.

- ^ Tanier, Mike (May 16, 2013). "The All-Time Worst Mascot Fails". Sports on Earth. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Marks, Craig (August 18, 2011). "Fired-up Tribe ready to battle Tigers". West Side Leader. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ "Chief Wahoo Chocolate Bar Debuts". June 17, 2005. Archived from the original on June 5, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- ^ "Wahoo Women". Cleveland Indians / Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- ^ "Cleveland Indians, Domino's partner on new 'Wahoo Wednesdays' promotion". Cleveland Indians / Major League Baseball. March 4, 2013. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- ^ Kaduk, Kevin (August 7, 2012). "The 18 creepiest caps for sale on MLB.com". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ "Cleveland Indians 'Slider' Mascot Cap". Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ a b Silka, Zach (October 3, 2007). "300 bobble heads reflect Tribe pride for Cleveland fan from Oregon". The Toledo Blade. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ "Chief Wahoo needs an early retirement". The Lantern. April 7, 1999. Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ Greening, Bryant (November 11, 2006). "Filmmaker screens attack on Tribe's Chief Wahoo". The Athens News. Archived from the original on December 29, 2007. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ "Cleveland uniforms in 1921". Exhibits.baseballhalloffame.org. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ "National Baseball Hall of Fame — Dressed to the Nines — Uniform Database". exhibits.baseballhalloffame.org.

- ^ "National Baseball Hall of Fame — Dressed to the Nines — Uniform Database". exhibits.baseballhalloffame.org.

- ^ "Bob Feller: Videos of one of baseball's best-ever pitchers and ambassadors". December 17, 2010.

- ^ Hruby, Patrick (November 17, 2009). "Capturing America's sports history". ESPN. Archived from the original on January 11, 2010. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ "Cleveland uniforms, 1901–1950". Exhibits.baseballhalloffame.org. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Okkonen, Mark (December 1993). Baseball Uniforms of the 20th Century. Sterling Publishing Company. pp. 37, 190. ISBN 0-8069-8491-0.

- ^ "Cleveland uniforms, 1947–1985". Exhibits.baseballhalloffame.org. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ A comprehensive gallery of Cleveland Indians logos can be seen here [1].

- ^ a b c Nevard, David. "Wahooism in the USA". Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ Sangiacomo, Michael (April 1, 2012). "Native Americans to mark Cleveland Indians 1st games with annual protest of Chief Wahoo logo". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Barrientos, Tonya (March 16, 2002). "A chief beef: Some teams still seem insensitive to Indians". Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 18, 2004. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Hanson, Dan (2006). "Interview with Larry Dolan". Great Lakes Geek. pp. 7:22–9:15. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ Linda E. Swayne and Mark Dodds, ed. (2011). Encyclopedia of Sports Management and Marketing, Volumes 1–4. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc. p. 223. ISBN 978-1-4129-7382-3. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ a b Jehl, Douglas (April 5, 1994). "Clinton's Doubleheader: Two Cities, Two Sports". The New York Times. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Zografos, Daphne (2010). Intellectual Property and Traditional Cultural Expressions. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. pp. 90–91.

- ^ Kepner, Tyler (April 5, 2010). "From Taft to Obama, Ceremonial First Pitches". The New York Times. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ Rhode, John B. (Fall 1994). "The Mascot Name Change Controversy: A Lesson in Hypersensitivity". Marquette Sports Law Review. 5 (1): 141–160. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Bondy, Filip (March 8, 2007). "Selig's uncivil wrong". New York Daily News. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Allard, Sam (July 17, 2013). "There Were No Chief Wahoo Hats at All-Star Game FanFest". Cleveland Scene. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ a b Neyer, Rob (July 16, 2013). "FanFest and what it might say about Chief Wahoo". SB Nation. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ Calcaterra, Craig (June 4, 2012). "The incremental marginalization of Chief Wahoo continues". NBC Sports Hardball Talk. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ Liscio, Stephanie (May 13, 2011). "Cap week: Time to retire Chief Wahoo". ESPN Sweet Spot. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Cleveland Indians' Chief Wahoo logo left off team's ballpark, training complex in Goodyear, Ariz". Cleveland Plain Dealer. April 12, 2009. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ a b Calcaterra, Tim (March 8, 2012). "Scenes from Spring Training: My annual Chief Wahoo observation". NBC Sports. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ Hoynes, Paul (May 18, 2013). "Will the AL and NL ever agree on the DH? Hey, Hoynsie!". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "Cleveland Indians Spring Training". Cleveland Indians / Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on March 7, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ "MLB pulls Chief Wahoo off Cleveland's '09 Stars and Stripes cap". Yahoo!. May 20, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2009.

