SpaceX Dragon

| Manned and cargo Drago spacecraft (artist's impression) | |

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Role | Placing humans and cargo into Low Earth orbit (commercial use)[1] ISS resupply (governmental use) |

| Crew | None (cargo version) 7 (DragonRider version) |

| Launch vehicle | Falcon 9 |

| Dimensions | |

| Height | 6.1 meters (20 feet)[2] |

| Diameter | 3.7 meters (12.1 feet)[2] |

| Sidewall angle | 15 degrees |

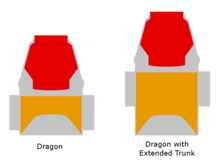

| Volume | 10 m3 / 245 ft3 pressurized[3] 14 m3 / 490 ft3 unpressurized[3] 34 m3 / 1,200 ft3 unpressurized with extended trunk[3] |

| Dry mass | 4,200 kg (9,260 lb)[2] |

| Payloads | 6,000 kg / 13,228 lb (launch)[3] 3,000 kg / 6,614 lb (return)[3] |

| Performance | |

| Endurance | 1 week to 2 years[3] |

| Re-entry at | 3.5 Gs[4][5] |

The Dragon is a reusable spacecraft developed by SpaceX, a private space transportation company based in Hawthorne, California. During its uncrewed maiden flight in December 2010, Dragon became the first commercially-built and operated spacecraft to be recovered successfully from orbit.[6] On 25 May 2012, an uncrewed variant of Dragon became the first commercial spacecraft to successfully rendezvous with the International Space Station (ISS).[7][8][9][10]

SpaceX is contracted to deliver cargo to the ISS under NASA's Commercial Resupply Services program, and Dragon is scheduled to begin regular cargo flights in September 2012.[11][12] Additionally, NASA awarded SpaceX a Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) contract in April 2011. The Dragon is planned to carry up to seven astronauts, or a combination of personnel and cargo, to and from low Earth orbit. The Dragon's heat shield is furthermore designed to withstand Earth re-entry velocities from potential Lunar and Martian spaceflights.[13]

General characteristics

The Dragon consists of a nose-cone cap that jettisons after launch, a conventional blunt-cone ballistic capsule, and a trunk equipped with two solar arrays.[14] The capsule utilizes a PICA-X heat shield – based on a proprietary variant of NASA's phenolic impregnated carbon ablator (PICA) material – designed to protect the capsule during Earth atmospheric reentry, even at high return velocities from Lunar and Martian destinations.[13][15][16] The Dragon capsule is re-usable, and can be flown on multiple missions.[14] However, the trunk is not recoverable; it separates from the capsule before re-entry and burns up in Earth's atmosphere.

The Dragon spacecraft is launched atop a Falcon 9 booster.[17] The Dragon capsule is equipped with 18 Draco thrusters, dual-redundant in all axes: any two can fail without compromising the vehicle's control over its pitch, yaw, roll and translation.[15] During its initial cargo and crew flights, the Dragon capsule will land in the Pacific Ocean and be returned to the shore by ship.[18] However, SpaceX plans to eventually install deployable landing gear and use eight upgraded SuperDraco thrusters to perform a solid earth propulsive landing.[19][20][21]

Name

SpaceX's CEO, Elon Musk, named the spacecraft after the 1963 song "Puff, the Magic Dragon" by Peter, Paul and Mary, reportedly as a response to critics who considered his spaceflight projects impossible.[22]

Production

In December 2010, the SpaceX production line was reported to be manufacturing one new Dragon spacecraft and Falcon 9 rocket every three months. By 2012, production turnover had increased to one every six weeks.[23]

Projects

NASA Commercial Resupply Services program

Development started on the Dragon capsule in late 2004.[24] In 2005, NASA began its Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) development program, soliciting proposals for a commercial ISS resupply spacecraft to replace its now-retired Space Shuttle. The Dragon spacecraft was part of SpaceX's proposal, submitted to NASA in March 2006. SpaceX's COTS proposal was issued as part of a team, which also included MD Robotics, the Canadian company that had built the ISS's Canadarm2.