- ^ Gaines, Cork (June 4, 2013). "[UPDATE] Cleveland Indians Will Not Be Wearing Offensive Cap After All". Business Insider. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ Axisa, Mike (June 6, 2013). "MLB smartens up, scraps offensive Chief Wahoo hat for Fourth of July". CBS Sports. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ ICTMN Staff (June 6, 2013). "Cleveland Indians 'Chief Wahoo' Fourth of July Hat Replaced". Indian Country Today Media Network. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ Calcaterra, Craig (June 6, 2013). "MLB axes the Chief Wahoo July 4th cap design". NBC Sports Hardball Talk. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ Lukas, Paul (June 6, 2013). ""C" No Evil". Uni-Watch. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ Allard, Sam (June 6, 2013). "The Most Offensive Cleveland Indians Hat Ever". The Cleveland Scene. Archived from the original on June 9, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ a b "In the Matter of JANE A. PASTVA and U.S. POSTAL SERVICE, POST OFFICE, Warren, OH; Docket No. 02-1141; Submitted on the Record; Issued December 11, 2002". US Department of Labor. December 11, 2002. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Dillaway, Warren (August 4, 2006). "Families unite in competition to see who can create the best sculpture". The Star Beacon. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Briggs, David (September 4, 2007). "A stump only a Tribe fan could love: Daughter's thoughtful gift turns an eyesore into a treasure". Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on November 1, 2007. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ WKYC-TV (March 31, 2008). "Ugly tree stump turned into Wahoo shrine for Tribe fan". WKYC News. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Turrisi, T.J. (August 13, 2007). "Indians fan gets permanent visit from mascot". Meadville Tribune. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Nevard, David. "Book Review: Time Stops". Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ^ Worldcat listing for Tribe Tract & Testimonial. Worldcat. OCLC 609852351.

- ^ Livingston, Tom (August 9, 2013). "Etch-A-Sketch artwork leads to GV Art + Design retail store in Lakewood". WEWS-TV News Channel 5. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ a b Crowe, Jerry (March 22, 1987). "A Bright Star Is Rising Over Cleveland : Cory Snyder Has Gone From College Ranks to MVP Candidate in 3 Years". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ "Picture of SI cover". www.boston.com. 1987. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ Lovano, John A. "Stained Image thumbnails". Archived from the original on March 22, 2011.

- ^ Suttel, Scott (July 29, 2011). "Talk about a long road trip – Chief Wahoo's in Berlin". Crain's Cleveland Business. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ^ Marcus, J.S. (July 29, 2011). "Contemporary Art and Economics in Berlin". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ^ a b "Exhibition and Karl Ströher Prize for French Artist Cyprien Gaillard". Art Daily. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ ICTMN Staff (August 3, 2011). "Why Is this Indian Smiling—in Berlin?". Indian Country Today Media Network. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ "Legislative efforts to eliminate native-themed mascots, nicknames, and logos: Slow but steady progress post-APA resolution". American Psychological Association. August 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ Lyons, Matt (July 23, 2021). "Cleveland unveils new team name, logos: Cleveland Guardians". Covering the Corner. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ^ Pluto, Terry (April 1, 2016). "Cleveland Indians owner Paul Dolan says team is keeping Chief Wahoo, but not as main logo – Terry Pluto". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Webb, Craig (October 8, 2016). "Indians mascot Chief Wahoo relegated to the bench at Progressive Field". Akron Beacon-Journal. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Bogage, Jacob (October 9, 2018). "The Cleveland Indians' season is over, and so is Chief Wahoo's 71-year run". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ Blackburn, Pete (November 19, 2018). "Cleveland Indians fully phase out Chief Wahoo logo, unveil new uniforms for 2019". CBS News. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ Barnett, David (June 28, 2019). "Ejected From the Field, Chief Wahoo's Still A Hot Seller". Ideastream (WCPN). Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ Lacques, Gabe. "Opinion: Chief Wahoo missing from Cleveland's All-Star Game, but mascot issue endures". USA TODAY.

- ^ Pedone, Nick. "As the All-Star Game Goes on Without Chief Wahoo, Local Groups Say They'll Continue Pushing for Indians to Change Name". Cleveland Scene. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

External links

[edit]- 20th-century controversies in the United States

- Anti-Indigenous racism in Ohio

- Stereotypes of Native American people

- Native American cultural appropriation

- Cleveland Guardians

- Fictional Native American people

- Major League Baseball controversies

- Major League Baseball team mascots

- Native American topics

- Native American-related controversies

- Mascots introduced in 1951

- Native American mascots