On 18 August 2006, NASA announced that SpaceX had been chosen, along with Kistler Aerospace, to develop cargo launch services for the ISS.[25] The initial plan called for three demonstration flights of SpaceX's Dragon capsule to be conducted between 2008 and 2010.[26][27] SpaceX and Kistler were to receive up to $278 million and $207 million respectively,[27] if they met all NASA milestones, but Kistler failed to meet its obligations, and its contract was terminated in 2007.[28] NASA later re-awarded Kistler's contract to Orbital Sciences.[28][29]

NASA awarded a $1.6 billion Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) to SpaceX on 23 December 2008, with options that potentially increase the maximum contract value to $3.1 billion.[30] The contract calls for 12 flights to the ISS, with a minimum of 20,000 kg (44,000 lb) of cargo carried to the ISS.[30]

On 23 February 2009, SpaceX announced that its chosen heat shield material, PICA-X, had passed heat stress tests in preparation for the Dragon's maiden launch.[31] PICA-X is reportedly ten times cheaper to manufacture than NASA's PICA heat shield material.[32]

The primary proximity-operations sensor for the Dragon spacecraft, the DragonEye, was tested in early 2009 during the STS-127 mission, when it was mounted near the docking port of the Space Shuttle Endeavour and used while the shuttle approached the International Space Station. The DragonEye's LIDAR and thermal imaging capabilities were both tested successfully.[33][34] The COTS UHF Communication Unit (CUCU) and Crew Command Panel (CCP) were delivered to the ISS during the late 2009 STS-129 mission.[35] The CUCU allows the ISS to communicate with Dragon and the CCP allows ISS crew members to issue basic commands to Dragon.[35] In summer 2009, SpaceX hired former NASA astronaut Ken Bowersox as vice president of their new Astronaut Safety and Mission Assurance Department, in preparation for crews using the spacecraft.[36]

Demonstration flights

The first flight of the Falcon 9 occurred in June 2010 and launched a stripped-down version of the Dragon capsule. This Dragon Spacecraft Qualification Unit was initially used as a ground test bed to validate several of the capsule's systems. During the flight, the unit's primary mission was to relay aerodynamic data captured during the ascent.[37][38] It was not designed to survive re-entry, and did not.

On 22 November 2010, NASA announced that the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) had issued a reentry license for the Dragon capsule, the first such license ever awarded to a commercial vehicle.[39] The first Dragon spacecraft launched on its first mission, COTS Demo Flight 1, on 8 December 2010, and was successfully recovered; the mission furthermore marked the second flight of the Falcon 9.[40] The DragonEye sensor flew again on STS-133 in February 2011 for further on-orbit testing.[41]

In December 2011, NASA approved SpaceX's decision to combine the COTS 2 and 3 mission objectives into one Falcon 9/Dragon flight, COTS 2+, which launched successfully on 22 May 2012.[42][8] Dragon conducted orbital tests of its navigation systems and abort procedures, before being grappled by the ISS' Canadarm2 and successfully berthing with the station on 25 May to offload its cargo.[7][43][44][45][46] Dragon returned to Earth on 31 May 2012, landing as scheduled in the Pacific Ocean, and was successfully recovered.[47][48]

CRS Dragon design

For the CRS variant of Dragon, the ISS's Canadarm2 grapples its Flight-Releasable Grapple Fixture and berths Dragon to the station's US Orbital Segment using a Common Berthing Mechanism.[49] The capsule does not have an independent means of maintaining a breathable atmosphere for astronauts and instead circulates in fresh air from the ISS.[50] For typical missions, Dragon is planned to remain berthed to the ISS for about 30 days, similar to the Japanese HTV uncrewed vehicle.[51] The CRS Dragon's capsule can transport 3,310 kilograms (7,300 lb) of pressurized cargo to the ISS in a volume of 6.8 cubic metres (240 cu ft) and return 2,500 kilograms (5,500 lb) of cargo in that same volume.[52] The CRS Dragon's trunk can transport 3,310 kilograms (7,300 lb) of unpressurized cargo in a volume of 14 cubic metres (490 cu ft), and can dispose of 2,600 kilograms (5,700 lb) of waste in that same volume by destructive re-entry.[52]

List of COTS/CRS missions

List includes only currently manifested missions. All CRS missions are currently planned to be launched from Cape Canaveral Launch Complex 40.

| Mission name | Launch date | Remarks | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| COTS Demo Flight 1 | 8 December 2010[53] | First Dragon mission (no trunk was attached), second Falcon 9 launch | Success[6] |

| COTS Demo Flight 2+ | 22 May 2012[8] | First Dragon mission with complete spacecraft, first rendezvous mission and first berthing mission with ISS | Success[47] |

| Dragon C3 | 24 September 2012[11] | First CRS mission, first non-demo mission | |

| Dragon C4 | 15 December 2012[11] | ||

| SpX-3 | TBA | Hardware scheduled to arrive at launch site in 2013[54] | |

| SpX-4 | TBA | Hardware scheduled to arrive at launch site in 2013[54] | |

| SpX-5 | TBA | Hardware scheduled to arrive at launch site in 2014[54] | |

| SpX-6 | TBA | Hardware scheduled to arrive at launch site in 2014[54] | |

| SpX-7 | TBA | Hardware scheduled to arrive at launch site in 2014[54] | |

| SpX-8 | TBA | Hardware scheduled to arrive at launch site in 2015[54] | |

| SpX-9 | TBA | Hardware scheduled to arrive at launch site in 2015[54] | |

| SpX-10 | TBA | Hardware scheduled to arrive at launch site in 2015[54] | |

| SpX-11 | TBA | Hardware scheduled to arrive at launch site in 2015[54] | |

| SpX-12 | TBA | Hardware scheduled to arrive at launch site in 2015[54] |

NASA Commercial Crew Development program

SpaceX was not awarded funding during the first phase of NASA's Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) milestone-based program. However, the company was selected on 18 April 2011, during the second phase of the program, to receive an award valued at $75 million to help develop its crew system.[55][56]

Their CCDev2 milestones involve the further advancement of the Falcon 9/Dragon crew transportation design, the advancement of the Launch Abort System propulsion design, completion of two crew accommodations demos, full-duration test firings of the launch abort engines, and demonstrations of their throttle capability.[57] NASA is aiming to be able to regularly fly commercial vehicles to the ISS by 2016.[58]

SpaceX's launch abort system received preliminary design approval from NASA in October 2011.[59] In December 2011, SpaceX performed its first crew accommodations test; the second such test is expected to involve spacesuit simulators and a higher-fidelity crewed Dragon mock-up.[60][61] In January 2012, SpaceX successfully conducted full-duration tests of its SuperDraco landing/escape rocket engine at its Rocket Development Facility in McGregor, Texas.[62]

In 2006, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk stated that SpaceX had built "a prototype flight crew capsule, including a thoroughly tested 30-man-day-life-support system".[24] A video simulation of this escape system's operation was released in January 2011.[20] According to Musk, the developmental cost of a crewed Dragon and Falcon 9 would be between $800 million and $1 billion.[63] In 2009 and 2010, Musk suggested on several occasions that plans for a crewed variant of the Dragon were proceeding and had a two-to-three-year timeline to completion.[64][65] SpaceX has submitted a bid for the third phase of CCDev, CCiCap, awards for which are expected to be announced in the summer of 2012.[66][67]

DragonRider design

DragonRider, the crewed variant of Dragon, will support a crew of seven or a combination of crew and cargo.[68][69] It is planned to be able to perform fully autonomous rendezvous and docking with manual override capability; and will use the NASA Docking System (NDS) to dock to the ISS.[14][70] For typical missions, DragonRider would remain docked to the ISS for a period of 180 days; it is required to be able do so for 210 days, the same as the Russian Soyuz spacecraft.[71][72] SpaceX plans to use an integrated pusher launch escape system for the Dragon spacecraft, with several claimed advantages over the tractor detachable tower approach used on most prior crewed spacecraft.[73][74][58] These advantages include the provision for crew escape all the way to orbit, reusability of the escape system, improved crew safety due to the elimination of a stage separation, and the ability to use the escape engines during the landing phase for a precise solid earth landing of the Dragon capsule.[75] An emergency parachute will be retained as a redundant backup for water landings.[75] The Paragon Space Development Corporation is assisting in the development of DragonRider's life support system.[76]

At a NASA news conference on 18 May 2012, SpaceX confirmed that their target launch price for crewed Dragon flights is $140,000,000, or $20,000,000 per seat if the maximum crew of 7 is aboard. This contrasts with the current Soyuz launch cost of $63,000,000 per seat.[77]

DragonLab

When used for non-NASA, non-ISS commercial flights, the uncrewed version of the Dragon spacecraft is named DragonLab.[14] It is reusable, free-flying, and is capable of carrying both pressurized and unpressurized payloads. Its subsystems include propulsion, power, thermal and environmental control, avionics, communications, thermal protection, flight software, guidance and navigation systems, and entry, descent, landing, and recovery gear.[3] It has a total combined up-mass of 6,000 kilograms (13,000 lb) upon launch, and a maximum downmass of 3,000 kilograms (6,600 lb) when returning to Earth.[3] As of November 2011[update], there are two DragonLab missions listed on the SpaceX launch manifest: one in 2014 and another in 2015.[78]

Red Dragon

Red Dragon is a concept for a low-cost Mars lander that would utilize a SpaceX Falcon Heavy launch vehicle and a modified Dragon capsule to enter the Martian atmosphere. The concept will be proposed for funding in 2012/2013 as a NASA Discovery mission, for launch in 2018.[79][80] The mission would search for the biosignatures of past or present life on Mars. Red Dragon would drill about 3.3 feet (1.0 m) underground in an effort to sample reservoirs of water ice known to exist in the shallow Martian subsurface.[79][80]

A Dragon capsule is capable of performing all the entry, descent and landing (EDL) functions required to deliver payloads of 1 tonne (2,200 lb) or more to the Martian surface without using a parachute. It is thought that the capsule's own drag may slow it sufficiently for the remainder of its descent to be within the capabilities of its retro-propulsion thrusters.[79][80]

Specifications

Uncrewed version

The following specifications are published by SpaceX for the non-NASA, non-ISS commercial flights of the refurbished Dragon capsules, listed as "DragonLab" flights on the SpaceX manifest. The specifications for the NASA-contracted Dragon Cargo were not included in the 2009 DragonLab datasheet.[3]

- Pressure vessel

- 10 m3 (350 cu ft) interior pressurized, environmentally-controlled, payload volume.[3]

- Onboard environment: 10–46 °C (50–115 °F); relative humidity 25~75%; 13.9~14.9 psia air pressure (958.4~1027 hPa).[3]

- Unpressurized sensor bay (recoverable payload)

- 0.1 m3 (4 cu ft) unpressurized payload volume.

- Sensor bay hatch opens after orbital insertion to allow full sensor access to the space environment, and closes prior to reentry to Earth's atmosphere.[3]

- Unpressurized trunk (non-recoverable)

- 14 m3 (490 cu ft) payload volume in the 2.3 m (7 ft 7 in) trunk, aft of the pressure vessel heat shield, with optional trunk extension to 4.3 m (14 ft 1 in) total length, payload volume increases to 34 cubic metres (1,200 cu ft).[3]

- Supports sensors and space apertures up to 3.5 m (11 ft 6 in) in diameter.[3]

- Power, telemetry and command systems

- Power: twin solar panels providing 1,500 W average, 4,000 W peak, at 28 and 120 VDC.[3]

- Spacecraft communications: commercial standard RS-422 and military standard 1553 serial I/O, plus Ethernet communications for IP-addressable standard payload service.

- Command uplink: 300 kbps.[3]

- Telemetry/data downlink: 300 Mbit/s standard, fault-tolerant S-band telemetry and video transmitters.[3]

See also

- Comparable vehicles

- CST-100 – a spacecraft being developed by Boeing, in collaboration with Bigelow Aerospace

- Dream Chaser – a spaceplane being developed by Sierra Nevada Corporation

- Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle – a beyond-low-Earth-orbit spacecraft being developed by Lockheed Martin for NASA

- Blue Origin orbital spacecraft – a biconic nose cone design vehicle

- Reaction Engines Skylon – an unmanned British spaceplane currently under development

- Automated Transfer Vehicle – a single-use, expendable cargo vehicle currently in use by the ESA

- Cygnus spacecraft – a cargo vehicle under development by Orbital Sciences Corporation

- H-II Transfer Vehicle – an expendable cargo vehicle currently in use by JAXA

- Progress spacecraft – an expendable cargo vehicle currently in use by the Russian Federal Space Agency

References

- ^ "SPACEX WINS NASA COMPETITION TO REPLACE SPACE SHUTTLE" (Press release). Hawthorne, California: SpaceX. 8 September 2006. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ a b c "SpaceX Brochure – 2008" (PDF). Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Dragonlab datasheet" (PDF). Hawthorne, California: SpaceX. 8 September 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Bowersox, Ken (25 January 2011). "SpaceX Today" (PDF). SpaceX. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ Musk, Elon (17 July 2009). "COTS Status Update & Crew Capabilities" (PDF). SpaceX. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ a b Bates, Daniel (9 December 2010). "Mission accomplished! SpaceX Dragon becomes the first privately funded spaceship launched into orbit and guided back to Earth". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ a b "SpaceX's Dragon captured by ISS, preparing for historic berthing". NASASpaceflight.com. 25 May 2012.

- ^ a b c "SpaceX Launches Private Capsule on Historic Trip to Space Station". Space.com. 22 May 2012.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (25 May 2012). "Space X Capsule Docks at Space Station". New York Times. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "SpaceX's Dragon Docks With Space Station—A First". National Geographic. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ a b c "Worldwide Launch Schedule". Spaceflight Now Inc. 27 May 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Press Briefed On the Next Mission to the International Space Station". NASA. 20 March 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen (16 July 2010). "Second Falcon 9 rocket begins arriving at the Cape". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Dragon Overview". SpaceX. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ a b "SpaceX Updates — December 10, 2007". SpaceX. 10 December 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- ^ "Second Falcon 9 rocket begins arriving at the Cape". Spaceflight Now.

- ^ Jones, Thomas D. (2006). "Tech Watch — Resident Astronaut". Popular Mechanics. 183 (12): 31. ISSN 0032-4558.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "SpaceX • COTS Flight 1 Press Kit" (PDF). SpaceX. 6 December 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ "Dragon Drop Test – August 20, 2010". Spacex.com. 20 August 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Commercial Crew Development (CCDEV) video" (video). SpaceX. 14 January 2011. 3:40. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ "Elon Musk Congressional testimony October 26, 2011" (PDF).

- ^ "5 Fun Facts About Private Rocket Company SpaceX". Space.com. 21 May 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ Chow, Denise (8 December 2010). "Q & A with SpaceX CEO Elon Musk: Master of Private Space Dragons". Space.com. New York. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ a b Berger, Brian (8 March 2006). "SpaceX building reusable crew capsule". MSNBC. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "NASA selects crew, cargo launch partners". Spaceflight Now. 18 August 2006. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ Thorn, Valin (11 January 2007). "Commercial Crew & Cargo Program Overview" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ a b Boyle, Alan (18 August 2006). "SpaceX, Rocketplane win spaceship contest". MSNBC. New York. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ a b Berger, Brian (19 October 2007). "Time Runs out for RpK; New COTS Competition Starts Immediately". Space.com. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (19 February 2008). "Orbital beat a dozen competitors to win NASA COTS contract". NASA Spaceflight. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help) - ^ a b "F9/Dragon Will Replace the Cargo Transport Function of the Space Shuttle after 2010" (Press release). Hawthorne, California: SpaceX. 23 December 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ "SpaceX Manufactured Heat Shield Material Passes High Temperature Tests Simulating Reentry Heating Conditions of Dragon Spacecraft" (Press release). SpaceX. 23 February 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ Chaikin, Andrew (January 2012). "1 visionary + 3 launchers + 1,500 employees = ? : Is SpaceX changing the rocket equation?". Air & Space Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "UPDATE: Wednesday, September 23rd, 2009" (Press release). Hawthorne, California: SpaceX. 23 September 2009. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ Update on 23 September 2009 from SpaceX

- ^ a b Bergin, Chris (28 March 2010). "SpaceX announce successful activation of Dragon's CUCU onboard ISS". NasaSpaceflight (not affiliated with NASA). Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ "FORMER ASTRONAUT BOWERSOX JOINS SPACEX AS VICE PRESIDENT OF ASTRONAUT SAFETY AND MISSION ASSURANCE" (Press release). SpaceX. 18 June 2009. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- ^ Guy Norris (20 September 2009). "SpaceX, Orbital Explore Using Their Launch Vehicles To Carry Humans". Aviation Week.

- ^ "SpaceX Achieves Orbital Bullseye With Inaugural Flight of Falcon 9 Rocket: A major win for NASA's plan to use commercial rockets for astronaut transport". SpaceX. 7 June 2010.

- ^ "NASA Statements On FAA Granting Reentry License To SpaceX" (Press release). 22 November 2010.

- ^ "Private space capsule's maiden voyage ends with a splash". BBC News, 2010-12-08. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- ^ "STS-133: SpaceX's DragonEye set for late installation on Discovery". NASASpaceFlight.com. 19 July 2010.

- ^ Ray, Justin (9 December 2011). "SpaceX demo flights merged as launch date targeted". Tonbridge, Kent, United Kingdom: Spaceflight Now Inc. Archived from the original on 9 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ^ "ISS welcomes SpaceX Dragon". Wired, 25 May 2012.

- ^ "SpaceX's Dragon already achieving key milestones following Falcon 9 ride". NASASpaceflight.com. 22 May 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ "NASA ISS On-Orbit Status 22 May 2012". NASA via SpaceRef.com. 22 May 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ Pierrot Durand (28 May 2012). "Cargo Aboard Dragon Spacecraft to Be Unloaded On May 28". French Tribune.

- ^ a b "Splashdown for SpaceX Dragon spacecraft". BBC. 31 May 2012.

- ^ "SpaceX Dragon Capsule opens new era". Reuters via BusinessTech.co.za. 28 May 2012.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (12 April 2012). "ISS translates robotic assets in preparation to greet SpaceX's Dragon". NasaSpaceflight (not affiliated with NASA). Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ "SpaceX Dragon Air Circulation System" (PDF). SpaceX / American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "NASA Advisory Council Space Operations Committee" (PDF). NASA. 2010-07. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Commercial Orbital Transportation Services Overview" (PDF). NASA. 2012-04. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "SpaceX Launches Success with Falcon 9/Dragon Flight". NASA. 9 December 2010. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "SpaceX Launch Manifest". SpaceX. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (11 October 2010). "NASA expects a gap in commercial crew funding". Spaceflightnow. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ^ Chow, Denise (18 April 2011). "Private Spaceship Builders Split Nearly $270 Million in NASA Funds". Space.com. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ^ "Space Act Agreement No.NNK11MS04S between NASA and SpaceX for CCDev 2" (PDF). NASA. 18 April 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ a b Chow, Denise (18 April 2011). "Private Spaceship Builders Split Nearly $270 Million in NASA Funds". Space.com. New York. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ Paur, Jason (27 October 2011). "SpaceX Launch Abort System Receives Preliminary Approval". Wired. San Francisco. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ "CCDev 2 Milestone Schedule" (PDF). NASA. 16 February 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "ISS Update: SpaceX Space Act Agreement Status". NASA. 23 March 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "SpaceX Tests New ‘Super’ Rocket Engines". Wired, 1 February 2012.

- ^ NASA expects a gap in commercial crew funding, Spaceflightnow.com, 2010-10-11, accessed 2011-2-28.

- ^ "This Week in Space interview with Elon Musk". Spaceflight Now. 24 January 2010.

- ^ "Elon Musk's SpaceX presentation to the Augustine panel". YouTube. June, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Rosenberg, Zach (30 March 2012). "Boeing details bid to win NASA shuttle replacement". FlightGlobal. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ "COMMERCIAL CREW INTEGRATED CAPABILITY". NASA. 23 January 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ "Q+A: SpaceX Engineer Garrett Reisman on Building the World's Safest Spacecraft". PopSci. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

DragonRider, SpaceX's crew-capable variant of its Dragon capsule

- ^ "SpaceX Completes Key Milestone to Fly Astronauts to Internation Space Station". SpaceX. 20 October 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ Parma, George (20 March 2011). "Overview of the NASA Docking System and the International Docking System Standard" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

iLIDS was later renamed the NASA Docking System (NDS), and will be NASA's implementation of an IDSS compatible docking system for all future US vehicles

- ^ Bayt, Rob (26 July 2011). "Commercial Crew Program: Key Driving Requirements Walkthrough". NASA. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Oberg, Jim (28 March 2007). "Space station trip will push the envelope". MSNBC. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ With the exception of the Project Gemini spacecraft, which used twin ejection seats.

- ^ Spaceship teams seek more funding, msnbc.com, Cosmic Log, 2010-12-10, Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Taking the next step: Commercial Crew Development Round 2". SpaceX Updates webpage. SpaceX. 17 January 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ "In the news Paragon Space Development Corporation Joins SpaceX Commercial Crew Development Team". Paragon Space Development Corporation. 16 June 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ "SpaceX scrubs launch to ISS over rocket engine problem". Deccan Chronicle. 19 May 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ "Launch Manifest". Hawthorne, California: SpaceX. 2011. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ^ a b c Wall, Mike (31 July 2011). "'Red Dragon' Mission Mulled as Cheap Search for Mars Life". SPACE.com. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ a b c "NASA ADVISORY COUNCIL (NAC) – Science Committee Report" (PDF). Ames Research Center, NASA. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2012.